ETHJ Vol-39 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor David Ake, University of Miami Associate Professor Stephen Berrey Associate Professor Christi-Anne Castro Associate Professor Mark Clague © Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik 2016 DEDICATION To Jarvis P. Chuckles, an amalgamation of all those who made this project possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation was made possible by fellowship support conferred by the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School and the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, as well as ample teaching opportunities provided by the Musicology Department and the Residential College. I am also grateful to my department, Rackham, the Institute, and the UM Sweetland Writing Center for supporting my work through various travel, research, and writing grants. This additional support financed much of the archival research for this project, provided for several national and international conference presentations, and allowed me to participate in the 2015 Rackham/Sweetland Writing Center Summer Dissertation Writing Institute. I also remain indebted to all those who helped me reach this point, including my supervisors at the Hatcher Graduate Library, the Music Library, the Children’s Center, and the Music of the United States of America Critical Edition Series. I thank them for their patience, assistance, and support at a critical moment in my graduate career. This project could not have been completed without the assistance of Bruce Boyd Raeburn and his staff at Tulane University’s William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive of New Orleans Jazz, and the staff of the Historic New Orleans Collection. -

Neal Thesis FINAL

GUARDING SPACE AND PLACE: ELITE AND KLAN COUNTERBALANCE COMMUNITIES IN JAZZ AGE DALLAS by Lauren Elizabeth Neal, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in History May 2015 Committee Members: Rebecca Montgomery, Chair Jeffrey Helgeson Jessica Pliley COPYRIGHT by Lauren Elizabeth Neal 2015 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Lauren Elizabeth Neal, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author deeply thanks her thesis committee and the wonderful faculty in the History Department. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER I. PROLOGUE ........................................................................................................ 1 II. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. -

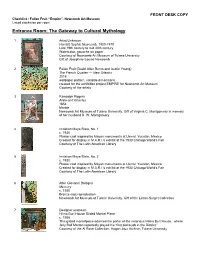

Checklist by Room

FRONT DESK COPY Checklist - Fallen Fruit “Empire”, NewcomB Art Museum Listed clockwise per room Entrance Room: The Gateway to Cultural Mythology 1 Artist Unknown Harriott Sophie Newcomb, 1855-1870 Late 19th century to mid 20th century Watercolor, gouache on paper Courtesy of Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University Gift of Josephine Louise Newcomb 2 Fallen Fruit (David Allen Burns and Austin Young) The French Quarter — New Orleans 2018 wallpaper pattern, variable dimensions created for the exhibition project EMPIRE for Newcomb Art Museum Courtesy of the artists 3 Randolph Rogers Atala and Chactas 1854 Marble Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of Virginia C. Montgomery in memory of her husband R. W. Montgomery 4 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 1 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 5 Imitation Maya Stela, No. 2 c. 1930 Plaster cast inspired by Mayan monuments at Uxmal, Yucatan, Mexico Created for display in M.A.R.I.'s exhibit at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair Courtesy of The Latin American Library 6 After Giovanni Bologna Mercury c. 1580 Bronze cast reproduction Newcomb Art Museum of Tulane University, Gift of the Linton-Surget Collection 7 Designer unknown Hilma Burt House Gilded Mantel Piece c. 1906 This gilded mantelpiece adorned the parlor of the notorious Hilma Burt House, where Jelly Roll Morton reportedly played his “first piano job in the District.” Courtesy of the Al Rose Collection, Hogan Jazz Archive, Tulane University 8 Casting by the Middle American Research Institute Cast inspired by architecture of the Governor’s Place of Uxmal, Yucatán, México c.1932 Plaster, created for A Century oF Progress Exposition (also known as The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933), M.A.R.I. -

