CHAPTER 6 the Quintessential Esoterism of Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

Islamic Charity) for Psychological Well-Being

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 2, 2020 Review Article UNDERSTANDING OF SIGNIFICANCE OF ZAKAT (ISLAMIC CHARITY) FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING 1Mohd Nasir Masroom, 2Wan Mohd Azam Wan Mohd Yunus, 3Miftachul Huda 1Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 2Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 3Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris Malaysia Received: 25.11.2019 Revised: 05.12.2019 Accepted: 15.01.2020 Abstract The act of worship in Islam is a form of submission and a Muslim’s manifestation of servitude to Allah SWT. Yet, it also offers certain rewards and benefits to human psychology. The purpose of this article is to explain how Zakat (Islamic charity), or the giving of alms to the poor or those in need, can help improve one’s psychological well-being. The study found that sincerity and understanding the wisdom of Zakat are the two important elements for improving psychological well-being among Muslim believers. This is because Zakat can foster many positive attitudes such sincerity, compassion, and gratitude. Moreover, Zakat can also prevent negative traits like greed, arrogance, and selfishness. Therefore, Zakat, performed with sincerity and philosophical understanding can be used as a form treatment for neurosis patients. It is hoped that this article can serve as a guideline for psychologists and counsellors in how to treat Muslim neurosis patients. Keywords: Zakat; Psychological Well-being; Muslim; Neurosis Patient © 2019 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.02.127 INTRODUCTION Zakat (Islamic charity) is one of the five pillars of Islam, made THE DEFINITION OF ZAKAT, PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING compulsory for each Muslim to contribute part of their assets AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTURBANCE or property to the rightful and qualified recipients. -

Deradicalization Model at Tariqa Pesantren in Tasikmalaya District

Deradicalization Model at Tariqa Pesantren in Tasikmalaya District Akhmad Satori1, Fitriyani Yuliawati1 and Wiwi Widiastuti1 1Department of Political Sciences, Siliwangi State University Keywords: Development Models, Tariqa Pesantren, Radicalism, Deradicalization Abstract: Research with the title of Deradicalization Model at Tariqa Pesantren in Tasikmalaya District is expected to produce works that can find the concept of nationalism and de radicalization that run on pesantren education to be implemented in other community. To be able to fully illustrate the patterns formed in religious rituals, education, teaching among Pesantren Tariqa, the research method used using the qualitative-descriptive method. The results show that there is a positive correlation between tariqa and de radicalization, reinforced by several factors, first, tariqa offers the flexibility of dialogue between religious teachings and local culture, so accepting the differences of idealism. Second, the very clear distinction in the main concept of jihad in the logic of radical fundamentalists with the adherents of the tariqa the third, the internalization of the value of Sufi values is based on the spirit of ihsan (Islamic ethics) which is the value of the universal value in life. The spirit of tariqa nationalism is rooted in the long history of the Indonesian nation, placing the interests of the state in line with the understanding of the faith. Therefore it can be concluded that the potential of de radicalization can grow and develop in Tariqa Pesantren. 1 INTRODUCTION The opening of the texts of freedom of expression in and can encourage a person to takeaction. Each the Reformationeraaffects the development of thelife educational institution has a big task to deal with this Islamic society in Indonesia. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Islam, Iman, Ihsan, Mahabatullah: the Holistic and Integrated Worldview of Islam”

