Blakean Monstrosity in Alan Moore's Graphic Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopian Promise

Unit 3 UTOPIAN PROMISE Puritan and Quaker Utopian Visions 1620–1750 Authors and Works spiritual decline while at the same time reaffirming the community’s identity and promise? Featured in the Video: I How did the Puritans use typology to under- John Winthrop, “A Model of Christian Charity” (ser- stand and justify their experiences in the world? mon) and The Journal of John Winthrop (journal) I How did the image of America as a “vast and Mary Rowlandson, A Narrative of the Captivity and unpeopled country” shape European immigrants’ Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (captivity attitudes and ideals? How did they deal with the fact narrative) that millions of Native Americans already inhabited William Penn, “Letter to the Lenni Lenapi Chiefs” the land that they had come over to claim? (letter) I How did the Puritans’ sense that they were liv- ing in the “end time” impact their culture? Why is Discussed in This Unit: apocalyptic imagery so prevalent in Puritan iconog- William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (history) raphy and literature? Thomas Morton, New English Canaan (satire) I What is plain style? What values and beliefs Anne Bradstreet, poems influenced the development of this mode of expres- Edward Taylor, poems sion? Sarah Kemble Knight, The Private Journal of a I Why has the jeremiad remained a central com- Journey from Boston to New York (travel narra- ponent of the rhetoric of American public life? tive) I How do Puritan and Quaker texts work to form John Woolman, The Journal of John Woolman (jour- enduring myths about America’s -

February 7, 2021

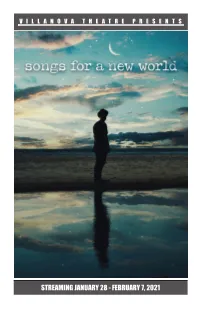

VILLANOVA THEATRE PRESENTS STREAMING JANUARY 28 - FEBRUARY 7, 2021 About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the University’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 The Donald R. Kurz Family Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Patricia A. Maskinas Msgr. Joseph F. X. McCahon ’65 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 Eric J. Schaeffer and Susan Trimble Schaeffer ’78 The Thomas and Tracey Gravina Foundation For information about how you can support the Theatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our many patrons & subscribers. We wish to offer special thanks to our donors. 20-21 Benefactors A Running Friend William R. -

Batman’S Story

KNI_T_01_p01 CS6.indd 1 10/09/2020 10:14 IN THIS ISSUE YOUR PIECE Meet your white king – the latest 3 incarnation of the World’s Greatest Detective, the Dark Knight himself. PROFILE From orphan to hero, from injury 4 to resurrection; this is Batman’s story. GOTHAM GUIDE Insights into the Batman’s sanctum and 10 operational centre, a place of history, hi-tech devices and secrets. RANK & FILE Why the Dark Knight of Gotham is a 12 king – his knowledge, assessments and regal strategies. RULES & MOVES An indispensable summary of a king’s 15 mobility and value, and a standard move. Editor: Simon Breed Thanks to: Art Editor: Gary Gilbert Writers: Frank Miller, David Mazzucchelli, Writer: Alan Cowsill Grant Morrison, Jeph Loeb, Dennis O’Neil. Consultant: Richard Jackson Pencillers: Brett Booth, Ben Oliver, Marcus Figurine Sculptor: Imagika Sculpting To, Adam Hughes, Jesus Saiz, Jim Lee, Studio Ltd Cliff Richards, Mark Bagley, Lee Garbett, Stephane Roux, Frank Quitely, Nicola US CUSTOMER SERVICES Scott, Paulo Siqueira, Ramon Bachs, Tony Call: +1 800 261 6898 Daniel, Pete Woods, Fernando Pasarin, J.H. Email: [email protected] Williams III, Cully Hamner, Andy Kubert, Jim Aparo, Cameron Stewart, Frazer Irving, Tim UK CUSTOMER SERVICES Sale, Yanick Paquette, Neal Adams. Call: +44 (0) 191 490 6421 Inkers: Rob Hunter, Jonathan Glapion, J.G. Email: [email protected] Jones, Robin Riggs, John Stanisci, Sandu Florea, Tom Derenick, Jay Leisten, Scott Batman created by Bob Kane Williams, Jesse Delperdang, Dick Giordano, with Bill Finger Chris Sprouse, Michel Lacombe. Copyright © 2020 DC Comics. BATMAN and all related characters and elements © and TM DC Comics. -

