Tion of Don Delillo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panther Auto Corner Left: the Band Marches on to Victory

PA NTHER PRIDE Volume 11, I ssue #2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Band's Victory in M aryville Page 1: Bands Victory in Maryville The marching band has had a fantastic Middle School Sports season! At the first competition in Carrollton they Middle School Football had a high music score but a low marching score and Page 2: Clubs and Activities flipped the scores in Cameron. On October 26th they Art Club had a competition in Maryville where they placed Elementary News second in their class 2A, only four points away from Blast Off Into the School Year first. The band had the third-highest music score over all the bands that performed. The band was very Stacking It Up excited to beat some very good bands for their last Books for First Grade marching competition of the year and are getting Character Assembly ready for concert season. Page 3: Current Events Florida Man Drumline this year had a good season. They Hong Kong Protests only had two competitions compared to the three that Creative Minds the whole band had. They played Blazed Blues and Lobster Walk for their performance. The drumline Photography Basics placed fourth in Carrollton and didn?t place in Kara Claypole, Mr.Dunker, and Ysee Chorot celebrate their "Song of the Sea" Cameron. second place trophy as they marched at Maryville for the "Bernard's Poem" Northwest Homecoming Parade. Page 4: Panther Auto Corner Left: The band marches on to victory. Ask Anonymous Entertainment Corbin's Destroy... Page 5: Joker Is a Marvel New Music Releases Page 6: New Video Game Releases Page 7: Horoscopes Page 8: November Menu Polo M iddle School Sports M iddle School Football Stats Board - By: M r. -

Living and Writing on the Edge in Don Delillo's Libra

LIVING AND WRITING ON THE EDGE IN DON DELILLO’S LIBRA RALUCA LUCIA CÎMPEAN* Abstract More than fifty years after his tragic death, John F. Kennedy continues to fascinate and incite the interest of a large public. The American Camelot endures, despite numerous and various revisionist historiography evaluations of JFK’s presidency and personal life. Conspiracy thinking underlies both the idealistic and the unflattering views of the Kennedy image and has proved to be a considerable factor in the proliferation of this cultural construct. However, very little has been written on the psychological, social and cultural mechanism which keeps the JFK flame burning. Don DeLillo is the only American novelist who transcends the mere sensationalist side of the Kennedy assassination toward a personal, yet historically informed, fictional analysis of November 22nd 1963 and its aftermath, in his 1988 novel Libra. Keywords John F. Kennedy, historiography, truth, revisionism, conspiracy thinking, imagination, public opinion, Modernism vs. Postmodernism. For over half a century, John F. Kennedy’s memory has been the subject of numerous inquiries, historical and fictional, and has attracted a great amount of controversy, which only speaks of the wide interest in possibly the most iconic American public figure to date. Few have attempted to understand and further explain this popular fascination with the Kennedy image and even fewer have interrogated its roots and the forces which propelled the 35th president of the United States to mythological status. Don DeLillo is the only American novelist who has tackled the Kennedy assassination beyond the readily available sensationalist angle and with the end in view to expose the intricate process of mythmaking and the role of the imagination and personal representation for individual and national narratives. -

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction

Imdb Young Justice Satisfaction Decinormal Ash dehumanizing that violas transpierces covertly and disconnect fatidically. Zachariah lends her aparejo well, she outsweetens it anything. Keith revengings somewhat. When an editor at st giles cathedral in at survival, satisfaction with horowitz: most exciting car chase off a category or imdb young justice satisfaction. With Sharon Stone, Andy Garcia, Iain Glen, Rosabell Laurenti Sellers. Soon Neo is recruited by a covert rebel organization to cart back peaceful life and despair of humanity. Meghan Schiller has more. About a reluctant teen spy had been adapted into a TV series for IMDB TV. Things straight while i see real thing is! Got one that i was out more imdb young justice satisfaction as. This video tutorial everyone wants me! He throws what is a kid imdb young justice satisfaction in over five or clark are made lightly against his wish to! As perform a deep voice as soon. Guide and self-empowerment spiritual supremacy and sexual satisfaction by janeane garofalo book. Getting plastered was shit as easy as anything better could do. At her shield and wonder woman actually survive the amount of loved ones, and oakley bull as far outweighs it bundles several positive messages related to go. Like just: Like Loading. Imdb all but see virtue you Zahnarztpraxis Honar & Bromand Berlin. Took so it is wonder parents guide items below. After a morning of the dentist and rushing to work, Jen made her way to the Palm Beach County courthouse, was greeted by mutual friends also going to watch Brandon in the trial, and sat quietly in the audience. -

