Der Blick Auf Die DDR Und Ihre Musikwissenschaft „Von Außen“

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

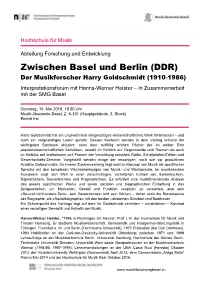

2018 05 15 Interpretationsforum

Hochschule für Musik Abteilung Forschung und Entwicklung Zwischen Basel und Berlin (DDR) Der Musikforscher Harry Goldschmidt (1910-1986) Interpretationsforum mit Hanns-Werner Heister – in Zusammenarbeit mit der SMG Basel Dienstag, 15. Mai 2018, 19.00 Uhr Musik-Akademie Basel, Z. 6-301 (Hauptgebäude, 3. Stock) Eintritt frei Harry Goldschmidt hat ein ungewöhnlich vielgestaltiges wissenschaftliches Werk hinterlassen – und auch ein vielgestaltiges Leben gehabt. Dessen Konturen werden in dem Vortrag anhand der wichtigsten Stationen skizziert, samt dem auffällig reichen Fächer der im weiten Sinn populärwissenschaftlichen Aktivitäten, sowohl im Hinblick auf Gegenstände und Themen als auch im Hinblick auf Institutionen und Formen der Vermittlung zwischen Radio, Schallplatten-Edition und Gewerkschafts-Seminar. Vorgestellt werden einige der neuartigen, nach wie vor produktiven Ansätze Goldschmidts. Ihr innerer Zusammenhang liegt wohl im Konzept von Musik als spezifischer Sprache mit den komplexen Wechselwirkungen von Musik- und Wortsprache. Im musikalischen Kunstwerk zeigt sich Welt in einer vielschichtigen, vermittelten Einheit von Syntaktischem, Sigmatischem, Semantischem und Pragmatischem. Es erfordert eine multidimensionale Analyse des jeweils spezifischen Werks und seiner sozialen und biographischen Einbettung in das Zeitgeschehen, um Motivation, Gestalt und Funktion «explizit» zu verstehen, also sein «So-und-nicht-anders-Sein», sein Gewordensein und sein Wirken – daher auch die Renaissance der Biographie, als «Sozialbiographie» mit den beiden -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Communist Nationalisms, Internationalisms, and Cosmopolitanisms

Edinburgh Research Explorer Communist nationalisms, internationalisms, and cosmopolitanisms Citation for published version: Kelly, E 2018, Communist nationalisms, internationalisms, and cosmopolitanisms: The case of the German Democratic Republic. in E Kelly, M Mantere & DB Scott (eds), Confronting the National in the Musical Past. 1st edn, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315268279 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.4324/9781315268279 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Confronting the National in the Musical Past General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Preprint. Published in Confronting the National in the Musical Past, ed. Elaine Kelly, Markus Mantere, and Derek B. Scott (London & New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 78- 90. Chapter 5 Communist Nationalisms, Internationalisms, and Cosmopolitanisms: The Case of the German Democratic Republic Elaine Kelly One of the difficulties associated with attempts to challenge the hegemony of the nation in music historiography is the extent to which constructs of nation, national identity, and national politics have actually shaped the production and reception of western art music. -

Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Comparative Analysis of Recorded Performances, Pp

BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Mark Christopher Ferraguto August 2012 © 2012 Mark Christopher Ferraguto BEETHOVEN’S FOURTH SYMPHONY: RECEPTION, AESTHETICS, PERFORMANCE HISTORY Mark Christopher Ferraguto, PhD Cornell University 2012 Despite its established place in the orchestral repertory, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-flat, op. 60, has long challenged critics. Lacking titles and other extramusical signifiers, it posed a problem for nineteenth-century critics espousing programmatic modes of analysis; more recently, its aesthetic has been viewed as incongruent with that of the “heroic style,” the paradigm most strongly associated with Beethoven’s voice as a composer. Applying various methodologies, this study argues for a more complex view of the symphony’s aesthetic and cultural significance. Chapter I surveys the reception of the Fourth from its premiere to the present day, arguing that the symphony’s modern reputation emerged as a result of later nineteenth-century readings and misreadings. While the Fourth had a profound impact on Schumann, Berlioz, and Mendelssohn, it elicited more conflicted responses—including aporia and disavowal—from critics ranging from A. B. Marx to J. W. N. Sullivan and beyond. Recent scholarship on previously neglected works and genres has opened up new perspectives on Beethoven’s music, allowing for a fresh appreciation of the Fourth. Haydn’s legacy in 1805–6 provides the background for Chapter II, a study of Beethoven’s engagement with the Haydn–Mozart tradition. -

Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Michael James Schmidt 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany Committee: David F. Crew, Supervisor Judith Coffin Sabine Hake Tracie Matysik Karl H. Miller The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany by Michael James Schmidt, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 To my family: Mom, Dad, Paul, and Lindsey Acknowledgements I would like to thank, above all, my advisor David Crew for his intellectual guidance, his encouragement, and his personal support throughout the long, rewarding process that culminated in this dissertation. It has been an immense privilege to study under David and his thoughtful, open, and rigorous approach has fundamentally shaped the way I think about history. I would also like to Judith Coffin, who has been patiently mentored me since I was a hapless undergraduate. Judy’s ideas and suggestions have constantly opened up new ways of thinking for me and her elegance as a writer will be something to which I will always aspire. I would like to express my appreciation to Karl Hagstrom Miller, who has poignantly altered the way I listen to and encounter music since the first time he shared the recordings of Ellington’s Blanton-Webster band with me when I was 20 years old. -