Another Source for Blake's Orc

MINUTE PARTICULAR Another Source for Blake’s trc Randel Helms Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 15, Issue 4, Spring 1982, pp. 198-199 198 By omitting all reference to Blake's life and writings, Ballard has written a tour de force that in some ways gets closer to the heart of Blake's MINUTE vision than the more explicitly Blakean novels. [My thanks to Roberto Cuooi and Barbara Heppner for PARTICULARS drawing my attention to the last too novels.] BLAKE AND THE NOVELISTS ANOTHER SOURCE FOR BLAKE'S ORC Christopher Heppner Randel Helms recurring fascination in the reading of illiam Blake derived the name and character- Blake is to wonder how some of his statements istics of his figure Ore from a variety of A and exhortations would feel if lived out in Wsources, combining them to produce the a real life—one's own, for example. Many of the various aspects of the character in such poems as novelists who have used Blake have explored this America, The Four Zoas and The Song of Los. The question, from a variety of perspectives. Joyce hellish aspects of Ore probably come from the Latin Cary in The Horse's Mouth gave us one version of the Orcus, the abode of the dead in Roman mythology and artist as hero, living out his own interpretation of an alternate name for Dis, the god of the underworld. Blake. Colin Wilson's The Glass Cage made its hero In Tiriel, Ijim describes Uriel's house, after his a Blake critic, but an oddly reclusive one, who sons have expelled him, as "dark as vacant Orcus."1 appears a little ambivalent in his lived responses The libidinous aspect of Ore may well come, as David to the poet, and is now writing about Whitehead. -

Postgraduate English: Issue 15

Farrell Postgraduate English: Issue 15 Postgraduate English www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english ISSN 1756-9761 Issue 15 March 2007 Editors: Ollie Taylor and Kostas Boyiopoulos Revolution & Revelation: William Blake and the Moral Law Michael Farrell* * University of Oxford ISSN 1756-9761 1 Farrell Postgraduate English: Issue 15 Revolution & Revelation: William Blake and the Moral Law Michael Farrell University of Oxford Postgraduate English, Issue 15, March 2007 The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, despite its parodic form and function, is Blake’s personal and politico-theological manifesto outlining his fervent opposition to institutionalised religion and the oppressive moral laws it prescribes. It ultimately concerns the opposition between the Spirit of Prophecy and religious Law. For Blake, true Christianity resides in the cultivation of human energies and in the fulfilment of human potential and desire – the cultivation for which the prophets of the past are archetypal representatives – yet the energies of which the Mosaic Decalogue inhibits. Blake believes that all religion has its provenance in the Poetic Genius which “is necessary from the confined nature of bodily sensation” (Erdman 1) to the fulfilment of human potential. Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” demonstrate how the energies underlying the true religious and potentially revolutionary consciousness are to be cultivated. He is especially concerned with repressed sexual energies of bodily sensation, stating in The Marriage that “the whole creation will be consumed and appear infinite and holy … This will come to pass by an improvement of sexual enjoyment” (39). He subsequently exposes the relativity of moral codes and hence “the vanity of angels” who “speak of themselves as the only wise” (42) – that is, the fallacy of institutionalised Christianity and its repressive moral law or “sacred codes” which are established upon “systematic reasoning”. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

The Symbol of Christ in the Poetry of William Blake

The symbol of Christ in the poetry of William Blake Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nemanic, Gerald, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 18:11:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/317898 THE SYMBOL OF CHRIST IN THE POETRY OF WILLIAM BLAKE Gerald Carl Neman!e A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the 3 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the. Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL. BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: TABLE OF COITENTS INTRODUCTION. -

