World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HACCP in AQUAFARMS a Practical Handbook

HACCP in AQUAFARMS A practical handbook S. Regidor & L. Dabbadie (eds) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Centre de Coopération Internationale en Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) Building Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement. Elliptical Road, Diliman Avenue Agropolis, 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5 Quezon City, Philippines France 1 This handbook is the result of a collective work that involved many actors, including: Simeona Regidor Remedios Ongtangco Rosa Macas Ligaya Cabrera Joselito Lacap Joe Balthazar Jean-Michel Otero J. Lorenzo Vergara Pascal Levy Nestor Natanauan Josie dela Vega Nenita Kawit Maurita Rosana Jorge Tabilog Gregorio Biscocho Mario Balazon Sonia Somga Carmen Augustine Nuttawat Suchart Marcelino Ortiz Gonzalo Coloma Amor Diaz Lilia Pelayo Lionel Dabbadie 2 INTRODUCTION “If it’s good for me, then it’s good for them” —Pampanga Shrimp Farmer, March 2009 HACCP1 has become a basic requirement for international trade, not only for Filipinos wishing to export to most countries, but also for foreign operators wanting to sell their products on the Philippine market. It is important to understand the roots of the success of HACCP, because it is not just a constraint to be complied with. If well understood, HACCP is an opportunity for Filipino farmers to take the lead in the highly competitive context of the 21st century’s global economy. With the globalization of trade, the geographical and cultural gaps between food producers and food consumers have never been larger. Filipinos eat imported rice and Europeans eat imported shrimps. But the growing distance between producing and consuming areas is also a factor that breeds misunderstanding and sometimes distrust, whether justified or not. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 10.5.2017 SWD(2017) 160

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 10.5.2017 SWD(2017) 160 final PART 61/62 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Europe's Digital Progress Report 2017 EN EN Europe’s Digital Progress Report-2017 Telecom chapter SWEDEN 1. Competitive environment Coverage SE-2015 SE-2016 EU-2016 Fixed broadband coverage (total) 99% 99% 98% Fixed broadband coverage (rural) 94% 91% 93% Fixed NGA coverage (total) 76% 79% 76% Fixed NGA coverage (rural) 14% 22% 40% 4G coverage (average of operators) no data 100% 84% Source: Broadband Coverage Study (IHS and Point Topic). Data as of October 2015 and October 2016 Fixed broadband market The Swedish broadband market is characterised by rapidly growing consumer demand for ultrafast broadband and a corresponding rapidly declining consumer demand for slower broadband. On the fixed broadband market, fibre subscriptions continued to increase over the reporting period (+17% of fibre LAN compared to 2015). The Swedish broadband market also featured a slight increase (+4%) in cable TV subscriptions and conversely a substantial decrease in xDSL subscriptions (-10%)1. Sweden is currently among the EU countries with a very advanced fixed broadband coverage baseline. Currently, Sweden scores well above the EU average for overall 4G coverage (100% against 84% for the EU) but lags behind the EU average for fixed next-generation access (NGA) coverage in rural areas (21% against 40% for the EU). The role of municipalities in providing local fibre is remarkable in Sweden. The fibre market is fragmented, with approximately 180 local fibre networks complementing the offer of the incumbent and the cable sector. Municipalities’ networks offer their services via what are called communication operators operating the network of the dark fibre owner. -