Performance Shows Complexity of Life in Storyville's Mahogany Hall

Tulane University Performance shows complexity of life in Storyville’s Mahogany Hall October 01, 2018 3:00 PM Miriam Taylor [email protected] Actors Valentine Pierce, left, and Jasmine Davis, are part of the "Postcards from Over the Edge" cast. (Image by CFreedom) Newcomb Art Museum will host the world premiere of Postcards From Over the Edge, a new theatrical work that illustrates the historical struggles related to the sale of sex in Louisiana. Developed collaboratively by five New Orleans–based artists, the play explores New Orleans’ complex relationship with prostitution and is a local project of the National Performance Network. The performance shifts between the Storyville Mahogany Hall era, circa 1890, a time when prostitution was legal, and the actions of the modern-day civil rights movement. Development of Postcards From Over the Edge was initiated by Karel Sloane-Boekbinder, an award-winning multidisciplinary artist and programs assistant in the School of Liberal Arts’ Department of Theatre and Dance. “Because I’m an artist, my first thought was, how do I tell stories that are not being told, how do I share these stories with a larger community, and how do I connect the community together,” said Sloane-Boekbinder. “We think it’s magical that we have the opportunity to perform in a space that has pieces from Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall on display.” Tulane University | New Orleans | 504-865-5210 | [email protected] Tulane University The items once owned by madame Lulu White, proprietor of Storyville’s Mahogany Hall brothel, that are on display as part of the Newcomb Art Museum’s EMPIRE exhibit include salvaged wallpaper, The New Mahogany Hall souvenir booklet, and her desk. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 40 Issue 2 Article 15 10-2002 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (2002) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 40 : Iss. 2 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol40/iss2/15 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATlON 69 BOOK REVIEWS Max's Memoirs, Max S. Lale (Eakin Press~ P.O. Box 90159, Austin, TX 78709 0159) 2001. Contents. Foreword. Afterword. B&W Photos. P. 236. $24.95. Paperback. Max Lale has spent much of his eighty-four years writing for newspapers, in learned journals~ at the behest of civic or historical organizations, and at least four books. However, when he began writing the manuscript that became Max's Memoirs, he thought he was writing for himself or at most for his family and a few close friends. Two of those friends, journalist Bill Moyers and Stephen F. Austin history professor Archie McDonald, convinced him the material needed to be published. They were right. The manuscript was composed, chapter by chapter, on Lale's beloved Royal manual typewriter - graciously offered to the news staff of his former employer, the Marshall News Messenger, during what turned out to be the non-crisis Y2K crisis. -

1848, European Revolutions Of, 14, 137 Beginnings Of, 94 And

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87564-6 - The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828-1861 Yonatan Eyal Index More information Index 1848, European revolutions of, 14, Allen, William, 13, 84–6, 89, 103, 110, 137 144, 234 beginnings of, 94 on the 1846 rivers and harbors bill, 61 and coinage of the phrase Young as ally of Marcus Morton, 197 America, 6 as Chairman of Senate Foreign and Democratic views on race and Relations Committee, 8 immigration, 162 and Cumberland Road, 44 failure of, 104, 107 and Greenbacks, 85–6 and George Law, 87 instructions from constituents to, 51, and Margaret Fuller, 100 55, 56 related to Cuba movement, 135 and internal improvements funding, related to New Democratic economic 50 outlook, 65, 68 later career of, 8 relevance to the American situation, as lifelong Democrat, 200 102 and monopolies, 77 role in party competition, 67 and Monroe Doctrine, 120 socioeconomic aspects of, 106 as Ohio governor, 7 Young American interest in, 94 and Oregon crisis, 121–7 Abolitionism, 185, 196 pro-French resolution of, 103 and Arthur and Lewis Tappan, 183 views of commerce, 40 and context of northern reform, 145 views of slavery, 192 and John L. O’Sullivan, 75, 198–99 voted out of the Senate, 231 relationship to Democratic Party, as western representative, 124 184 American Anti-Slavery Society, 26, 185 Adams, Charles Francis, Sr., 186, 207 American Colonization Society, 26, 34, Adams, John, 17, 21, 31 190, 192–3 Adams, John Quincy, 18, 23 American System, 18, 23, 71, 176, 218 Agassiz, -