“ISLAM, IMAN, IHSAN, MAHABATULLAH: THE HOLISTIC AND INTEGRATED WORLDVIEW OF ISLAM” Speech by M. Kamal Hassan, 2021 1. CRISES AND PROBLEMS IN MUSLIM SOCIETIES AS A CONSEQUENCE OF SUPERFICIAL, FRAGMENTED, PARTIALISTIC OR FAULTY UNDERSTANDING OR PERCEPTIONS OF ISLAM LEADING TO PARTIAL MANIFESTATIONS OF ISLAM IN MUSLIM SOCIETY: UNISLAMIC BUT DOMINANT CONCEPTIONS AND MODELS OF DEVELOPMENT, UNDER-DEVELOPMENT, LEAST DEVELOPED, MOST DEVELOPED, ADVANCED SOCIETIES AND COUNTRIES. OTHER MISCONCEPTIONS INCLUDE: KNOWLEDGE, WISDOM, DEVELOPMENT, PROGRESS, MODERNITY, SUCCESS, HAPPINESS, MODERATE AND FUNDAMENTALIST MUSLIMS, ISLAMISTS, SHARI`AH, Muslim countries in a big mess with captive-minded and corrupt leaders and ignorant masses. 2. THE HADIITH JIBRIIL SUMS UP THE UNITY, INTEGRATION AND WHOLISM OF THE DEEN OF ISLAM: a) ISLAAM AS BASIC REQUIREMENT OF BEING A MUSLIM (AL-MUSLIM) WITH MINIMUM RELIGIOUS OBLIGATIONS; b) IIMAAN AS FUNDAMENTAL FOUNDATION AND WORLDVIEW OF THE DEEN OF ISLAM WHICH SHAPES THE SPECIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TRUE BELIEVERS (AL-MU’MINUUN); 1 Then he (the man) said, “Inform me about Ihsan.” He (the Messenger of Allah) answered, “It is that you should serve Allah as though you could see Him, for though you cannot see Him yet (know that) He sees you.” c) IHSAAN AS THE HIGHER SPIRITUAL CONSCIOUSNESS AND CONSTANT GOD-AWARENESS OF THE TRUE BELIEVERS OR THE SINCERE SERVANTS OF ALLAH; Quotation from Hadith of Jibreel A.S. [part 111] - Quran Academy (https: //quranacademy.io. 12 May 2018) What is Ihsan? Ihsan is an extremely comprehensive term that includes all acts of goodness towards others. It encompasses dealing with others in a goodly manner, perfecting something and doing it with excellence in order to please Allah, giving your best to people around you, fulfilling your duty as a good slave to Allah and a good person to His creation and so on and so forth. -

