13 Willow Ptarmigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Tactile and Visual Stimuli of Eggs and Nest for Termination of Egg Laying of Red Junglefowl

The Auk 112(2):483-488, 1995 IMPORTANCE OF TACTILE AND VISUAL STIMULI OF EGGS AND NEST FOR TERMINATION OF EGG LAYING OF RED JUNGLEFOWL THEO MEIJER Departmentof Ethology,University of BieIefeld,P.O. Box100131, 33501Bielefeld, Germany ABSTRACT.--Experimentswere conductedto separatethe influence of tactile and visual stimuli emanating from the nest or eggs on the development of incubation behavior, the terminationof egg laying, and the determinationof clutchsize. Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus spadiceus)hens, whose eggswere left inside the nest (experiment 1), receivedboth tactile and visualinformation, remained in the nestbox longer,and stoppedlaying after eight days (or sixeggs). Sixteen or 17females incubated. Leaving only the firstegg in the nest(experiment 2) gavesimilar results. When the eggslaid were placedunder a wire-meshbasket (experiment 3) suchthat the hen couldsee but not touchthe accumulatingeggs, laying stopped two days (or one egg) later than in experiment1, and mosthens "incubated"on the empty nestuntil the nestbox wasremoved. Surprisingly, when eggswere continuallyremoved (experiment 4), hensalso incubated progressively more, stopped laying after two weeks(or nine eggs), and then sat on the empty nest for one or more days. Stimulation of the brood patch by the nest alone led to more incubationand to termination of egg laying. Visual stimuli alone providedby eggsaccelerated both processesand were sufficientfor one-half of the hens to maintainfull incubationbehavior. Red Junglefowl do not appearto judgeclutch size visually. Received9 December1993, accepted25 February1994. DURING THE BREEDINGSEASON, a female has to nest. The few experimentsby which tactile in- make two important "decisions":when to start formation coming from the brood patch was laying, and when to stop laying. -

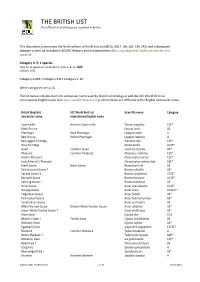

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

The Sleeping Habit of the Willow Ptarmigan

638 GeneralNotes [Oct.[Auk day the bird was found dead by Mr. Wilkin at the edge of the marsh. It had been shot and left by someoneunknown. The bird was turned over to New York Con- servation Department officers and has now been placed in the New York State Museum collection. The bird was a female in excellentbreeding-plumage condition and contained eggs. It weighed 11s/{ pounds, had a wing-spreadof 97 inches,and a length of 54 inches. It was examined in the flesh by both authors of this note.-- GORDO• M. M•AD•, M.D., Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester,New York, A•D C•,a¾•ro• B. S•ao•ms, Supt. of ConservationEducation, Albany, New York. The sleeping habit of the Willow Ptarmigan.--A frequent statement regard- ing the Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopuslagopus) is that in winter when it goesto roost it drops from flight into the snow, completely burying itself and leaving no tracks that might lead predators to it. E. W. Nelson made this observation years ago in Alaska, and it is given also by Sandys and Van Dyke in their book, 'Upland Game Birds.' Bent (U.S. Nat. Mus. Bull., 162: 194, 1932) in writing on Allen's Ptarmigan of Newfoundland, quotes •I. R. Whitaker as stating that they roost in a shallow scratchingin the snow and are frequently buried by drifts and imprisonedto their death. On Southampton Island, Sutton records the Willow Ptarmigan as roosting and feeding in the same area without attempt at concealment. One night seven slept for the night in sevenconsecutive footprints of his track acrossthe snow. -

Reproductive Ecology of Tibetan Eared Pheasant Crossoptilon Harmani in Scrub Environment, with Special Reference to the Effect of Food

