Allkins 1 Alisa Allkins Wayne State University William Carlos Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pastoral Modernism: an American Poetics

Pastoral Modernism: An American Poetics Jennifer Tai-Chen Chang Washington, DC M.F.A., University of Virginia, 2002 B.A. University of Chicago, 1998 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Language and Literature University of Virginia May, 2017 Committee: Jahan Ramazani, Director Michael Levenson, Reader Elizabeth Fowler, Reader Claire Lyu, External Reader PASTORAL MODERNISM: AN AMERICAN POETICS TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract……………………………………………………………………………....i Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………...iii Introduction ………………………………………………………………………....1 1. William Carlos Williams and the Democratic Invitation of Pastoral………………26 2. Pastoral and the Problem of Place in Claude McKay’s Harlem Shadows……………73 3. The Pisan Cantos an the Modernity of Pastoral: Discourse, Locality, Race…………115 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………...160 ABSTRACT Pastoral Modernism: An American Poetics uncovers the re-emergence of an ancient literary mode as a vehicle for both poetic innovation and cultural investigation in three exemplary America modernist poets: William Carlos Williams, Claude McKay, and Ezra Pound. In the first half of the twentieth century, the United States experienced dramatic demographic changes due to global migration, immigration, and the Great Migration, which effectively relocated black life from the country to the city. Further, the expansion of cities, as physical locations and cultural centers, not only diminished their distance from the -

Lerud Dissertation May 2017

ANTAGONISTIC COOPERATION: PROSE IN AMERICAN POETRY by ELIZABETH J. LERUD A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of English and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Elizabeth J. LeRud Title: Antagonistic Cooperation: Prose in American Poetry This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the English Department by: Karen J. Ford Chair Forest Pyle Core Member William Rossi Core Member Geri Doran Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017. ii © 2017 Elizabeth J. LeRud iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Elizabeth J. LeRud Doctor of Philosophy Department of English June 2017 Title: Antagonistic Cooperation: Prose in American Poetry Poets and critics have long agreed that any perceived differences between poetry and prose are not essential to those modes: both are comprised of words, both may be arranged typographically in various ways—in lines, in paragraphs of sentences, or otherwise—and both draw freely from the complete range of literary styles and tools, like rhythm, sound patterning, focalization, figures, imagery, narration, or address. Yet still, in modern American literature, poetry and prose remain entrenched as a binary, one just as likely to be invoked as fact by writers and scholars as by casual readers. I argue that this binary is not only prevalent but also productive for modern notions of poetry, the root of many formal innovations of the past two centuries, like the prose poem and free verse. -

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts Group Session Panels Content Computational Comparative Literature

ICLA 2016 – Abstracts Group Session Panels, July 17th, 2016 ICLA 2016 – Abstracts Group Session Panels Content Computational Comparative Literature. Corpus-based Methodologies ................................................. 5 16082 - Assia Djebar et la transgression des limites linguistiques, littéraires et culturelles .................. 7 16284 - Pictures for Everybody! Postcards and Literature/ Bilder für alle! Postkarten und Literatur . 11 16309 - Talking About Literature, Scientifically..................................................................................... 14 16377 - Sprache & Rache ...................................................................................................................... 16 16416 - Translational Literature - Theory, History, Perspectives .......................................................... 18 16445 - Langage scientifique, langage littéraire : quelles médiations ? ............................................... 24 16447 - PANEL Digital Humanities in Comparative Literature, World Literature(s), and Comparative Cultural Studies ..................................................................................................................................... 26 16460 - Kolonialismus, Globalisierung(en) und (Neue) Weltliteratur ................................................... 31 16499 - Science et littérature : une question de langage? ................................................................... 40 16603 - Rhizomorphe Identität? Motivgeschichte und kulturelles Gedächtnis im -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

Orpheu Et Al. Modernism, Women, and the War

Orpheu et al. Modernism, Women, and the War M. Irene Ramalho-Santos* Keywords Little magazines, Poetry, Modernism, The Great War, Society, Sexual mores. Abstract The article takes off from Orpheu, the little magazine at the origin of Portuguese modernism, to reflect, from a comparative perspective, on the development of modernist poetry in the context of the Great War and the social changes evolving during the first decades of the twentieth century on both sides of the Atlantic. Palavras-chave “Little magazines,” Poesia, Modernismo, A Grande Guerra, Sociedade, Costumes sexuais. Resumo O artigo parte de Orpheu, a revista que dá origem ao modernismo português, para reflectir, numa perspectiva comparada, soBre o desenvolvimento da poesia modernista no contexto da Grande Guerra e das mudanças sociais emergentes nas primeiras décadas do século XX dos dois lados do Atlântico. * Universidade de CoimBra; University of Wisconsin-Madison. Ramalho Santos Orpheu et al. It is frequently repeated in the relevant scholarship that Western literary and artistic modernism started in little magazines.1 The useful online Modernist Journals Project (Brown University / Tulsa University), dealing so far only with American and British magazines, uses as its epigraph the much quoted phrase: “modernism began in the magazines”, see SCHOLES and WULFMAN (2010) and BROOKER and THACKER (2009-2013). With two issues published in 1915 and a third one stopped that same year in the galley proofs for lack of funding, the Portuguese little magazine Orpheu inaugurated modernism in Portugal pretty much at the same time as all the other major little magazines in Europe and the United States. This is interesting, given the proverbial belatedness of Portuguese accomplishments, and no less interesting the fact that, like everywhere else, Orpheu was followed, in Portugal as well, By a number of other little magazines. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

