ADDRESS: 5700 N BROAD ST Name of Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options

Advocacy Sustainability Partnerships Fort Washington Office Park Transportation Demand Management Plan Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options Prepared by GVF GVF July 2017 Contents Executive Summary and Key Findings ........................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Sources ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 ArcMap Geocoding and Data Analysis .................................................................................................. 6 Travel Times Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 7 Data Collection .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Employee Commuter Survey Results ................................................................................................ 7 2. Office Park Companies Outreach Results ......................................................................................... 7 3. Office Park -

Regional Rail

STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES * SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS and MAJOR HOLIDAYS PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TERMINALS E and F 37, 108, 115 )DUH 6HUYLFHV 7UDLQ1XPEHU AIRPORT INFORMATION AIRPORT TERMINALS C and D 37, 108, 115 =RQH Ê*Ë6WDWLRQV $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 $0 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 $0 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV( ) TERMINAL A - EAST and WEST AIRPORT TERMINAL B 37, 108, 115 REGIONAL RAIL AIRPORT $LUSRUW7HUPLQDOV& ' D American Airlines International & Caribbean AIRPORT TERMINAL A EAST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO% British Airways AIRPORT TERMINAL A WEST 37, 108, 115 D $LUSRUW7HUPLQDO$ LINE EASTWICK (DVWZLFN Qatar Airways 37, 68, 108, 115 To/From Center City Philadelphia D 8511 Bartram Ave & D 3HQQ0HGLFLQH6WDWLRQ Eastern Airlines PENN MEDICINE STATION & DDWK6WUHHW6WDWLRQ ' TERMINAL B 3149 Convention Blvd 40, LUCY & DD6XEXUEDQ6WDWLRQ ' 215-580-6565 Effective September 5, 2021 & DD-HIIHUVRQ6WDWLRQ ' American Airlines Domestic & Canadian service MFL, 9, 10, 11, 13, 30, 31, 34, 36, 30th STREET STATION & D7HPSOH8QLYHUVLW\ The Philadelphia Marketplace 44, 49, 62, 78, 124, 125, LUCY, 30th & Market Sts Amtrak, NJT Atlantic City Rail Line • Airport Terminals E and F D :D\QH-XQFWLRQ ² ²² ²² ²² ² ² ² Airport Marriott Hotel SUBURBAN STATION MFL, BSL, 2, 4, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, DD)HUQ5RFN7& ² 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 48, 62, • Airport Terminals C and D 16th St -

Atglen Station Concept Plan

Atglen Station Concept Plan PREPARED FOR: PREPARED BY: Chester County Planning Commission Urban Engineers, Inc. June 2012 601 Westtown Road, Suite 270 530 Walnut Street, 14th Floor ® Chester County Planning Commission West Chester, PA 19380 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Acknowledgements This plan was prepared as a collaboration between the Chester County Planning Commission and Urban Engineers, Inc. Support in developing the plan was provided by an active group of stakeholders. The Project Team would like to thank the following members of the Steering Advisory and Technical Review Committees for their contributions to the Atglen Station Concept Plan: Marilyn Jamison Amtrak Ken Hanson Amtrak Stan Slater Amtrak Gail Murphy Atglen Borough Larry Lavenberg Atglen Borough Joseph Hacker DVRPC Bob Garrett PennDOT Byron Comati SEPTA Harry Garforth SEPTA Bob Lund SEPTA Barry Edwards West Sadsbury Township Frank Haas West Sadsbury Township 2 - Acknowledgements June 2012 Atglen Station Concept Plan Table of Contents Introduction 5 1. History & Background 6 2. Study Area Profi le 14 3. Station Site Profi le 26 4. Ridership & Parking Analysis 36 5. Rail Operations Analysis 38 6. Station Concept Plan 44 7. Preliminary Cost Estimates 52 Appendix A: Traffi c Count Data 54 Appendix B: Ridership Methodology 56 Chester County Planning Commission June 2012 Table of Contents - 3 4 - Introduction June 2012 Atglen Station Concept Plan Introduction The planning, design, and construction of a new passenger rail station in Atglen Borough, Chester County is one part of an initiative to extend SEPTA commuter service on the Paoli-Thorndale line approximately 12 miles west of its current terminus in Thorndale, Caln Township. -

