Analysys Mason Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITC Operational Procedures for Issuing Frequency Assignments and Radio Licenses for Professional Radiocommunication Services

CITC Operational Procedures for Issuing Frequency Assignments and Radio Licenses for Professional Radiocommunication Services Contents 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 5 2. AERONAUTICAL SERVICES ................................................................................. 6 2.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 6 2.2 DESCRIPTION OF SERVICES/LICENCES ................................................................ 6 2.2.1 LICENCES AVAILABLE. ........................................................................................ 6 2.2.2 WHO CAN APPLY ................................................................................................ 7 2.3 FREQUENCY BANDS ........................................................................................... 7 2.4 LICENSING GUIDELINES ...................................................................................... 7 2.4.1 CALL SIGNS ....................................................................................................... 7 2.4.2 FITTING OF EQUIPMENT ...................................................................................... 8 2.4.3 OPERATION OF EQUIPMENT ................................................................................ 8 2.5 LICENCE APPLICATION FORMS ............................................................................ 8 2.6 TIMESCALES FOR LICENCE ISSUE ....................................................................... -

HACCP in AQUAFARMS a Practical Handbook

HACCP in AQUAFARMS A practical handbook S. Regidor & L. Dabbadie (eds) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Centre de Coopération Internationale en Philippine Coconut Authority (PCA) Building Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement. Elliptical Road, Diliman Avenue Agropolis, 34398 Montpellier Cedex 5 Quezon City, Philippines France 1 This handbook is the result of a collective work that involved many actors, including: Simeona Regidor Remedios Ongtangco Rosa Macas Ligaya Cabrera Joselito Lacap Joe Balthazar Jean-Michel Otero J. Lorenzo Vergara Pascal Levy Nestor Natanauan Josie dela Vega Nenita Kawit Maurita Rosana Jorge Tabilog Gregorio Biscocho Mario Balazon Sonia Somga Carmen Augustine Nuttawat Suchart Marcelino Ortiz Gonzalo Coloma Amor Diaz Lilia Pelayo Lionel Dabbadie 2 INTRODUCTION “If it’s good for me, then it’s good for them” —Pampanga Shrimp Farmer, March 2009 HACCP1 has become a basic requirement for international trade, not only for Filipinos wishing to export to most countries, but also for foreign operators wanting to sell their products on the Philippine market. It is important to understand the roots of the success of HACCP, because it is not just a constraint to be complied with. If well understood, HACCP is an opportunity for Filipino farmers to take the lead in the highly competitive context of the 21st century’s global economy. With the globalization of trade, the geographical and cultural gaps between food producers and food consumers have never been larger. Filipinos eat imported rice and Europeans eat imported shrimps. But the growing distance between producing and consuming areas is also a factor that breeds misunderstanding and sometimes distrust, whether justified or not. -

Revision of ST61, Nor Was the Stockholm Agreement of 1961 the First Broadcasting Frequency Plan

SPECTRUM PLANNING Revision of ST61— Lessons learned from history J. Doeven Nozema, the Netherlands Over the next few years, the Stockholm Frequency Plan of 1961 will be revised to produce a new plan for digital broadcasting in the European Broadcasting Area. In this article, the author describes some of the lessons learned from history which must be taken into account when revising the original Stockholm Plan. Introduction In June 2001, the ITU Council decided – on the basis of a proposal from European countries – that the Stock- holm Agreement of 1961 (ST61) shall be revised in order to make a new frequency plan for digital broadcast- ing. The conference to revise ST61 will consist of two sessions. The first session is planned for May 2004; the second session is foreseen in 2005 or 2006. This conference will not be the first revision of ST61, nor was the Stockholm Agreement of 1961 the first broadcasting frequency plan. Since the start of broadcasting there has been a need for a-priori frequency plans; i.e. frequency plans that are made at a conference and are valid for a long period of time, often 15 or more years. Actually, the Stockholm Plan of 1961 has been in use for more than 40 years! In retrospect, the results achieved at some earlier broadcasting conferences 1 can be reviewed and weighted against the principal conditions required for establishing a-priori plans. The conclusions drawn from this exer- cise may then provide a valuable lesson from history as we prepare for the revision of ST61. A-priori plans Around 1920, broadcasting started in a number of countries. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 10.5.2017 SWD(2017) 160

