Transgender, Gender Expansive, & Non-Binary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bending the Mold: an Action Kit for Transgender Students

BENDING THE MOLD AN ACTION KIT FOR TRANSGENDER STUDENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 1. How Does Your School Measure Up? . .4 . How to Be a Transgender Ally . .5 . Your Social Change Toolkit . .6 . Preventing Violence and Bullying . 8. Securing Freedom of Gender Expression . 10. Promoting Transgender-Inclusive Policies . 12. Building Community and Fighting Invisibility . .14 . Protecting Confidentiality . .16 . Making Bathrooms & Locker Rooms Accessible . .18 . Fighting for Equality in Sports Teams . 20. Accessing Health Care . 22. Glossary . 24. Resources . 26. Appendix: Sample Model School Policy . .30 . A joint publication by Lambda Legal and the National Youth Advocacy Coalition (NYAC) Dedicated to Lawrence King, 1993-2008, whose memory inspires us to keep building a world in which gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and gender non-conforming youth can live freely and without fear. BENDING THE MOLD AN ACTION KIT FOR TRANSGENDER STUDENTS Transgender and gender-nonconform- students is an ever-present danger. ing students come out every day all The February 12, 2008 shooting of A May 2007 Gallup poll found that over the country, and they deserve to Lawrence King, a gender-nonconforming 68 percent of people are in favor of be treated with respect and fairness. junior high school student in Oxnard, expanding federal hate crimes laws Some schools are already supportive of California, was a tragic reminder of the to cover sexual orientation, gender gay, lesbian and bisexual students, but hate and fear that still haunt us. and gender identity. need more education around transgen- In Focus: Hate Crimes, Gay & Lesbian Alliance der issues. Other schools discourage Whether you’re transgender or Against Defamation, www.glaad.org diversity in both sexual orientation and gender-nonconforming, questioning or gender identity, and suppress or punish an ally, this kit is designed to help you The total number of victims certain forms of gender expression. -

The Flourishing of Transgender Studies

BOOK REVIEW The Flourishing of Transgender Studies REGINA KUNZEL Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies Edited by A. Finn Enke Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012. 260 pp. ‘‘Transgender France’’ Edited by Todd W. Reeser Special issue, L’Espirit Createur 53, no. 1 (2013). 172 pp. ‘‘Race and Transgender’’ Edited by Matt Richardson and Leisa Meyer Special issue, Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (2011). 147 pp. The Transgender Studies Reader 2 Edited by Susan Stryker and Aren Z. Aizura New York: Routledge, 2013. 694 pp. For the past decade or so, ‘‘emergent’’ has often appeared alongside ‘‘transgender studies’’ to describe a growing scholarly field. As of 2014, transgender studies can boast several conferences, a number of edited collections and thematic journal issues, courses in some college curricula, and—with this inaugural issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly—an academic journal with a premier university press. But while the scholarly trope of emergence conjures the cutting edge, it can also be an infantilizing temporality that communicates (and con- tributes to) perpetual marginalization. An emergent field is always on the verge of becoming, but it may never arrive. The recent publication of several new edited collections and special issues of journals dedicated to transgender studies makes manifest the arrival of a vibrant, TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly * Volume 1, Numbers 1–2 * May 2014 285 DOI 10.1215/23289252-2399461 ª 2014 Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/tsq/article-pdf/1/1-2/285/485795/285.pdf by guest on 02 October 2021 286 TSQ * Transgender Studies Quarterly diverse, and flourishing interdisciplinary field. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

Transgender Representation on American Narrative Television from 2004-2014

TRANSJACKING TELEVISION: TRANSGENDER REPRESENTATION ON AMERICAN NARRATIVE TELEVISION FROM 2004-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Kelly K. Ryan May 2021 Examining Committee Members: Jan Fernback, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Ron Becker, External Member, Miami University ABSTRACT This study considers the case of representation of transgender people and issues on American fictional television from 2004 to 2014, a period which represents a steady surge in transgender television characters relative to what came before, and prefigures a more recent burgeoning of transgender characters since 2014. The study thus positions the period of analysis as an historical period in the changing representation of transgender characters. A discourse analysis is employed that not only assesses the way that transgender characters have been represented, but contextualizes American fictional television depictions of transgender people within the broader sociopolitical landscape in which those depictions have emerged and which they likely inform. Television representations and the social milieu in which they are situated are considered as parallel, mutually informing discourses, including the ways in which those representations have been engaged discursively through reviews, news coverage and, in some cases, blogs. ii To Desmond, Oonagh and Eamonn For everything. And to my mother, Elaine Keisling, Who would have read the whole thing. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the research and writing of this dissertation, I have received a great deal of support and assistance, and therefore offer many thanks. To my Dissertation Chair, Jan Fernback, whose feedback on my writing and continued support and encouragement were invaluable to the completion of this project. -