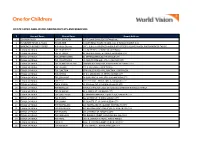

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

Annual Licence Fees for 900 Mhz and 1800 Mhz Spectrum Statement

Annual licence fees for 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum Statement Annexes 9-13 Annual licence fees for 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum Contents 9 Technical and commercial evidence 3 10 Annualisation: supporting material 40 11 Marginal bidder analysis of paired 2.6 GHz spectrum in the absence of Niche 66 12 Statutory instrument 68 13 Glossary of terms 72 Annual licence fees for 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum Annex 9 9 Technical and commercial evidence Introduction A9.1 This annex contains further material on technical and commercial evidence which supports our assessment in Sections 1 and 2 on future spectrum availability and in Section 3 on estimating lump-sum values. It covers: a) Possibility of greater certainty around spectrum availability; b) Technical and commercial evidence relating to the relative values of 800 MHz and 900 MHz spectrum; c) Technical and commercial evidence relating to the value of 1800 MHz spectrum; d) Network cost modelling; and e) Qualcomm’s trade of licences for 1.4 GHz spectrum. A9.2 We outlined our provisional views on the first and fourth of these issues in Annex 9 of our August 2014 consultation, and on the third issue in Annex 7 of the August 2014 consultation.1 Stakeholders provided a numbers of comments on these views. Additionally, H3G and Vodafone made arguments relating to the second issue of the technical and commercial value of 900 MHz spectrum relative to 800 MHz. We considered these comments as part of our assessment of technical and commercial evidence in Annex 9 of our February 2015 consultation. -

Creating the Technology to Connect the World

Nokia in 2018 Creating the technology to connect the world Contents Business overview 02 We create the technology to connect the world 02 Letter from our President and CEO 04 Market trends driving our strategy 06 Our strategy 08 Networks business 10 Mobile Networks 12 Fixed Networks 14 Global Services 16 IP/Optical Networks 18 Nokia Software 20 Nokia Enterprise 22 Nokia Technologies 24 Nokia Bell Labs 26 Principal industry trends affecting operations 28 Board review 32 Board review 34 Results of operations 35 Results of segments 40 Liquidity and capital resources 47 Significant subsequent events 49 Sustainability and corporate responsibility 50 Shares and share capital 58 Risk factors 60 Corporate governance 62 Corporate governance statement 64 Compensation 82 General facts on Nokia 98 Our history 100 Memorandum and Articles of Association 101 Selected financial data 103 Shares 104 Shareholders 107 Production of infrastructure equipment and products 108 Financial statements 109 Consolidated primary statements 110 Notes to consolidated financial statements 116 Parent company primary statements 184 Notes to the parent company primary statements 188 Signing of the Annual Accounts 2018 202 Auditor’s report 203 Other information 207 Foward-looking statements 208 Use of certain terms 209 Key ratios 207 Alternative performance measures 211 Glossary of terms 212 Investor information 215 Contact information 216 01 We create the technology to connect the world We are at the dawn of a new era. Digital A global technology leader technologies – cloud computing, artificial intelligence, machine learning, the Internet Net sales 2018 by region of Things and 5G networks – are changing our world. -

Creating the Technology to Connect the World

Nokia in 2019 Creating the technology to connect the world Nokia in 2019 Nokia in 2019 This is it. 5G is here. Networks, businesses and public services are being transformed and we are at the forefront. Rajeev Suri President and CEO Business overview 04 We create the technology to connect the world 04 Letter from our President and CEO 06 Market trends driving our strategy 10 Our strategy 12 Innovation 17 Nokia Bell Labs 19 Sales and marketing 21 Business groups 22 Mobile Networks 22 Global Services 24 Fixed Networks 26 IP/Optical Networks 28 Nokia Software 30 Nokia Enterprise 32 Nokia Technologies 36 Principal industry trends affecting operations 40 Board review 44 Board review 46 Results of operations 47 Results of segments 53 Liquidity and capital resources 61 Significant subsequent events 63 Sustainability and corporate responsibility 64 Shares and share capital 71 Risk factors 72 Corporate governance 74 Corporate governance statement 78 Compensation 97 General facts on Nokia 110 Our history 112 Memorandum and Articles of Association 113 Selected financial data 115 Shares 116 Shareholders 118 Production of infrastructure equipment and products 120 Financial statements 121 Consolidated primary statements 122 Notes to consolidated financial statements 128 Parent company primary statements 195 Notes to the parent company primary statements 199 Signing of the Annual Accounts 2019 213 Auditor’s report 214 Other information 219 Forward-looking statements 220 Introduction and use of certain terms 221 Key ratios 222 Alternative performance measures 223 Glossary of terms 224 Investor information 227 Contact information 228 NOKIA IN 2019 01 02 NOKIA IN 2019 Connecting people across communities and industries wherever they live and work. -