Directions to Lincoln Financial Field Via Public Transportation One Lincoln Financial Field Way Philadelphia, PA

Directions to Lincoln Financial Field Via Public Transportation One Lincoln Financial Field Way Philadelphia, PA The quickest way to Lincoln Financial Field is south along the SEPTA Broad Street Subway Line. Exit at the last southbound stop, AT&T Station. From Center City, North Philadelphia, South Philadelphia Take the SEPTA Broad Street Subway Line south to AT&T Station. South Philadelphia alternative: Route C bus southbound to Broad Street. From West Philadelphia Take the Market-Frankford Line east to 15th Street Station, transfer to the Broad Street Line southbound to AT&T Station (no charge for transfer at 15th street). From Suburbs - via train Take Regional Rail train to Suburban Station (16th & JFK), walk through concourse to City Hall Station, transfer to Broad Street Line southbound to AT&T Station. From Nearby Western Suburbs - via bus or trolley Take a suburban bus or trolley route to 69th Street Terminal, transfer to eastbound Market-Frankford Line, ride to 15th Street Station, transfer to Broad Street Line southbound to AT&T Station. From PATCO High-Speed Line (originating in Lindenwold, NJ) Take PATCO High-Speed line west to 12th/13th Walnut Street Station, connect with SEPTA Broad Street Line southbound at Walnut-Locust Station. Exit Broad Street Line at AT&T Station. Ask cashier at PATCO Station for round-trip ticket that's good for fare on both PATCO and the Broad Street Line. Last Subway Trains Following Night Games SEPTA Broad Street Line subway trains are scheduled to depart from Pattison Avenue shortly after our games end. If a game continues past midnight, shuttle buses operating on Broad Street will replace subway trains. -

Mtairy Apr2008 Web.Pdf

3 9 19 29 41 57 71 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Mt. Airy USA Stakeholder Interviews Elizabeth Moselle, Th e Avenue Project - Program Manager, Project Lead Tyson Boles, Germantown Avenue Homeowner Cicely Peterson-Mangum, Th e Avenue Project - Director David Fellner, Commercial Property-Owner Farah Jimenez, Executive Director Sheila Green, Germantown Avenue Business-Owner John Kahler & Th eresa Youngblut, Lutheran Th eological Seminary Steering Committee La-Shainnia Peaker & Paul Sachs, Northwest Human Services Phillip Seitz, Cliveden of the National Trust Jennifer Barr, Philadelphia City Planning Commission Mary Small, Sacred Heart Manor Susan Bushu, Commercial Property-Owner Marilyn Wells, Century 21 Wells Real Estate Jocie Dye,* Infusion Coff ee & Tea Gallery David Fellner,* Commercial Property-Owner Brenda Foster,* Au Revoir Travel Consultant Team Elan Gepner, Building Blocks, Germantown Community Th eater Project Brown & Keener Bressi, Lead Consultant Andrew Gerson,* Building Blocks, Germantown Community Th eater Project Lager Raabe Skaft e Landscape Architects Judie Gilmore, Mural Arts Program Pennoni Associates Inc. Jason Huber,* Infusion Coff ee & Tea Gallery Cloud Gehshan Associates Carolyn Johnson* Yvonne McCalla, Mt. Airy USA & Freelance Artist Additional Acknowledgements Dan Muroff ,* Mt. Airy USA Board Member & EMAN President Steven Preiss,* Steven Preiss Design We are grateful to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) for Kurt Raymond,* CICADA Architects awarding us with the funding and dedicated staff support that made the successful David Schaaf,* Philadelphia City Planning Commission development of this plan possible. Our deepest appreciation is extended to Carolyn Wallis, Nicole Seitz, Society Created to Reduce Urban Blight (S.C.R.U.B.) formerly of the PA Environmental Council and Patrick Starr of the PA Environmental Shirley Simmons, Mayor’s Business Action Team (MBAT) Council who, thanks to the William Penn Foundation, developed the original concept Lisa Salley,* Heritage Capital and proposal for this project. -