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

Harsh Realities: the Experiences of Transgender Youth in Our Nation’S Schools

Harsh Realities The Experiences of Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools A Report from the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network www.glsen.org Harsh Realities The Experiences of Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools by Emily A. Greytak, M.S.Ed. Joseph G. Kosciw, Ph.D. Elizabeth M. Diaz National Headquarters 90 Broad Street, 2nd floor New York, NY 10004 Ph: 212-727-0135 Fax: 212-727-0254 DC Policy Office 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1105 Washington, DC 20005 Ph: 202-347-7780 Fax: 202-347-7781 [email protected] www.glsen.org © 2009 Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network ISBN 1-934092-06-4 When referencing this document, we recommend the following citation: Greytak, E. A., Kosciw, J. G., and Diaz, E. M. (2009). Harsh Realities: The Experiences of Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. New York: GLSEN. The Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network is the leading national education organization focused on ensuring safe schools for all lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students. Established nationally in 1995, GLSEN envisions a world in which every child learns to respect and accept all people, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity/expression. Cover photography: Kevin Dooley under Creative Commons license www.flickr.com/photos/pagedooley/2418019609/ Inside photography: Ilene Perlman Inside photographs are of past and present members of GLSEN’s National Student Leadership Team. The Team is comprised of a diverse group students across the United States; students in the photographs may or may not identify as transgender. Graphic design: Adam Fredericks Electronic versions of this report and all other GLSEN research reports are available at www.glsen. -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Brookings Africa Research Fellows Application

Foreign Policy Pre-Doctoral Research Fellowship Program Application How to Apply: Interested candidates should submit the following: • Application questionnaire and research project proposal; • One publication or writing sample of 10 pages or less (excerpts of larger works acceptable) in PDF format; • Official or unofficial transcript from graduate institution (course names, professor names, grades received) in PDF format; and • One email message containing all required application attachments is highly preferred, with “PreDoc Application – [Last Name, First Name]” in the subject line. • In addition, three confidential letters of recommendation must be submitted to Brookings directly by referees. Instructions are included at the bottom of this document. Application Deadlines: • Applicants must submit a complete application package to [email protected] no later than January 31, 2016 in order to be considered as a candidate. • Letters of reference must be submitted to [email protected] no later than February 15, 2016. Please Note: • Materials sent through regular postal service will not be accepted. • Incomplete applications and those received after the deadline will not be considered. - continued - 1 Personal Information Full Legal Name (as it appears on your passport):____________________________________________________ Preferred name (or nickname):______________________________________________________ Current position/title: _________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ -

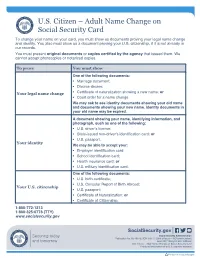

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. INCLUSIVE STORIES Although scholars of LGBTQ history have generally been inclusive of women, the working classes, and gender-nonconforming people, the narrative that is found in mainstream media and that many people think of when they think of LGBTQ history is overwhelmingly white, middle-class, male, and has been focused on urban communities. While these are important histories, they do not present a full picture of LGBTQ history. To include other communities, we asked the authors to look beyond the more well-known stories. Inclusion within each chapter, however, isn’t enough to describe the geographic, economic, legal, and other cultural factors that shaped these diverse histories. Therefore, we commissioned chapters providing broad historical contexts for two spirit, transgender, Latino/a, African American Pacific Islander, and bisexual communities. -

Police Department Model Policy on Interactions with Transgender People

POLICE DEPARTMENT MODEL POLICY ON INTERACTIONS WITH TRANSGENDER PEOPLE National Center for TRANSGENDER EQUALITY This model policy document reflects national best policies and practices for police officers’ interactions with transgender people. The majority of these policies were originally developed by the National LGBT/HIV Criminal Justice Working Group along with a broader set of model policies addressing issues including police sexual misconduct and issues faced by people living with HIV. Specific areas of the original model policy were updated and modified for use as the foundation for NCTE’s publication “Failing to Protect and Serve: Police Department Policies Towards Transgender People,” which also evaluates the policies of the largest 25 police departments in the U.S. This publication contains model language for police department policies, as well as other criteria about policies that should be met for police departments that seek to implement best practices. The larger Working Group’s model policies developed by Andrea J. Ritchie and the National LGBTQ/HIV Criminal Justice Working Group, a coalition of nearly 40 organizations including NCTE, can be found in the appendices of the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) “Gender, Sexuality, and 21st Century Policing” report. While these are presented as model policies, they should be adapted by police departments in collaboration with local transgender leaders to better serve their community. For assistance in policy development and review, please contact Racial and Economic Justice Policy Advocate, Mateo De La Torre, at [email protected] or 202-804-6045, or [email protected] or 202-642-4542. NCTE does not charge for these services.