Grouse News 38 Newsletter of the Grouse Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 623 at 8 June 2021 Category A 605 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Capercaillie Western Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus C3E* Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix AE Ptarmigan Rock Ptarmigan Lagopus muta A Red Grouse Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus lagopus A Red-legged Partridge Alectoris rufa C1E* Grey Partridge Perdix perdix AC2E* Quail Common Quail Coturnix coturnix AE* Pheasant Common Pheasant Phasianus colchicus C1E* Golden Pheasant Chrysolophus pictus C1E* Lady Amherst’s Pheasant Chrysolophus amherstiae C6E* Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser -

The Sleeping Habit of the Willow Ptarmigan

638 GeneralNotes [Oct.[Auk day the bird was found dead by Mr. Wilkin at the edge of the marsh. It had been shot and left by someoneunknown. The bird was turned over to New York Con- servation Department officers and has now been placed in the New York State Museum collection. The bird was a female in excellentbreeding-plumage condition and contained eggs. It weighed 11s/{ pounds, had a wing-spreadof 97 inches,and a length of 54 inches. It was examined in the flesh by both authors of this note.-- GORDO• M. M•AD•, M.D., Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester,New York, A•D C•,a¾•ro• B. S•ao•ms, Supt. of ConservationEducation, Albany, New York. The sleeping habit of the Willow Ptarmigan.--A frequent statement regard- ing the Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopuslagopus) is that in winter when it goesto roost it drops from flight into the snow, completely burying itself and leaving no tracks that might lead predators to it. E. W. Nelson made this observation years ago in Alaska, and it is given also by Sandys and Van Dyke in their book, 'Upland Game Birds.' Bent (U.S. Nat. Mus. Bull., 162: 194, 1932) in writing on Allen's Ptarmigan of Newfoundland, quotes •I. R. Whitaker as stating that they roost in a shallow scratchingin the snow and are frequently buried by drifts and imprisonedto their death. On Southampton Island, Sutton records the Willow Ptarmigan as roosting and feeding in the same area without attempt at concealment. One night seven slept for the night in sevenconsecutive footprints of his track acrossthe snow. -

The Impact of Wind Energy Facilities on Grouse: a Systematic Review

Journal of Ornithology (2020) 161:1–15 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-019-01696-1 REVIEW The impact of wind energy facilities on grouse: a systematic review Joy Coppes1 · Veronika Braunisch1,2 · Kurt Bollmann3 · Ilse Storch4 · Pierre Mollet5 · Veronika Grünschachner‑Berger6,7 · Julia Taubmann1,4 · Rudi Suchant1 · Ursula Nopp‑Mayr8 Received: 17 January 2019 / Revised: 1 July 2019 / Accepted: 18 July 2019 / Published online: 1 August 2019 © Deutsche Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2019 Abstract There is increasing concern about the impact of the current boom in wind energy facilities (WEF) and associated infra- structure on wildlife. However, the direct and indirect efects of these facilities on the mortality, occurrence and behaviour of rare and threatened species are poorly understood. We conducted a literature review to examine the potential impacts of WEF on grouse species. We studied whether grouse (1) collide with wind turbines, (2) show behavioural responses in relation to wind turbine developments, and (3) if there are documented efects of WEF on their population sizes or dynam- ics. Our review is based on 35 sources, including peer-reviewed articles as well as grey literature. Efects of wind turbine facilities on grouse have been studied for eight species. Five grouse species have been found to collide with wind turbines, in particular with the towers. Fifteen studies reported behavioural responses in relation to wind turbine facilities in grouse (seven species), including spatial avoidance, displacement of lekking or nesting sites, or the time invested in breeding vs. non-breeding behaviour. Grouse were afected at up to distances of 500 m by WEF infrastructure, with indications of efects also at bigger distances. -