R Egion a L R a Il

Airport Line Public Timetable expanded 2_Layout 10 5/17/2016 9:05 AM Page 1 PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS AND MAJOR HOLIDAYS AIRPORT INFORMATION STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES * Fare Services Train Number 4802* 404 4704 406 4708 410 4712 414 4716 418 4720 422 4724 426 4728 430 4732 434 4736 438 4740 442 4744 446 4748 450 4752 454 4756 458 4760 462 4764 466 4768 468 472 476 478 AIRPORT TERMINALS E and F 37, 108, 115 Ê * Ë Zone Stations AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMAM TERMINAL A - EAST and WEST 4 D Airport Terminals E & F 5:07 5:37 6:07 6:37 7:07 7:37 8:07 8:37 9:07 9:37 10:07 10:37 11:07 11:37 12:07 12:37 1:07 1:37 2:07 2:37 3:07 3:37 4:07 4:37 5:07 5:37 6:07 6:37 7:07 7:37 8:07 8:37 9:07 9:37 10:07 10:37 11:07 11:37 12:07 AIRPORT TERMINALS C and D 37, 108, 115 4 D Airport Terminals C & D 5:09 5:39 6:09 6:39 7:09 7:39 8:09 8:39 9:09 9:39 10:09 10:39 11:09 11:39 12:09 12:39 1:09 1:39 2:09 2:39 3:09 3:39 4:09 4:39 5:09 5:39 6:09 6:39 7:09 7:39 8:09 8:39 9:09 9:39 10:09 10:39 11:09 11:39 12:09 RAIL REGIONAL AIRPORT 4 D Airport Terminal B 5:10 5:40 6:10 6:40 7:10 7:40 8:10 8:40 9:10 9:40 10:10 10:40 11:10 11:40 12:10 12:40 1:10 1:40 2:10 2:40 3:10 3:40 4:10 4:40 5:10 5:40 6:10 6:40 7:10 7:40 8:10 8:40 9:10 9:40 10:10 10:40 11:10 11:40 12:10 American Airlines International & Caribbean (includes all AIRPORT TERMINAL B 37, 108, 115 4 D Airport Terminal A 5:11 5:41 6:11 6:41 7:11 7:41 8:11 8:41 9:11 9:41 10:11 10:41 11:11 11:41 12:11 12:41 1:11 1:41 2:11 2:41 3:11 -

Radnor Station Connectivity 2 Figure A: Map of Study Area Recommendations

December 2017 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 Project Overview and Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 6 Previous Recommendations ............................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 2: Existing Conditions .................................................................................................. 9 Transit Options in Radnor .................................................................................................................................. 10 Parking and Shuttles ......................................................................................................................................... 16 Roadway and Walking Conditions ..................................................................................................................... 18 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................ 19 Chapter 3: Transfer Demand Assessment .............................................................................. 21 Existing Transfers ............................................................................................................................................. -