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 10.5.2017 SWD(2017) 160 final PART 61/62 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Europe's Digital Progress Report 2017 EN EN Europe’s Digital Progress Report-2017 Telecom chapter SWEDEN 1. Competitive environment Coverage SE-2015 SE-2016 EU-2016 Fixed broadband coverage (total) 99% 99% 98% Fixed broadband coverage (rural) 94% 91% 93% Fixed NGA coverage (total) 76% 79% 76% Fixed NGA coverage (rural) 14% 22% 40% 4G coverage (average of operators) no data 100% 84% Source: Broadband Coverage Study (IHS and Point Topic). Data as of October 2015 and October 2016 Fixed broadband market The Swedish broadband market is characterised by rapidly growing consumer demand for ultrafast broadband and a corresponding rapidly declining consumer demand for slower broadband. On the fixed broadband market, fibre subscriptions continued to increase over the reporting period (+17% of fibre LAN compared to 2015). The Swedish broadband market also featured a slight increase (+4%) in cable TV subscriptions and conversely a substantial decrease in xDSL subscriptions (-10%)1. Sweden is currently among the EU countries with a very advanced fixed broadband coverage baseline. Currently, Sweden scores well above the EU average for overall 4G coverage (100% against 84% for the EU) but lags behind the EU average for fixed next-generation access (NGA) coverage in rural areas (21% against 40% for the EU). The role of municipalities in providing local fibre is remarkable in Sweden. The fibre market is fragmented, with approximately 180 local fibre networks complementing the offer of the incumbent and the cable sector. Municipalities’ networks offer their services via what are called communication operators operating the network of the dark fibre owner. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 4,959,862 Davidov Et Al

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 4,959,862 Davidov et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 25, 1990 (54) ACTIVE MULTICHANNEL VIDEO CATV Networks”; Proceedings of Int. Broadcasting PROCESSING HUB FOR OPTIMUM Convention, (London, 9/76), pp. 228-231. TRANSTION FROM FIBERTO COAX B. White, "The Fibre Optic Pipedream Comes True in Video"; "Broadcasting Systems & Operation'; (8/79, 75 Inventors: Mircho A. Davidov, Danville; pp. 352-356). Kamaljit Singh, San Jose, both of Calif. Primary Examiner-Stephen C. Buczinski Assistant Examiner-Bernarr Earl Gregory 73 Assignee: Catel Telecommunications, Inc., Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Flehr, Hohbach, Test, Fremont, Calif. Albritton & Herbert (21) Appl. No.: 187,305 57 ABSTRACT An active multichannel video processing hub which 22 Filed: Apr. 28, 1988 provides optinum transition from fiber to coaxial cable, provides optimum trading of bandwidth for signal to 51) Int. Cl. ............................................. H04N 7/167 noise ratio. Fiber optic links have a very large band 52 U.S. C. .......................................... 380/10; 455/6; width capability. Larger distances can be covered with 358/86 fiber optic links without repeaters. This offers not only 58 Field of Search .......................... 358/86; 455/3-6; saving in maintenance, but has no radiation and offers 370/1, 3, 4, 11, 73; 375/62, 65, 66; 332/17, 120, bidirectional capabilities not easily achievable with 145 coax-based trunks. Scrambled signals are transmitted over the fiber and converted to VSB-AM signals at the (56) References Cited hub for transmission over the coaxial portion of the U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS trunk. This keeps the bulky and complex headend 2,506,672 5/1950 Kell et al. -

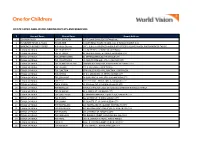

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

Annual Report 2019 (Pdf / 10

AnnualKernaufgabe Report Infrakstrukturausbau 2019 NetworksNachhaltige for Verbindungen the digital world schaffe 1 Editorial 2 Foreword 6 Energy 8 Market watch 12 Security of supply and network expansion 22 Consumer protection and advice 26 Rulings, activities and proceedings 38 International cooperation 42 Telekommunications 44 Market watch 64 Consumer protection and advice 76 Rulings, activities and proceedings 86 International cooperation 92 Post 94 Market watch 102 Consumer protection and advice 108 Rulings, activities and proceedings 112 International cooperation 116 Rail 118 Market watch 122 Rulings, activities and proceedings 130 International cooperation 132 Core tasks and organisation 139 List of abbreviations 142 Contacting the Bundesnetzagentur 143 Publisher's details Bundesnetzagentur Strategic Plan 2020 The Bundesnetzagentur is required under section 122(2) of the Telecommunications Act (TKG) to include a strategic plan in its Annual Report, listing matters of legal and economic policy in telecommunications to be addressed by the Bundesnetzagentur in the current year. In addition, the Bundesnetzagentur includes all its main projects in all its fields of activity in which issues of fundamental importance are expected in 2020. The strategic plan can be found at www.bundesnetzagentur.de/vorhabenplan EDITORIAL | 1 Greater competition and transparency in the markets for energy, telecommunications, railways and post strengthen Germany’s industrial competitiveness and make it more attractive as a place to do business. The consumers profit from this as well. Through its decisions, the Bundesnetzagentur ensures fair competition among the providers in the energy and telecommunications markets. It also promotes continued development of competition in the post and railway sectors. In order to prevent congestion, the networks must be expanded. -

