A Participatory Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis to Tackle a Complex Environmental Problem Involving Cultural Water Heritage and Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Finnish Environment Brought to You by CORE Provided by Helsingin Yliopiston445 Digitaalinen Arkisto the Finnish Eurowaternet

445 View metadata, citation and similar papersThe at core.ac.uk Finnish Environment The Finnish Environment brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston445 digitaalinen arkisto The Finnish Eurowaternet ENVIRONMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PROTECTION Jorma Niemi, Pertti Heinonen, Sari Mitikka, Heidi Vuoristo, The Finnish Eurowaternet Olli-Pekka Pietiläinen, Markku Puupponen and Esa Rönkä (Eds.) with information about Finnish water resources and monitoring strategies The Finnish Eurowaternet The European Environment Agency (EEA) has a political mandate from with information about Finnish water resources the EU Council of Ministers to deliver objective, reliable and comparable and monitoring strategies information on the environment at a European level. In 1998 EEA published Guidelines for the implementation of the EUROWATERNET monitoring network for inland waters. In every Member Country a monitoring network should be designed according to these Guidelines and put into operation. Together these national networks will form the EUROWATERNET monitoring network that will provide information on the quantity and quality of European inland waters. In the future they will be developed to meet the requirements of the EU Water Framework Directive. This publication presents the Finnish EUROWATERNET monitoring network put into operation from the first of January, 2000. It includes a total of 195 river sites, 253 lake sites and 74 hydrological baseline sites. Groundwater monitoring network will be developed later. In addition, information about Finnish water resources and current monitoring strategies is given. The publication is available in the internet: http://www.vyh.fi/eng/orginfo/publica/electro/fe445/fe445.htm ISBN 952-11-0827-4 ISSN 1238-7312 EDITA Ltd. PL 800, 00043 EDITA Tel. -

Koli National Park • Location: Joensuu, Kontiolahti, Lieksa • 30 Km2 • Established: 1991

Koli National Park • Location: Joensuu, Kontiolahti, Lieksa • 30 km2 • Established: 1991 Metsähallitus, Parks and Wildlife Finland • Ukko Visitor Centre, Ylä-Kolintie, Koli, tel. + 358 (0)206 39 5654 [email protected] • nationalparks.fi/koli • facebook.com/ kolinkansallispuisto National Park Please help us to protect nature: • Please respect nature and other hikers! Koli • Leave no traces of your visit behind. Safely combustible wastes can be burnt at campfire sites. into one of Finland’s national Metsähallitus manages Please take any other wastes away landscapes. The best loved cultural landscapes within the when you leave the park. vistas open up vellous view over national park, at the same time Light campfires is allowed in the Lake Pielinen from the top of preserving traditional farming • sites provided in the camping When you take in the mar- Ukko-Koli hill, it’s easy to see methods. Swidden fields are areas marked on the map. Lighting vellous view over Lake why this spot has attracted so cleared and burnt in the park’s campfires is forbidden if the forest many Finnish artists, photog- forests, meadows are mown by Pielinen from the top of fire warning is in effect. Ukko-Koli hill, it’s easy to see raphers and nature-lovers over hand, and cattle graze the park’s • You may freely walk, ski and row, in why this spot has attracted the centuries. The splendid pastures. scenery always instills a sense of the park, except in restricted areas. so many Finnish artists, serenity and wonder in visitors. Hilltops and meadows • Please keep pets on lead. -

SCHRIFTENREIHE DER DEUTSCHEN GESELLSCHAFT FÜR GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN GEOTOPE – DIALOG ZWISCHEN STADT UND LAND ISBN 978-3-932537-49-3 Heft 51 S