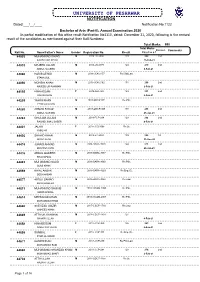

University of Peshawar

UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR NOTIFICATION Dated:___/__/____ Notification No:1122 Bachelor of Arts (Part-II), Annual Examination 2020 In partial modification of this office result Notification No1110, dated: December 31, 2020, following is the revised result of the candidates as mentioned against their Roll Numbers: Total Marks: 550 Total Marks Division Comments Roll No. Name/Father's Name Gender Registration No. Result Result w.e.f 44003 MUHAMMAD ISHAQ M 2016-LK-4886 139 284 2nd SARBILAND KHAN 15-Feb-21 44033 MAJEED ULLAH M 2015-LK-4179 124 270 2nd ABDUL MAJEED 8-Feb-21 44060 HARIS AFRIDI M 2018-JCK-2157 Re:IStd,Law, STANA GUL 44090 MOHSIN KHAN M 2018-JCK-2182 131 268 2nd NAJEEB UR RAHMAN 2-Feb-21 44195 HINA ASLAM F 2018-AGI-748 149 301 2nd ASLAM KHAN 4-Feb-21 44205 YAHYA KHAN M 2018-ODCP-971 Re:PSc, IFTIKHAR KHAN 44220 AHMAD FARAZ M 2018-ODCP-948 138 266 2nd ABDUL MASTAN 25-Jan-21 44282 GHULAM JILLANI M 2018-FCP-934 129 268 2nd RASHID JMAIL BABER 4-Feb-21 44401 JALWA F 2018-JIGC-598 Re:Ur, YAMLIHA 44436 SHAHID KHAN M 2018-FP-2983 199 355 1st NISAR KHAN 31-Dec-20 44474 JUNAID AHMAD M 2016-BARA-3028 144 273 2nd MUMTAZ KHAN 26-Jan-21 44476 ABDUL QADEER M 2017-BARA-3577 Re:PSc, KHAN AFZAL 44483 MUHAMMAD SAJID M 2016-BARA-3060 Re:PSc, OLAS KHAN 44559 KHIAL AKBAR M 2018-BARA-4029 Re:Eng (C), DEEN AKBAR 44577 ABDUL SAMAD M 2016-BARA-3062 Re:Law, KHAN HAMEED 44611 MUHAMMAD SHOAIB M 2018-II/COM-1995 Re:PSc, HAMID AFZAAL 44614 MEHMOOD KHAN M 2018-II/COM-2007 Re:PSc, MUHAMMAD KHAN 44646 SHEHZAD WAZIR M 2017-CSCP-1710 Re:Law, WAHEED KHAN 44649 ATTA UR RAHMAN M 2018-CSCP-1801 121 SHAKIR ULLAH 4-Feb-21 44658 HINA BEGUM F 2018-JICP-309 136 283 2nd BAKHTYAR KHAN 4-Feb-21 44659 SUMBAL F 2018-JICP-331 Re:Eng (C), SYED UL IBRAR 44677 GOWHER ALI M 2017-JICP-230 Re:PSc,Law, MUHAMMAD SAID 44686 MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD KHAN M 2018-JICP-294 128 274 2nd MUHAMMAD SHAFI 4-Feb-21 44704 ATTA ULLAH M 2017-QDCP-1158 Re:Ur, HAZRAT ULLAH Page 1 of 16 Total Marks Division Comments Roll No. -

Rhetoric, Philosophy and Politics in Ibn Khaldun's Critique of Sufism

Harvard Middle Eastern and Islamic Review 8 (2009), 242–291 An Arab Machiavelli? Rhetoric, Philosophy and Politics in Ibn Khaldun’s Critique of Suªsm James Winston Morris Thoughtful and informed students of Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddima (1377) are well aware that in many places his masterwork is anything but a straightforwardly objective or encyclopedic summary of the available histories and other Islamic sciences of his day. Instead, his writing throughout that unique work illustrates a highly complex, distinctive rhetoric that is constantly informed by the twofold focuses of his all- encompassing political philosophy. The ªrst and most obvious interest is discovering the essential preconditions for lastingly effective political and social organization—a task that involves far more than the outward passing forms of power. And the second is his ultimate end—the effec- tive reform of contemporary education, culture, and religion in direc- tions that would better encourage the ultimate human perfection of true scientiªc, philosophic knowing. In both of those areas, any understand- ing of Ibn Khaldun’s unique rhetoric—with its characteristic mix of multiple levels of meaning and intention expressed through irony, po- lemic satire, intentional misrepresentation and omissions, or equally un- expected inclusion and praise—necessarily presupposes an informed knowledge of the actual political, cultural, and intellectual worlds and corresponding attitudes and assumptions of various readers of his own time. It is not surprising that many modern-day students have over- looked or even misinterpreted many of the most powerful polemic ele- ments and intentions in his writing—elements that originally were often as intentionally provocative, shocking, and “politically incorrect” (in- deed frequently for very similar purposes) as the notorious writings of Nicolò Machiavelli (1536–1603) were in his time. -