Annual Licence Fees for 900 Mhz and 1800 Mhz Spectrum Statement

Annual licence fees for 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum Statement Annexes 9-13 Annual licence fees for 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum Contents 9 Technical and commercial evidence 3 10 Annualisation: supporting material 40 11 Marginal bidder analysis of paired 2.6 GHz spectrum in the absence of Niche 66 12 Statutory instrument 68 13 Glossary of terms 72 Annual licence fees for 900 MHz and 1800 MHz spectrum Annex 9 9 Technical and commercial evidence Introduction A9.1 This annex contains further material on technical and commercial evidence which supports our assessment in Sections 1 and 2 on future spectrum availability and in Section 3 on estimating lump-sum values. It covers: a) Possibility of greater certainty around spectrum availability; b) Technical and commercial evidence relating to the relative values of 800 MHz and 900 MHz spectrum; c) Technical and commercial evidence relating to the value of 1800 MHz spectrum; d) Network cost modelling; and e) Qualcomm’s trade of licences for 1.4 GHz spectrum. A9.2 We outlined our provisional views on the first and fourth of these issues in Annex 9 of our August 2014 consultation, and on the third issue in Annex 7 of the August 2014 consultation.1 Stakeholders provided a numbers of comments on these views. Additionally, H3G and Vodafone made arguments relating to the second issue of the technical and commercial value of 900 MHz spectrum relative to 800 MHz. We considered these comments as part of our assessment of technical and commercial evidence in Annex 9 of our February 2015 consultation. -

Spectrum Requirements for Terrestrial Television Broadcasting in the UHF Frequency Band in Region 1 and the Islamic Republic of Iran

Report ITU-R BT.2302-0 (04/2014) Spectrum requirements for terrestrial television broadcasting in the UHF frequency band in Region 1 and the Islamic Republic of Iran BT Series Broadcasting service (television) ii Rep. ITU-R BT.2302-0 Foreword The role of the Radiocommunication Sector is to ensure the rational, equitable, efficient and economical use of the radio- frequency spectrum by all radiocommunication services, including satellite services, and carry out studies without limit of frequency range on the basis of which Recommendations are adopted. The regulatory and policy functions of the Radiocommunication Sector are performed by World and Regional Radiocommunication Conferences and Radiocommunication Assemblies supported by Study Groups. Policy on Intellectual Property Right (IPR) ITU-R policy on IPR is described in the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC referenced in Annex 1 of Resolution ITU-R 1. Forms to be used for the submission of patent statements and licensing declarations by patent holders are available from http://www.itu.int/ITU-R/go/patents/en where the Guidelines for Implementation of the Common Patent Policy for ITU-T/ITU-R/ISO/IEC and the ITU-R patent information database can also be found. Series of ITU-R Reports (Also available online at http://www.itu.int/publ/R-REP/en) Series Title BO Satellite delivery BR Recording for production, archival and play-out; film for television BS Broadcasting service (sound) BT Broadcasting service (television) F Fixed service M Mobile, radiodetermination, amateur and related satellite services P Radiowave propagation RA Radio astronomy RS Remote sensing systems S Fixed-satellite service SA Space applications and meteorology SF Frequency sharing and coordination between fixed-satellite and fixed service systems SM Spectrum management Note: This ITU-R Report was approved in English by the Study Group under the procedure detailed in Resolution ITU-R 1. -