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundesanstalt in Wien Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 60 Autor(en)/Author(s): Nevaleinen Raimo, Nenonen Jari Artikel/Article: World Natural Heritage and Geopark Sites and Possible Candidates in Finland 135-139 ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at ABHANDLUNGEN DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Abh. Geol. B.-A. ISSN 0378-0864 ISBN 978-3-85316-036-7 Band 60 S. 135–139 Wien, 11.–16. Juni 2007 SCHRIFTENREIHE DER DEUTSCHEN GESELLSCHAFT FÜR GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN GEOTOPE – DIALOG ZWISCHEN STADT UND LAND ISBN 978-3-932537-49-3 Heft 51 S. 135–139 Wien, 11.–16. Juni 2007 11. Internationale Jahrestagung der Fachsektion GeoTop der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften Word Natural Heritage and Geopark Sites and Possible Candidates in Finland RAIMO NEVALAINEN & JARI NENONEN*) 8 Text-Figures Finnland Pleistozän Inlandeis UNESCO-Weltnaturerbe Österreichische Karte 1 : 50.000 Geopark Blätter 40, 41, 58, 59 Geotourismus Contents 1. Zusammenfassung . 135 1. Abstractt . 135 1. Saimaa-Pielinen Lakeland District . 136 2. Rokua – a Geological Puzzle . 136 3. Pyhä-Luosto National Park . 137 4. Kvarken . 138 2. References . 139 Weltnaturerbe und Geoparks und mögliche Kandidaten in Finnland Zusammenfassung Zurzeit gilt Tourismus als weltweit am schnellsten wachsender Wirtschaftszweig. In Finnland sind Geologie und geologische Sehenswürdigkeiten als Touristenziele sowie als Informationsquellen relativ neu und daher selten. Das Geologische Forschungszentrum von Finnland (GTK) arbeitet bereits seit etlichen Jahren daran, der Bevölkerung, der Tourismusbranche und Bildungsanstalten Wissen über das geologische Erbe zur Verfügung zu stellen. Eine wichtige Aufgabe ist ebenfalls gewesen, das geologische Wissen in der Grundschulausbildung zu erhöhen. -

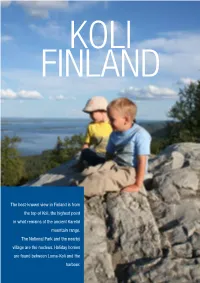

The Best-Known View in Finland Is from the Top of Koli, the Highest Point in What Remains of the Ancient Karelid Mountain Range

KOLI FINLAND The best-known view in Finland is from the top of Koli, the highest point in what remains of the ancient Karelid mountain range. The National Park and the nearby village are the nucleus. Holiday homes are found between Loma-Koli and the harbour. 1 UNIQBETWEENU EASET A NKOLID WEST Koli has been a meeting point between east- ern and western cultures for hundreds of years. It has a broad range of attractions: the geology of the area; the interplay between rock and water in the landscape; rich flora and fauna; and a living culture with remind- ers of a mystic past ever present. For over a century Koli has provided visitors with op- portunities for renewal and growth. As a centre for culture and nature Koli is A particular feature of the Koli landscape in unique. At its heart lies the National Park, winter is the snow-covered trees. In addi- where swidden culture (also known as slash- tion to glorious scenery Koli offers the steep- and-burn) is still regularly practised. Here est ski slopes in southern Finland; snowshoe you can also find the native ‘kyyttö’ cattle treks; fishing through the lake ice; driving the grazing as in days gone by. ice road; snowmobile and dog-team trails; extreme events; ski trails over hill and lake. Just You can reach the Park by water summer and some of the things that make Koli unique. E KOLI winter. In summer Finland’s only inland wa- U terway car-ferry plies between Koli and Liek- Regardless of the season, sunrise and sunset sa, in winter there is a road across the lake ice! at Koli – a dream come true. -

Water Quality of Lakes, Rivers and Sea Areas in Finland in 2000–2003

Water quality of lakes, rivers and sea areas in Finland in 2000–2003 Finland is known as a land of numerous lakes and The Baltic Sea is shallow with a mean depth of only Since the beginning of the 1970s, three national water clean waters. There are about 56 000 lakes with a 55 metres. The fact that the Baltic Sea forms a mostly protection programmes have been prepared, and the surface area of over one hectare and about 2600 lakes closed, shallow and cold brackish basin means that Government has adopted the two most recent ones. larger than one square kilometre. coastal waters are also highly vulnerable to pollution. In these programmes quantitative targets for the Harmful substances degrade slowly under the cold most important pollution sources were defi ned. The Because of the relatively cold climate and prevalent conditions and the winter ice cover prevents oxygen third national water protection programme approved pre-Cambrian bedrock, the rate of weathering is being transferred from the air to the surface water. by the Government in 1998 sets targets for the year slow and, therefore, the concentrations of inorganic 2005. The long-term goal is that the state of the Baltic substances in Finnish surface waters are low. By Finland has achieved good results in water protection Sea and of inland surface waters is not degraded any contrast, the concentrations of dissolved organic by setting quantitative national water protection further by human activities. The main aim of this substances, for example, humic acids, can be high targets with specifi c time frames. -