Western Europe

LTE‐ LTE‐ Region Country Operator LTE Advanced 5G Advanced Pro Western Europe 88 69 1 18 Andorra Total 10 0 0 Andorra Andorra Telecom 10 0 0 Austria Total 33 0 1 Austria A1 Telekom Austria 11 0 0 Austria Hutchison Drei Austria 11 0 1 Austria T‐Mobile Austria (Magenta Telekom) 11 0 0 Belgium Total 33 0 0 Belgium Orange Belgium 11 0 0 Belgium Proximus 11 0 0 Belgium Telenet (incl. BASE) 11 0 0 Denmark Total 54 0 0 Denmark Hi3G Access (3) 11 0 0 Denmark Net 1 Denmark 10 0 0 Denmark TDC (YouSee) 11 0 0 Denmark Telenor Denmark 11 0 0 Denmark Telia Denmark 11 0 0 Finland Total 53 0 2 Finland Aland Telecommunications (Alcom) 10 0 0 Finland DNA Finland 11 0 0 Finland Elisa Corporation 11 0 1 Finland Telia Finland (formerly Sonera) 11 0 1 Finland Ukkoverkot (Ukko Mobile) 10 0 0 France Total 44 0 0 France Altice France (SFR) 11 0 0 France Bouygues Telecom 11 0 0 France Free Mobile (Iliad) 11 0 0 France Orange France 11 0 0 Germany Total 33 0 2 Germany Telefonica Deutschland Holding 11 0 0 Germany Telekom Deutschland 11 0 1 Germany Vodafone Germany 11 0 1 Greece Total 33 0 0 Greece Cosmote 11 0 0 Greece Vodafone Greece (incl. Hellas Online) 11 0 0 Greece Wind Hellas (incl. Tellas) 11 0 0 Greenland Total 10 0 0 Greenland TELE Greenland 10 0 0 Guernsey Total 32 0 0 Guernsey Airtel Limited (Airtel‐ Guernsey Vodafone) 10 0 0 Guernsey JT Guernsey (formerly Wave Telecom) 11 0 0 Sure Guernsey (formerly Guernsey Guernsey Telecom) 11 0 0 Iceland Total 33 0 0 Iceland Nova (Iceland) 11 0 0 Iceland Siminn (Iceland Telecom) 11 0 0 Iceland Vodafone Iceland (Syn) -

Telia Company Interim Report January-June 2017

TELIA COMPANY INTERIM REPORT JANUARY-JUNE 2017 Q2 Telia Company Interim Report January–June 2017 Q2 CASH FLOW EXECUTION AND COST SIDE ADDRESSED Second quarter summary • As earlier announced former segment region Eurasia is reported as held for sale and discontinued operations. • Net sales in local currencies, excluding acquisitions and disposals, fell 0.4 percent. In reported currency, net sales fell 6.3 percent to SEK 19,801 million (21,130). Service revenues in local currencies, excluding acquisitions and disposals, fell 0.6 percent. • Adjusted EBITDA declined 3.3 percent in local currencies, excluding acquisitions and disposals. In reported cur- rency, adjusted EBITDA, fell 4.6 percent to SEK 6,095 million (6,389). The adjusted EBITDA margin improved to 30.8 percent (30.2). • Adjusted operating income declined 16.7 percent to SEK 3,702 million (4,446). • Total net income attributable to the owners of the parent fell to SEK -397 million (1,439) and earnings per share to SEK -0.09 (0.33). Total net income fell to SEK -308 million (3,902). • Free cash flow, in continuing and discontinued operations, improved to SEK 2,772 million (1,698). • The operational free cash flow outlook for 2017 is improved from above SEK 7.0 billion to above SEK 7.5 billion. First half summary • Net sales in local currencies, excluding acquisitions and disposals, increased 1.2 percent. In reported currency, net sales fell 6.0 percent to SEK 39,053 million (41,524). Service revenues in local currencies, excluding acquisi- tions and disposals, increased 0.4 percent. -