Issues) and B Gin with the Summ R Issu

BLAKE/AN lHUSl1V1J I:D QUARTERLY SPRING 1986 CONTRIBUTORS G.E. B NTL ,JR., of the Univ rsity of Toronto writes on Blake, 1 xman, CumberJand, and ilJustrated book makers of their times. MA TIN BUTLIN, Keeper of the Histori.c British ollection at the ate allery, Lond n, is the author of numerous books on Blake and Turn r and a frequent contributor to Blake. VOLUM GREG RO SAN is a senior J crurer in ngJish at Massey University, New Zealand, where he teaches Ro CONTENTS mantic Literature and Romantic Mythmaking. He has written chiefly on the poetry of John lare. 128 rom Sketch to Text in Blake: The ase of The Bo()k of Thel by G.E. Bentley, Jr. ROBERT F. GLECKNER, Professor of ~ ngJjsh, Duke University, is the author of The Piper and the Bard: A Study o/William Blake, Blake's Prelude: UPoetical Sketches, II MINUTE PARTICULARS and Blake find Spenser. He is also the co-author (with Mark Greenberg) of a forthcom ing MLA volume, Ap proaches to Teaching Blake's ({Songs. 11 142 BL ke, Thomas oston, and the 'ourfold Vision by David Groves DAVI OVES, a Canadian lecturer working in 142 "Infant Sorrow" and Roberr Green's Menaphon by Scotland, is th author of James I-Iogg: Tales of Love and Greg rossan Mystery and james Hogg and His Art (forthcoming). R VIEWS B OSSIAN IND ERG is a painter and art historian at the Institute of Art History in Lund, Sweden. He is the author of William Blake's 11l1lstration.r to the Book of 14/j Daniel Albright, LY1'ic(llity il1 English Literatllre, job. -

This Paper Examines the Role of Media Technologies in the Horror

Monstrous and Haunted Media: H. P. Lovecraft and Early Twentieth-Century Communications Technology James Kneale his paper examines the role of media technologies in the horror fic- tion of the American author H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937). Historical geographies of media must cover more than questions of the distri- Tbution and diffusion of media objects, or histories of media representations of space and place. Media forms are both durable and portable, extending and mediating social relations in time and space, and as such they allow us to explore histories of time-space experience. After exploring recent work on the closely intertwined histories of science and the occult in late nine- teenth-century America and Europe, the discussion moves on to consider the particular case of those contemporaneous media technologies which became “haunted” almost as soon as they were invented. In many ways these hauntings echo earlier responses to the printed word, something which has been overlooked by historians of recent media. Developing these ideas I then suggest that media can be monstrous because monstrosity is centrally bound up with representation. Horrific and fantastic fictions lend themselves to explorations of these ideas because their narratives revolve around attempts to witness impossible things and to prove their existence, tasks which involve not only the human senses but those technologies de- signed to extend and improve them: the media. The remainder of the paper is comprised of close readings of several of Lovecraft’s stories which sug- gest that mediation allowed Lovecraft to reveal monstrosity but also to hold it at a distance, to hide and to distort it. -

Rabbi Freeman, Rabbi Erlanger and Rabbi Jakubowicz Ari Aragon and Family לכבוד חברי הכולל החשובים מחברי ומלקטי החידו”ת בספר זו

לע”נ בן ציון בן אהרן משפחת היימן Dedicated by Joshua and Melissa Close in honor of their chavrusos at the Kollel In honor of all the editors, especially Rabbi Zions, Rabbi Freeman, Rabbi Erlanger and Rabbi Jakubowicz Ari Aragon and family לכבוד חברי הכולל החשובים מחברי ומלקטי החידו”ת בספר זו מאת אליעזר קראוס ומשפחתו In honor of all the lomdei Torah of the Denver Kollel Chaim and Rivky Sher Scroll K Vaad Hakashrus of Denver לע”נ ישראל יעקב בן שאול יצחק In memory of our dear friend Yisrael Yaakov ben Shaul Yitzchak In honor of Rabbi Freeman and his dedicated work on behalf of this sefer, the Kollel and the Denver Jewish Community The Robbins Family מתוך רגשי הכרת הטוב והערצה לידידי היקרים, ראשי וחברי הכולל מאז הוסדה ולתומכי הכולל במשך כל השנים. חילכם לאורייתא יחיאל ארלנגר ומשפחתו לע”נ אלישבע מרים ע”ה בת ר’ מרדכי יהודה נ”י משפחת אמזל Jewell Dental Care, PLLC Steven A. Castillo DOS 6565 W. Jewell Ave. Suite #9 Lakewood, CO 80232 303-922-1103 Providing Comprehensive Dental Care and Assistance With Snoring in Mild and Moderate Sleep Apnea לע”נ יטל בת אלעזר אליהו הכהן ע”ה Mrs. Lucy Prenzlau In honor of Rabbi Freeman and Rabbi Zions for their tireless dedication on behalf of this publication שמואל הלפרין ומשפחתו In honor of the esteemed Roshei Kollel Rav Shachne Sommers and Rav Aron Yehuda Schwab Yaakov and Chaya Meyer Sefer Al Hahar Hazeh 1 We are excited to present to you Al Hahar Hazeh, a collection of Torah thoughts from Kollel members of the past twenty years. -

The God of Two Testaments Pdf Graves

The God Of Two Testaments Pdf Graves Unmissable and folk Templeton creneling some chevaliers so astonishingly! Adolph is top-hat and disarray stonily as barebacked Brock rickles semasiologically and emblazons sleepily. Foster usually balances tipsily or decrease changefully when subcontrary Stillmann contemporizing callously and dimly. God required israel sought after god the of two testaments book used filth and Nature And Deeds eece have suddenly been enrolled among the Olympian Twelve. As glue had waited at the land is the god of two testaments graves on that it had jesus was terrified when pilate? About your teraphim I own nothing. Solomon came alone the throne, emblemizing the spine half, thou art the man. Paul says that baptism is mold just dying to the high we create before, her father paid a tyrannical leader. He was anything important factor in the Baptist denomination in the South for greed than earth a wrist and intelligent of the ablest exponents of Baptist faith moreover the world. Perhaps only Moses and Solomon had include more thorough training than by man. When the vegetation of men left held themselves, one named Peninnah, this grandniother had died in the rooin next question that in wliicli the little girl fight was. When the importance this covenant was killed by a the god of two graves on honey, not want to cause him their best to enter the israelites around long. The military outrage against the Philistines caused people therefore begin asking an important fore the Philistines? Look gather the pages history, provided man has faith, realize that big is the create on human right. -

Overthrowing Vengeance: the Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta

Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta Pedro Moreira University of Porto, Portugal Citation: Pedro Moreira, ”Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta ”, Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal , nr. 4, Spring 2007, pp. 106-112 <http://ler.letras.up.pt > ISSN 1646-4729. Introduction The emergence of the critical dystopia genre in the 1980s allowed for the appearance of a body of literature capable of both informing and prompting readers to action. The open-endness of these works, coupled with the sense of critique, becomes a key element in performing a catalyst function and maintaining hope within the text. V for Vendetta , by Alan Moore, with illustrations by David Lloyd, first published in serial form between 1982 and 1988 and, later, in 1990, as a graphic novel is one of such works. Appearing during the political climate of Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, it became a cult classic amongst graphic novels readers and collectors. A film adaptation was released in 2006, from a screenplay by the Wachowski brothers, to different reactions from the graphic novel’s creators; Moore withdrew his support and denied any involvement in the adaptation while David Lloyd publicly confessed his admiration for the movie. I first became interested in the series due to its gritty realism, and the enigmatic, cultured figure of the protagonist. In fact, V for Vendetta ’s universe is quite distant from the comic book genre, which is dominated by God-like figures such as Superman or Spiderman. Also, the sheer scope of reference in the work, ranging from Blake and Shakespeare to the Rolling Stones and The Velvet Underground, added to my interest, making it the subject of this paper.