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

Alaska Birds & Wildlife

Alaska Birds & Wildlife Pribilof Islands - 25th to 27th May 2016 (4 days) Nome - 28th May to 2nd June 2016 (5 days) Barrow - 2nd to 4th June 2016 (3 days) Denali & Kenai Peninsula - 5th to 13th June 2016 (9 days) Scenic Alaska by Sid Padgaonkar Trip Leader(s): Forrest Rowland and Forrest Davis RBT Alaska – Trip Report 2016 2 Top Ten Birds of the Tour: 1. Smith’s Longspur 2. Spectacled Eider 3. Bluethroat 4. Gyrfalcon 5. White-tailed Ptarmigan 6. Snowy Owl 7. Ivory Gull 8. Bristle-thighed Curlew 9. Arctic Warbler 10. Red Phalarope It would be very difficult to accurately describe a tour around Alaska - without drowning the narrative in superlatives to the point of nuisance. Not only is it an inconceivably huge area to describe, but the habitats and landscapes, though far north and less biodiverse than the tropics, are completely unique from one portion of the tour to the next. Though I will do my best, I will fail to encapsulate what it’s like to, for example, watch a coastal glacier calving into the Pacific, while being observed by Harbour Seals and on-looking Murrelets. I can’t accurately describe the sense of wilderness felt looking across the vast glacial valleys and tundra mountains of Nome, with Long- tailed Jaegers hovering overhead, a Rock Ptarmigan incubating eggs near our feet, and Muskoxen staring at us strangers to these arctic expanses. Finally, there is Denali: squinting across jagged snowy ridges that tower above 10,000 feet, mere dwarfs beneath Denali standing 20,300 feet high, making everything else in view seem small, even toy-like, by comparison. -

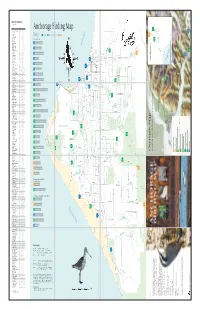

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs* -

1 Rural Affairs and Environment Committee

RURAL AFFAIRS AND ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE WILDLIFE AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT (SCOTLAND) BILL WRITTEN SUBMISSION FROM DR ADAM WATSON Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Bill, consultation I request members of the Rural Affairs & Environment Committee to take the decisive action that is long overdue to end the widespread and increasing illegal persecution of protected Scottish raptors. Leading MSPs and Scottish Ministers in the previous Labour/Lib Dem coalition and the present SNP administration have condemned this unlawful activity, calling it a national disgrace. However, it continues unabated, involving poisoning as well as shooting and other illegal activities. Indeed, it has increased, as is evident from the marked declines in numbers and distribution of several species that are designated as in the highest national and international ranks for protection. In 1943 I began in upper Deeside to study golden eagles, which have now been monitored there for much longer than anywhere else in the world. I have also studied peregrines and other Scottish raptor species, and snowy owls in arctic Canada. This research resulted in many papers in scientific journals. An example was in 1989 when I was author of a scientific paper that reviewed data on golden eagles from 1944 to 1981. It showed the adverse effects of eagle persecution on grouse moors, in contrast to deer forests where the birds were generally protected or ignored by resident deerstalkers. Also it showed how a decline of such persecution during the Second World War, when many grouse-moor keepers were in the armed services, led to a notable increase of resident eagle pairs on grouse moors. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE for CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where Science Comes to Life

RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE RSPB CENTRE FOR CONSERVATION SCIENCE Where science comes to life Contents Knowing 2 Introducing the RSPB Centre for Conservation Science and an explanation of how and why the RSPB does science. A decade of science at the RSPB 9 A selection of ten case studies of great science from the RSPB over the last decade: 01 Species monitoring and the State of Nature 02 Farmland biodiversity and wildlife-friendly farming schemes 03 Conservation science in the uplands 04 Pinewood ecology and management 05 Predation and lowland breeding wading birds 06 Persecution of raptors 07 Seabird tracking 08 Saving the critically endangered sociable lapwing 09 Saving South Asia's vultures from extinction 10 RSPB science supports global site-based conservation Spotlight on our experts 51 Meet some of the team and find out what it is like to be a conservation scientist at the RSPB. Funding and partnerships 63 List of funders, partners and PhD students whom we have worked with over the last decade. Chris Gomersall (rspb-images.com) Conservation rooted in know ledge Introduction from Dr David W. Gibbons Welcome to the RSPB Centre for Conservation The Centre does not have a single, physical Head of RSPB Centre for Conservation Science Science. This new initiative, launched in location. Our scientists will continue to work from February 2014, will showcase, promote and a range of RSPB’s addresses, be that at our UK build the RSPB’s scientific programme, helping HQ in Sandy, at RSPB Scotland’s HQ in Edinburgh, us to discover solutions to 21st century or at a range of other addresses in the UK and conservation problems. -