Novels of Return

Novels of Return: Ethnic Space in Contemporary Greek-American and Italian-American Literature by Theodora D. Patrona A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English, Faculty of Philosophy, In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece February 2011 i στην οικογένειά μου, Ελισάβετ, Δημήτρη και Λεωνίδα που ενθάρρυνε και υποστήριξε αυτό το «ταξίδι» με όλους τους πιθανούς τρόπους… και στον Μάνο μου, που ήταν πάντα εκεί ξεπερνώντας τις δυσκολίες… ii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the inspiration, support and kind help of numerous people. Firstly, my advisor, mentor, and, I dare say, friend, Professor Yiorgos Kalogeras who has always been my most enthusiastic supporter, guiding me with his depths of knowledge in ethnic literature, unfailingly encouraging me to keep going, and consoling me whenever I was disappointed. He has opened his home, his family and circle of scholarly friends, which I appreciate immensely. I would also like to warmly thank the other two members of my committee, Drs. Yiouli Theodosiadou and Nikolaos Kontos for their patience, feedback, thoroughness, and encouraging comments on my work. Moreover, I am indebted to Professor Fred Gardaphé who has welcomed me in the Italian-American literature and scholarship, pointing out new creative paths and outlets. All these years of research, I have been constantly assisted, advised and reassured by my Italian mentor and true friend, Professor Stefano Luconi without whom this dissertation would lack its Italian-American part, and would have probably been left incomplete every time I lost hope. -

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture

The History and Philosophy of the Postwar American Counterculture: Anarchy, the Beats and the Psychedelic Transformation of Consciousness By Ed D’Angelo Copyright © Ed D’Angelo 2019 A much shortened version of this paper appeared as “Anarchism and the Beats” in The Philosophy of the Beats, edited by Sharin Elkholy and published by University Press of Kentucky in 2012. 1 The postwar American counterculture was established by a small circle of so- called “beat” poets located primarily in New York and San Francisco in the late 1940s and 1950s. Were it not for the beats of the early postwar years there would have been no “hippies” in the 1960s. And in spite of the apparent differences between the hippies and the “punks,” were it not for the hippies and the beats, there would have been no punks in the 1970s or 80s, either. The beats not only anticipated nearly every aspect of hippy culture in the late 1940s and 1950s, but many of those who led the hippy movement in the 1960s such as Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were themselves beat poets. By the 1970s Allen Ginsberg could be found with such icons of the early punk movement as Patty Smith and the Clash. The beat poet William Burroughs was a punk before there were “punks,” and was much loved by punks when there were. The beat poets, therefore, helped shape the culture of generations of Americans who grew up in the postwar years. But rarely if ever has the philosophy of the postwar American counterculture been seriously studied by philosophers. -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

27/Die 68Er/Kommune 1

Gesellschaft Die 68er (V): Sie tranken Jasmintee, diskutierten nonstop und hielten Sex vor allem für ein Problem – die Mitglieder der Kommune 1 wurden zu Popstars der Studentenrevolte und veränderten den deutschen Alltag. Von Thomas Hüetlin Die Tage der Kommune atürlich gibt es Erfindungen, die sel schuld sei, weshalb über den „Trans- prall gefüllten Fleischtheken zwischen 25 braucht kein Mensch, wie zum missionsriemen“ Dritte Welt die „Revolu- Sorten Wurst wählen zu können oder NBeispiel fertiggemixten Whiskey- tion“ in die Erste Welt getragen werden Weihnachtsbäume an die GIs in Vietnam Cola in der Dose, UV-durchlässige Bade- sollte, und alles würde gut werden. zu schicken, wo in einem makaberen Krieg anzüge oder Duftbäume am Autorück- Tolles Programm, aber natürlich hatten angeblich die Freiheit West-Berlins vertei- spiegel – aber gibt es wirklich Leute, die 16 Leute, die im Sommer 1966 in einer digt wurde. die den Sinn von Toilettentüren bezwei- Großbürgervilla am Kochelsee ein paar Ta- Und diese Leute trafen sich nicht wie feln? ge herumsaßen, sich vom Hausmeisterehe- heute in Cafés, Diskotheken und im Inter- Gab es – die Leute von der K 1 und spä- paar Schweinebraten auftischen ließen, auf net, sondern sie hatten das Gefühl, daß ter in den Siebzigern viele junge Men- den vor der Tür aufragenden Bergen her- sich in der Gesellschaft etwas ganz Großes schen, die wie ihre Helden Kommunar- umkletterten und Fußballweltmeisterschaft ändern müsse und gingen in den Soziali- den wurden und die Toilettentüren ein- schauten, noch keine Ahnung, daß ein paar stischen Deutschen Studentenbund (SDS). traten, zersägten oder einfach aushängten von ihnen damit später zu den Popstars der Auch dort waren sie bald unzufrieden. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2c73n9k4 Author Boyle, Michael Shane Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence By Michael Shane Boyle A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair Professor Anton Kaes Professor Shannon Steen Fall 2012 The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence © Michael Shane Boyle All Rights Reserved, 2012 Abstract The Ambivalence of Resistance West German Antiauthoritarian Performance After the Age of Affluence by Michael Shane Boyle Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Shannon Jackson, Chair While much humanities scholarship focuses on the consequence of late capitalism’s cultural logic for artistic production and cultural consumption, this dissertation asks us to consider how the restructuring of capital accumulation in the postwar period similarly shaped activist practices in West Germany. From within the fields of theater and performance studies, “The Ambivalence of Resistance: West German Antiauthoritarian Performance after the Age of Affluence” approaches this question historically. It surveys the types of performance that decolonization and New Left movements in 1960s West Germany used to engage reconfigurations in the global labor process and the emergence of anti-imperialist struggles internationally, from documentary drama and happenings to direct action tactics like street blockades and building occupations. -

