Proquest Document 5/5 Eva Lundell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

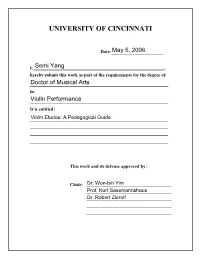

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

La Société Philharmonique

The Historic New Orleans Collection & Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra Carlos Miguel Prieto Adelaide Wisdom Benjamin Music Director and Principal Conductor Pr eseNT Identity, History, Legacy La Société PhiLh ar monique Thomas Wilkins, conductor Walter Harris Jr., speaker Kisma Jordan, soprano Joseph Meyer, violin Jean-Baptiste Monnot, organ/piano Phumzile Sojola, tenor THursday, February 10, 2011 Cathedral-basilica of st. Louis, King of France New Orleans, Louisiana Fr Iday, February 11, 2011 slidell High school slidell, Louisiana The Historic New Orleans Collection and the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra gratefully acknowledge rev. Msgr. Crosby W. Kern and the staff of the st. Louis Cathedral for their generous support and assistance. The musical culture of New Orleans’s free people of color and their descendants is one of the most extraordinary aspects of Louisiana history, and it is part of a larger, shared legacy. Only within the context of the development of african music in the New World can the contributions of these sons and daughters of Louisiana be fully appreciated. The first africans arrived in the New World with the initial wave of spanish colonization in the early sixteenth century. Interactions among european, african, and indigenous populations yielded new forms of cultural expression—although african music in the New World remained strongly dependent on wind instruments (such as ivory trumpets), drums, and call-and-response patterns. as early as 1572, africans were gathering in front of the famous aztec calendar stone in Mexico City on sunday afternoons to dance and sing. When Viceroy antonio de Mendoza triumphantly entered Lima on august 31, 1551, his procession’s route was lined with african drummers. -

AFE EPOSIT 0. American Organ and Piano Co

KUNKEL'S MUSICAL REVIEW, JANUARY, 1889. 1 MAJOR AND MINOR. 1\lme. Scalchl will be heard during the winter months at the Moritz RosAnthal, the Ronmanean pianist, opened his en· Imperial Opera house in St. Petersburg. gagement in this country in Boston. He has a wonderful technical skill and is meeting with the most pronounced "Esclarmonde" is the name of a new four net opera by They a.re endeavoring to abolish the encore system in En- success. Massenet. gland. It would be a boon in mauy ways. At the second symphonic concert of the Russian Musica Sembrich received $2,400 for two engagements at Co· Adele A us Der Ohe gave the sixty-eighth piano forte re- Society, at St. .Petersburg, Rubinstein's·new symphonic poem penhagen. cital of the Ladies' Musical Society of Omaha. "Don Qui 11:ote," was col(;.ly received, though it is said to pos· Madame Patti sang at the Paris Grand Opera, under the sess considerable merit. Pauline Lucca says that her coming to America will end composer's baton, the part of Juliet in M. Gounod's opera. he~ career on the stage. One more has been added to the settings of Goethe's Faust. At her Sixth Piano Recital, comprising works of American that of Max Zenger. The others are by Spohr, Voss, Bishop, Mr. an · ~ Mrs. Henschel will leave England in March for a composers only, MRs. 'l'HoMs of N. Y., played E. R. Kroeger's Beaucourt, Blum, Bertin, Meyer, Ku~ler. rle Pallaert, Gordigi- long tour m the United States. -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 25,1905-1906, Trip