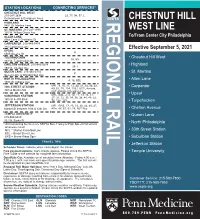

Chestnut Hill West Line

STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES* CHESTNUT HILL WEST 215-247-3834 23, 77, 94, 97, L Germantown & Evergreen Aves CHESTNUT HILL HIGHLAND REGIONAL RAIL 8452 St. Martins Lane ST. MARTINS 215-247-1999 WEST LINE 320 W. Willow Grove Ave ALLEN LANE To/From Center City Philadelphia Allen Lane & Cresheim St CARPENTER 215-849-7474 310 Carpenter Lane Effective September 5, 2021 UPSAL H 6505 Greene St TULPEHOCKEN • Chestnut Hill West 53, 65 333 W. Tulpehocken St CHELTEN AVENUE 215-843-5614 26, J • Highland 359 W. Chelten Ave QUEEN LANE 215-844-3174 K • St. Martins Queen Lane & Wissahickon Ave NORTH PHILADELPHIA 4, 16, BSL • Allen Lane 1503 W. Indiana Ave 30th STREET STATION MFL, 9, 10, 11, 13, 30, 31, 34, 36, 44, • Carpenter 49, 62, 78, 124, 125, LUCY, Amtrak, 30th & Market Sts NJT Atlantic City Rail Line • Upsal SUBURBAN STATION MFL, BSL, 2, 4, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 38, 44, 48, 62, 16th St & JFK Blvd 78, 124, 125 • Tulpehocken JEFFERSON STATION MFL, BRS, 17, 23, 33, 38, 44, 45, 47, Market St between 10th & 12th Sts 47m, 48, 61, 62, 78, NJT Bus • Chelten Avenue TEMPLE UNIVERSITY • Queen Lane 215-580-5440 927 W. Berks St * All Connecting Services are SEPTA Bus, Trolley or High Speed Rail unless • North Philadelphia otherwise noted MFL = Market-Frankford Line • 30th Street Station BSL = Broad Street Line BRS = Broad-Ridge Spur • Suburban Station TRAVEL TIPS • Jefferson Station Schedule Times: Indicate when trains depart the station Fare payment options: cash, tickets, passes. Please check the SEPTA • Temple University Fare Guide or the website for complete fare information QuietRide Car: Available on all weekday trains (Monday - Friday 4:00 a.m. -

Getting to Lankaneu Hospital Lankenau Medical Center Is

Getting to Lankaneu Hospital Lankenau Medical Center is located just outside the western city limits of Philadelphia in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania (Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County). Philadelphia is served by national train and bus transportation, and by national and international air transportation. Once in Philadelphia, you can get to Lankenau Medical Center by car, taxi, train or bus. Lankenau Medical Center 100 East Lancaster Avenue, Wynnewood, PA 19096 484.476.2000 By car • From the North – Take I-95 South to Philadelphia. Exit I-95 onto I-676/76 West in Philadelphia. Exit I-76 onto City Avenue, and turn right at the bottom of the ramp. Travel several miles South on Route 1 (City Line Avenue) to the intersection of Route 30 (Lancaster Avenue). Turn right onto Lancaster Avenue to the first traffic light. The hospital will be on your left. • From the South – Take I-95 North. Exit I-95 onto I-476 North. Exit I-476 at the Route 1 Exit. Follow Route 1 North several miles to Route 30 (Lancaster Avenue). Turn left on Route 30 (West) to first traffic light. The hospital will be on your left. • From the East/West – Take the Pennsylvania Turnpike to the Valley Forge Interchange (Exit 326). Exit onto I-76 East. Follow to Route 1 Exit (City Line Avenue). Exit South onto Route 1, follow for several miles to Route 30 (Lancaster Avenue). Turn right (West) onto Route 30 to first traffic light. The hospital will be on your left. By bus or train From Center City Philadelphia and West to Paoli • By train – From Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, Suburban Station, or Market East Station, take SEPTA’s Regional Rail Paoli/Thorndale Line to either Overbrook or Wynnewood. -

