Alaska's State Bird (Willow Ptarmigan)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

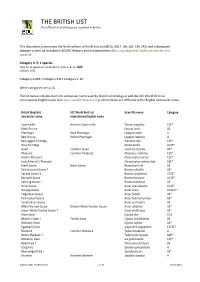

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

The Sleeping Habit of the Willow Ptarmigan

638 GeneralNotes [Oct.[Auk day the bird was found dead by Mr. Wilkin at the edge of the marsh. It had been shot and left by someoneunknown. The bird was turned over to New York Con- servation Department officers and has now been placed in the New York State Museum collection. The bird was a female in excellentbreeding-plumage condition and contained eggs. It weighed 11s/{ pounds, had a wing-spreadof 97 inches,and a length of 54 inches. It was examined in the flesh by both authors of this note.-- GORDO• M. M•AD•, M.D., Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester,New York, A•D C•,a¾•ro• B. S•ao•ms, Supt. of ConservationEducation, Albany, New York. The sleeping habit of the Willow Ptarmigan.--A frequent statement regard- ing the Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopuslagopus) is that in winter when it goesto roost it drops from flight into the snow, completely burying itself and leaving no tracks that might lead predators to it. E. W. Nelson made this observation years ago in Alaska, and it is given also by Sandys and Van Dyke in their book, 'Upland Game Birds.' Bent (U.S. Nat. Mus. Bull., 162: 194, 1932) in writing on Allen's Ptarmigan of Newfoundland, quotes •I. R. Whitaker as stating that they roost in a shallow scratchingin the snow and are frequently buried by drifts and imprisonedto their death. On Southampton Island, Sutton records the Willow Ptarmigan as roosting and feeding in the same area without attempt at concealment. One night seven slept for the night in sevenconsecutive footprints of his track acrossthe snow. -

Alaska Birds & Wildlife

Alaska Birds & Wildlife Pribilof Islands - 25th to 27th May 2016 (4 days) Nome - 28th May to 2nd June 2016 (5 days) Barrow - 2nd to 4th June 2016 (3 days) Denali & Kenai Peninsula - 5th to 13th June 2016 (9 days) Scenic Alaska by Sid Padgaonkar Trip Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Forrest Davis RBT Alaska – Trip Report 2016 2 Top Ten Birds of the Tour: 1. Smith’s Longspur 2. Spectacled Eider 3. Bluethroat 4. Gyrfalcon 5. White-tailed Ptarmigan 6. Snowy Owl 7. Ivory Gull 8. Bristle-thighed Curlew 9. Arctic Warbler 10. Red Phalarope It would be very difficult to accurately describe a tour around Alaska - without drowning the narrative in superlatives to the point of nuisance. Not only is it an inconceivably huge area to describe, but the habitats and landscapes, though far north and less biodiverse than the tropics, are completely unique from one portion of the tour to the next. Though I will do my best, I will fail to encapsulate what it’s like to, for example, watch a coastal glacier calving into the Pacific, while being observed by Harbour Seals and on-looking Murrelets. I can’t accurately describe the sense of wilderness felt looking across the vast glacial valleys and tundra mountains of Nome, with Long- tailed Jaegers hovering overhead, a Rock Ptarmigan incubating eggs near our feet, and Muskoxen staring at us strangers to these arctic expanses. Finally, there is Denali: squinting across jagged snowy ridges that tower above 10,000 feet, mere dwarfs beneath Denali standing 20,300 feet high, making everything else in view seem small, even toy-like, by comparison. -

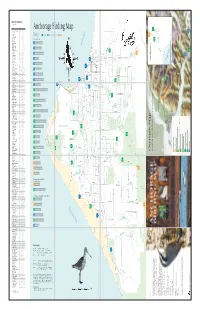

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs* -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Revision of Molt and Plumage

