Molecular Determinants of PDLIM2 in Suppressing HTLV-I Tax-Mediated Tumorigenesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioinformatic Analysis of Structure and Function of LIM Domains of Human Zyxin Family Proteins

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Bioinformatic Analysis of Structure and Function of LIM Domains of Human Zyxin Family Proteins M. Quadir Siddiqui 1,† , Maulik D. Badmalia 1,† and Trushar R. Patel 1,2,3,* 1 Alberta RNA Research and Training Institute, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Lethbridge, 4401 University Drive, Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4, Canada; [email protected] (M.Q.S.); [email protected] (M.D.B.) 2 Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Infectious Disease, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, 3330 Hospital Drive, Calgary, AB T2N 4N1, Canada 3 Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2E1, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to the work. Abstract: Members of the human Zyxin family are LIM domain-containing proteins that perform critical cellular functions and are indispensable for cellular integrity. Despite their importance, not much is known about their structure, functions, interactions and dynamics. To provide insights into these, we used a set of in-silico tools and databases and analyzed their amino acid sequence, phylogeny, post-translational modifications, structure-dynamics, molecular interactions, and func- tions. Our analysis revealed that zyxin members are ohnologs. Presence of a conserved nuclear export signal composed of LxxLxL/LxxxLxL consensus sequence, as well as a possible nuclear localization signal, suggesting that Zyxin family members may have nuclear and cytoplasmic roles. The molecular modeling and structural analysis indicated that Zyxin family LIM domains share Citation: Siddiqui, M.Q.; Badmalia, similarities with transcriptional regulators and have positively charged electrostatic patches, which M.D.; Patel, T.R. -

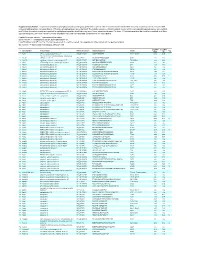

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. Large-scale quantitative phosphoproteomic profiling was performed on paired vehicle- and hormone-treated mTAL-enriched suspensions (n=3). A total of 654 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 374 unique phosphoproteins were identified. The peptide sequence, phosphorylation site(s), and the corresponding protein name, gene symbol, and RefSeq Accession number are reported for each phosphopeptide identified in any one of three experimental pairs. For those 414 phosphopeptides that could be quantified in all three experimental pairs, the mean Hormone:Vehicle abundance ratio and corresponding standard error are also reported. Peptide Sequence column: * = phosphorylated residue Site(s) column: ^ = ambiguously assigned phosphorylation site Log2(H/V) Mean and SE columns: H = hormone-treated, V = vehicle-treated, n/a = peptide not observable in all 3 experimental pairs Sig. column: * = significantly changed Log 2(H/V), p<0.05 Log (H/V) Log (H/V) # Gene Symbol Protein Name Refseq Accession Peptide Sequence Site(s) 2 2 Sig. Mean SE 1 Aak1 AP2-associated protein kinase 1 NP_001166921 VGSLT*PPSS*PK T622^, S626^ 0.24 0.95 PREDICTED: ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A 2 Abca12 (ABC1), member 12 XP_237242 GLVQVLS*FFSQVQQQR S251^ 1.24 2.13 3 Abcc10 multidrug resistance-associated protein 7 NP_001101671 LMT*ELLS*GIRVLK T464, S468 -2.68 2.48 4 Abcf1 ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 NP_001103353 QLSVPAS*DEEDEVPVPVPR S109 n/a n/a 5 Ablim1 actin-binding LIM protein 1 NP_001037859 PGSSIPGS*PGHTIYAK S51 -3.55 1.81 6 Ablim1 actin-binding -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Signalling 6 1