The Cairngorm Club Journal 110, 2013

76 BOOK REVIEWS The Cairngorms: 100 Years of Mountaineering. Greg Strange, 2101. Scottish Mountaineering Trust, 400pp. ISBN 978-1-907233-1-1 This magisterial volume by the author of a well-used SMC climbing guide to the Cairngorms, covers the century from 1893 (the ascent of the Douglas-Gibson Gully) onwards. To this Club, founded six years earlier, that choice of starting date may seem odd, even contentious, but it signals that the focus of this book is firmly about climbing on rock and ice, even if there are occasional mentions of skiing, bothies, some environmental issues (hill tracks, the Lurcher's Gully Inquiry, but not climate change) and even walks. Given that focus, it is hard to fault the book, at least from a non/ex-climber's viewpoint: it takes the reader through each main first ascent with a happy mixture of background information on the participants, the day (and/or night) as a whole, and sufficient detail on the main pitches, including verbatim (or at least reported) conversations. Delightfully, most pages carry a photograph of the relevant route, landscape or character(s), the accumulation of which must represent a tremendous effort in contacting club and personal archives. Throughout the century the energy and endurance of the pioneers are evident, perhaps most to those who have themselves tramped the approach miles, and sampled Cairngorm weather and terrain, even if they have never attempted the technical feats here described. The 12 main chapters cover the period in a balanced way, but the pride of place must go to the central chapters on 'The Golden Years' (1950-1960) in 56 pages, 'The Ice Revolution' (1970-1972) in 38 pages and 'The Quickening Pace' (1980-1985) in 58 pages. -

Update of the Situation of the Cantabrian Capercaillie Tetrao Urogallus Cantabricus: an Ongoing Decline Maria José Bañuelos & Mario Quevedo

Grouse News 25 Newsletter of Grouse Specialist Group Update of the situation of the Cantabrian capercaillie Tetrao urogallus cantabricus: an ongoing decline Maria José Bañuelos & Mario Quevedo In a previous number of Grouse News (Bañuelos et al. 2004) we reported the drastic decline that Cantabrian capercaillie Tetrao urogallus cantabricus had apparently suffered in two decades, from the early 1980’s to 2000 - 2001. Based on extensive evaluation of lek occupancy, about 50% of the display areas had been deserted, and the number of remaining cocks was roughly estimated at 300. Accordingly, Cantabrian capercaillie was listed as endangered in Spain, and became the only subspecies of capercaillie qualifying as endangered according to IUCN criteria (Storch et al. 2006). This capercaillie population occupies a very southerly range for a tetraonid (Quevedo et al. 2006a), and has recently been identified as an evolutionary significant unit because of its unique ecological and genetic characteristics (Rodríguez- Muñoz et al. 2007). Between 2005 and 2007 a new extensive lek survey was performed in the northern watershed of the range (Asturias), over a territory that comprises more than 50% of the population. Almost all known display areas (N=364) were repeatedly surveyed during the lekking season (April-May). Surveys were performed during the day, looking for signs such as feathers, fresh droppings or footprints, so that results were mainly presence-absence data. Occupancy surveys during the day were mostly chosen over more traditional lek counts at dawn to minimize disturbances, but also because the previous survey (2000/2001) showed that less than 10% of the occupied sites had more than one cock. -

Revision of Molt and Plumage

The Auk 124(2):ART–XXX, 2007 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2007. Printed in USA. REVISION OF MOLT AND PLUMAGE TERMINOLOGY IN PTARMIGAN (PHASIANIDAE: LAGOPUS SPP.) BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY CONSIDERATIONS Peter Pyle1 The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. Box 1346, Point Reyes Station, California 94956, USA Abstract.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt. A spring contour molt was signifi cantly later and more extensive in females than in males, a summer contour molt was signifi cantly earlier and more extensive in males than in females, and complete summer–fall wing and contour molts were statistically similar in timing between the sexes. Completeness of feather replacement, similarities between the sexes, and comparison of molts with those of related taxa indicate that the white winter plumage of ptarmigan should be considered the basic plumage, with shi s in hormonal and endocrinological cycles explaining diff erences in plumage coloration compared with those of other phasianids. Assignment of prealternate and pre- supplemental molts in ptarmigan necessitates the examination of molt evolution in Galloanseres. Using comparisons with Anserinae and Anatinae, I considered a novel interpretation: that molts in ptarmigan have evolved separately within each sex, and that the presupplemental and prealternate molts show sex-specifi c sequences within the defi nitive molt cycle. Received 13 June 2005, accepted 7 April 2006. Key words: evolution, Lagopus, molt, nomenclature, plumage, ptarmigan. Revision of Molt and Plumage Terminology in Ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.) Based on Evolutionary Considerations Rese.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt.