Hindsight for Foresight: Lessons About Agreement Governance from Implementing the Gulf Communities Agreement (GCA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carpentaria Gulf Region

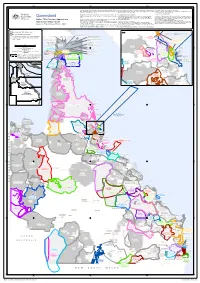

138°0'E 139°0'E 140°0'E 141°0'E 142°0'E 143°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from external boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas finalised. NNTT based on data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The being claimed) as they have been recognised by the Federal Court Currency is based on the information as held by the NNTT and may not State of Queensland for that portion where their data has been used. process. reflect all decisions of the Federal Court. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal To determine whether any areas fall within the external boundary of an Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Court, the map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the application or determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and NORTHERN Australia) 2006. Register of Native Title Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. databases is required. Further information is avaIlable from the Tribunals NORTHERN TERRITORY Carpentaria Gulf Region The applications shown on the map include: website at www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Non freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 March 2021. test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and Native Title Claimant Applications and - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being agents and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in applied, no liability and give no undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning Determination Areas 1998, all applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. -

Land and Language in Cape York Peninsula and the Gulf

Land and Language in Cape york peninsula and the Gulf Country edited by Jean-Christophe Verstraete and Diane Hafner x + 492 pp., John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2016, ISBN 9789027244543 (hbk), US$165.00. Review by Fiona Powell This volume is number 18 in the series Culture and Language Use (CLU), Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, edited by Gunter Seft of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen. It is a Festschrift for Emeritus Professor Bruce Rigsby. His contributions to anthropology during his tenure as professor at the University of Queensland from 1975 until 2000 and his contributions to native title have profoundly enriched the lives of his students, his colleagues and the Aboriginal people of Cape York. The editors and the contributors have produced a volume of significant scholarship in honour of Bruce Rigsby. As mentioned by the editors: ‘it is difficult to do justice to even the Australian part of Bruce’s work, because he has worked on such a wide range of topics and across the boundaries of disciplines’ (p. 9). The introductory chapter outlines the development of the Queensland School of Anthropology since 1975. Then follow 19 original articles contributed by 24 scholars. The articles are arranged in five sections (Reconstructions, World Views, Contacts and Contrasts, Transformations and Repatriations). At the beginning of the volume there are two general maps (Map 1 of Queensland and Map 2 of Cape York Peninsula and the Gulf Country) both showing locations mentioned in the text. There are three indexes: of places (pp. 481–82; languages, language families and groups (pp. -

Issue #3, June 2017

Issue #3, June 2017 Introducing Palm Island “We want to build a closer relationship between Queensland’s Indigenous Campbell Page have been assisting in the Communities and the Ambulance Service development of the community on Palm Island for 3 that can help us to get a better years. In that time we have seen some fantastic understanding of the health needs of stories come from the programs that we run, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander now we want to share our success stories with you. people.” – Selina As of June, we currently have 41 staff members running 10 programs for job seekers and 286 out of Both ladies believe that they can help the a possible 328 participants are attending our programs. health care system better understand the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander In Issue #3 of our newsletter read about: people by incorporating local and cultural How two Palm Island women follow their knowledge to enhance the level of service dreams and achieve their goals they provide. Ian Palmers journey The whole Palm Island community is How we acknowledged our roots and our extremely proud and cannot wait to see them tribe during Bwgcolman celebrations around the Island again in their new uniforms. The International Women’s Day lunch held on Congratulations Selina and Keita! the Island Our two new staff members, Katreena and Lucy Palm Island CDP produces new Paramedics Selina Hughes and Keita Obah-Lenoy were participants of Campbell Page’s Community Development Program activities on Palm Island – now they are both excelling in their field as Advanced Care Paramedics (ACPs). -

Radiocarbon and Linguistic Dates for Occupation of the South Wellesley Islands, Northern Australia

Archaeol. Oceania 45 (2010) 39 –43 Research Report Limited archaeological studies have been conducted in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria. on the adjacent mainland Robins et al. (1998) have reported radiocarbon dates for three sites dating between c.1200 and 200 years ago. For Radiocarbon and linguistic dates for Mornington Island in the north, Memmott et al. (2006:38, occupation of the South Wellesley 39) report dates of c.5000–5500 BP from Wurdukanhan on Islands, Northern Australia the Sandalwood River on the central north coast of Mornington Island. In the Sir Edward Pellew Group 250 km to the northwest of the Wellesleys, Sim and Wallis (2008) SEAN ULM, NICHoLAS EvANS, have documented occupation on vanderlin Island extending DANIEL RoSENDAHL, PAUL MEMMoTT from c.8000 years ago to the present with a major hiatus in and FIoNA PETCHEy occupation between 6700 and 4200 BP linked to the abandonment of the island after its creation and subsequent reoccupation. Keywords: radiocarbon dates, island colonisation, Tindale (1963) recognised the archaeological potential of Kaiadilt people, Kayardild language, Bentinck Island, the Wellesley Islands, undertaking the first excavation in the Sweers Island region at Nyinyilki on the southeast corner of Bentinck Island. A 3' x 7' (91 cm x 213 cm) pit was excavated into the crest of the high sandy ridge separating the beach from Nyinyilki Lake: Abstract The first 20 cm had shells, a ‘nara shell knife, turtle bone. At 20 cm there was a piece of red ochre of a type exactly Radiocarbon dates from three Kaiadilt Aboriginal sites on the parallel with the one which one of the women was using South Wellesley Islands, southern Gulf of Carpentaria, in the camp to dust her thigh in the preparation of rope for demonstrate occupation dating to c.1600 years ago. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

National Native Title Tribunal

NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Letter to Attorney-General 1 Table of contents 3 Introduction – President’s Report 5 Tribunal values, mission, vision 9 Corporate overview – Registrar’s Report 10 Corporate goals Goal One: Increase community and stakeholder knowledge of the Tribunal and its processes. 19 Goal Two: Promote effective participation by parties involved in native title applications. 25 Goal Three: Promote practical and innovative resolution of native title applications. 30 Goal Four: Achieve recognition as an organisation that is committed to addressing the cultural and customary concerns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 44 Goal Five: Manage the Tribunal’s human, financial, physical and information resources efficiently and effectively. 47 Goal Six: Manage the process for authorising future acts effectively. 53 Regional Overviews 59 Appendices Appendix I: Corporate Directory 82 Appendix II: Other Relevant Legislation 84 Appendix III: Publications and Papers 85 Appendix IV: Staffing 89 Appendix V: Consultants 91 Appendix VI: Freedom of Information 92 Appendix VII: Internal and External Scrutiny, Social Justice and Equity 94 Appendix VIII: Audit Report & Notes to the Financial Statements 97 Appendix IX: Glossary 119 Appendix X: Compliance index 123 Index 124 National Native Title Tribunal 3 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1324-9991 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes if an acknowledgment of the source is included. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. -

Thuwathu/Bujimulla Indigenous Protected Area

Thuwathu/Bujimulla Indigenous Protected Area MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared by the Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation on behalf of the Traditional Owners of the Wellesley Islands LARDIL KAIADILT YANGKAAL GANGALIDDA This document was funded through the Commonwealth Government’s Indigenous Protected Area program. For further information please contact: Kelly Gardner Land & Sea Regional Coordinator Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation Telephone: (07) 4745 5132 Email: [email protected] Thuwathu/Bujimulla Indigenous Protected Area Management Plan Prepared by Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation on behalf of the Traditional Owners of the Wellesley Islands Acknowledgements: This document was funded through the Commonwealth Government’s Indigenous Protected Area program. The Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation would like to acknowledge and thank the following organisations for their ongoing support for our land and sea management activities in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria: • Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Community (SEWPaC) • Queensland Government Department of Environment and Heritage Protection (EHP) • Northern Gulf Resource Management Group (NGRMG) • Southern Gulf Catchments (SGC) • MMG Century Environment Committee” Photo over page: Whitecliffs, Mornington Island. Photo courtesy of Kelly Gardner. WARNING: This document may contain the names and photographs of deceased Indigenous People. ii Acronyms: AFMA Australian Fisheries Management -

Syntactic Reconstruction by Phonology

The final version of the paper was published in R. Hendery & J. Hendriks eds, Grammatical change: theory and description. Canberra: CLRC/Pacific Linguistics. Syntactic reconstruction by phonology: Edge aligned reconstruction and its application to Tangkic truncation* Erich R. Round, Yale University 1. Introduction This chapter introduces a method for deriving historical syntactic hypotheses from certain types of phonological reconstructions. The method, EDGE ALIGNED RECONSTRUCTION, capitalises on the robust typological generalisation that the edges of high level phonological domains, such as the utterance and intonation phrase, align almost always with the edges of major syntactic domains such as the sentence and the clause (Selkirk 1984, Nespor and Vogel 1986). Essentially, because the highest levels of phonological and syntactic domains are aligned with one another, if a phonological change is reconstructed as having occurred solely at the left edge, right edge, or in the interior of a high level phonological domain, then we predict that the change will have impacted differently on words in initial, final or in medial position within the corresponding syntactic domain. That is, if words can be identified which must have * For helpful comments and discussion I would like to thank Nick Evans, Harold Koch, Mary Laughren, Pat McConvell, David Nash and Jane Simpson as well as two anonymous referees, and Stanley Insler at Yale University. Of course the views expressed here will not always accord with theirs, and all responsibility is my own. Much of this research was spurred by my fieldwork on Kayardild, encouraged by Nick Evans and Janet Fletcher and generously supported by the Hans Rausing Endangered Language Documentation Programme through grants FTG0025 and IGS0039, and particularly, by the Kaiadilt community itself. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