The Face of Mercy: Learning the Concept and Usages of Ihsan in the Qur'an

The Face of Mercy: Learning the Concept and Usages of Ihsan in the Qur’an ALI ASADI10 Translated by Mohammad Reza Farajian Shoushtari Abstract Ihsan is among the primary and most frequently mentioned concepts in the Qur’an. Due to the wide range of its usages and semantic elements, most of its definitions in the commentaries of the Qur’an are not comprehensive or exclusive. Through an analytical-descriptive approach and with the method of interpreting the Qur’an by the Qur’an, the present research studies the concept and different examples of ihsan, its relation with other Qur’anic concepts, such as taqwa (God- wariness), faith, righteousness, reward, disbelief, denial of divine signs, oppression, and violation of the limits imposed by God. Reviewing the 10 Faculty member of Islamic Sciences and Culture Research Center. 65 Spiritual Quest Winter and Spring 2016, Vol. 6, No. 1 verses shows that the glorious Qur’an took the concept of ihsan, which was previously used in the realm of human relations, to a relatively new realm of meaning. Even though this concept has a moral color, its Qur’anic meaning and usage draw a system of interwoven and inseparable values that build up the emotional and behavioral characters of the believers in their relations with God, themselves, and others. Keywords: Ihsan, faith, righteousness, benefactors, taqwa (God-wariness) Preface As a frequent and key concept, ihsan has been widely used in the glorious Qur’an and Islamic tradition. Referring to verses and hadiths on ihsan to infer rulings in different fields of Islamic jurisprudence, such as sale, marriage, and jihad, has been widely practiced by Shia11 and Sunni12 jurists. -

Sufism in the Light of Orientalism

Sufism in the Light of Orientalism Algis Uždavinys Research Institute of Culture, Philosophy, and Arts, Vilnius This article offers a discussion of the problems regarding different interpretations of Sufism, especially those promoted by the 19th century Orientalists and modern scholars. Contrary to the prevailing opinions of those European writers who “discovered” Sufism as a kind of the Persian poetry-based mysticism, presumably unrelated to Islam, the Sufis themselves (at least before the Western cultural expansion) regarded Sufism as the inmost kernel of Islam and the way of the Prophet himself. The title of our paper is rather paradoxical and not without irony, especially bearing in mind the metaphysical connotations of the word “light” (nur in Arabic), which is used here, however, in the trivial ordinary metaphorical sense and has nothing to do with any sort of mystical illumination. It certainly does not mean that Orientalism would be regarded as a source of some supernatural light, although the “light of knowledge”, upon which the academic scholarship so prides itself, may be understood simply as one hermeneutical perspective among others, thereby establishing the entire cluster of interpretative tales, or phenomenological fictions which are nonetheless sufficiently real within their own imaginative historical, if not ontological, horizons. The scholarly term “Sufism” (with the “-ism” ending characteristic of the prestigious tableaux of modern Western ideological constructions) was introduced in the 18th century by the European scholars, those who were more or less connected to the late 18th century policies of the East India Company. It appeared in the context of certain ideological and cultural predispositions as well as highly selective and idealized expectations. -

Introduction 1 What Is Sufism? History, Characteristics, Patronage

Notes Introduction 1 . It must be noted that even if Sufism does indeed offer a positive mes- sage, this does not mean that non-Sufi Muslims, within this dichotomous framework, do not also offer similar positive messages. 2. We must also keep in mind that it is not merely current regimes that can practice illiberal democracy but also Islamist governments, which may be doing so for power, or based on their specific stance of how Islam should be implemented in society (Hamid, 2014: 25–26). 3 . L o i m e i e r ( 2 0 0 7 : 6 2 ) . 4 . Often, even cases that looked to be solely political actually had specific economic interests underlying the motivation. For example, Loimeier (2007) argues that in the cases of Sufi sheikhs such as Ahmad Khalifa Niass (b. 1946), along with Sidi Lamine Niass (b. 1951), both first seemed to speak out against colonialism. However, their actions have now “be[en] interpreted as particularly clever strategies of negotiating privileged posi- tions and access to scarce resources in a nationwide competition for state recognition as islamologues fonctionnaries ” (Loimeier, 2007: 66–67). 5 . There have been occasions on which the system was challenged, but this often occurred when goods or promises were not granted. For example, Loimeier (2007: 63) explains that the times when the relationship seemed to be questioned were times when the state was having economic issues and often could not provide the benefits people expected. When this happened, Murid Sufi leaders at times did speak out against the state’s authority (64).