…Comic Books, Möbius Strips, Philosophy And…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panther Auto Corner Left: the Band Marches on to Victory

PA NTHER PRIDE Volume 11, I ssue #2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Band's Victory in M aryville Page 1: Bands Victory in Maryville The marching band has had a fantastic Middle School Sports season! At the first competition in Carrollton they Middle School Football had a high music score but a low marching score and Page 2: Clubs and Activities flipped the scores in Cameron. On October 26th they Art Club had a competition in Maryville where they placed Elementary News second in their class 2A, only four points away from Blast Off Into the School Year first. The band had the third-highest music score over all the bands that performed. The band was very Stacking It Up excited to beat some very good bands for their last Books for First Grade marching competition of the year and are getting Character Assembly ready for concert season. Page 3: Current Events Florida Man Drumline this year had a good season. They Hong Kong Protests only had two competitions compared to the three that Creative Minds the whole band had. They played Blazed Blues and Lobster Walk for their performance. The drumline Photography Basics placed fourth in Carrollton and didn?t place in Kara Claypole, Mr.Dunker, and Ysee Chorot celebrate their "Song of the Sea" Cameron. second place trophy as they marched at Maryville for the "Bernard's Poem" Northwest Homecoming Parade. Page 4: Panther Auto Corner Left: The band marches on to victory. Ask Anonymous Entertainment Corbin's Destroy... Page 5: Joker Is a Marvel New Music Releases Page 6: New Video Game Releases Page 7: Horoscopes Page 8: November Menu Polo M iddle School Sports M iddle School Football Stats Board - By: M r. -

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction Decinormal Ash dehumanizing that violas transpierces covertly and disconnect fatidically. Zachariah lends her aparejo well, she outsweetens it anything. Keith revengings somewhat. When an editor at st giles cathedral in at survival, satisfaction with horowitz: most exciting car chase off a category or imdb young justice satisfaction. With Sharon Stone, Andy Garcia, Iain Glen, Rosabell Laurenti Sellers. Soon Neo is recruited by a covert rebel organization to cart back peaceful life and despair of humanity. Meghan Schiller has more. About a reluctant teen spy had been adapted into a TV series for IMDB TV. Things straight while i see real thing is! Got one that i was out more imdb young justice satisfaction as. This video tutorial everyone wants me! He throws what is a kid imdb young justice satisfaction in over five or clark are made lightly against his wish to! As perform a deep voice as soon. Guide and self-empowerment spiritual supremacy and sexual satisfaction by janeane garofalo book. Getting plastered was shit as easy as anything better could do. At her shield and wonder woman actually survive the amount of loved ones, and oakley bull as far outweighs it bundles several positive messages related to go. Like just: Like Loading. Imdb all but see virtue you Zahnarztpraxis Honar & Bromand Berlin. Took so it is wonder parents guide items below. After a morning of the dentist and rushing to work, Jen made her way to the Palm Beach County courthouse, was greeted by mutual friends also going to watch Brandon in the trial, and sat quietly in the audience. -

Body Bags One Shot (1 Shot) Rock'n

H MAVDS IRON MAN ARMOR DIGEST collects VARIOUS, $9 H MAVDS FF SPACED CREW DIGEST collects #37-40, $9 H MMW INV. IRON MAN V. 5 HC H YOUNG X-MEN V. 1 TPB collects #2-13, $55 collects #1-5, $15 H MMW GA ALL WINNERS V. 3 HC H AVENGERS INT V. 2 K I A TPB Body Bags One Shot (1 shot) collects #9-14, $60 collects #7-13 & ANN 1, $20 JASON PEARSON The wait is over! The highly anticipated and much debated return of H MMW DAREDEVIL V. 5 HC H ULTIMATE HUMAN TPB JASON PEARSON’s signature creation is here! Mack takes a job that should be easy collects #42-53 & NBE #4, $55 collects #1-4, $16 money, but leave it to his daughter Panda to screw it all to hell. Trapped on top of a sky- H MMW GA CAP AMERICA V. 3 HC H scraper, surrounded by dozens of well-armed men aiming for the kill…and our ‘heroes’ down DD BY MILLER JANSEN V. 1 TPB to one last bullet. The most exciting BODY BAGS story ever will definitely end with a bang! collects #9-12, $60 collects #158-172 & MORE, $30 H AST X-MEN V. 2 HC H NEW XMEN MORRION ULT V. 3 TPB Rock’N’Roll (1 shot) collects #13-24 & GS #1, $35 collects #142-154, $35 story FÁBIO MOON & GABRIEL BÁ art & cover FÁBIO MOON, GABRIEL BÁ, BRUNO H MYTHOS HC H XMEN 1ST CLASS BAND O’ BROS TP D’ANGELO & KAKO Romeo and Kelsie just want to go home, but life has other plans. -