Spectrum for Television Broadcasting and 700Mhz

สํานักงานคณะกรรมการกิจการกระจายเสียง กิจการโทรทัศน และกิจการโทรคมนาคม (สํานักงาน กสทช.) Office of the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) Spectrum for Television Broadcasting and IMT 700 MHz in Thailand Supatrasit Suansook 21 August 2017 Broadcasting Technology and Engineering Bureau Office of the NBTC facebook : Broadcast.Engineering.NBTC Topics Digital Terrestrial Television in Thailand : Overview Frequency Planning and Frequency Utilization for Analogue and Digital Terrestrial Television in Thailand Steps to Release 470 MHz for Digital TV and 700 MHz for IMT in Thailand Challenges Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 2 หนาที่ 2 Digital Terrestrial Television in Thailand: Overview Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 3 Current Digital TV Networks 4 Network Operators operating 5 Digital TV Networks 1 Network = 1 Multiplex = Using 1 Radio Frequency per area Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 4 หนาที่ Current Status of Multiplexes and TV Programs Current: 26 TV Program being broadcasted in DTT Platform (by 5 MUXs) as of March 2016 • 22 Commercial Programs * • 4 Public Programs Target: 48 TV Program (6 MUXs) • 24 Commercial Programs • 12 Public Programs • 12 Community Programs * 2 Commercial Program Licenses were withdrawn. Supatrasit Suansook (Office of the NBTC, Thailand) Page 5 หนาที่ Digital TV Coverage and Rollout Plan Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Phase 4 (Apr’13 – Jun’14) (Jun’14 – Jun’15) (Jun’15 – Jun’16) (Jun’16 – Jun’17) 50% 80% 90% 95% 168 sites -

Data-Over-Cable Service Interface Specifications Downstream RF

Data-Over-Cable Service Interface Specifications Downstream RF Interface Specification CM-SP-DRFI-I05-070223 ISSUED Notice This DOCSIS® specification is a cooperative effort undertaken at the direction of Cable Television Laboratories, Inc. (CableLabs®) for the benefit of the cable industry. Neither CableLabs, nor any other entity participating in the creation of this document, is responsible for any liability of any nature whatsoever resulting from or arising out of use or reliance upon this document by any party. This document is furnished on an AS-IS basis and neither CableLabs, nor other participating entity, provides any representation or warranty, express or implied, regarding its accuracy, completeness, or fitness for a particular purpose. © Copyright 2005 - 2007 Cable Television Laboratories, Inc. All rights reserved. CM-SP-DRFI-I05-070223 Data-Over-Cable Service Interface Specifications Document Status Sheet Document Control Number: CM-SP-DRFI-I05-070223 Document Title: Downstream RF Interface Specification Revision History: I01 – Released 08/05/05 I02 – Released 12/09/05 I03 – Released 01/06/06 I04 – Released 12/22/06 I05 – Released 02/23/07 Date: February 23, 2007 Status: Work in Draft Issued Closed Progress Distribution Restrictions: Author CL/Member CL/ Member/ Public Only Vendor Key to Document Status Codes: Work in Progress An incomplete document, designed to guide discussion and generate feedback that may include several alternative requirements for consideration. Draft A document in specification format considered largely complete, but lacking review by Members and vendors. Drafts are susceptible to substantial change during the review process. Issued A stable document, which has undergone rigorous member and vendor review and is suitable for product design and development, cross-vendor interoperability, and certification testing. -

RADIO FREQUENCY SPECTRUM ASSIGNMENT PLAN for the FREQUENCY BAND 2300 to 2400 Mhz for CONSULTATION

STAATSKOERANT, 14 NOVEMBER 2014 No. 38214 129 NOTICE 1016 OF 2014 INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF SOUTH AFRICA I C A aS A PURSUANT TO SECTION 4 (1) OF THE ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS ACT 2005, (ACT NO. 36 OF 2005) HEREBY ISSUES A NOTICE REGARDING THE DRAFT RADIO FREQUENCY SPECTRUM ASSIGNMENT PLAN FOR THE FREQUENCY BAND 2300 TO 2400 MHz FOR CONSULTATION. 1. The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa ("the Authority"), hereby publishes Draft Radio Frequency Spectrum Assignment Plan for the frequency band 2300 to 2400 MHz for consultation in terms of sections 2 (d), (e) and 4, read with sections 30, 31(4), and 33 of the Electronic Communications Act (Act No. 36 of 2005) and read with Regulation 3 of the Radio Frequency Spectrum Regulations 2011 and read with the IMT Roadmap 2014. 2. This Radio Frequency Spectrum Assignment Plan supersedes any previous spectrum assignment arrangements for the same spectrum location. 3. Interested persons are hereby invited to submit written representations, including an electronic version of the representation in Microsoft Word, of their views on the Draft Radio Frequency Spectrum Assignment Plan for the frequency band 2300 to 2400 MHz by no later than 16h00 on Friday 28th November 2014. This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 130 No. 38214 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 14 NOVEMBER 2014 Page 2/190 4. Written representations or enquiries may be directed to: The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) Pinmill Farm Block A 164 Katherine Street South Africa or Private Bag X10002 Sandton 2146 Attention: Mr Manyaapelo Richard Makgotlho e-mail: rmaRqot 5.