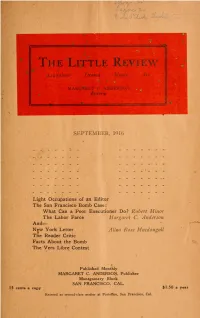

The Little Review, Vol. 3, No. 6

THE LITTLE REVIEW LITERATURE DRAMA MUSIC ART Margaret C. Anderson Editor SEPTEMBER, 1916 Light Occupations of an Editor The San Francisco Bomb Case: What Can a Poor Executioner Do? Robert Minor The Labor Farce Margaret C. Anderson And— New York Letter Allan Ross Macdougall The Reader Critic Facts About the Bomb The Vers Libre Contest Published Monthly MARGARET C. ANDERSON, Publisher Montgomery Block SAN FRANCISCO, CAL. 15 cents a copy $1.50 a year Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, San Francisco. Cal. The Vers Libre Contest The poems published in the Vers Libre Contest are now being considered by the judges. There were two hundred and two poems, thirty-two. of which were re- turned because they were either Shakespearean sonnets or rhymed quatrains or couplets. Manuscripts will be returned as promptly as they are rejected, providing the contestants sent postage. We hope to announce the results in our October issue, and publish the prize poems. —The Contest Editor. IN BOOKS Anything that's Radical MAY be found at McDevitt's Book Omnorium » 1346 Fillmore Street and 2079 Sutter Street San Francisco, California (He Sells The Little Review, Too) THE LITTLE REVIEW VOL III. SEPTEMBER, 1916 NO. 6 The Little Review hopes to become a magazine of Art. The September issue is offered as a Want Ad. Copyright, 1916, by Margaret C. Anderson 2 The Little Reviev . "The other pages will be left blank." The Little Review 3 The Little Review 4 The Little Review 5 The Little Review 6 The Little Review 7 The Little Review 8 The Little Review 9 The Little Review 10 The Little Review 11 The Little Review 14 The Little Review 13 14 The Little Review SHE PRACTICES EIGHTEEN HOURS A DAY AND- BREAKFASTING CONVERTING THE SHERIFF TO ANARCHISM AND VERS LIBRE - TAKES HER MASON AND HAMLIN TO BED WITH HER SUFFERING FOR HUMANITY AT EMMA GOLDMAN'S LECTURES Light occupations of the editor The Little Review 15 GATHERING HER OWN FIRE-WOOO THE STEED on WHICH SHE HAS SWIMMING HER PICTURE TAKEN THE INSECT ON WHICH SHE RIDES while there is nothing to edit. -

The Little Review and Modernist Salon Culture

MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER "Conversations That Fly": The Little Review and Modernist Salon Culture RON LEVY -, Supervisor: Dr. Irene Gammel Reader: Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada January 2010 Levy 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Irene Gammel for introducing me, through her course CC8938: Modernist Literary Circles: A Cultural Approach, to the Little Review. The personalities that populated the pages of this historically important literary journal practically leapt off the page and attracted me to learn more. Dr. Gammel's enthusiastic and patient guidance made it possible for me to learn about a subject that greatly interests me- the power oftalk - and to challenge myself to reach new levels of research and writing. Unexpectedly, this project also helped me to learn about myself. I found many similarities between my experiences communicating and debating sometimes unpopular beliefs and those of Margaret Anderson, one of the central subjects of this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Podnieks for providing helpful and detailed feedback at short notice, all of which have found their way into this MRP and have further improved this project, as well as for introducing me, through her course CC30: Writing the Self, Reading the Lifo, to theories that relate to the autobiographical genre. Finally, I would like to thank the Joint Graduate Program in Communication and Culture for giving me this incredible experience to step into so many new worlds of thinking. -

Writing Communities: Aesthetics, Politics, and Late Modernist Literary Consolidation