r r r Cell Signalling Biology Michael J. Berridge Module 6 Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Signalling 6 1 Module 6 Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Signalling Synopsis The function and efficiency of cell signalling pathways are very dependent on their organization both in space and time. With regard to spatial organization, signalling components are highly organized with respect to their cellular location and how they transmit information from one region of the cell to another. This spatial organization of signalling pathways depends on the molecular interactions that occur between signalling components that use signal transduction domains to construct signalling pathways. Very often, the components responsible for information transfer mechanisms are held in place by being attached to scaffolding proteins to form macromolecular signalling complexes. Sometimes these macromolecular complexes can be organized further by being localized to specific regions of the cell, as found in lipid rafts and caveolae or in the T-tubule regions of skeletal and cardiac cells. Another feature of the spatial aspects concerns the local Another important temporal aspect is timing and signal and global aspects of signalling. The spatial organization of integration, which relates to the way in which functional signalling molecules mentioned above can lead to highly interactions between signalling pathways are determined localized signalling events, but when the signalling mo- by both the order and the timing of their presentations. lecules are more evenly distributed, signals can spread The organization of signalling systems in both time and more globally throughout the cell. In addition, signals space greatly enhances both their efficiency and versatility. -

Actin Bundling Via LIM Domains

[Plant Signaling & Behavior 3:5, 320-321; May 2008]; ©2008 Landes Bioscience Article Addendum Actin bundling via LIM domains Clément Thomas,* Monika Dieterle, Sabrina Gatti, Céline Hoffmann, Flora Moreau, Jessica Papuga and André Steinmetz Centre de Recherche Public-Santé; Val Fleuri 84; L-1526; Luxembourg Key words: Actin-binding proteins, actin-bundling, cysteine-rich proteins, cytoskeleton, LIM domain. The LIM domain is defined as a protein-protein interaction module involved in the regulation of diverse cellular processes including gene expression and cytoskeleton organization. We distribute. have recently shown that the tobacco WLIM1, a two LIM domain-containing protein, is able to bind to, stabilize and bundle actin filaments, suggesting that it participates to the regulation of actin cytoskeleton structure and dynamics. In the December issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry we report a domain analysis not that specifically ascribes the actin-related activities of WLIM1 to its two LIM domains. Results suggest that LIM domains func- Figure 1. Domain maps for wild-type WLIM1 (A) and GFP-fused chimeric tion synergistically in the full-length protein to achieve optimal 3xWLIM1 (B). A. WLIM1 basically comprises a short N-terminal domain (Nt), two LIM domains (LIM1Do and LIM2), an interLIM spacer (IL) and a C-terminal activities. Here we briefly summarize relevant data regarding the domain (Ct). B. 3xWLIM1 consists of three tandem WLIM1 copies. This chi- actin-related properties/functions of two LIM domain-containing meric protein has been fused in C-terminus to GFP and transiently expressed proteins in plants and animals. In addition, we provide further in tobacco BY2 cells. -

Early Evolution of the LIM Homeobox Gene Family

Srivastava et al. BMC Biology 2010, 8:4 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7007/8/4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Early evolution of the LIM homeobox gene family Mansi Srivastava1*, Claire Larroux2, Daniel R Lu1, Kareshma Mohanty1, Jarrod Chapman3, Bernard M Degnan2, Daniel S Rokhsar1,3 Abstract Background: LIM homeobox (Lhx) transcription factors are unique to the animal lineage and have patterning roles during embryonic development in flies, nematodes and vertebrates, with a conserved role in specifying neuronal identity. Though genes of this family have been reported in a sponge and a cnidarian, the expression patterns and functions of the Lhx family during development in non-bilaterian phyla are not known. Results: We identified Lhx genes in two cnidarians and a placozoan and report the expression of Lhx genes during embryonic development in Nematostella and the demosponge Amphimedon. Members of the six major LIM homeobox subfamilies are represented in the genomes of the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis, and the placozoan Trichoplax adhaerens. The hydrozoan cnidarian, Hydra magnipapillata, has retained four of the six Lhx subfamilies, but apparently lost two others. Only three subfamilies are represented in the haplosclerid demosponge Amphimedon queenslandica. A tandem cluster of three Lhx genes of different subfamilies and a gene containing two LIM domains in the genome of T. adhaerens (an animal without any neurons) indicates that Lhx subfamilies were generated by tandem duplication. This tandem cluster in Trichoplax is likely a remnant of the original chromosomal context in which Lhx subfamilies first appeared. Three of the six Trichoplax Lhx genes are expressed in animals in laboratory culture, as are all Lhx genes in Hydra. -

