Geography from the Margins Tero Mustonen (Ed.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Post-Caledonian Dolerite Dyke from Magerøy, North Norway: Age and Geochemistry

A post-Caledonian dolerite dyke from Magerøy, North Norway: age and geochemistry DAVID ROBERTS, JOHN G. MITCHELL & TORGEIR B. ANDERSEN Roberts. D., Mitchell, J. G. & Andersen, T. B.: A post-Caledonian dolerite dyke from Magerøy, North Norway: age and geochemistry. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 71, pp. 28�294. Oslo 1991 . ISSN 0029-196X. A post-Caledonian, NW-SE trending, dolerite dyke on Magerøy has a geochemicalsignature comparable to that of continental tholeiites. Clinopyroxenes from three samples of the dolerite gave K-Ar ages of ca. 312, ca. 302 and ca. 266 Ma, suggesting a Perrno-Carboniferous age. In view of low K20 contents of the pyroxenes and the possible presence of excess argon, it is argued that the most reliable estimate of the emplacement age of the dyke is provided by the unweighted mean value, namely 293 ± 22 Ma. This Late Carboniferous age coincides with the later stages of a major phase of rifting and crustal extension in adjacent offshore areas. The dyke is emplaced along a NW-SE trending fault. Parallel or subparallel faults on Magerøy and in other parts of northem Finnmark may thus carry a component of Carboniferous crustal extension in their polyphase movement histories. David Roberts, Geological Survey of Norway, Post Box 3006-Lade, N-7(}()2 Trondheim, Norway; John G. Mitchell, Department of Physics, The University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, England; Torgeir B. Andersen, Institutt for geologi, Post Box 1047, University of Oslo, N-41316 Oslo 3, Norway. In the Caledonides of northernmost Norway, maficdy kes tolites indicate an Early Silurian (Llandovery) age (Hen are common in many parts of the metamorphic allochthon ningsmoen 1961; Føyn 1967; Bassett 1985) for part of the and are invariably deformed and metamorphosed, locally succession. -

Hele Troms Og Finnmark Hele Tromsø

Fylkestingskandidater Kommunestyrekandidater 1 2 3 1 2 3 Ivar B. Prestbakmo Anne Toril E. Balto Irene Lange Nordahl Marlene Bråthen Mats Hegg Jacobsen Olaug Hanssen Salangen Karasjok Sørreisa 4 5 6 4 5 6 Fred Johnsen Rikke Håkstad Kurt Wikan Edmund Leiksett Rita H. Roaldsen Magnus Eliassen Tana Bardu Sør-Varanger 7. Kine Svendsen 16. Hans-Ole Nordahl 25. Tore Melby Hele Hele 8. Glenn Maan 17. May Britt Pedersen 26. Kjell Borch 7. Marlene Bråthen, 10. Hugo Salamonsen, 13. Kurt Michalsen, 9. Wenche Skallerud 18. Frode Pettersen 27. Ole Marius Johnsen Tromsø Nordkapp Skjervøy 10. Bernt Bråthen 19. Mona Wilhelmsen 28. Sigurd Larsen 8. Jan Martin Rishaug, 11. Linn-Charlotte 14. Grethe Liv Olaussen, Troms og Finnmark Tromsø 11. Klaus Hansen 20. Fredrik Hanssen 29. Per-Kyrre Larsen Alta Nordahl, Sørreisa Porsanger 12. Ida Johnsen 21. Dag Nordvang 30. Peter Ørebech 9. Karin Eriksen, 12. Klemet Klemetsen, 15. Gunnleif Alfredsen, 13. Kathrine Strandli 22. Morten Furunes 31. Sandra Borch Kvæfjord Kautokeino Senja senterpartiet.no/troms senterpartiet.no/tromso 14. John Ottosen 23. Asgeir Slåttnes 15. Judith Maan 24. Kåre Skallerud VÅR POLITIKK VÅR POLITIKK Fullstendig program finner du på Fullstendig program finner du på For hele Tromsø senterpartiet.no/tromso for hele Troms og Finnmark senterpartiet.no/troms anlegg og andre stukturer tilpas- Senterpartiet vil ha tjenester Det skal være trygt å bli Næringsutvikling – det er i • Øke antallet lærlingeplasser. nord, for å styrke vår identitet og set aktivitet og friluftsliv Mulighetenes landsdel Helse og beredskap nær folk og ta hele Tromsø i gammel i Tromsø nord verdiene skapes Senterpartiet vil: Senterpartiet vil: • Utvide borteboerstipendet, øke stolthet. -

The Finnish Environment Brought to You by CORE Provided by Helsingin Yliopiston445 Digitaalinen Arkisto the Finnish Eurowaternet

445 View metadata, citation and similar papersThe at core.ac.uk Finnish Environment The Finnish Environment brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston445 digitaalinen arkisto The Finnish Eurowaternet ENVIRONMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION PROTECTION Jorma Niemi, Pertti Heinonen, Sari Mitikka, Heidi Vuoristo, The Finnish Eurowaternet Olli-Pekka Pietiläinen, Markku Puupponen and Esa Rönkä (Eds.) with information about Finnish water resources and monitoring strategies The Finnish Eurowaternet The European Environment Agency (EEA) has a political mandate from with information about Finnish water resources the EU Council of Ministers to deliver objective, reliable and comparable and monitoring strategies information on the environment at a European level. In 1998 EEA published Guidelines for the implementation of the EUROWATERNET monitoring network for inland waters. In every Member Country a monitoring network should be designed according to these Guidelines and put into operation. Together these national networks will form the EUROWATERNET monitoring network that will provide information on the quantity and quality of European inland waters. In the future they will be developed to meet the requirements of the EU Water Framework Directive. This publication presents the Finnish EUROWATERNET monitoring network put into operation from the first of January, 2000. It includes a total of 195 river sites, 253 lake sites and 74 hydrological baseline sites. Groundwater monitoring network will be developed later. In addition, information about Finnish water resources and current monitoring strategies is given. The publication is available in the internet: http://www.vyh.fi/eng/orginfo/publica/electro/fe445/fe445.htm ISBN 952-11-0827-4 ISSN 1238-7312 EDITA Ltd. PL 800, 00043 EDITA Tel. -

Koli National Park • Location: Joensuu, Kontiolahti, Lieksa • 30 Km2 • Established: 1991

Koli National Park • Location: Joensuu, Kontiolahti, Lieksa • 30 km2 • Established: 1991 Metsähallitus, Parks and Wildlife Finland • Ukko Visitor Centre, Ylä-Kolintie, Koli, tel. + 358 (0)206 39 5654 [email protected] • nationalparks.fi/koli • facebook.com/ kolinkansallispuisto National Park Please help us to protect nature: • Please respect nature and other hikers! Koli • Leave no traces of your visit behind. Safely combustible wastes can be burnt at campfire sites. into one of Finland’s national Metsähallitus manages Please take any other wastes away landscapes. The best loved cultural landscapes within the when you leave the park. vistas open up vellous view over national park, at the same time Light campfires is allowed in the Lake Pielinen from the top of preserving traditional farming • sites provided in the camping When you take in the mar- Ukko-Koli hill, it’s easy to see methods. Swidden fields are areas marked on the map. Lighting vellous view over Lake why this spot has attracted so cleared and burnt in the park’s campfires is forbidden if the forest many Finnish artists, photog- forests, meadows are mown by Pielinen from the top of fire warning is in effect. Ukko-Koli hill, it’s easy to see raphers and nature-lovers over hand, and cattle graze the park’s • You may freely walk, ski and row, in why this spot has attracted the centuries. The splendid pastures. scenery always instills a sense of the park, except in restricted areas. so many Finnish artists, serenity and wonder in visitors. Hilltops and meadows • Please keep pets on lead. -

SCHRIFTENREIHE DER DEUTSCHEN GESELLSCHAFT FÜR GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN GEOTOPE – DIALOG ZWISCHEN STADT UND LAND ISBN 978-3-932537-49-3 Heft 51 S

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundesanstalt in Wien Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 60 Autor(en)/Author(s): Nevaleinen Raimo, Nenonen Jari Artikel/Article: World Natural Heritage and Geopark Sites and Possible Candidates in Finland 135-139 ©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at ABHANDLUNGEN DER GEOLOGISCHEN BUNDESANSTALT Abh. Geol. B.-A. ISSN 0378-0864 ISBN 978-3-85316-036-7 Band 60 S. 135–139 Wien, 11.–16. Juni 2007 SCHRIFTENREIHE DER DEUTSCHEN GESELLSCHAFT FÜR GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN GEOTOPE – DIALOG ZWISCHEN STADT UND LAND ISBN 978-3-932537-49-3 Heft 51 S. 135–139 Wien, 11.–16. Juni 2007 11. Internationale Jahrestagung der Fachsektion GeoTop der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften Word Natural Heritage and Geopark Sites and Possible Candidates in Finland RAIMO NEVALAINEN & JARI NENONEN*) 8 Text-Figures Finnland Pleistozän Inlandeis UNESCO-Weltnaturerbe Österreichische Karte 1 : 50.000 Geopark Blätter 40, 41, 58, 59 Geotourismus Contents 1. Zusammenfassung . 135 1. Abstractt . 135 1. Saimaa-Pielinen Lakeland District . 136 2. Rokua – a Geological Puzzle . 136 3. Pyhä-Luosto National Park . 137 4. Kvarken . 138 2. References . 139 Weltnaturerbe und Geoparks und mögliche Kandidaten in Finnland Zusammenfassung Zurzeit gilt Tourismus als weltweit am schnellsten wachsender Wirtschaftszweig. In Finnland sind Geologie und geologische Sehenswürdigkeiten als Touristenziele sowie als Informationsquellen relativ neu und daher selten. Das Geologische Forschungszentrum von Finnland (GTK) arbeitet bereits seit etlichen Jahren daran, der Bevölkerung, der Tourismusbranche und Bildungsanstalten Wissen über das geologische Erbe zur Verfügung zu stellen. Eine wichtige Aufgabe ist ebenfalls gewesen, das geologische Wissen in der Grundschulausbildung zu erhöhen. -

Russian Fishing Activities Off the Coast of Finnmark*A Legal History1 Kirsti Strøm Bull*, Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Arctic Review on Law and Politics Vol. 6, No. 1, 2015, pp. 3Á10 Russian Fishing Activities off the Coast of Finnmark*A Legal History1 Kirsti Strøm Bull*, Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway Abstract The rich fishery resources off the coast of Finnmark have historically attracted fishermen from other parts of Norway and from neighbouring countries. This article discusses the legal history of Russian fishing activities off the coast of Finnmark and covers the historical period from the 1700s until the termination of this fishery in the early 1900s. The article shows that Russian fishermen, like the Sa´mi from Finland*and unlike fishermen from other nations, were authorized to establish shacks and landing places. Both the agreements and legal disputes surrounding the fishery, which lasted until World War I, are discussed in the article. Keywords: fishery; Russia; legal history; rights to marine resources; Finnmark; The Lapp Codicil Received: August 2014; Accepted: September 2014; Published: March 2015 1. Introduction protecting fishery resources for the benefit of Finnmark’s own population* From far back in time, the rich fisheries off the coast of Finnmark have attracted fishermen from beyond the county’s own borders. Some of these fishermen, known in Norwegian as nordfarere (‘‘northern seafarers’’), came from further south along the Norwegian coast, specifically from the counties of Nordland and Trøndelag. Others came from further east, from Finland and Russia. In more recent times, fishermen started to arrive from even further afield, notably from England. When the English trawlers ventured into Varangerfjord in 1911, they triggered a dispute between Norway and England concerning the delimitation of the Norwegian fisheries zone that continued until 1951, when the matter was decided by the International Court of Justice in The Hague. -

The Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP)

The Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) Your ref Our ref Date 18/2098-13 27 February 2019 The Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP) – Norway's contribution to the report focusing on recognition, reparation and reconciliation With reference to the letter of 20th November 2018 from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights where we were invited to contribute to the report of the Expert Mechanism on recognition, reparation and reconciliation initiatives in the last 10 years. Development of the Norwegian Sami policy For centuries, the goal of Norwegian Sami policy was to assimilate the Sami into the Norwegian population. For instance Sami language was banned in schools. In 1997 the King, on behalf of the Norwegian Government, gave an official apology to the Sami people for the unjust treatment and assimilation policies. The Sami policy in Norway today is based on the recognition that the state of Norway was established on the territory of two peoples – the Norwegians and the Sami – and that both these peoples have the same right to develop their culture and language. Legislation and programmes have been established to strengthen Sami languages, culture, industries and society. As examples we will highlight the establishment of the Sámediggi (the Sami parliament in Norway) in 1989, the Procedures for Consultations between the State Authorities and Sámediggi of 11 May 2005 and the Sami Act. More information about these policies can be found in Norway's reports on the implementation of the ILO Convention No. 169 and relevant UN Conventions. -

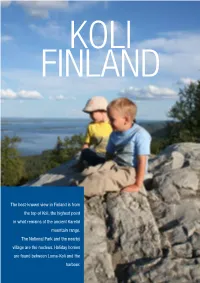

The Best-Known View in Finland Is from the Top of Koli, the Highest Point in What Remains of the Ancient Karelid Mountain Range

KOLI FINLAND The best-known view in Finland is from the top of Koli, the highest point in what remains of the ancient Karelid mountain range. The National Park and the nearby village are the nucleus. Holiday homes are found between Loma-Koli and the harbour. 1 UNIQBETWEENU EASET A NKOLID WEST Koli has been a meeting point between east- ern and western cultures for hundreds of years. It has a broad range of attractions: the geology of the area; the interplay between rock and water in the landscape; rich flora and fauna; and a living culture with remind- ers of a mystic past ever present. For over a century Koli has provided visitors with op- portunities for renewal and growth. As a centre for culture and nature Koli is A particular feature of the Koli landscape in unique. At its heart lies the National Park, winter is the snow-covered trees. In addi- where swidden culture (also known as slash- tion to glorious scenery Koli offers the steep- and-burn) is still regularly practised. Here est ski slopes in southern Finland; snowshoe you can also find the native ‘kyyttö’ cattle treks; fishing through the lake ice; driving the grazing as in days gone by. ice road; snowmobile and dog-team trails; extreme events; ski trails over hill and lake. Just You can reach the Park by water summer and some of the things that make Koli unique. E KOLI winter. In summer Finland’s only inland wa- U terway car-ferry plies between Koli and Liek- Regardless of the season, sunrise and sunset sa, in winter there is a road across the lake ice! at Koli – a dream come true. -

Water Quality of Lakes, Rivers and Sea Areas in Finland in 2000–2003

Water quality of lakes, rivers and sea areas in Finland in 2000–2003 Finland is known as a land of numerous lakes and The Baltic Sea is shallow with a mean depth of only Since the beginning of the 1970s, three national water clean waters. There are about 56 000 lakes with a 55 metres. The fact that the Baltic Sea forms a mostly protection programmes have been prepared, and the surface area of over one hectare and about 2600 lakes closed, shallow and cold brackish basin means that Government has adopted the two most recent ones. larger than one square kilometre. coastal waters are also highly vulnerable to pollution. In these programmes quantitative targets for the Harmful substances degrade slowly under the cold most important pollution sources were defi ned. The Because of the relatively cold climate and prevalent conditions and the winter ice cover prevents oxygen third national water protection programme approved pre-Cambrian bedrock, the rate of weathering is being transferred from the air to the surface water. by the Government in 1998 sets targets for the year slow and, therefore, the concentrations of inorganic 2005. The long-term goal is that the state of the Baltic substances in Finnish surface waters are low. By Finland has achieved good results in water protection Sea and of inland surface waters is not degraded any contrast, the concentrations of dissolved organic by setting quantitative national water protection further by human activities. The main aim of this substances, for example, humic acids, can be high targets with specifi c time frames. -

A Fishing Tour of Finland Blue Finland

© Visit Finland A Fishing Tour of Blue Finland – Experience a Land of Water, the Baltic Sea, Finnish Lakeland and Wild White Waters (12 Days) Day 1: Helsinki, the Capital of Finland Day 2: Vallisaari – Fortifications Overlooking The Finnish capital Helsinki is a modern city with the Baltic Sea over half a million residents. Helsinki offers lots Just 20 minutes by boat from the Market Square (where to see, do and experience for visitors of all ages – you can buy tasty local fresh fish and fish dishes), and also for keen fishers. the islands of Vallisaari and Kuninkaansaari , near the famous island fortress of Suomenlinna, are enchanting destinations for outings. The islands have a wider range of flora and fauna than anywhere else in the metropolitan area! A regular waterbus service from the Market Square to Vallisaari runs between May and September. After your day trip to Vallisaari drive east from Helsinki to the town of Kouvola. On your way, you might stop at Finland’s oldest arboretum at Mustila to admire its famous rhododendrons and a total of 250 tree species. Fishing enthusiasts should check out the mighty River Kymi, which © Visit Finland flows nearby . Accommodation: Hotels, campsites and hostels in The River Vantaa : Though the suburbs of Kouvola www.visitkouvola.fi Helsinki are nearby, the River Vantaa flows through beautiful natural scenery and farmland. There are many great places to fish from its banks, and you can get to the river easily from the city centre, also on local buses. • Vanhankaupunginkoski Rapids • Vantaankoski Rapids • Pitkäkoski Rapids www.iesite.fi/vantaanjoki Fishing guide: www.helsinkifishingguide.com Accommodation: Hotels, campsites and hostels in Helsinki www.visithelsinki.fi © Tuomo Hayrinen © Tuomo Activities: Helsinki Vallisaari island: The Alexander offers everyone accessible adventures in Tour (3 km) and the Kuninkaansaari Island Tour truly wild settings. -

Caledonian Nappe Sequence of Finnmark, Northern Norway, and the Timing of Orogenic Deformation and Metamorphism

Caledonian Nappe Sequence of Finnmark, Northern Norway, and the Timing of Orogenic Deformation and Metamorphism B. A. STURT Geologisk Institutt, adv. A, Joachim Frielesgt. 1, Bergen, Norway I. R. PRINGLE Department of Geophysics, Madingley Road, Cambridge, England D. ROBERTS Norges Geologiske Undersakelse, Postboks 3006, Trondheim, Norway ABSTRACT and have a varying metamorphic state, reaching at least into garnet grade (Holtedahl and others, 1960). The exact relation between On the basis of regional, structural, and metamorphic studies these rocks on Mageray and the older Caledonian metamorphic combined with age determinations, it is demonstrated that the in- complex of the Kalak Nappe are, however, not yet established. ternal metamorphic fabrics of the main nappe sequence of Finn- Correlations made by a number of authors equate, with the mark, northern Norway, developed during an Early Ordovician obvious exception of the younger sedimentary rocks of Magertfy, phase of the Caledonian orogeny (Grampian?); the cleavage de- the rocks of the Finnmark nappe pile with the upper Pre- velopment in the autochthon also belongs to this phase. The final cambrian-Tremadoc sequence of the foreland autochthon. This mise-en-place of the thrust-nappe sequence, however, appears to correlation indicates that- the entire Caledonian sequence of the belong to a later phase of Caledonian orogenic development, prob- nappe pile (without Mageroy) and immediately underlying au- ably toward the end of the Silurian Period, as does the deformation tochthon is upper Precambrian, passing conformably up at least and metamorphism of the Silurian sequence of Mageray. The into the lower part of the Tremadoc. The nappe units beneath the geochronological results also give information regarding the posi- Kalak Nappe, although of lower metamorphic grade, have a simi- tioning of the lower boundaries to the Cambrian and Ordovician lar structural sequence. -

Our. Knowledge of the Geology of the Alta District of West Finnmark Owes Much to the Work of Holtedahl (1918, 1960) and Føyn (1964)

Correlation of Autochthonous Stratigraphical Sequences in the Alta-Repparfjord Region, West Finnmark DAVID ROBERTS & EIGILL FARETH Roberts, D. & Fareth, E.: Correlation of autochthonous stratigraphical se quences in the Alta-Repparfjord region, west Finnmark. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 54, pp. 123-129. Oslo 1974. An outline of the geology of the area between Alta and the Komagfjord tectonic window is presented. Lithologies (including a tillite) constituting an autochthonous sequence are described from an area on the north-east side of Altafjord, and from their similarity to those of formations occurring in adjacent areas a revised regional stratigraphical correlation is proposed. An occurrence of biogenic structures appears to provide confirmatory evidence for an earlier suggested correlation with Late Precambrian sequences be tween west and east Finnmark. D. Roberts & E. Fareth, Norges Geologiske Undersøkelse, Postboks 3006, 7001 Trondheim, Norway. Regional setting; previous correlations Our. knowledge of the geology of the Alta district of west Finnmark owes much to the work of Holtedahl (1918, 1960) and Føyn (1964). The oldest rocks, the Raipas Group or Series (Reitan 1963a) of Precambrian (Karelian) age, are represented by a sequence of greenschist facies metasediments, metavolcanics and intrusives. Lying unconformably upon the Raipas is a quartzite formation, a thin tillite, and a mixed shale and sandstone succession. Holtedahl (1918) re ferred to these autochthonous post-Raipas rocks as the 'Bossekopavdelingen', but Føyn (1964) later demonstrated the presence of an angular uncon formity beneath the tillite and adopted this break as the border between what he termed the Bossekop Group and the overlying sediments, the Borras Group. These were later referred to as sub-groups (Føyn 1967, Pl.