A Fishing Tour of Finland Blue Finland

© Visit Finland A Fishing Tour of Blue Finland – Experience a Land of Water, the Baltic Sea, Finnish Lakeland and Wild White Waters (12 Days) Day 1: Helsinki, the Capital of Finland Day 2: Vallisaari – Fortifications Overlooking The Finnish capital Helsinki is a modern city with the Baltic Sea over half a million residents. Helsinki offers lots Just 20 minutes by boat from the Market Square (where to see, do and experience for visitors of all ages – you can buy tasty local fresh fish and fish dishes), and also for keen fishers. the islands of Vallisaari and Kuninkaansaari , near the famous island fortress of Suomenlinna, are enchanting destinations for outings. The islands have a wider range of flora and fauna than anywhere else in the metropolitan area! A regular waterbus service from the Market Square to Vallisaari runs between May and September. After your day trip to Vallisaari drive east from Helsinki to the town of Kouvola. On your way, you might stop at Finland’s oldest arboretum at Mustila to admire its famous rhododendrons and a total of 250 tree species. Fishing enthusiasts should check out the mighty River Kymi, which © Visit Finland flows nearby . Accommodation: Hotels, campsites and hostels in The River Vantaa : Though the suburbs of Kouvola www.visitkouvola.fi Helsinki are nearby, the River Vantaa flows through beautiful natural scenery and farmland. There are many great places to fish from its banks, and you can get to the river easily from the city centre, also on local buses. • Vanhankaupunginkoski Rapids • Vantaankoski Rapids • Pitkäkoski Rapids www.iesite.fi/vantaanjoki Fishing guide: www.helsinkifishingguide.com Accommodation: Hotels, campsites and hostels in Helsinki www.visithelsinki.fi © Tuomo Hayrinen © Tuomo Activities: Helsinki Vallisaari island: The Alexander offers everyone accessible adventures in Tour (3 km) and the Kuninkaansaari Island Tour truly wild settings. -

Artic Food from Finland English Brochure for Marketers

Petri Jauhiainen/Luke Arctic food from Finland You know what you´re eating when you choose Arctic food Arctic Food from Finland 1 Erkki Oksanen/Luke FINNISH FOOD PRODUCTION IS UNIQUE When Finnish food is exported or served and communicated to foreign guests, it is backed by a unified story that builds the image of Finland as a responsible producer of pure food, an interesting country for food. The story strengthens the messages of individual companies and supports them in their internationalization. The purpose of this brochure is to help you communicate the special features of Finnish, Arctic food. The Arctic food concept, the unique characteristics of Finnish food, provides a consistent way for ex- porters to share the specific quality of Finnish food. It supports Finnish food exporters and promoters in their marketing activities, especially in commu- nication and brand building. Its key elements are Finland’s Arctic, natural growing environment, and our expertise ensuring clean, high-quality and tasty food. Let us introduce the uniqueness of Finnish Arctic food. o 60 Arctic food production means Finland, 60 degrees north, the northern latitude region for food production. Finland is the northernmost place on earth where food is produced on this scale. 2 Arctic Food from Finland CC0/Arctic Food From Finland/Ruokatieto Rapeseed and field mustard, oil plants cultivated in Finland. Finnish food production is one of the world’s most sustainable. Good practices in primary production are the basis for high quality food. Environmental Arctic food issues and animal welfare are key focus areas. It’s unique. Finnish food is pure, and throughout the food chain its hygiene, traceability and accountability are Our dark arctic winters and long among the best in the world. -