Characterization and Sequence Analysis of Cysteine and Glycine-Rich Protein 3 in Egyptian Native Cattle and River Native Buffalo Cdna Sequences

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 10(16), pp. 3055-3061, 18 April, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB DOI: 10.5897/AJB10.1953 ISSN 1684–5315 © 2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Characterization and sequence analysis of cysteine and glycine-rich protein 3 in Egyptian native cattle and river native buffalo cDNA sequences Ahlam A. Abou Mossallam, Nevien M. Sabry, Eman R. Mahfouz*, Mona A. Bibars and Soheir M. El Nahas Department of Cell Biology, Genetic Engineering Division, National Research Center, Dokki, Giza, Egypt. Accepted 3 February, 2011 Cysteine and glycine rich protein, CSRP3 also referred to as the muscle LIM protein (MLP), has been investigated in native Egyptian cattle and buffalo (river buffalo). RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were conducted from different tissue samples. Primers specific for CSRP3 were designed using known cDNA sequences of Bos taurus published in database with different accession numbers. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed and products were purified and sequenced. Sequence analysis and alignment were carried out using CLUSTAL W (1.83). Multiple nucleotide sequence alignment between CSRP3 cDNA amplicons of native buffalo and cattle revealed 89% identity. B. taurus CSRP3 mRNA (Cardiac LIM protein) [NM 001024689.2] showed 85 and 87% identity in nucleic acid sequences and 82 and 84% homology in amino acid sequences with native cattle and buffalo, respectively. A 90% homology was detected between the amino acid sequences of river buffalo and native cattle. Fourty nine translated amino acids out of 51 in both buffalo and cattle are found to be part of the conserved CSRP3 LIM1 domain protein which comprises 57 codons. -

Genetic Basis of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Bos, J.M. Publication date 2010 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bos, J. M. (2010). Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 Chapter 4 Echocardiographic-Determined Septal Morphology in Z-Disc Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Jeanne L. Theis*, J. Martijn Bos *, Virginia B. Bartleson, Melissa L. Will, Josepha Binder, Matteo Vatta, Jeffrey A. Towbin, Bernard J. Gersh, Steve R. Ommen, Michael J. Ackerman * These authors contributed equally to this study Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 351(4): 896 – 902 Abstract Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) can be classified into at least 4 major anatomic subsets based upon the septal contour, and the location and extent of hypertrophy: reverse curvature-, sigmoidal-, apical-, and neutral contour-HCM. -

The LIM-Only Protein FHL2 Is a Serum-Inducible Transcriptional Coactivator of AP-1

The LIM-only protein FHL2 is a serum-inducible transcriptional coactivator of AP-1 Aurore Morlon and Paolo Sassone-Corsi* Institut de Ge´ne´ tique et de Biologie Mole´culaire et Cellulaire, B. P. 10142, 67404 Illkirch–Strasbourg, France Edited by Peter K. Vogt, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 10, 2003 (received for review October 1, 2002) Proteins with LIM domains have been implicated in transcriptional in proliferation and differentiation of cardiomyocytes is AP-1 regulation. The four and half LIM domain (FHL) group of LIM-only (20, 21). Because the constituents of AP-1, the oncoproteins Fos proteins is composed of five members, some of which have been and Jun belong to the bZip class of transcription factors (22–26), shown to have intrinsic activation function. Here we show that as CREB and CREM (27, 28), the possibility that FHL2 could FHL2 is the only member of the family whose expression is interact with Fos and Jun is appealing. inducible upon serum stimulation in cultured cells. Induction of Here we show that the expression of the gene encoding FHL2 FHL2 is coordinated in time with the increased levels of two is inducible by serum. This characteristic is unique to FHL2 early-response products, the oncoproteins Fos and Jun. FHL2 as- because all of the other members of the FHL family are not sociates with both Jun and Fos, in vitro and in vivo. The FHL2-Jun inducible. This feature prompted us to explore the possibility interaction requires the Ser-63-Ser-73 JNK phosphoacceptor sites in that FHL2 could indeed modulate the activity of the serum- c-Jun, but not their phosphorylation. -

Evolutionarily Diverse LIM Domain-Containing Proteins Bind Stressed Actin Filaments Through a Conserved Mechanism