Indigenous Art Centre Guide: Far North Queensland

Indigenous Art Centre Guide: Far North Queensland Amanda Gabori painting at Mornington Island Art, Mornington Island (Gulf of Carpentaria). PO Box 6587, Cairns, QLD 4870 Australia (07) 4031 2741 Supporting culturally strong, best [email protected] practice Indigenous art enterprises. iaca.com.au The Indigenous Art Centre Alliance (IACA) @IACAQLD is the peak body and support agency for @iacaqld the Indigenous Art Centres of Far North Queensland. Establshed in 2011 by the @IACAqld community-based art and craft centres of the Torres Strait and Cape York Peninsula, IACA advocates for and strives to improve the viability of Indigenous arts enterprises. To meet the needs and aspirations of its members, IACA delivers various support programs and advice, providing logistical services, resources, organisational and business development including training. IACA functions as a communication and referral conduit between Art Centres and stakeholders, fostering opportunities for market, promotion, and partnerships. Erub artists with ghost net turtle. Image courtesy of Erub Arts IACA programs and events receive financial assistance from the Queensland Government through Arts Queensland’s (Torres Strait Islands). Backing Indigenous Arts initiative, from the Federal Government’s Ministry for the Arts through the Indigenous Visual Photo: Lynnette Griffiths Arts Industry Support program and the Australia Council for the Arts. IACA supports the Indigenous Art Code. Erub 3 Badu 1 9 Mua IACA Member Art Centres 4 Thursday Island 1 Badu Art Centre 2 Bana Yirriji -

Vernon Ah Kee | Kuku Yalanji/Waanyi/Yidinyji/Guugu Yimithirr People Annie Ah Sam 2008

WILMA WALKER | KUKU YALANJI PEOPLE KAKAN (BASKETS) 2002 ABOUT THE ARTWORK Wilma Walker’s baskets use traditional forms and styles of weaving to reflect on events from the artist’s own history. Walker taught herself to make these baskets by recalling childhood memories of watching women weaving them. As a child, Walker was hidden inside baskets by family members to prevent government officials removing her from her family, as was the government policy at the time. Walker has told of her story: I born up the (Mossman) Gorge on the riverbank in a gunya and police come along look for all the half-caste kids, but they hid me . my mother, we had to hide. In them baskets . and they hide me in that and give me (seed-pod rattles); lot, put in there, keep me quiet . when them police come say ‘No one here. No more kids. All gone . take ’em all away’. ABOUT THE ARTIST Wilma Walker (1929–2008) was an elder of the Kuku Yalanji people from Mossman Gorge, east Cape York. Her Aboriginal names are Ngadijina and Bambimilbirrja. She was one of the few women from her community who continued to weave baskets in the traditional way. Walker promoted her Indigenous culture, particularly by teaching weaving to the children in her community. CONCEPTS Wilma Walker’s art addresses family, race and history, with particular reference to the Stolen Generations. Walker used traditional basket-making to explore historical events, drawing attention to the impact of European settlement on Aboriginal Australians. PRIMARY Question: Why was it important to Wilma Walker to share her childhood memories by weaving baskets? GLOSSARY Activity: Think of a memory you have about your family that is Stolen Generations: ‘The Stolen Generations’ refers to children important to you. -

Native Title Information Handbook : Queensland / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

Native Title Information Handbook Queensland 2016 © Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies AIATSIS acknowledges the funding support of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. The Native Title Research Unit (NTRU) acknowledges the generous contributions of peer reviewers and welcomes suggestions and comments about the content of the Native Title Information Handbook (the Handbook). The Handbook seeks to collate publicly available information about native title and related matters. The Handbook is intended as an introductory guide only and is not intended to be, nor should it be, relied upon as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If you are aware that this publication contains any errors or omissions please contact us. Views expressed in the Handbook are not necessarily those of AIATSIS. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone 02 6261 4223 Fax 02 6249 7714 Email [email protected] Web www.aiatsis.gov.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Native title information handbook : Queensland / Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Native Title Research Unit. ISBN: 9781922102539 (ebook) Subjects: Native title (Australia)--Queensland--Handbooks, manuals, etc. Aboriginal Australians--Land tenure--Queensland. Land use--Law and legislation--Queensland. Aboriginal Australians--Queensland. Other Creators/Contributors: Australian Institute of Aboriginal