Varve Distribution Reveals Spatiotemporal Hypolimnetic Hypoxia Oscillations During the Past 200 Years in Lake Lehmilampi, Eastern Finland

quaternary Article Varve Distribution Reveals Spatiotemporal Hypolimnetic Hypoxia Oscillations During the Past 200 Years in Lake Lehmilampi, Eastern Finland Sarianna Salminen 1,*, Saija Saarni 1 , Mira Tammelin 1, Yu Fukumoto 2 and Timo Saarinen 1 1 Department of Geography and Geology, University of Turku, FIN-20014 Turku, Finland; saitur@utu.fi (S.S.); mira.tammelin@utu.fi (M.T.); tijusa@utu.fi (T.S.) 2 Research center for Pan-Pacific civilizations, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto 603–8577, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: sarsalm@utu.fi; Tel.: +358-408-484-783 Received: 15 January 2019; Accepted: 22 May 2019; Published: 26 May 2019 Abstract: We investigated 34 sediment cores to reconstruct spatiotemporal variations in hypolimnetic hypoxia for the past 200 years in Lehmilampi, a small lake in Eastern Finland. As hypoxia is essential for varve preservation, spatiotemporal changes in varve distribution were used as an indicator for hypolimnetic hypoxia oscillations. The hypoxic water volume was used as a variable reflecting hypolimnetic hypoxia and determined for each year by estimating the water volume beneath the water depth where shallowest varves were preserved. As a result, seven hypoxia periods, highlighting the variations in hypolimnetic hypoxia, are established. These periods may be influenced by bioturbation, lake infill, and lake level changes. Furthermore, we evaluated the relationship between hypolimnetic hypoxia oscillations and climatic factors. Diatom assemblage changes were also analyzed to estimate whether the hypoxia periods could be related to anthropogenic eutrophication. The diatom analyses suggest relatively stable nutrient conditions for the past 200 years in Lake Lehmilampi. Climate, on the other hand, seems to be an important driver of hypoxia oscillations based on correlation analysis. -

Alternative Stable States in Large Shallow Lakes?

Journal of Great Lakes Research 40 (2014) 813–826 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Great Lakes Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jglr Review Alternative stable states in large shallow lakes? Annette B.G. Janssen a,b,⁎, Sven Teurlincx a, Shuqing An c, Jan H. Janse a,d,HansW.Paerle,WolfM.Mooija,b a Department of Aquatic Ecology, Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), P.O. Box 50, 6700 AB Wageningen, The Netherlands b Department of Aquatic Ecology and Water Quality Management, Wageningen University, The Netherlands c School of Life Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, PR China d PBL, Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, P.O. Box 303, 3720 AH Bilthoven, The Netherlands e Institute of Marine Sciences, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 3431 Arendell Street, Morehead City, NC 28557, USA article info abstract Article history: Many lakes worldwide are experiencing great change due to eutrophication. Consequently, species composition Received 16 April 2014 changes, toxic algal blooms proliferate, and drinking water supplies dwindle. The transition to the deteriorated Accepted 10 September 2014 state can be catastrophic with an abrupt change from macrophyte to phytoplankton domination. This has been Available online 16 October 2014 shown repeatedly in small lakes. Whether such alternative stable states also exist in large shallow lakes is less clear, however. Here we discuss the characteristics that give rise to alternative stable states in large shallow Communicated by Robert McKay lakes either in the lake as whole or restricted to specific regions of the lake. We include the effect of lake size, spa- Index words: tial heterogeneity and internal connectivity on a lake's response along the eutrophication axis. -

Effects of Temporal Variation in the Risk of Predation by Least Weasel

Evolutionary Ecology 17: 477–489, 2003. Ó 2003 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Research article Effects of temporal variation in the risk of predation by least weasel (Mustela nivalis) on feeding behavior of field vole (Microtus agrestis) ELINA KOIVISTO and JYRKI PUSENIUS* Department of Biology, Joensuu University, PO Box 111, FIN-80101 Joensuu, Finland (*author for correspondence, tel.: +358-13-2513582, e-mail: jyrki.pusenius@joensuu.fi) Received 8 November 2002; accepted 29 July 2003 Co-ordinating editor: V. Kaitala Abstract. Predation risk tends to vary in time. Thus prey animals face a problem of allocating feeding and antipredator effort across different risk situations. A recent model of Lima and Bed- nekoff (1999) predicts that a prey should allocate more feeding effort to low risk situations and more antipredator effort to high risk situations with increasing relative degree of risk in high risk situations (attack ratio). Furthermore when the proportion of time the prey spends in the high risk situation (p) increases, the prey have to eventually feed also in the high risk situations. However the increase in feeding effort in low risk situations should clearly exceed that in high risk situations as p increases. To test these predictions we measured feeding effort of field voles (Microtus agrestis) exposed to varying presence of least weasel (Mustela nivalis) and its feces in laboratory conditions. We generated quantitative predictions by estimating attack ratios from results of a pilot experi- ment. The model explained 15% of the observed variation in feeding effort of voles. Further analyses indicated that feeding effort was lower in high risk situations than in low risk situations at high attack ratio, but not at a lower one. -

Pielisen Kierros Nähtävyyksiä Pielisen Kierros -Pyöräilyreitti Kiertää Nimensä Mukaisesti Erä- Maisen, Suomen Neljäksi Suurimman Järven, Pielisen

Pielisen Kierros Nähtävyyksiä Pielisen Kierros -pyöräilyreitti kiertää nimensä mukaisesti erä- maisen, Suomen neljäksi suurimman järven, Pielisen. Pyöräillen pääset tutustumaan Suomen tunnetuimpaan kansallismaise- Points of interest maan, Koliin ja Kolin kansallispuistoon monesta näkökulmasta. Reitin varrella on myös muita nähtävyyksiä. Reitti kulkee pää- 1 Kolin näköalapaikat – näkymät kansallismaisemaan, osin rauhallisilla hiekkateillä maaseudulla. Kaikkiaan matkaa on Kolin luontokeskus Ukko – pysyvä ja vaihtuvat näyttelyt noin 250 kilometriä. Kierroksen etappeina on majoitusyrityksiä, Koli observation points – Views over the national ja näiden välisiä matkoja suositellaan päivän mittaiseksi retkek- park, Koli Nature Centre Ukko – Permanent and tempo- si. Koko reitin kiertämiseen kannattaakin varata useampi päivä. rary exhibitions Reitistä voi myös helposti valita sopivia osuuksia tai tehdä joko eteläisen tai pohjoisen reitin matkustamalla noin puolessa välissä Pielisen yli laivalla. Matkalle mukaan kannattaa ottaa 2 Pirunkirkko – Z-kirjaimen mallinen 34 metriä pitkä vähintään kartta ja reittiselosteet. Selosteet ovat tulostettavissa ja 1–7 metriä korkea rakoluola sivulla: ww.koli.fi/pyoraily. Pirunkirkko (“Devil’s Church”) – 34-metre crevice in the shape of a Z with a depth of 1–7 metres Pielinen Tour The Pielinen Tour cycling route circles the fourth largest lake 3 Ahveninen ja Punainen Talo – upeat maisemat Pieliselle in Finland, Pielinen. Cycling is a great way to discover the most ja historiallinen talo palveluineen famous national landscape in Finland in Koli and Koli National Ahveninen and Punainen Talo – Splendid views over Lake Park from multiple perspectives. There are lots of other points of Pielinen and a historic red house with services interest along the way too. Most of the cycling route is on quiet dirt roads in the countryside. -

The Finnish Landscape and Its Meanings

The Finnish landscape and its meanings PETRI J. RAIVO Petri J. Raivo (2002). The Finnish landscape and its meanings. Fennia 180: 1–2, pp. 89–98. Helsinki. ISSN 0015-0010. The landscape has played – and continues to play – an important role in the process of constructing a national identity in Finland. In this process, certain areas and views, whether real or imaginary, are designated as vital symbols of the national culture. The landscape is not merely an image, a map or a view of the existing motherland, however. It is also a part of the nation’s history, which is marked in the landscape in the form of significant buildings and mon- uments to historical events, so that the past may be seen as forming an unbro- ken continuum with the present. Work is constantly going on to maintain and renew the national traditions of landscape description. This means that what- ever its age and nostalgic associations, the landscape is an integral part of our present-day lives. The images, maps, and discourses associated with the land- scape may have altered in the course of time, and even the physical areas or views may have been replaced with new ones, but the ideal of a Finnish land- scape has persisted. The signs and significations attached to it thus remain a powerful part of our national culture. Petri J. Raivo, Academy of Finland (project 4872), Department of Geography, FIN-90014 University of Oulu, Finland. E-mail: [email protected] Three faces of the same scene all three. A landscape can thus have many faces, or, in other words, one landscape has numerous Landscape is one of those words whose meaning new landscapes opening up within it.