The Auk 124(2):ART–XXX, 2007 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2007. Printed in USA. REVISION OF MOLT AND PLUMAGE TERMINOLOGY IN PTARMIGAN (PHASIANIDAE: LAGOPUS SPP.) BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY CONSIDERATIONS Peter Pyle1 The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. Box 1346, Point Reyes Station, California 94956, USA Abstract.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt. A spring contour molt was signifi cantly later and more extensive in females than in males, a summer contour molt was signifi cantly earlier and more extensive in males than in females, and complete summer–fall wing and contour molts were statistically similar in timing between the sexes. Completeness of feather replacement, similarities between the sexes, and comparison of molts with those of related taxa indicate that the white winter plumage of ptarmigan should be considered the basic plumage, with shi s in hormonal and endocrinological cycles explaining diff erences in plumage coloration compared with those of other phasianids. Assignment of prealternate and pre- supplemental molts in ptarmigan necessitates the examination of molt evolution in Galloanseres. Using comparisons with Anserinae and Anatinae, I considered a novel interpretation: that molts in ptarmigan have evolved separately within each sex, and that the presupplemental and prealternate molts show sex-specifi c sequences within the defi nitive molt cycle. Received 13 June 2005, accepted 7 April 2006. Key words: evolution, Lagopus, molt, nomenclature, plumage, ptarmigan. Revision of Molt and Plumage Terminology in Ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.) Based on Evolutionary Considerations Rese.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt. -

Stock Code Description Stock Code Description

STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION A MIXED C2 COLONIAL A1 ARBOR ACRES C3 CHAUMIERE BB-NL A2 ANDREWS-NL C3 CORBETT A2 BABCOCK C4 DAVIS A3 CAREY C5 HARCO A5 COLONIAL C6 HARDY A6 EURIBRID C7 PARKS A7 GARBER C8 ROWLEY A8 H AND N-NL C9 GUILFORD-NL A8 H AND N C9 TATUM A9 HALEY C10 HENNING-NL A10 HUBBARD C10 WELP A11 LOHMANN C11 SCHOONOVER A12 MERRILL C12 IDEAL A13 PARKS C19 NICHOLAS-NL A14 SHAVER C35 ORLOPP LARGE BROAD-NL A15 TATUM C57 ROSE-A-LINDA-NL A16 WELP C122 ORLOPP BROAD-NL A17 HANSON C129 KENT-NL A18 DEKALB C135 B.U.T.A., LARGE-NL A19 HYLINE C142 HYBRID DOUBLE DIAMOND MEDIUM-NL A38 KENT-NL C143 HYBRID LARGE-NL A45 MARCUM-NL C144 B.U.T.A., MEDIUM-NL A58 ORLOPP-NL C145 NICHOLAS 85-NL B MIXED C146 NICHOLAS 88-NL B1 ARBOR ACRES C147 HYBRID CONVERTER-NL B2 COLONIAL C148 HYBRID EXTREME-NL B3 CORBETT C149 MIXED B4 DAVIS D MIXED B5 DEKALB WARREN D1 ARBOR ACRES B6 HARCO D2 BRADWAY B7 HARDY D3 COBB B8 LAWTON D4 COLONIAL B9 ROWLEY D5 HARDY B10 WELP D6 HUBBARD B11 CARGILL D7 LAWTON B12 SCHOONOVER D8 PILCH B13 CEBE D9 WELP B14 OREGON D10 PENOBSCOT B15 IDEAL D11 WROLSTAD SMALL-NL C MIXED D11 CEBE, RECESSIVE C1 ARBOR ACRES D12 IDEAL C2 BROADWHITE-NL 1 STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION E MIXED N13 OLD ENGLISH, RED PYLE E1 COLONIAL N14 OLD ENGLISH, WHITE E2 HUBBARD N15 OLD ENGLISH, BLACK E3 BOURBON, RED-NL N16 OLD ENGLISH, SPANGLED E3 ROWLEY N17 PIT E4 WELP N18 OLD ENGLISH E5 SCHOONOVER N19 MODERN E6 CEBE N20 PIT, WHITE HACKLE H MIXED N21 SAM BIGHAM H1 ARBOR ACRES N22 MCCLANHANS H1 ARBOR ACRES N23 CLIPPERS H2 COBB N24 MINER BLUES -