Copyright 2015 Jasmine Danielle Parker

Copyright 2015 Jasmine Danielle Parker (DE)SEGREGATION IN POST-BROWN DALLAS, TEXAS: A HISTORICAL NARRATIVE ATTRIBUTING THE RESPONSE AND SOCIAL ACTIVISM EFFORTS OF AFRICAN AMERICAN DALLASITES, 1950s-1970s BY JASMINE DANIELLE PARKER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education Policy, Organization & Leadership with a concentration in Educational Administration and Leadership in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christopher M. Span, Chair Professor James D. Anderson Associate Professor Menah Pratt-Clarke, Esq. Associate Professor Yoon K. Pak Assistant Professor Lorenzo Baber ii ABSTRACT This study examines the role appointed desegregation committees had on the evolution of the public schooling experience in Dallas, Texas during the mid-twentieth century. It has a twofold purpose dating back to the eras commonly referred to as Plessy and Brown, respectively. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States presented to the world its reasoning in the case of Brown v. Board of Education. The Court declared legally segregated public schooling facilities unconstitutional. However, this original decision of the Court failed to enunciate how and when school districts were to end segregated schooling. In a later decision, known as Brown II, the organizational strategies and implementation responsibilities in desegregation plans were designated the responsibility of city leadership, school boards, and local courts of law. Resultantly, this investigation seeks to address the relationship between local culture, civic leaders, and federal requirements, specifically their influence and contribution, as it relates to the legal journey of creating institutionally desegregated facilities. -

Cover Page the Handle Holds

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/85166 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Mareite T.J.F. Title: Conditional freedom : free soil and fugitive slaves from the US South to Mexico's Northeast, 1803-1861 Issue Date: 2020-02-13 PART 2 * * * CRAFTING FREEDOM III Self-Liberated Slaves and Asylum in Northeastern Mexico, 1803-1836 Introduction During one of his several trips to Mexican Texas to promote black emigration from the US to Mexico, abolitionist Benjamin Lundy arrived at San Antonio de Bexar in August 1833 and recognized a “free black man” named Mathieu Thomas, whom he had met the previous summer in Nacogdoches. According to Lundy, the man was originally from North Carolina and had been brought to the region as a slave by his owner in the 1820s, but had been subsequently manumitted. Now employed as a blacksmith in Bexar, he appeared to be doing well for himself and he enthusiastically asserted that “the Mexicans pay him the same respect as to other laboring people”, regardless of the color of his skin. What Lundy was apparently not aware of was that Mathieu Thomas was in fact not a free black man at all, but rather a fugitive from slavery.1 His apparent success in Mexico (which neatly fit with Lundy’s goal of presenting Mexico as a racial haven), moreover, obscured a series of fierce struggles the blacksmith had had to overcome in order to secure his own freedom in the years before the Texas Revolution, as we will see. Countless fugitive slaves settled in the Mexican Northeast prior to Texan independence in 1836. -

The Second Seminole War, the Ad Hoc Origins of American Imperialism, and the Silence of Slavery

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 This Inglorious War: The econdS Seminole War, the Ad Hoc Origins of American Imperialism, and the Silence of Slavery Daniel Scallet Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Scallet, Daniel, "This Inglorious War: The eS cond Seminole War, the Ad Hoc Origins of American Imperialism, and the Silence of Slavery" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 638. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/638 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University in St. Louis Department of History Dissertation Examination Committee: Iver Bernstein, Chair Elizabeth Borgwardt Randall Calvert Wayne Fields Peter Kastor David Konig "This Inglorious War": The Second Seminole War, the Ad Hoc Origins of American Imperialism, and the Silence of Slavery by Daniel Scallet A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri Copyright by Daniel Scallet 2011 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Dwight D. Eisenhower Institute whose Clifford Roberts Fellowship Program provided funding for this project. I have also benefitted greatly from the Lynne Cooper Harvey Fellowship in American Culture Studies. Finally, I would like to thank the faculty at Washington University from whom I have learned so much as well as friends and family to whom I am eternally grateful. -