WRITING COMMUNITIES: AESTHETICS, POLITICS, AND LATE MODERNIST LITERARY CONSOLIDATION by Elspeth Egerton Healey A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson, Chair Associate Professor Kali A. K. Israel Associate Professor Joshua L. Miller Assistant Professor Andrea Patricia Zemgulys © Elspeth Egerton Healey _____________________________________________________________________________ 2008 Acknowledgements I have been incredibly fortunate throughout my graduate career to work closely with the amazing faculty of the University of Michigan Department of English. I am grateful to Marjorie Levinson, Martha Vicinus, and George Bornstein for their inspiring courses and probing questions, all of which were integral in setting this project in motion. The members of my dissertation committee have been phenomenal in their willingness to give of their time and advice. Kali Israel’s expertise in the constructed representations of (auto)biographical genres has proven an invaluable asset, as has her enthusiasm and her historian’s eye for detail. Beginning with her early mentorship in the Modernisms Reading Group, Andrea Zemgulys has offered a compelling model of both nuanced scholarship and intellectual generosity. Joshua Miller’s amazing ability to extract the radiant gist from still inchoate thought has meant that I always left our meetings with a renewed sense of purpose. I owe the greatest debt of gratitude to my dissertation chair, John Whittier-Ferguson. His incisive readings, astute guidance, and ready laugh have helped to sustain this project from beginning to end. The life of a graduate student can sometimes be measured by bowls of ramen noodles and hours of grading. -

The Cultural Politics of William Carlos Williams's Poetry by Ciarán O'rourke

The Cultural Politics of William Carlos Williams's Poetry by Ciarán O'Rourke A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy University of Dublin Trinity College 2019 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University's open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Ciarán O'Rourke. Summary This thesis offers a political reading of William Carlos Williams's poetry. Grounding its analysis in the work of a range of authors and theorists, as well as his own biography and writings, it approaches Williams's poems as critical texts that in complex ways represent, reinvent, and call into question the societal life and social spaces to which they refer. This approach exemplifies a new framework for understanding Williams's work and literary evolution: one that is as historically attuned as it is aesthetically exploratory. As such, this thesis also assesses Williams's engagement with genre and poetic form, arguing that these last are closely related to his understanding of American democracy, political commentary, and radical commitment – as detailed in the opening chapter. The second chapter examines the political aesthetic that Williams establishes in his work from 1913 to 1939, highlighting the often subtle – sometimes problematic -

Depictions of Environmental Crisis in William Carlos Williams's Paterson

Depictions of Environmental Crisis in William Carlos Williams’s Paterson Sarah Nolan University of Nevada, Reno ~ [email protected] Abstract Reading the environmental crises in William Carlos Williams’s Paterson allegorically allows us to recognize present day environmental concerns more readily and highlights the losses that lie ahead if we continue to ignore environmental threats. Williams’s ecopoetics throughout Paterson, which imaginatively depicts the effects of environmental disasters within the language and form of the poem, shows us the consequences of inaction and the true threat that disaster poses. This poetic example of the consequences of inaction holds particular power because it presents a material experience for all readers and a potentially allegorical poetic experience for the historically situated reader. Paterson shows us that waiting for disaster to force the world “to begin to begin again,” is an unsustainable model for the planet’s future (Williams, 1963, p. 140). By recognizing that this text provides a unique allegorical experience for the historically situated reader and acknowledging the significance of such a message, we can become more aware of the problems that we face now and their potential directions in coming decades. Presented at Bridging Divides: Spaces of Scholarship and Practice in Environmental Communication The Conference on Communication and Environment, Boulder, Colorado, June 11-14, 2015 https://theieca.org/coce2015 Page 2 of 7 In his 2002 book Greening the Lyre: Environmental Poetics and Ethics, David Gilcrest argues that our attitudes toward the natural environment will only change as a result of “environmental crisis” (p. 22). Although this prediction is apt, as evidenced by the rise of resistance movements to environmental recovery agendas over the past two decades, it implies that such environmental crisis must physically devastate the Earth before action will be taken.i Such a model of apocalyptic environmental activism, however, has proven to be ineffective. -

Modernism and the Periodical Scene in 1915 and Today

Modernism and the Periodical Scene in 1915 and Today Andrew Thacker* Keywords Pessoa, Modernism, Magazines, Orpheu, Periodization. Abstract This article considers the Portuguese magazine Orpheu (1915) within the wider context of periodicals within modernism, drawing upon work carried out by the Modernist Magazines Project. It does this by considering such crucial features of the modernist magazine as its chronology and its geographical reach, and also points to new methods of analysing the materiality of magazines. By understanding the broader milieu of the modernist magazine we gain a clearer sense of how Orpheu can begin to be placed within the cultural field of the modernism. Palavras-chave Pessoa, Modernismo, Revistas, Orpheu, Periodização. Resumo Este artigo considera a revista portuguesa Orpheu (1915) no contexto mais alargado dos periódicos no âmbito do modernismo, baseando-se em trabalho desenvolvido ao abrigo do projeto de investigação Modernist Magazines Project. Fá-lo, considerando aspetos cruciais da revista modernista tais como a sua cronologia e a sua abrangência geográfica, propondo além disso novos métodos de análise da materialidade da revista. Ao compreendermos o meio mais alargado da revista modernista, ganhamos uma visão mais clara do posicionamento de Orpheu no campo cultural do modernismo. * Department of English, Nottingham Trent University Thacker Modernism and the Periodical Scene Orpheu is a significant example of the modernist “little magazine,” a phenomenon with a complex history and multiple iterations across