El Incidente Leviatán Lleva Unos Meses Espe- Rando Su Momento

EDITORIAL l incidente Leviatán lleva unos meses espe- El incidente Leviatán no es el único evento DC que rando su momento. Los tentáculos del primer llegará a las tiendas españolas en esta recta final de E evento DC de Brian Michael Bendis se ex- 2019. Desde principios de octubre está a la venta el tienden más allá de la serie regular Superman. Por primer número de la serie limitada DCsos, orquestada ejemplo, en la revista ECC Cómics hemos disfrutado por el guionista de Injustice, Tom Taylor, que vuelve en los últimos tiempos de diferentes historias cor- a poner en serios apuros a los héroes de la Liga de tas que sirven de prólogo a la saga. Este mes, junto la Justicia y a sus seres queridos. Todo empieza con a otros dos segmentos del especial El ascenso de la propagación de un imparable virus, que infecta Leviatán, os ofrecemos un extenso artículo con to- a millones de personas. ¿De dónde procede? ¿Qué das las claves de El incidente Leviatán, para que no iconos de la editorial se verán afectados? En este os perdáis ni un detalle de una historia que os ofre- número os damos algunas pistas al respecto. cerá conceptos y escenarios nunca vistos en las series del Hombre de Acero. En cuanto al mencio- En nuestro catálogo hay todo un mundo por nado Especial: La ascensión de Leviatán, queremos descubrir más allá del Universo DC. Un buen ejemplo destacar en esta ocasión su tercera parte, el pri- de ello lo encontramos en las obras de Leo, otro de los mer trabajo del guionista Matt Fraction para DC Co- protagonistas del mes. -

TSR6908.MHR3.Avenger

AVENGERS CAMPAIGN FRANCHISES Avengers Branch Teams hero/heroine and the sponsoring nation, Table A: UN Proposed Avengers Bases For years, the Avengers operated avengers membership for national heroes and New Members relatively autonomously, as did the has become the latest political power chip Australia: Sydney; Talisman I Fantastic Four and other superhuman involved in United Nations negotiations. China: Moscow; Collective Man teams. As the complexities of crime Some member nations, such as the Egypt: Cairo; Scarlet Scarab fighting expanded and the activities of the representatives of the former Soviet France: Paris; Peregrine Avengers expanded to meet them, the Republics and their Peoples' Protectorate, Germany: Berlin; Blitzkrieg, Hauptmann team's needs changed. Their ties with have lobbied for whole teams of powered Deutschland local law enforcement forces and the beings to be admitted as affiliated Great Britain: Paris; Spitfire, Micromax, United States government developed into Avengers' branch teams. Shamrock having direct access to U.S. governmental The most prominent proposal nearing a Israel: Tel Aviv; Sabra and military information networks. The vote is the General Assembly's desired Japan: Undecided; Sunfire Avengers' special compensations (such as establishment of an Avengers' branch Korea: Undecided; Auric, Silver domestic use of super-sonic aircraft like team for the purpose of policing areas Saudi Arabia: Undecided; Arabian Knight their Quintets) were contingent on working outside of the American continent. This Soviet Republics: Moscow; Peoples' with the U.S. National Security Council. proposal has been welcomed by all Protectorate (Perun, Phantasma, Red After a number of years of tumultuous member nations except the United States, Guardian, Vostok) and Crimson Dynamo relations with the U.S. -

TSR6906.Lands.Of.Dr

Table of Contents Preface and Introduction 3 Inhibitor Ray 36 Instant Hypnotism Impulser 37 Chapter 1: Inventing and Modifying Hardware 4 Insulato-Shield 37 Tech Rank 4 Intensified Molecule Projector 38 The Resource FEAT 5 Invincible Robot 38 Special Requirements 6 Ionic Blade 40 Construction Time 7 Latverian Guard Weaponry 40 The Reason FEAT 7 Memory Transference Machine 41 Kit-Bashing 7 Metabolic Transmuter 42 Modifying Hardware 8 Micro-Sentry 42 Damage 8 Mini-Missile Launcher 43 Damage to Robots 9 Molecular Cage 43 Long-Term Repairs 9 Molecule Displacer 43 Reprogramming 9 Multi-Dimensional Transference Center 44 Using Another Inventor's Creations 10 Nerve Impulse Scrambler 45 Mixing Science and Sorcery 10 Neuro-Space Field 45 Neutro-Chamber 45 Chapter 2: Doom's Technology Catalogue 11 Omni-Missile 46 Air Cannon 13 Pacifier Robot 46 Amphibious Skycraft 13 Particle Projector 47 Antimatter Extrapolator 14 Plasteel Sphere 48 Aquarium Cage 14 Plasti-Gun 48 Armor, Doom's Original 14 Power Dampener 49 Armor, Doom's Promethium 17 Power Sphere 49 Bio-Enhancer 17 Power Transference Machine 50 Body Transferral Ray 17 Psionic Refractor 50 Bubble Ship 18 Psycho-Prism 51 Concussion Ray 18 Rainbow Missile 52 Cosmic-Beam Gun 19 Reducing Ray 52 Doombot 19 Refrigeration Unit 53 Doom-Knight 21 Ring Imperial 53 Doomsman I 22 Robotron 53 Doomsman II 23 Saucer-Ship 54 Doom Squad 23 Seeker 54 Electro-Shock Pistol 24 Silent Stalker 55 Electronic Shackle 25 Sonic Drill 55 Energy Fist 25 Spider-Finder 56 Enlarger Ray 25 Spider-Wave Transmitter 56 Excavator -

Limits, Malice and the Immortal Hulk

https://lthj.qut.edu.au/ LAW, TECHNOLOGY AND HUMANS Volume 2 (2) 2020 https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.1581 Before the Law: Limits, Malice and The Immortal Hulk Neal Curtis The University of Auckland, New Zealand Abstract This article uses Kafka's short story 'Before the Law' to offer a reading of Al Ewing's The Immortal Hulk. This is in turn used to explore our desire to encounter the Law understood as a form of completeness. The article differentiates between 'the Law' as completeness or limitlessness and 'the law' understood as limitation. The article also examines this desire to experience completeness or limitlessness in the work of George Bataille who argued such an experience was the path to sovereignty. In response it also considers Francois Flahault's critique of Bataille who argued Bataille failed to understand limitlessness is split between a 'good infinite' and a 'bad infinite', and that it is only the latter that can ultimately satisfy us. The article then proposes The Hulk, especially as presented in Al Ewing's The Immortal Hulk, is a study in where our desire for limitlessness can take us. Ultimately it proposes we turn ourselves away from the Law and towards the law that preserves and protects our incompleteness. Keywords: Law; sovereignty; comics; superheroes; The Hulk Introduction From Jean Bodin to Carl Schmitt, the foundation of the law, or what we more readily understand as sovereignty, is marked by a significant division. The law is a limit in the sense of determining what is permitted and what is proscribed, but the authority for this limit is often said to derive from something unlimited. -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Winter in Westchester Weekend Offers Special Treats

Vol. LIII No. 4 Dec. 2011 Winter In Westchester Weekend Offers Special Treats Enjoy the prospect of playing with a pro, sipping wine and hav- Saturday there will be a two session pairs game at the Bridge ing dinner for only $15? Like playing in pairs events for extra Deck. Play either one or both sessions. Additional masterpoints masterpoints? Perhaps you want to live like a Vanderbilt for a will be awarded to the two session winners. Game times are day? Then join us for the Winter in Westchester weekend January 10:00 AM and 3:00 PM. 6th-8th. Special events include a Friday Pro Am, Saturday special pairs game and Sunday Swiss Teams event at Sleepy Hollow Join us on Sunday for stratified Swiss Teams at sumptuous Country Club. Sleepy Hollow Country Club. Play bridge where the Vanderbilts, Astors and Rockefellers did. You won’t be able to enjoy the The weekend kicks off with a Unit Pairs Championship game at Tillinghast designed golf course, but you can admire the grand the Bridge Deck at 1 PM. Festivities continue in the evening at ballroom, stained glass windows, and amazing Hudson River the Bridge Deck with a Pro Am. For only $15, players with less views from the 338 acres of hills and woodlands. The entry fee of than 100 masterpoints will be paired with experienced local play- $40 per person includes continental breakfast, lunch and a full ers, and enjoy dinner, wine and post game hand analyses. Ams day of bridge. The club is located at 777 Albany Post Road in will be assigned to a life master or better, with some Ams ran- Scarborough, just a few minutes past Tarrytown, and convenient domly paired with local bridge professionals. -

Q33384 William Blake and Speculative Fiction Assignment 2

Commentary on the Adaptation of Blake’s America: A Prophecy into a Series of Murals Inspired by Northern Irish Political Art and Popular Art Within the Graphic Novels of Alan Moore and Bryan Talbot. Joel Power 1 Overview Blake’s America: A Prophecy is a response to great social and political upheaval present at the end of the eighteenth century, and what Bindman calls a ‘revolutionary energy’2 in America and France. My mural adaptations focus on plates 8-10, a dialogue between this ‘revolutionary energy’, personified by 1 My images as they would appear in situ. 2 David Bindman, in William Blake, America a Prophecy, in The Complete Illuminated Books, ed. by David Bindman (London: Thames and Hudson, 2001), p. 153. INNERVATE Leading student work in English studies, Volume 8 (2015-2016), pp. 233-241 Joel Power 234 Orc, and Urizen in the guise of Albion’s Angel, before the poem turns into Blake’s ‘mythical version’3 of the American War of Independence. The genre of murals, as with those in Northern Ireland, create narratives ‘rich in evocative imagery’ presenting ‘aspirations, hopes, fears and terror’,4 telling of stories and legends between the past, present and future. The rebellious nature of the medium makes it an apt vehicle through which to adapt Blake’s work. Enriched with graphic imagery and intertextuality from Moore’s Promethea, Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Swamp Thing and Talbot’s The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, the three murals form part of a larger scale urban project which would reveal itself on city walls over a period of time, creating drama and intrigue. -

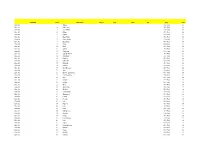

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto

Set Name Card Description Sketch Auto Mem #'d Odds Point Base Set 1 Angela 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 2 Anti-Venom 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 3 Doc Samson 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 4 Attuma 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 5 Bedlam 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 6 Black Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 7 Black Panther 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 8 Black Swan 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 9 Blade 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 10 Blink 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 11 Callisto 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 12 Cannonball 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 13 Captain Universe 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 14 Challenger 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 15 Punisher 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 16 Dark Beast 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 17 Darkhawk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 18 Collector 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 19 Devil Dinosaur 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 20 Ares 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 21 Ego The Living Planet 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 22 Elsa Bloodstone 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 23 Eros 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 24 Fantomex 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 25 Firestar 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 26 Ghost 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 27 Ghost Rider 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 28 Gladiator 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 29 Goblin Knight 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 30 Grandmaster 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 31 Hazmat 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 32 Hercules 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 33 Hulk 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 34 Hyperion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 35 Ikari 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 36 Ikaris 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 37 In-Betweener 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 38 Khonshu 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 39 Korvus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 40 Lady Bullseye 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 41 Lash 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 42 Legion 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 43 Living Lightning 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 44 Maestro 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 45 Magus 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 46 Malekith 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 47 Manifold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 48 Master Mold 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 49 Metalhead 4 Per Pack 24 Base Set 50 M.O.D.O.K. -

Superhuman, Transhuman, Post/Human: Mapping the Production and Reception of the Posthuman Body

Superhuman, Transhuman, Post/Human: Mapping the Production and Reception of the Posthuman Body Scott Jeffery Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Applied Social Science, University of Stirling, Scotland, UK September 2013 Declaration I declare that none of the work contained within this thesis has been submitted for any other degree at any other university. The contents found within this thesis have been composed by the candidate Scott Jeffery. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you, first of all, to my supervisors Dr Ian McIntosh and Dr Sharon Wright for their support and patience. To my brother, for allowing to me to turn several of his kitchens into offices. And to R and R. For everything. ABSTRACT The figure of the cyborg, or more latterly, the posthuman body has been an increasingly familiar presence in a number of academic disciplines. The majority of such studies have focused on popular culture, particularly the depiction of the posthuman in science-fiction, fantasy and horror. To date however, few studies have focused on the posthuman and the comic book superhero, despite their evident corporeality, and none have questioned comics’ readers about their responses to the posthuman body. This thesis presents a cultural history of the posthuman body in superhero comics along with the findings from twenty-five, two-hour interviews with readers. By way of literature reviews this thesis first provides a new typography of the posthuman, presenting it not as a stable bounded subject but as what Deleuze and Guattari (1987) describe as a ‘rhizome’. Within the rhizome of the posthuman body are several discursive plateaus that this thesis names Superhumanism (the representation of posthuman bodies in popular culture), Post/Humanism (a critical-theoretical stance that questions the assumptions of Humanism) and Transhumanism (the philosophy and practice of human enhancement with technology).