Failing the Race: a Historical Assessment of New Orleans Mayor

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Failing the race: a historical assessment of New Orleans Mayor Sidney Barthelemy, 1986-1994 Lyle Kenneth Perkins Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Perkins, Lyle Kenneth, "Failing the race: a historical assessment of New Orleans Mayor Sidney Barthelemy, 1986-1994" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 834. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/834 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAILING THE RACE: A HISTORICAL ASSESSMENT OF NEW ORLEANS MAYOR SIDNEY BARTHELEMY, 1986-1994 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Lyle Kenneth Perkins B.A., Armstrong Atlantic State University, 2002 August 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have incurred numerous debts in the writing of this thesis. Louisiana State University’s Huel D. Perkins Doctoral Fellowship has sustained my scholarship. Leonard Moore provided excellent direction and encouragement. Wayne Parent encouraged me to step out of my comfort zone and chart a new course. Tiwanna Simpson has been an indispensable friend and mentor. My earliest teachers, Maurice and Betty Perkins, continue to provide me with new insights and encouragement. -

California State University, Northridge the Language

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE THE LANGUAGE OF MANIFEST DESTINY: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF AMERICAN TRAVELER ACCOUNTS TO CUBA, 1820-1859 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in History By Matthew M. Vacca December 2012 The thesis of Matthew M. Vacca is approved: Dr. Susan Fitzpatrick-Behrens, Ph.D. Date Dr. Thomas Devine, Ph.D. Date Dr. Patricia Juarez-Dappe, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Acknowledgements I should like to offer my deep and sincere appreciation to my director, Dr. Patricia Juarez-Dappe, for her patient guidance, wisdom, and positive encouragement throughout this process. I must also recognize my other two readers for their help and consideration. To Dr. Susan Fitzpatrick-Behrens, you have taught me to value the voices of all people, not just the loudest. To Dr. Thomas Devine, words cannot express the transformative difference your mentorship has made in my life. I would also like to offer a special acknowledgement to Dr. Merry Ovnick, who gave me confidence in the classroom. Thank you, all, for inspiring me to be an earnest student and better teacher. This is also my opportunity to offer my unyielding appreciation to my parents, who instilled in me the idea that education matters—even though it is sometimes wasted on the young. Of course I cannot forget Kim, Jake, and Babu. Your collective support, stability, and laughter make life joyous and precious. Thank you for never giving up on me. I love you all as high as the sky, and as deep as the ocean. -

Part II M. Empires and the American Imagination, C. 1763- C.1900

Greetings, prospective Special Subject students for 2020-21! This file contains the (sprawling) reading list for 2018-19, the last year in which this Special was taught. There may be a few tweaks to particular topics for next year, and I strongly suspect I will cut back on some of the required reading (especially in the later weeks) to help you focus your reading on a slightly shorter range of primary sources. But this list should give you a good idea of the topics you’ll be engaging if you take ‘Empires and the American Imagination’. Happy choosing! Nick Guyatt March 2020 Update May 2020 We still don’t know how the Covid crisis will affect teaching arrangements in 2020-21, but students should be assured that we’ll adapt this Special Subject quickly and creatively to any challenges and constraints we may face. This may include new ways of interacting in addition to the usual seminar slot, including mini-lectures and a variety of group tasks which will keep everyone informed and engaged beyond our weekly meetings. 1 Empires and the American imagination, c.1763 – c.1900 Nicholas Guyatt For decades, American historians have argued about whether the United States should be considered an empire, or about when its transition to imperial status took place. Much less attention has been paid to how Americans themselves understood and encountered imperialism, especially during the high-water mark of European empires in the nineteenth century. This course invites students to examine imperialism through the observations and engagements of Americans both at home and overseas.