Warminster Linepublictimetable Layout12/27/201512:16Pmpage

Warminster LinePublicTimetable_Layout12/27/201512:16PMPage SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS and MAJOR HOLIDAYS FareServices Train Number 401 499 403 405 407 411 415 419 423 427 431 435 439 443 447 451 455 459 463 467 471 475 Zone Ê*ËStations AM AM AM AM AM AM AM AMAM AM AM PMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPMPM 3 DDWarminster — — — — 5:41 6:41 7:41 8:41 9:41 10:41 11:41 12:41 1:41 2:41 3:41 4:41 5:41 6:41 7:41 8:41 9:41 — 3 D Hatboro — — — — 5:45 6:45 7:45 8:45 9:45 10:45 11:45 12:45 1:45 2:45 3:45 4:45 5:45 6:45 7:45 8:45 9:45 — 3 D Willow Grove — — — — 5:49 6:49 7:49 8:49 9:49 10:49 11:49 12:49 1:49 2:49 3:49 4:49 5:49 6:49 7:49 8:49 9:49 — 3 DDCrestmont — — — — F5:51 F6:51 F7:51 F8:51 F9:51 F10:51 F11:51 F12:51 F1:51 F2:51 F3:51 F4:51 F5:51 F6:51 F7:51 D8:51 D9:51 — 3 DDRoslyn — — — — 5:53 6:53 7:53 8:53 9:53 10:53 11:53 12:53 1:53 2:53 3:53 4:53 5:53 6:53 7:53 8:53 9:53 — 3 DDArdsley — — — — 5:56 6:56 7:56 8:56 9:56 10:56 11:56 12:56 1:56 2:56 3:56 4:56 5:56 6:56 7:56 8:56 9:56 — 3 D Glenside — 4:29 4:59 5:29 5:59 6:59 7:59 8:59 9:59 10:59 11:59 12:59 1:59 2:59 3:59 4:59 5:59 6:59 7:59 8:59 9:59 10:59 3 DD Jenkintown-Wyncote — 4:31 5:01 5:31 6:01 7:01 8:01 9:01 10:01 11:01 12:01 1:01 2:01 3:01 4:01 5:01 6:01 7:01 8:01 9:01 10:01 11:01 2 D Elkins Park — 4:33 5:03 5:33 6:03 7:03 8:03 9:03 10:03 11:03 12:03 1:03 2:03 3:03 4:03 5:03 6:03 7:03 8:03 9:03 10:03 11:03 2 DDMelrose Park — 4:35 5:05 5:35 6:05 7:05 8:05 9:05 10:05 11:05 12:05 1:05 2:05 3:05 4:05 5:05 6:05 7:05 8:05 9:05 10:05 11:05 1 DDFern Rock T.C. -

REGIONAL RAIL • West Trenton

STATION LOCATIONS CONNECTING SERVICES* SATURDAYS, SUNDAYS and MAJOR HOLIDAYS WEST TRENTON NJT Rt 608 )DUH 6HUYLFHV 7UDLQ1XPEHU 3 Railroad Ave =RQH Ê*Ë 6WDWLRQV $0 $0 $0 $0 30 30 30 30 30 YARDLEY REGIONAL RAIL WEST TRENTON 1- D :HVW7UHQWRQ1- 13 Reading Ave DD<DUGOH\ WOODBOURNE :RRGERXUQH D 903 Woodbourne Rd LINE D /DQJKRUQH LANGHORNE 215-580-6941 14 ,130 DD 1HVKDPLQ\)DOOV 137 Comly Ave To/From Center City Philadelphia DD 7UHYRVH NESHAMINY FALLS 58 DD 6RPHUWRQ 4255 E. Bristol Rd DD )RUHVW+LOOV TREVOSE Effective September 5, 2021 DD 3KLOPRQW 1100 Boundbrook Ave DD %HWKD\UHV SOMERTON 215-580-6940 58, 84 D 0HDGRZEURRN 13623 Philmont Ave • West Trenton D 5\GDO FOREST HILLS • Yardley 84 D 1REOH 299 Byberry Rd -HQNLQWRZQ:\QFRWH • Woodbourne DD PHILMONT 215-580-6939 72&(17(5&,7< D (ONLQV3DUN 106 Tomlinson Rd • Langhorne 0HOURVH3DUN DD BETHAYRES 215-580-6938 24, 88 • Neshaminy Falls DD)HUQ5RFN7& 500 Station Ave & D 7HPSOH8QLYHUVLW\ MEADOWBROOK • Trevose & DD-HIIHUVRQ6WDWLRQ 1430 Old Valley Rd • Somerton & DD6XEXUEDQ6WDWLRQ RYDAL & DDWK6WUHHW6WDWLRQ 1470 Susquehanna Rd • Forest Hills & D3HQQ0HGLFLQH6WDWLRQ NOBLE 55 7UDLQFRQWLQXHVWR $,5$,5 $,5$,5 $,5$,5 $,5$,5 $,5 801 Old York Rd • Philmont VHH'HVWLQDWLRQ&RGHV $0$0$0303030303030 JENKINTOWN-WYNCOTE • Bethayres 215-580-6838 77 2 Greenwood Ave • Meadowbrook )DUH 6HUYLFHV 7UDLQ1XPEHU ELKINS PARK 215-580-6887 28 =RQH Ê*Ë 6WDWLRQV $0 $0 $0 30 30 30 30 30 30 7876 Spring Ave • Rydal & D 3HQQ0HGLFLQH6WDWLRQ MELROSE PARK 215-580-6891 • Noble & DDWK6WUHHW6WDWLRQ 900 Valley Rd & DD6XEXUEDQ6WDWLRQ FERN ROCK TRANS. CENTER • Jenkintown-Wyncote 4, 28, 57, 70, BSL & DD-HIIHUVRQ6WDWLRQ 900 Nedro Ave • Elkins Park &D 7HPSOH8QLYHUVLW\ TEMPLE UNIVERSITY DD)HUQ5RFN7& 215-580-5440 • Melrose Park DD0HOURVH3DUN 927 W. -

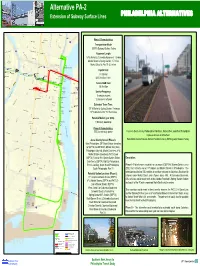

Alternative PA-2 Extension of Subway Surface Lines PHILADELPHIA ALTERNATIVES

Alternative PA-2 Extension of Subway Surface Lines PHILADELPHIA ALTERNATIVES T u 6 T 1 S 8 S t R e GI H R , ARD e T AV 7 r 4 t 2 R S , 6 Girard d ! R a North , T o 5 S r Phase I Characteristics: Philadelphia R H B , FA T IRMOUNT AV 3 5 95 Fairmount R ¨¦§ (! , T 2 S R T , H S T 1 P Transportation Mode: O 6 T R P 3 L S A 1 GR R 2 E S EN ST T SEPTA Subway-Surface Trolley T SPR EN S 76 ING G GARD ARDEN G ¨¦§ T SPRIN B ST E S N Spring Garden J H A T T M Alignment Length: I 5 S N 1 F B D R r R A o N 3 th K a 3 L CALL d 13 & Market to Columbus Boulevard: 1.2 miles IN OWHIL - Spring Garden!(! P ST R Y id g West e Market Street to Spring Garden: 1.7 miles S Philadelphia p u r CA T LLOWH S IL S Festival T Market Street to Pier 70: 2.2 miles D Race-Vine Pier N ! 676 2 ¨¦§ T Callowhill St/Festival Pier 34th & Market 2 !( S V T ! ! INE ST H 30 S th Chinatown Stree T t ! ! D St 8 a 1 (! tion R Capital Cost: !36th & Chestnut ! 3 33rd Street 22nd & Market Suburban Station RAC M ! ! E ST arket F PA rankfor !19th & Market TCO $1.0 billion d Line Market East Hi-S ! 36th & Sansom Piers 3 & 5 peed ! L T (! Be in n F e S 13th & Market AR !( ran CH S Piers kli $205.8 million / mile T n T (! !((! 3 & Br 11th & Market L 5 id S ! uxury ge 1 T A 2 p S 8th & Market art ! ments H !( 5th & Market K T ! A 6 Center Campbell R 1 2nd & Market T Annual O&M Cost: M City !(! Field A CHEST Walnut Locust NUT S Cooper Street $8.6 million University City ! ! T Riverlink ! 12th-13th & Locust Ferry Dock - Rutgers 15th-16th & Locust ! WAL ! 9th-10th & Locust NUT ST r T ! Independence