Ibis (2003), 145, 657–666 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Reproductive ecology of Tibetan Eared Pheasant Crossoptilon harmani in scrub environment, with special reference to the effect of food XIN LU1* & GUANG-MEI ZHENG2 1Department of Zoology, College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China 2Department of Ecology, College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China We studied the nesting ecology of two groups of the endangered Tibetan Eared Pheasants Crossoptilon harmani in scrub environments near Lhasa, Tibet, during 1996 and 1999–2001. One group received artificial food from a nunnery prior to incubation whereas the other fed on natural food. This difference in the birds’ nutritional history allowed us to assess the effects of food on reproduction. Laying occurred between mid-April and early June, with a peak at the end of April or early May. Eggs were laid around noon. Adult females produced one clutch per year. Clutch size averaged 7.4 eggs (4–11). Incubation lasted 24–25 days. We observed a higher nesting success (67.7%) than reported for other eared pheasants. Pro- visioning had no significant effect on the timing of clutch initiation or nesting success, and a weak effect on egg size and clutch size (explaining 8.2% and 9.1% of the observed variation, respectively). These results were attributed to the observation that the unprovisioned birds had not experienced local food shortage before laying, despite spending more time feeding and less time resting than the provisioned birds. Nest-site selection by the pheasants was non-random with respect to environmental variables. Rock-cavities with an entrance aver- aging 0.32 m2 in size and not deeper than 1.5 m were greatly preferred as nest-sites. -

Alaska Birds & Wildlife

Alaska Birds & Wildlife Pribilof Islands - 25th to 27th May 2016 (4 days) Nome - 28th May to 2nd June 2016 (5 days) Barrow - 2nd to 4th June 2016 (3 days) Denali & Kenai Peninsula - 5th to 13th June 2016 (9 days) Scenic Alaska by Sid Padgaonkar Trip Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Forrest Davis RBT Alaska – Trip Report 2016 2 Top Ten Birds of the Tour: 1. Smith’s Longspur 2. Spectacled Eider 3. Bluethroat 4. Gyrfalcon 5. White-tailed Ptarmigan 6. Snowy Owl 7. Ivory Gull 8. Bristle-thighed Curlew 9. Arctic Warbler 10. Red Phalarope It would be very difficult to accurately describe a tour around Alaska - without drowning the narrative in superlatives to the point of nuisance. Not only is it an inconceivably huge area to describe, but the habitats and landscapes, though far north and less biodiverse than the tropics, are completely unique from one portion of the tour to the next. Though I will do my best, I will fail to encapsulate what it’s like to, for example, watch a coastal glacier calving into the Pacific, while being observed by Harbour Seals and on-looking Murrelets. I can’t accurately describe the sense of wilderness felt looking across the vast glacial valleys and tundra mountains of Nome, with Long- tailed Jaegers hovering overhead, a Rock Ptarmigan incubating eggs near our feet, and Muskoxen staring at us strangers to these arctic expanses. Finally, there is Denali: squinting across jagged snowy ridges that tower above 10,000 feet, mere dwarfs beneath Denali standing 20,300 feet high, making everything else in view seem small, even toy-like, by comparison. -

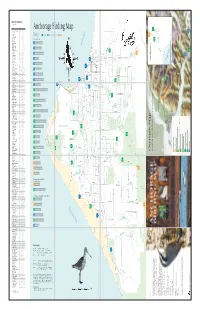

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs* -

A Checklist of Somerset Birds

A Checklist of Somerset Birds The Somerset List to the end of 2014 contains 357 species. Using the BOURC classification 336 are in Category A, 18 in B and three in C. Golden Pheasant has been removed from the list as it is considered that there never was a self-sustaining population in Somerset. An explanation of the BOUC classification is given below. A Species that have been recorded in an apparently natural state at least once since 1 January 1950. B Species that have been recorded in an apparently natural state at least prior to 31 December 1949, but have not been recorded subsequently. C1 Naturalized introduced species - species that have occurred only as a result of introduction, e.g. Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiacus C2 Naturalized established species – species with established populations resulting from introduction by Man, but which also occur in an apparently natural state, e.g. Greylag Goose Anser anser C3 Naturalized re-established species – species with populations successfully re-established by Man in areas of former occurrence, e.g. Red Kite Milvus milvus. C4 Naturalized feral species – domesticated species with populations established in the wild, e.g. Rock Pigeon (Dove)/Feral Pigeon Columba livia C5 Vagrant naturalized species – species from established naturalized populations abroad, e.g. possibly some Ruddy Shelducks Tadorna ferruginea occurring in Britain. There are currently no species in category C5. C6 Former naturalized species - species formerly placed in C1 whose naturalized populations are either no longer self-sustaining or are considered extinct, e.g. Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae. D Species that would otherwise appear in Category A except that there is reasonable doubt that they have ever occurred in a natural state. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Trichostrongylus Cramae N. Sp. (Nematoda), a Parasite of Bob-White Quail (Colinus Virginianus) M.-C

Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp., Key-words: Trichostrongylus. Birds. Europe. USA. Trichos- 1993, 68 : n° 1, 43-48. trongylus tenuis. T. cramae n. sp. Lagopus scoticus. Pavo cris- tatus. Perdix perdix. Phasianus colchicus. Colinus virginianus. Mémoire. Mots-clés : Trichostrongylus. Oiseaux. Europe. USA. Trichos trongylus tenuis. T. cramae n. sp. Lagopus scoticus. Pavo cris- tatus. Perdix perdix. Phasianus colchicus. Colinus virginianus. TRICHOSTRONGYLUS CRAMAE N. SP. (NEMATODA), A PARASITE OF BOB-WHITE QUAIL (COLINUS VIRGINIANUS) M.-C. DURETTE-DESSET*, A. G. CHABAUD*, J. MOORE** Summary ---------------------------------------------------------- Cram (1925, 1927) incorrectly identified as T. pergracilis (now the cuticular striation, the relative distances between the second, a synonym of T. tenuis) what was in reality an undescribed spe third and fourth bursal papillae and the configuration of the dorsal cies in Colinus virginianus. ray. Red grouse (Lagopus scoticus), the type host of T. pergra Trichostrongylus cramae n. sp. is proposed for T. pergracilis cilis, was in fact found to be parasitized by T. tenuis, confirming sensu Cram, 1927 nec Cobbold, 1873 from C. virginianus from the synonymy of T. pergracilis and T. tenuis. USA. It differs from T. tenuis (Mehlis in Creplin, 1846) as regards Résumé : Trichostrongylus cramae n. sp. (Nematoda) parasite de Colinus virginianus. Cram (1925, 1927) a identifié par erreur comme étant T. per Il se différencie de T. tenuis (Mehlis in Creplin, 1846) par la gracilis, maintenant considéré comme un synonyme de T. tenuis, striation cuticulaire, les distances relatives entre les papilles bur- ce qui était en réalité une espèce non décrite parasite de Colinus sales 2, 3 et 4, et par la configuration de la côte dorsale. -

Revision of Molt and Plumage

The Auk 124(2):ART–XXX, 2007 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2007. Printed in USA. REVISION OF MOLT AND PLUMAGE TERMINOLOGY IN PTARMIGAN (PHASIANIDAE: LAGOPUS SPP.) BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY CONSIDERATIONS Peter Pyle1 The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. Box 1346, Point Reyes Station, California 94956, USA Abstract.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt. A spring contour molt was signifi cantly later and more extensive in females than in males, a summer contour molt was signifi cantly earlier and more extensive in males than in females, and complete summer–fall wing and contour molts were statistically similar in timing between the sexes. Completeness of feather replacement, similarities between the sexes, and comparison of molts with those of related taxa indicate that the white winter plumage of ptarmigan should be considered the basic plumage, with shi s in hormonal and endocrinological cycles explaining diff erences in plumage coloration compared with those of other phasianids. Assignment of prealternate and pre- supplemental molts in ptarmigan necessitates the examination of molt evolution in Galloanseres. Using comparisons with Anserinae and Anatinae, I considered a novel interpretation: that molts in ptarmigan have evolved separately within each sex, and that the presupplemental and prealternate molts show sex-specifi c sequences within the defi nitive molt cycle. Received 13 June 2005, accepted 7 April 2006. Key words: evolution, Lagopus, molt, nomenclature, plumage, ptarmigan. Revision of Molt and Plumage Terminology in Ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.) Based on Evolutionary Considerations Rese.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt. -

Stock Code Description Stock Code Description

STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION A MIXED C2 COLONIAL A1 ARBOR ACRES C3 CHAUMIERE BB-NL A2 ANDREWS-NL C3 CORBETT A2 BABCOCK C4 DAVIS A3 CAREY C5 HARCO A5 COLONIAL C6 HARDY A6 EURIBRID C7 PARKS A7 GARBER C8 ROWLEY A8 H AND N-NL C9 GUILFORD-NL A8 H AND N C9 TATUM A9 HALEY C10 HENNING-NL A10 HUBBARD C10 WELP A11 LOHMANN C11 SCHOONOVER A12 MERRILL C12 IDEAL A13 PARKS C19 NICHOLAS-NL A14 SHAVER C35 ORLOPP LARGE BROAD-NL A15 TATUM C57 ROSE-A-LINDA-NL A16 WELP C122 ORLOPP BROAD-NL A17 HANSON C129 KENT-NL A18 DEKALB C135 B.U.T.A., LARGE-NL A19 HYLINE C142 HYBRID DOUBLE DIAMOND MEDIUM-NL A38 KENT-NL C143 HYBRID LARGE-NL A45 MARCUM-NL C144 B.U.T.A., MEDIUM-NL A58 ORLOPP-NL C145 NICHOLAS 85-NL B MIXED C146 NICHOLAS 88-NL B1 ARBOR ACRES C147 HYBRID CONVERTER-NL B2 COLONIAL C148 HYBRID EXTREME-NL B3 CORBETT C149 MIXED B4 DAVIS D MIXED B5 DEKALB WARREN D1 ARBOR ACRES B6 HARCO D2 BRADWAY B7 HARDY D3 COBB B8 LAWTON D4 COLONIAL B9 ROWLEY D5 HARDY B10 WELP D6 HUBBARD B11 CARGILL D7 LAWTON B12 SCHOONOVER D8 PILCH B13 CEBE D9 WELP B14 OREGON D10 PENOBSCOT B15 IDEAL D11 WROLSTAD SMALL-NL C MIXED D11 CEBE, RECESSIVE C1 ARBOR ACRES D12 IDEAL C2 BROADWHITE-NL 1 STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION STOCK CODE DESCRIPTION E MIXED N13 OLD ENGLISH, RED PYLE E1 COLONIAL N14 OLD ENGLISH, WHITE E2 HUBBARD N15 OLD ENGLISH, BLACK E3 BOURBON, RED-NL N16 OLD ENGLISH, SPANGLED E3 ROWLEY N17 PIT E4 WELP N18 OLD ENGLISH E5 SCHOONOVER N19 MODERN E6 CEBE N20 PIT, WHITE HACKLE H MIXED N21 SAM BIGHAM H1 ARBOR ACRES N22 MCCLANHANS H1 ARBOR ACRES N23 CLIPPERS H2 COBB N24 MINER BLUES -

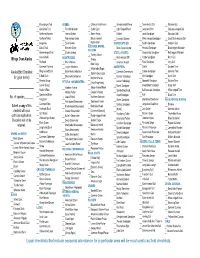

Wings Over Alaska Checklist

Blue-winged Teal GREBES a Chinese Pond-Heron Semipalmated Plover c Temminck's Stint c Western Gull c Cinnamon Teal r Pied-billed Grebe c Cattle Egret c Little Ringed Plover r Long-toed Stint Glacuous-winged Gull Northern Shoveler Horned Grebe a Green Heron Killdeer Least Sandpiper Glaucous Gull Northern Pintail Red-necked Grebe Black-crowned r White-rumped Sandpiper a Great Black-backed Gull a r Eurasian Dotterel c Garganey a Eared Grebe Night-Heron OYSTERCATCHER Baird's Sandpiper Sabine's Gull c Baikal Teal Western Grebe VULTURES, HAWKS, Black Oystercatcher Pectoral Sandpiper Black-legged Kittiwake FALCONS Green-winged Teal [Clark's Grebe] STILTS, AVOCETS Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Red-legged Kittiwake c Turkey Vulture Canvasback a Black-winged Stilt a Purple Sandpiper Ross' Gull Wings Over Alaska ALBATROSSES Osprey Redhead a Shy Albatross a American Avocet Rock Sandpiper Ivory Gull Bald Eagle c Common Pochard Laysan Albatross SANDPIPERS Dunlin r Caspian Tern c White-tailed Eagle Ring-necked Duck Black-footed Albatross r Common Greenshank c Curlew Sandpiper r Common Tern Alaska Bird Checklist c Steller's Sea-Eagle r Tufted Duck Short-tailed Albatross Greater Yellowlegs Stilt Sandpiper Arctic Tern for (your name) Northern Harrier Greater Scaup Lesser Yellowlegs c Spoonbill Sandpiper Aleutian Tern PETRELS, SHEARWATERS [Gray Frog-Hawk] Lesser Scaup a Marsh Sandpiper c Broad-billed Sandpiper a Sooty Tern Northern Fulmar Sharp-shinned Hawk Steller's Eider c Spotted Redshank Buff-breasted Sandpiper c White-winged Tern Mottled Petrel [Cooper's