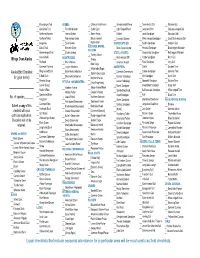

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

304 Isaev Layout 1

CHANGE IN PTARMIGAN NUMBERS IN YAKUTIA ARKADY P. ISAEV Institute for Biological Problems of the Cryolithozone, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, pr. Lewina 41, Yakutsk 677007, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Counts of Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus) and Rock Ptarmigan (L. muta) have been conducted for as long as 25 years in some areas of the Russian Republic of Yakutia in tundra, taiga, and along the ecotone of these landscapes. The largest counts of Willow Ptarmigan occur in the tundra and forest-tundra. Willow Ptarmigan numbers fluctuate, and the length of the “cycles” vary among areas in Yakutia. Fluctuations in ptarmigan numbers are greater in the tundra and forest-tundra than in the northern taiga. Rock Ptarmigan are common in the mountain areas and tundra of Yakutia, and their numbers also fluctuate. Factors affecting ptarmigan populations are weather shifts in early spring and unfavorable weather during hatching. A decrease in the num- ber of Willow Ptarmigan in the taiga belt of Yakutia is most likely explained by a greater anthro- pogenic load. Current Willow and Rock Ptarmigan populations in Yakutia appear stable, except for central and southern areas. Received 1 February 2011, accepted 31 May 2011. ISAEV, A. P. 2011. Change in ptarmigan number in Yakutia. Pages 259–266 in R. T. Watson, T. J. Cade, M. Fuller, G. Hunt, and E. Potapov (Eds.). Gyrfalcons and Ptarmigan in a Changing World, Volume II. The Peregrine Fund, Boise, Idaho, USA. http://dx.doi.org/10.4080/gpcw.2011.0304 Key words: Willow Ptarmigan, Rock Ptarmigan, Yakutia, Russia, count changes. -

Intergeneric Galliform Hybrids: a Review

INTERGENERIC GALLIFORM HYBRIDS : A REVIEW BY TONY J. PETERLE Henry Seebohm, in “The Birds of Siberia” (1901: Sol-502), makes this cogent observa- tion: “The subject of the interbreeding of nearly-allied birds in certain localities where their geographical ranges meet or overlap, and the almost identical subject of the existence of intermediate forms in the intervening district between the respective geographical ranges of nearly-allied birds, is one which has not yet received the attention which it deserves from ornithologists. The older brethren of the fraternity have always pooh-pooh’d any attempt to explain some of these complicated facts of nature by the theory of interbreeding, and have looked upon the suggestion that hybridisation was anything but an abnormal circumstance as one of the lamest modes of getting out of an ornithological difficulty.” The following sum- mary will show that interbreeding of galliform genera has often been observed: indeed that two wholly different intergeneric hybrids, one of the Old World, one of the New, have been recovered so often that they can hardly be considered ‘abnormal’ except in a very limited sense. The Old World hybrid referred to results from the crossing of the Blackcock (Lyvurus) and Capercaillie (Tetrao). DeWinton (1894: 448) said that “of all hybrids among birds in a wild state this one seems to be the most frequent.” Authors seem to be in agreement that the hybrid results principally, if not always, from the interbreeding of male Lyrurus with fe- male Tetreo in areas throughout which (a) extension of range is taking place, or (b) one or the other genus is rare, e.g., Scotland, where Tetrao has been introduced following extirpation (Millais, 1906: 55-56; DeWinton, 1894). -

Willow Ptarmigan Study Alaska Peninsula April-May 2012

WILLOW PTARMIGAN STUDY Alaska Peninsula April - May 2012 Photo: USFWS, L. Julian Kevin J. Payne and Susan E. Savage December 2012 KEY WORDS: Alaska Peninsula; Alaska Peninsula NWR, Becharof NWR, Lagopus lagopus, line transect surveys, willow ptarmigan U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Peninsula / Becharof National Wildlife Refuge PO Box 277 King Salmon, AK 99613 i The mission of the National Wildlife Refuge System is to administer a national network of lands and waters for the conservation, management and where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources and their habitats within the United States for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans. Suggested Citation: Payne, K.J. and S.E. Savage. 2012. Willow Ptarmigan Study - Alaska Peninsula, April - May 2012. USFWS, Alaska Peninsula/Becharof NWR Report, King Salmon, Alaska. ii CONTENTS CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ iv List of Appendices ......................................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................