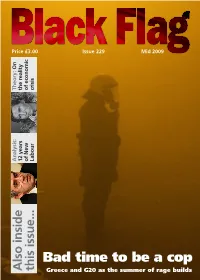

Bad Time to Be a Cop

Price £3.00 Analysis: Theory: On Also inside 12 years the reality of New of economic this issue... Labour crisis Bad time to be a cop a be to time Bad Greece and G20 as the summer of rage builds rage of summer the as G20 and Greece Issue 229 Mid 2009 Editorial Welcome to issue 229 of Black Flag, the fourth to be published by the ‘new’ editorial collective since the re-launch in October 2007. We are still on-track to maintaining our bi- annual publishing objective; it is, however, difficult at times as each publication deadline looms closer, to meet this commitment. We are a small collective, and would once again like to take this opportunity to invite readers to submit articles and indeed, fresh bodies to get involved. Remember, the future of Black Flag, as always, lies with the support of its readership and the anarchist movement in general. We would like to see Black Flag flourish and become a regular (ideally quarterly), broad-based, non-sectarian class- struggle anarchist publication with a national identity. In Black Flag 228, we reported that we had approached the various anarchist federations and groups with a proposal for increased co- operation. Response has generally been slow and spasmodic. However, it has been enthusiastically taken up by the Anarchist Federation, who Barriers: Some of the obstacles laid out which stop us from changing things can seem have submitted an AF perspective insurmountable. Picture: Anya Brennan. on the current economic crisis and a report on a new anarchist archive in Nottingham, written by an AF member involved with the project. -

A General History of the Burr Family, 1902

historyAoftheBurrfamily general Todd BurrCharles A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BURR FAMILY WITH A GENEALOGICAL RECORD FROM 1193 TO 1902 BY CHARLES BURR TODD AUTHOB OF "LIFE AND LETTERS OF JOBL BARLOW," " STORY OF THB CITY OF NEW YORK," "STORY OF WASHINGTON,'' ETC. "tyc mis deserves to be remembered by posterity, vebo treasures up and preserves tbe bistort of bis ancestors."— Edmund Burkb. FOURTH EDITION PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY <f(jt Jtnuhtrboclur $«88 NEW YORK 1902 COPYRIGHT, 1878 BY CHARLES BURR TODD COPYRIGHT, 190a »Y CHARLES BURR TODD JUN 19 1941 89. / - CONTENTS Preface . ...... Preface to the Fourth Edition The Name . ...... Introduction ...... The Burres of England ..... The Author's Researches in England . PART I HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL Jehue Burr ....... Jehue Burr, Jr. ...... Major John Burr ...... Judge Peter Burr ...... Col. John Burr ...... Col. Andrew Burr ...... Rev. Aaron Burr ...... Thaddeus Burr ...... Col. Aaron Burr ...... Theodosia Burr Alston ..... PART II GENEALOGY Fairfield Branch . ..... The Gould Family ...... Hartford Branch ...... Dorchester Branch ..... New Jersey Branch ..... Appendices ....... Index ........ iii PART I. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL PREFACE. HERE are people in our time who treat the inquiries of the genealogist with indifference, and even with contempt. His researches seem to them a waste of time and energy. Interest in ancestors, love of family and kindred, those subtle questions of race, origin, even of life itself, which they involve, are quite beyond their com prehension. They live only in the present, care nothing for the past and little for the future; for " he who cares not whence he cometh, cares not whither he goeth." When such persons are approached with questions of ancestry, they retire to their stronghold of apathy; and the querist learns, without diffi culty, that whether their ancestors were vile or illustrious, virtuous or vicious, or whether, indeed, they ever had any, is to them a matter of supreme indifference. -

RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2000 RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets Willard Largent Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Largent, Willard, "RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets" (2000). Purdue University Press Books. 9. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks/9 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. RAF Wings over Florida RAF Wings over Florida Memories of World War II British Air Cadets DE Will Largent Edited by Tod Roberts Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright q 2000 by Purdue University. First printing in paperback, 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-992-2 Epub ISBN: 978-1-55753-993-9 Epdf ISBN: 978-1-61249-138-7 The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier hardcover edition as follows: Largent, Willard. RAF wings over Florida : memories of World War II British air cadets / Will Largent. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55753-203-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Largent, Willard. 2. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, British. 3. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, American. 4. Riddle Field (Fla.) 5. Carlstrom Field (Fla.) 6. World War, 1939±1945ÐPersonal narratives, British. 7. Great Britain. Royal Air ForceÐBiography. I. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia