From Literary Page to Musical Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTIST No TITLE ARTIST

No TITLE ARTIST No TITLE ARTIST 1787 40 Y 20 2022 ACARICIAME J.C.CALDERON 1306 72 HACHEROS PA UN PALO ARSENIO RODRIGUEZ 1301 ACEPTE LA VERDAD SEÑORA SILVIA A.GLEZ 574 A AQUELLA M. A. SOLIS 2070 ACEPTO MI DERROTA LOS BUKIS 395 A BUSCAR MI AMOR JOSE GELABERT 955 ACERCATE MAS EFRAIN LOGROIRA 2064 A CAMBIO DE QUE LUCHA VILLA 629 ACERCATE MAS OSVALDO FARRES 1686 A COGER CANGREJO PABLO CAIRO 1038 ACOMPAÑEME CIVIL J.L.GUERRA 3059 A DONDE VA EL AMOR 1507 ACONSEJEME MI AMIGO LÓPEZ Y GONZALEZ 2640 A DONDE VA NUESTRO AMOR ANGELICA MARIA 157 ACUERDATE DE ABRIL AMAURI PEREZ 3138 A DONDE VAS 1578 ACUERDATE DE ABRIL AMAURY 573 A DONDE VAYAS M. A. SOLIS 940 ADAGIO ALBINONI, PURON 674 A ESA MANUEL ALEJANDRO 589 ADELANTE MARIO J. B. 1034 A GATAS MARY MORIN 1843 ADIOS 1664 A GOZAR CON MI BATA PABLO CAIRO 2513 ADIOS A JAMAICA LOS HOOLIGANS 913 A LA HORA QUE SEA G.DI MARZO 2071 ADIOS ADIOS AMOR LOS JINETES 1031 A LA MADRE MARY MORIN 2855 ADIOS AMOR TE VAS JUAN GABRIEL 2548 A LA ORILLA DE UN PALMAR G.SALINAS 2856 ADIOS CARI O A.A.VALDEZ 1212 A LA ORILLA DEL MAR ESPERON&CORTAZAR 2072 ADIOS DE CARRASCO LUCHA VILLA 578 A LA QUE VIVE CONTIGO ARMANDO M. 2857 ADIOS DEL SOLDADO D.P. 1624 A LA VIRGEN DEL COBRE MARIA TERESA VERA 2073 ADIOS MARIQUITA LINDA M. JIMENEZ 1727 A LO LARGO DEL CAMINO JOSE A CASTILLO 2858 ADIOS MI CHAPARRITA T. NACHO 838 A MAS DE UNO RUDY LA SCALA 3149 ADONIS 4205 A MEDIA LUZ DONATO LENZI 3011 ADORABLE MENTIROSA JUAN GABRIEL 2065 A MEDIAS DE LA NOCHE LUCHA VILLA 630 ADORO MANZANERO 581 A MI GUITARRA JUAN GABRIEL 1947 AFUERA S.HERNANDEZ 2376 A MI MANERA C.FRANCOIS 2387 AGARRENSE DE LAS MANOS EL PUMA 186 A MI PERLA DEL SUR JORGE A. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

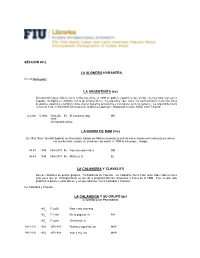

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

From Literary Page to Musical Stage: Writers, Librettists, and Composers of Zarzuela and Opera in Spain and Spanish America (1875-1933)

From Literary Page to Musical Stage: Writers, Librettists, and Composers of Zarzuela and Opera in Spain and Spanish America (1875-1933) Victoria Felice Wolff McGill University, Montreal May 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies © Victoria Felice Wolff 2008 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53325-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-53325-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

An Approach to the Cuban Institutions That Treasure Document Heritage Related to Music

An Approach to the Cuban Institutions that Treasure Document Heritage Related to Music CUBA Obrapía No.509 entre Bernaza y Villegas/Habana Vieja CP10100 Teléfonos: 7861-9846/7 863-0052 Email: [email protected] Lic. Yohana Ortega Hernández Musicologist Head of the Archives and Library Odilio Urfé National Museum of Music 2 The first institution in Cuba which aimed at compiling, studying and disseminating the Cuban music heritage was the Institute for the Research on Folk Music (IMIF), created in 1949 by Odilio Urfé González together with a group of outstanding musicians. In 1963 the Institute became the Seminar for Popular Music (SMP) and in 1989, the Resource and Information Center on Cuban Music Odilio Urfé. In 2002, this institution merged its collections with the collections of the National Museum of Music (MNM) (officially created on September 9, 1971). The MNM is the most important institution in the country dedicated to the conservation, study and dissemination of the Cuban music heritage. Its collections are housed in the Archives and Library Odilio Urfé. Other institutions that in Cuba treasure documents related to music are the National Library José Martí in Havana, the Elvira Cape Library in Santiago de Cuba, the Center for the Research and Development of Cuban Music (CIDMUC); the Alejandro García Caturla Museum in Remedios and the Museum of Music Rodrigo Prats in Sagua la Grande, both in Villa Clara province; the Resource and Information Center on Music Argeliers León in Pinar del Río; the Center for Information and Documentation on Music Rafael Inciarte in Guantánamo and; the Museum of Music Pablo Hernández Balaguer in Santiago de Cuba. -

Bibliografia Cubana

Martí" MINISTERIO DE CULTURA "José BIBLIOGRAFIA CUBANA Nacional Biblioteca Cuba. BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL JOSE MARTI Martí" "José Nacional Biblioteca Cuba. Martí" "José Bibliografía Cubana Nacional Biblioteca Cuba. Martí" "José Nacional Biblioteca Cuba. MINISTERIO DE CULTURA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL JOSE MARTI DEPARTAMENTO DE INVESTIGACIONES BIBLIOGRAFICAS BIBLIOGRAFIA CUBANAMartí" 198 1 "José Nacional BibliotecaTOMO II Cuba. LA HABANA 1983 AÑO DEL X X X ANIVERSARIO DEL MONCADA Martí" "José Nacional Biblioteca Cuba. COMPILADA POR Elena Graupera Juana Ma. Mont TABLA DE CONTENIDO Tabla de siglas y abreviaturas ........................................................ 7 QUINTA SECCION Carteles ............................................................................................... 15 Suplemento .................................................................................... 31 Catálogo de exposiciones ....................................................................Martí" 41 Suplemento .................................................................................... 58 Emisiones postales ................................................................................"José 61 Fonorregistros .................................................................................... 71 Suplemento...................................................................................... 80 Obras musicales ................................................................................ 82 Producción cinematográfica ........................................................... -

De La Zarzuela Española a La Zarzuela Cubana: Vida Del Género En Cuba

L Ángel hzie Vázquez Millares De la zarzuela española a la zarzuela cubana: vida del género en Cuba La investigación acerca del pasado teatral cubano es uno de los Research into Cuban theatrical history is one of (he cloudiest arcas of (he puntos más oscuros de la historiografía de la literatura y el teatro cuba- historiography of Cuban theatre and literature. There is no existing study of nos y, con referencia al caso especial de la zarzuela en Cuba, no existe (he special case of (he zarzuela in Cuba. This historiographical deficiency in ningún estudio monográfico dedicado a ella. Esta carencia historiográfi- no way reflects the historical reality. On the contrary, Cuba presents an in- ca no refleja en absoluto la realidad histórica. Ésta nos presenta, sin tense level of activity relating to zarzuela and dramatic music, which dates embargo, un cuadro con una actividad intensa relativa a la vida lírica y bach to the end of (he eighteenth century. The present article aims to methodi- zarzuelística que tiene sus orígenes a finales del s. XVIII. El presente tra- cally indicate the main lines of (he history of (he zarzuela in Cuba, bajo trata de señalar ordenadamente las líneas maestras por las que emphasizing the existence of two parallel histories: on (he one hand, Spanish discurrió la historia de la zarzuela en Cuba poniendo de relieve la exis- zarzuela in Cuba, whose reception is analysed, and on (he other, properly tencia de dos historias paralelas: por un lado la de la zarzuela española Cuban zarzuela itself. en Cuba, cuya recepción se analiza y, por otro lado, la de la propia zar- zuela cubana. -

PROGRAMA Ernesto Lecuona in Memoriam (125 Años De Su Nacimiento)

MARTES, 29 DE SEPTIEMBRE | 20:00 H – AUDITORIO “ÁNGEL BARJA” TROVA LÍRICA CUBANA Daina Rodríguez_soprano | Ana Miranda_alto | Nadia Chaviano_viola Flores Chaviano_guitarra y dirección PROGRAMA Ernesto Lecuona in memoriam (125 años de su nacimiento) EUSEBIO DELFÍN (1893-1995): Y tú qué has hecho? -bolero JULIO BRITO (1908-1968): El amor de mi bohío –guajira EDUARDO SÁNCHEZ DE FUENTES ELISEO GRENET (1893-1950): (1874-1944): La volanta Negro bembón/N. Guillén -son GONZALO ROIG (1890-1970): EMILIO GRENET (1901-1941): Ojos brujos -fantasía guajira Yambambó /N. Guillén -afro ERNESTINA LECUONA (1882-1951): GILBERTO VALDÉS (1905-1972): Tus besos de pasión -bolero Ogguere - canción de cuna afro MARGARITA LECUONA (1910-1981): RODRIGO PRATS (1909-1980): Babalú -motivo afrocubano Una Rosa de Francia -criolla bolero María Bailén: Chacone –romanza ERNESTO LECUONA (1895-1961): Aquella Tarde -criolla-bolero MOISÉS SIMONS (1889-1945): Siboney -tango congo El manisero -pregón María la O -romanza TROVA LÍRICA CUBANA rova Lírica Cubana fue fundada en España en 1992. Desde Manzanares el Real; Universidad de Salamanca; Festival Inter- entonces ha ofrecido recitales en numerosas instituciones: nacional Andrés Segovia, Fundación Botín de Santander o Casa Instituto Cervantes, Our Lady of Good Church de Nueva de Cantabria, y en ciudades como Florencia, Barcelona, Valencia, York, Centro Cultural Español de Miami; Centro Cultural de la Vi- Segovia, San Lorenzo del Escorial, Aranjuez o Gijón. lla, Centro Cultural Conde Duque, Sala Galileo, Casa del Reloj, Sa- cristía de los Caballeros de Santiago, Ateneo de Madrid; Clásicos Desde su fundación ha centrado su trabajo en la difusión en Verano de la Comunidad de Madrid, Castillo de Los Mendoza, del repertorio más selecto de la canción lírica cubana. -

Roberto González Echevarría

REVISTA de fiesta / Jesús Díaz • 3 tres notas sobre la transición Emilio Ichikawa • 5 s.o.s. por la naturaleza cubana encuentro Carlos Wotzkow • 16 DE LA CULTURA CUBANA el puente de los asnos / Miguel Fernández • 24 Director Jesús Díaz I En proceso I Redacción literatura, baile y béisbol en el (último) fin de Manuel Díaz Martínez siglo cubano / Roberto González Echevarría • 30 Luis Manuel García Iván de la Nuez III Rafael Zequeira música y nación / Antonio Benítez Rojo • 43 Edita derrocamiento / José Kozer • 55 Asociación Encuentro de la Cultura Cubana la crisis invisible: la política cubana en la década c/ Luchana 20, 1º Int. A de los noventa / Marifeli Pérez-Stable • 56 28010 • Madrid inscrito en el viento / Jesús Díaz • 66 Teléf.: 593 89 74 • Fax: 593 89 36 E-mail: [email protected] I Textual I Coordinadora Margarita López Bonilla palabras de saludo a juan pablo ii pronunciadas Colaboradores por monseñor pedro meurice estiú, arzobispo de Juan Abreu • José Abreu Felippe • santiago de cuba, en la misa celebrada en esa Nicolás Abreu Felippe • Eliseo Alberto • Carlos Alfonzo † • Rafael Almanza • ciudad el 24 de enero de 1998 • 71 Alejandro Aragón • Uva de Aragón • Reinaldo Arenas † • René Ariza † • Guillermo Avello Calviño • Gastón Baquero † • el catolicismo de lezama lima Carlos Barbáchano • Jesús J. Barquet • Fidel Sendagorta • 73 Victor Batista • Antonio Benítez Rojo • Beatriz Bernal • Elizabeth Burgos • Madeline Cámara • Esteban Luis Cárdenas • Josep M. Colomer • Orlando Coré • Carlos A. Díaz • Josefina de Diego • I La mirada del otro I Reynaldo Escobar • María Elena Espinosa • Tony Évora • Lina de Feria • Miguel Fernández • Gerardo Fernández Fe • Reinaldo García Ramos • después de fidel, ¿qué? / Josep M. -