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.06.980649; this version posted March 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Evolutionarily diverse LIM domain-containing proteins bind stressed actin filaments through a conserved mechanism Jonathan D. Winkelman1*, Caitlin A. Anderson2*, Cristian Suarez2, David R. Kovar2,3 and Margaret L. Gardel1,4 1Institute for Biophysical Dynamics, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. 2Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA 4James Franck Institute, Physics Department and Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. *Contributed equally #Correspondence should be addressed to: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.06.980649; this version posted March 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. SUMMARY The actin cytoskeleton assembles into diverse load-bearing networks including stress fibers, muscle sarcomeres, and the cytokinetic ring to both generate and sense mechanical forces. The LIM (Lin11, Isl- 1 & Mec-3) domain family is functionally diverse, but most members can associate with the actin cytoskeleton with apparent force-sensitivity. -

The Ajuba LIM Domain Protein Is a Corepressor for SNAG Domain–Mediated Repression and Participates in Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling

Research Article The Ajuba LIM Domain Protein Is a Corepressor for SNAG Domain–Mediated Repression and Participates in Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling Kasirajan Ayyanathan,1,4 Hongzhuang Peng,1 Zhaoyuan Hou,1 William J. Fredericks,1 Rakesh K. Goyal,3 Ellen M. Langer,2 Gregory D. Longmore,2 and Frank J. Rauscher III1 1The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 2Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St.Louis, Missouri; 3Blood and Marrow Transplantation Program, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 4Center for Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida Abstract with the components of the basal transcription machinery, (b) ATP-dependent remodeling of chromatin, and (c) site-specific The SNAG repression domain is comprised of a highly modifications such as acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, conserved 21–amino acid sequence, is named for its presence and ubiquitination of the nucleosomal histones, which serve as in the Snail/growth factor independence-1 class of zinc finger biochemical codes in the context of complex chromatin structure transcription factors, and is present in a variety of proto- (2).A widely accepted paradigm is that histone acetylation leads to oncogenic transcription factors and developmental regula- gene activation, whereas histone deacetylation results in repres- tors. The prototype SNAG domain containing oncogene, sion.Importantly, many repressors function through corepressor growth factor independence-1, is responsible for the develop- molecules as exemplified by DR-DRAP-1 (3), WRPW-Groucho (4), ment of T cell thymomas. The SNAIL proteins also encode the REST-Co-REST (5), and KRAB–KRAB-associated protein-1 (KAP-1; SNAG domain and play key roles in epithelial mesenchymal ref.6). -

The LIM Protein Ajuba Influences Interleukin-1-Induced NF-Κb

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2005 The IML protein Ajuba influences interleukin-1-induced NF-κB activation by affecting the assembly and activity of the protein kinase Cζ/p62/TRAF6 signaling complex Yungfeng Feng Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Gregory D. Longmore Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Feng, Yungfeng and Longmore, Gregory D., ,"The LIM protein Ajuba influences interleukin-1-induced NF-κB activation by affecting the assembly and activity of the protein kinase Cζ/p62/TRAF6 signaling complex." Molecular and Cellular Biology.25,10. 4010-4022. (2005). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/2739 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The LIM Protein Ajuba Influences Interleukin-1-Induced NF- κB Activation by Affecting the Assembly and Activity of the Protein Kinase Cζ/p62/TRAF6 Signaling Complex Downloaded from Yungfeng Feng and Gregory D. Longmore Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25(10):4010. DOI: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4010-4022.2005. http://mcb.asm.org/ Updated information and services can be found at: http://mcb.asm.org/content/25/10/4010 These include: SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL Supplemental material on January 6, 2014 by Washington University in St. Louis REFERENCES This article cites 45 articles, 23 of which can be accessed free at: http://mcb.asm.org/content/25/10/4010#ref-list-1 CONTENT ALERTS Receive: RSS Feeds, eTOCs, free email alerts (when new articles cite this article), more» Information about commercial reprint orders: http://journals.asm.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml To subscribe to to another ASM Journal go to: http://journals.asm.org/site/subscriptions/ MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR BIOLOGY, May 2005, p.