ACADEMY OF MUSIC, PHILADELPHIA. BostonSympRony Qrctiestia WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor. Twenty-first Season in Philadelphia* PROGRAMME OF THE FIRST CONCERT MONDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 6, AT 8. J 5 PRECISELY. Hale. With Historical and Descriptive Notes by Philip Published by C. A. ELLIS, Manager. l A PIANO FOR THE MUSICALLY INTELLIGENT classes, artists' pianos If Pianos divide into two and popular pianos. The proportion of the first class to the second class is precisely the proportion of cultivated music lovers to the rest of society. A piano, as much as a music library, is the index of the musical taste of its owner. are among the musically intelligent, the ^f If you PIANO is worth your study. You will appreciate the " theory and practice of its makers : Let us have an artist's piano ; therefore let us employ the sci- ence, secure the skill, use the materials, and de- vote the time necessary to this end. Then let us count the cost and regulate the -price." Tf In this case hearings not seeing, is believing. Let us send you a list of our branch houses and sales agents (located in all important cities), at whose warerooms our pianos may be heard. Boston, Mass., 492 Boylston Street New York, 139 Fifth Avenue Chicago, Wabash Avenue and Jackson Boulevard Boston Symphony Orchestra. PERSONNEL. Twenty-fifth Season, 1905-1906. WILHELM GERICKE, Conductor First Viouns Hess, Willy, Concertmeister. Adamowski, T. Ondricek, K. Mahn, F Back, A. Roth, O. Krafft, W. Eichheim, H. Sokoloff, N. Kuntz, D. Hoffmann, J Fiedler, E. Mullaly, J. Moldauer, A. Strube, G. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects -

Download Booklet

557943bk Cello US 3+3 Rev 8/10/05 5:41 PM Page 1 Maria Kliegel A native of Dillenburg, but living in Essen since 1975, Maria Kliegel is one of the leading cello virtuosi of our time VIRTUOSO CELLO and the most recorded on CD. She took up her studies with Janos Starker at Indiana University in the United States, and won first prize at the American College Competition, at the First German Music Competition, and at the Concours Aldo Parisot. After her triumph at the Rostropovich Competition in 1981, she began a series of ENCORES outstanding international concerts and tours, playing in Basle, with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington and with the Orchestre National de France in Paris, always accompanied by Mstislav Rostropovich Bach • Schubert • Popper • Debussy • Ravel conducting. Successful concert events have led to numerous sessions for radio, television and for record labels. In 1990, when she recorded Alfred Schnittke’s First Cello Concerto, the Russian composer recognized her interpretation as the standard recording of the work, a judgement echoed by critics when the recording appeared on Offenbach • Rachmaninov • Shostakovich Marco Polo, and later on Naxos (8.554465). Maria Kliegel appears regularly as a guest soloist at venues all over the world, as well as with her duo partner, the American pianist Nina Tichman, and, since 2001, with her and the violinist Ida Bieler in the newly established Xyrion Tro. She has an exceptionally wide repertoire and her versatility Maria Kliegel, Cello and interest in exploring newer works has stimulated contemporary composers to write music for her to perform, for example Hommage à Nelson by Wilhelm Kaiser-Lindemann (recorded on Naxos 8.554485) , dedicated to Raimund Havenith, Piano Nelson Mandela. -

Julius Stockhausen's Early Performances of Franz Schubert's

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Julius Stockhausen’s Early Performances of Franz Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin NATASHA LOGES Franz Schubert’s huge song cycle Die schöne mances of Die schöne Müllerin by the baritone Müllerin, D. 795, is a staple of recital halls and Julius Stockhausen (1826–1906), as well as the record collections, currently available in no responses of his audiences, collaborators, and fewer than 125 recordings as an uninterrupted critics.3 The circumstances surrounding the first sequence of twenty songs.1 In the liner notes of complete performance in Vienna’s Musikverein one recent release, the tenor Robert Murray on 4 May 1856, more than three decades after observes that the hour-long work requires con- the cycle was composed in 1823, will be traced.4 siderable stamina in comparison with operatic Subsequent performances by Stockhausen will roles.2 Although Murray does not comment on the demands the work makes on its audience, this is surely also a consideration, and certainly 3For an account of early Schubert song performance in a one that shaped the early performance history variety of public and private contexts, see Eric Van Tassel, of the work. This article offers a detailed con- “‘Something Utterly New:’ Listening to Schubert Lieder. sideration of the pioneering complete perfor- 1: Vogl and the Declamatory Style,” Early Music 25/4 (November 1997): 702–14. A general history of the Lied in concert focusing on the late nineteenth century is in Ed- ward F. Kravitt, “The Lied in 19th-Century Concert Life,” This study was generously funded by the British Academy Journal of the American Musicological Society 18 (1965): in 2015–16. -

O Legado De Pablo De Sarasate

O LEGADO DE PABLO DE SARASATE Lígia Maria Leitão Soares Silva Tese apresentada à Universidade de Évora para obtenção do Grau de Doutor em Música e Musicologia Especialidade: Interpretação ORIENTADORA: Professora Doutora Vanda de Sá ÉVORA, NOVEMBRO DE 2018 INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO E FORMAÇÃO AVANÇADA ¡Un genio! ¡He practicado catorce horas diarias durante treinta y siete años, y ahora me llaman genio! Pablo de Sarasate ~ iii ~ ~ iv ~ À memória dos meus pais ~ v ~ ~ vi ~ Agradecimentos Concluir um doutoramento em Música e Musicologia na especialidade de Interpretação implica uma longa trajectória em que a conciliação do trabalho escrito com a prática do instrumento dificilmente se consegue fazer de modo regular e constante. Este trabalho não teria sido possível sem o apoio de diversas pessoas às quais deixo aqui os meus sinceros agradecimentos. Começo por agradecer à Professora Doutora Vanda de Sá, orientadora deste trabalho, a disponibilidade e o interesse, as sugestões que fez e a generosidade com que disponibilizou algumas fontes. Agradeço ainda a forma estimulante como contribuiu para o alargamento de algumas problemáticas iniciais, a amizade demonstrada e a disponibilidade para ler e aconselhar sobre o conteúdo das notas aos programas que elaborei para os recitais que realizei como parte deste doutoramento. Agradeço ao Professor Doutor Félix Andrievsky todos os conhecimentos que me transmitiu ao longo dos anos em que trabalhei com ele e sem os quais não teria sido possível realizar este trabalho. Agradeço também a disponibilidade que continua a ter para mim, cerca de trinta anos após o primeiro contacto, o estímulo, os conselhos e o interesse com que ouviu grande parte do repertório que interpretei nos recitais. -

Four Further Spohr Mysteries

FOUR FURTHER SPOHR MYSTERIES by Keith Warsop Introduction T\ REVIOUS Spohr mysteries were considered in Spohr Journal2T for Winter 2000, pages lJ $-19 (1. The Rondo for Violin and Harp, "Op.88"; 2. Psalm XX[V, Op.97a;3. Trio for I Violin, Viola and Guitar. WoO.138; 4. Konzertsflick for Clarinet and Orchestra) and in Spohr Journal\Sfor Winter z}}l,pages 30-35 (1, Spohr's slow movements; 2. Spohr and Bach; 3. Spohr's Russian tune; 4. Spohr's Harp Trio). Fresh light was thrown on some of these subjects while others remain mysterious. 1. Cadenzas to Beethoven's Violin Concerto, WoO.46 The fact that Spohr wrote cadenzas for Beethoven's Violin Concerto may come as a surprise to many outside the circle of Spohr scholarship. After all, the general prejudice is that Spohr was out of sympathy with all except the works of Beethoven's first period, such as the string quartets Op.l8. Leslie Orrey, for instance, states: "He was unsympathetic to the later Beethoven; in the whole of his Autobiography there is no reference to the greatest of all violin concertos." [BncHenecH 1958]. As Spohr's cadenzas were not published until 1896 they have remained little known and hardly ever played. They appeared in print in the Edition Chamot in London (No.741) though credited to aLeipzig printer. The title page reads: "Edition Charnot". Trois Cadences pour le CoNcEnto DE VloLoN de L.veN BgeruovEN par Louis Spohr. 741. Price 3A. Printed by C'G.Rdder, Leipzig' This edition gives no clue as to the date of composition but in his Spohr thematic catalogue, Folker G6thel speculates about two possible occasions when Spohr might have written the cadenzas fG6rffir, 198i].