Darseth Irasema Fernández Bobadilla

UNIVERSIDAD PEDAGÓGICA NACIONAL UNIDAD AJUSCO “LA TELENOVELA COMO FACTOR IMPORTANTE DE LA EDUCACIÓN EN LAS FAMILIAS MEXICANAS (1958-2000)” T E S I N A PARA OBTENER EL TITULO DE: LICENCIADO EN PEDAGOGÍA P R E S E N T A : DARSETH IRASEMA FERNÁNDEZ BOBADILLA ASESOR: DAVID CORTÉS ARCE MÉXICO D.F., 2004 INDICE Pág. INTRODUCCIÓN 1 CAPÍTULO I CONCEPTOS 4 1.1. EDUCACIÓN 4 1.2. FAMILIA 5 1.3. MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN 6 1.3.1. Televisión 7 1.4. TELENOVELA 10 CAPÍTULO II 1951-1960. LOS INICIOS (GUTIERRITOS) 12 2.1. CONTEXO SOCIO-POLÍTICO 12 2.2. PRINCIPALES TELENOVELAS TRANSMITIDAS EN MÉXICO 16 2.3. INFLUENCIA DE GUTIERRITOS EN LA EDUCACIÓN FAMILIAR DE ESA DÉCADA 20 CAPÍTULO III 1961-1970. ENTRE LA HISTORIA Y LAS ROSAS (SIMPLEMENTE MARÍA) 23 3.1. CONTEXTO SOCIO POLÍTICO 23 3.2. PRINCIPALES TELENOVELAS TRANSMITIDAS EN MÉXICO 28 3.3. INFLUENCIA DE SIMPLEMENTE MARIA EN LA EDUCACIÓN FAMILIAR DE ESA DÉCADA 32 CAPÍTULO IV 1971-1980. DE LA INOCENCIA A LA MARGINACIÓN (MUNDO DE JUGUETE) 36 4.1. CONTEXTO SOCIO-POLÍTICO 36 4.2. PRINCIPALES TELENOVELAS TRANSMITIDAS EN MÉXICO 41 4.3. INFLUENCIA DE MUNDO DE JUGUETE EN LA EDUCACIÓN FAMILIAR DE ESA DÉCADA 47 CAPÍTULO V 1981-1990. EMBRUJO Y SEDUCCIÓN (QUINCEAÑERA) 50 5.1. CONTEXTO SOCIO-POLÍTICO 50 5.2. PRINCIPALES TELENOVELAS TRANSMITIDAS EN MÉXICO 52 5.3. INFLUENCIA DE QUINCEAÑERA EN LA EDUCACIÓN FAMILIAR DE ESA DÉCADA 59 CAPÍTULO VI 1991-2000. DE LA ONDA AL CAMBIO (MIRADA DE MUJER) 62 6.1. CONTEXTO SOCIO-POLÍTICO 62 6.2. -

Telenovelas De La Década De 1980 Esta Es La Lista De Todas Las Novelas Producidas En Esa Década: • Verónica 1981 • Toda U

Telenovelas de la década de 1980 Esta es la lista de todas las novelas producidas en esa década: 1980 1981 1982 • • Al final del arco • Espejismo El amor nunca iris • Extraños muere • • Al rojo vivo caminos del amor Chispita • • Ambición • El hogar que yo Déjame vivir • Aprendiendo a robé • El derecho de amar • Infamia nacer • • El árabe • Juegos del En busca del • Caminemos destino Paraíso • • Cancionera • Una limosna de Gabriel y • Colorina amor Gabriela • • El combate • Nosotras las Lo que el cielo • Conflictos de un mujeres no perdona • médico • Por amor Mañana es • Corazones sin • Quiéreme siempre primavera • rumbo • Toda una vida Vanessa • Juventud • Vivir • Lágrimas de amor enamorada • No temas al amor • Pelusita • Querer volar • Sandra y Paulina • Secreto de confesión • Soledad • Verónica 1983 1984 1985 • Amalia Batista • Los años felices • Abandonada • El amor ajeno • Aprendiendo a • El ángel caído • Bianca Vidal vivir • Angélica • Bodas de odio • Eclipse • Los años pasan • Cuando los hijos • Guadalupe • Esperándote se van • La pasión de • Juana Iris • La fiera Isabela • Tú o nadie • El maleficio • Principessa • Vivir un poco • Un solo corazón • Sí, mi amor • Soltero en el aire • Te amo • La traición • Tú eres mi destino 1986 1987 1988 • Ave Fénix • Los años • Amor en silencio • El camino perdidos • Dos vidas secreto • Como duele • Dulce desafío • Cautiva callar • Encadenados • Cicatrices del • La indomable • El extraño alma • Pobre señorita retorno de Diana • Cuna de lobos Limantour Salazar • De pura sangre • El precio de la -

Seccion 03 L

LOS ANGLOPERSAS((¿) 1930 Brunsw 41206 Lamento africano EL 1930 Brunsw 41206 El manisero MS LOS ARAGÓN(Me?) 1961 Dimsa 45-4249 Sacuchero de la Habana 1961 Mus 4298 Guantanamera JF ORQ. LOS ARMÓNICOS (ve) Lp Discolando 8096 (con licencia Discomoda, ve) “La tachuela – Orq. Los Armónicos” Incluímos los números cantados por Manolo Monterrey (MM); Osvaldo Rey (OR) y Frank Rivas (FR). ca.196_. La tachuela / paseito E. Herrera MM Contigo en la distancia / b CPL OR Pasillaneando / tn La Riva MM Mosaico: Dónde está Miguel, MM,OR, Arrebatadora. FR Mosaico de merengues MM,OR, FM De corazón a corazón / b FM OR Mosaico de congas: Los MM componedores, Una dos y tres, Carnaval de Oriente, La conga se va. TRÍO LOS ASES(Me) 1952 rca 23-5960 Me Comienzo GU 1952 rca 23-5960 Me Juana Reverbero GU 1953 rca 75-1927 Me Contigo en la distancia/c CPL 1953 rca 75-8951 Me Comienzo GU 1953 rca 75-8951 Me Juana Reverbero GU 1953 rca 23-6154 Me Contigo en la distancia CPL 1 1953 rca 23-6154 Me Mil congojas JPM 1955 rca 23-6964 Me Sufre mas JAM 1954 rca 75-9452 Me Yo sabía que un día/ch Ant.Sánchez 1954 rca 75-9452 Me Yo no camino mas/ch N.Mondejar 1955 rca 23-6566 Me Yo no camino más/ch N.Mondéjas 1955 rca 23-6595 Me Tú mi adoración JAM 1955 rca 75-9497 Me Tú mi adoración JAM 1955 rca 75-9830 Me Sufre mas JAM 1955 rca 23-6668 Me Rico Vacilón RRuiz jr 1955 rca 23.6668 Me Para que tu lo bailes Fellove 1955 rca 75-9552 Me Para que tu lo bailes Fellove 1955 rca 23-6682 Me Nuestra cobardía JAM 1955 rca 75-9571 Me Nuestra cobardía JAM 1955 rca 23-6911 Me Delirio CPL 1955 rca 75-7980 Me Delirio CPL 1955 rca 75-9552 Me Rico vacilón/ch RRjr 1956 rca 76-0050 Me Tu me acostumbraste/c FD 1958 rca 23-7220 Me Tu me acostumbraste/c FD 1957 rca 79-0205 Me Mil congojas JPM 1957 rca 23-7430 Realidad y fantasía/c CPL CONJUNTO LOS ASTROS Ver: Conjunto René Álvarez TRIO LOS ASTROS (Me) 195? Vik 45-0240 Me Inolvidable/b JG TRIO LOS ATÓMICOS (Me) 1949 Pee 3037 Me Amor de media noche OS 1950 Pee 3143 Me Afrodita GU LOS BAMBUCOS (ar) (orq. -

The Origin and Development of Cuban Popular Music Genres And

THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF CUBAN POPULAR MUSIC GENRES AND THEIR INCORPORATION INTO ACADEMIC COMPOSITIONS by ALEJANDRO EDUARDOVICH FERREIRA (Under the Direction of Levon Ambartsumian) ABSTRACT In the sixteenth century, Cuba became the host of two very diverse and different cultures. Here, European and African traditions met on a neutral ground where the interchange of rhythms, melodies, and musical forms became inevitable. Over the centuries, this mutual interaction gave birth to genres such as the contradaza, danza, danzón, son, conga, habanera, güajira, criolla, and trova. Despite the fact that these genres were born as dance and popular music, their rhythms and style started to be incorporated into the most refined realm of academic compositions. The purpose of this study is to explain the origin and evolution of the above mentioned genres. Moreover, with the aid of the accompanying recording, I will explain how some Cuban composers participated in the creation and development of these genres. Furthermore, I will show how some other composers where influenced by these genres and the way in which these genres were incorporated in their compositions. INDEX WORDS: Cuban Music, Academic Cuban Compositions, Violin and Piano, Cuban Duo, contradaza, danza, danzón, son, conga, habanera, güajira, criolla, trova THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF CUBAN POPULAR MUSIC GENRES AND THEIR INCORPORATION INTO ACADEMIC COMPOSITIONS by ALEJANDRO EDUARDOVICH FERREIRA MASCARO B.M., Peruvian National Conservatory, Peru 1997 M.M., The University of Southern