ITU Normal.Dot

Bulletin d'exploitation de l'UIT www.itu.int/itu-t/bulletin No 1109 1.X.2016 (Renseignements reçus au 16 septembre 2016) ISSN 1564-524X (En ligne) Place des Nations CH-1211 Bureau de la normalisation des télécommunications (TSB) Bureau des radiocommunications (BR) Genève 20 (Suisse) Tél: +41 22 730 5211 Tél: +41 22 730 5560 Tél: +41 22 730 5111 Fax: +41 22 730 5853 Fax: +41 22 730 5785 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Table des matières Page Information générale Listes annexées au Bulletin d'exploitation de l'UIT: Note du TSB .................................................................. 3 Approbation de Recommandations UIT-T ..................................................................................................... 4 Service téléphonique: Chili (Subsecretaría de Telecomunicaciones, Santiago du Chili) ............................................................... 4 Danemark (Danish Energy Agency, Copenhague) .................................................................................... 4 Changements dans les Administrations/ER et autres entités ou Organisations: Mongolie (Information Technology, Post and Telecommunications Authority (ITPTA), Ulaanbaatar): Changement de nom ........................................................................................................................... 5 Singapour (InfoComm Development Authority of Singapore (IDA), Singapore): Changement de nom ... 5 Restrictions de service .................................................................................................................................. -

PORT of MANILA - Bls with No Entries As of July 6, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of July 5, 2021

PORT OF MANILA - BLs with No Entries as of July 6, 2021 Actual Cargo Arrival Date of July 5, 2021 ACTUAL DATE ACTUAL DATE OF No. CONSIGNEE/NOTIFY PARTY CONSIGNEE ADDRESS REGNUM BL DESCRIPTION OF ARRIVAL DISCHARGED RM 316 PETERSON BLDG 352 T PINPIN STREET COR ESCOLTA STREET 1X40 CNTR STC 650 CTNS SOLAR PANEL HS CODE 1 5B DYNASTY TRADING 7/5/2021 7/5/2021 HUE0014-21 KINS415021 BRGY 8541 40 291 ZONE 027 BINONDO MANILA 1006 306 ARMAGARITA BLDG. 28 MATALINO ST. QUEZON CITY 01X40SH CONTAINING 01 UNIT WITH: 1 BRAND 2 A M LEYCO AUTO TRADING 1100 PHILIPPINES CONTACT 7/5/2021 7/5/2021 EGP0022-21 EGLV703180522778 NEW VEHICLE HT CODE:870324 VIN: 94292 A.M. LEYCO TRADING TEL 639273992122 TRADING STC 25 PALLETS NEW CLEANWELL STYLE 2F TWIN DIAMOND BLDG LOT YELLOW DUST MASK MASK AIR QUEEN (TOPTEC) AD INTERNATIONAL 6268 3 7/5/2021 7/5/2021 HUE0014-21 LAIXBSMN2106128 MASK AIR QUEEN (TOPTEC) AIRBON IL WOUL (KF CONSUMER GOODS MABINI ST POB II ALFONSO 94) GOOD MANNER YELLOW DUST MASK GOOD CAVITE MANNER YELLOW DUST 4123 PHILS ALEJO SANTOS RD. PUROK CAMIA SAN J OSE PLARIDEL FENCE H.S. CODE 9506.99 SAW FRAME H.S. CODE ADMIRAL HARDWARE BULACAN PHILIPPINES TI N NO. 4 7/5/2021 7/5/2021 SIC0048-21 SITGNBMS234615 8202.10 KITCHENWARE EGG BEATER H.S. CODE TRADING 0120E GOV 767 613 785 000 TEL NO 632 7323.99 8404 02 72 EMAIL ADDRESS CHUAALYS SALES INC 706 7TH AVE BET 2 PALLETS STC TURBOCHARGER SERVICE CHRA ADVANCE DIESEL SYSTEM 5 4TH AND 5TH ST MM PH 1403 7/5/2021 7/5/2021 HUE0014-21 YCHKMNL21060001 AND OTHER PARTS HS CODE 7326 90 INVOICE NO AND TURBO CALOOCAN CITY 990123294 990123295 990123296 40 PALLET PAPER HT CODE:480255 AS PER ADVANCE PAPER 6 7/5/2021 7/5/2021 EGP0022-21 EGLV080100313521 PROFORMA INVOICE NO. -

Europe 173 82 Albania Total 30 Albania Albtelecom 10 ONE Telecommunications (Formerly Telekom Albania Albania) 10 Albania Vodafone Albania (Incl

Region Country Operator LTE 5G Europe 173 82 Albania Total 30 Albania ALBtelecom 10 ONE Telecommunications (formerly Telekom Albania Albania) 10 Albania Vodafone Albania (incl. ABCom) 10 Andorra Total 10 Andorra Andorra Telecom 10 Austria Total 33 Austria A1 Telekom Austria 11 Austria Hutchison Drei Austria 11 Austria T‐Mobile Austria (Magenta Telekom) 11 Belarus Total 41 Belarus A1 Belarus 11 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 10 Belarusian Telecommunications Network (BeST, Belarus life:)) 10 Belarus MTS Belarus 10 Belgium Total 31 Belgium Orange Belgium 10 Belgium Proximus 11 Belgium Telenet (incl. BASE) 10 Bosnia‐Herzegovina Total 30 Bosnia‐Herzegovina BH Telecom 10 Bosnia‐Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 10 Bosnia‐Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 10 Bulgaria Total 52 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 11 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 10 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 10 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 10 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 11 Croatia Total 31 Croatia A1 Hrvatska (formerly VIPnet/B.net) 10 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 11 Croatia Telemach Hrvatska (formerly Tele2) 10 Cyprus Total 31 Cyprus Cytamobile‐Vodafone 11 Cyprus Epic (previously MTN Cyprus) 10 Cyprus PrimeTel (Cyprus) 10 Czech Republic Total 43 Czech Republic Nordic Telecom 10 Czech Republic O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 11 Czech Republic T‐Mobile Czech Republic 11 Czech Republic Vodafone Czech Republic 11 Denmark Total 54 Denmark Hi3G Access (3) 11 Denmark Net 1 Denmark 10 Denmark TDC (incl. Nuuday, TDC Net) 11 Denmark Telenor Denmark 11 Denmark Telia Denmark 11 Estonia Total 31 -

Telia Company Interim Report January-March 2017

TELIA COMPANY INTERIM REPORT JANUARY-MARCH 2017 Q1 Telia Company Interim Report January–March 2017 Q1 REVENUE AND CASH FLOW GROWTH First quarter summary • As earlier announced former segment region Eurasia is reported as held for sale and discontinued operations. Sergel is reported as held for sale. • Net sales in local currencies, excluding acquisitions and disposals, increased 3.0 percent. In reported currency, net sales fell 5.6 percent to SEK 19,252 million (20,394). Service revenues in local currencies, excluding acquisi- tions and disposals, increased 1.4 percent. • EBITDA, excluding non-recurring items, declined 0.9 percent in local currencies, excluding acquisitions and dis- posals. In reported currency, EBITDA, excluding non-recurring items, declined 1.1 percent to SEK 6,149 million (6,217). The EBITDA margin, excluding non-recurring items, rose to 31.9 percent (30.5). • Operating income, excluding non-recurring items, declined 9.4 percent to SEK 3,805 million (4,198) mainly due to lower contribution from associated companies. • Total net income attributable to the owners of the parent increased to SEK 6,984 million (3,766) and earnings per share to SEK 1.61 (0.87). Total net income increased to SEK 7,143 million (3,911). The provision for settlement amount proposed by the US and Dutch authorities has been adjusted to USD 1.0 billion (SEK 8.9 billion) from USD 1.45 billion (SEK 13.2 billion) per December 31, 2016. The total net income effect in the first quarter 2017 of the change in the provision, foreign exchange differences and the hedge was SEK 4.1 billion.