Full Dissertation All the Bits 150515 No Interviews No

The Practice and Politics of Children’s Music Education in the German Democratic Republic, 1949-1976 By Anicia Chung Timberlake A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Nicholas Mathew Professor Martin Jay Spring 2015 Abstract The Practice and Politics of Children’s Music Education in the German Democratic Republic, 1949-1976 by Anicia Chung Timberlake Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This dissertation examines the politics of children’s music education in the first decades of the German Democratic Republic. The East German state famously attempted to co-opt music education for propagandistic purposes by mandating songs with patriotic texts. However, as I show, most pedagogues believed that these songs were worthless as political education: children, they argued, learned not through the logic of texts, but through the immediacy of their bodies and their emotions. These educators believed music to be an especially effective site for children’s political education, as music played to children’s strongest suit: their unconscious minds and their emotions. Many pedagogues, composers, and musicologists thus adapted Weimar-era methods that used mostly non-texted music to instill what they held to be socialist values of collectivism, diligence, open-mindedness, and critical thought. I trace the fates of four of these pedagogical practices—solfège, the Orff Schulwerk, lessons in listening, and newly-composed “Brechtian” children’s operas—demonstrating how educators sought to graft the new demands of the socialist society onto inherited German musical and pedagogical traditions. -

Musikgeschichte in Mittel- Und Osteuropa

Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa Mitteilungen der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft an der Universität Leipzig Heft 16 in Zusammenarbeit mit den Mitgliedern der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa an der Universität Leipzig herausgegeben von Helmut Loos und Eberhard Möller † Redaktion: Klaus-Peter Koch Gudrun Schröder Verlag Leipzig 2015 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Für die erteilten Abbildungsgenehmigungen wird ausdrücklich gedankt. Autoren und Verlag haben sich bemüht, sämtliche Rechteinhaber der Bilder ausfindig zu machen. Sollte dies an einer Stelle nicht gelungen sein, bitten die Herausgeber um Mitteilung. Berechtigte Ansprüche werden selbstverständlich im Rahmen der üblichen Vereinbarungen abgegolten. © 2015 Gudrun Schröder Verlag, Leipzig Kooperation: Rhytmos, ul. Grochmalickiego 35/1, 61-606 Poznań, Polen Satz: Linus Hartmann Printed in Poland. ISBN 978-3-926196-72-9 Inhalt Vorwort . vi Ol’ga Bentsch Einige Beiträge zur Geschichte der ukrainischen Musikfolklore . 1 Julian Heigel Überlegungen zur musikhistorischen Aufarbeitung der DDR-Ära am Beispiel des Deutschen Verlags für Musik ............... 8 Jakym Horak und Severyn Tykhyy Die Musikbibliothek von Volodymyr Sadovs’kyj . 18 Ulyana Hrab Myroslav Antonovyč und seine wissenschaftliche Biografie . 87 Maria Kachmar Musical Structure of Byzantine Monodic Church Chants: from Sign to Principle . 96 Klaus-Peter Koch Die böhmischen Mozart-Enthusiasten in Franz Xaver Niemetscheks Mozart-Biografie von 1798 . 107 Helmut Loos „. dass in unserm Breslau wahrlich nicht die Armut an ernst stre- benden Musikmenschen herrscht“. Berichte über das Breslauer Musikleben in der Leipziger Musikzeit- schrift Signale für die musikalische Welt . -

Introduction

XXV Introduction Piano music plays a peculiar role in Eisler’s thought and work. full his art of constructing motivic and thematic relationships It was bound up with his beginnings as a composer and he and his ability to create contrapuntal combinations.3 This returned to it when he had the leisure to compose. But at the Sonata is essentially in the atonal idiom of the Second Vien same time it acted as a kind of negative foil to his “real” activ nese School, but its tonal residue (such as in the unresolved ities, namely his support for the workers’ movement and for a dominant seventh/ninth chord at the close of the main theme music that could be utilized in its struggle for a socialist society. in the first movement) reveals a trait that Reinhold Brinkmann Eisler’s piano music is to a certain extent that of the “private” sees as characteristic of the “future critical singer”: “If we don’t composer, and he made little fuss about it. The piano was his wish to dismiss its [i.e. the chord’s] isolation as a break in the instrument, and his playing is said to have possessed a great style, then it can hardly be understood as anything other than deal of charisma, despite his technical deficiencies.1 Eisler’s parodistic”.4 piano oeuvre is more extensive than that of his teacher Arnold The Second Sonata was composed shortly afterwards. Al Schoenberg. Besides occasional pieces, we also find works that though it was given the opus number “6”, it was neither per we can describe as being of major importance, either on ac formed nor published at the time. -

The Reception and Performance of Classical

Beethoven as “Paradigmatic Socialist Warrior”: The Reception and Performance of Classical Music in the GDR Word Count: 18,601 Daniel Shao April 17th, 2020 Seminar Advisor: Natasha Lightfoot Second Reader: Victoria Phillips 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements 2 Abbreviations 3 Images 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1. Interpreting the Canon: Musicology and Late Socialism 15 Chapter 2. Programming the Canon: Performance and Censorship 36 Chapter 3. Performing the Canon: The Case of Kurt Masur 51 Conclusion: 74 Bibliography: 77 2 Acknowledgements: I feel obliged to acknowledge all of my mentors and peers who have supported me through the entire thesis-writing process, who have all given me a great deal of support without asking for anything in return. Firstly, I would like to thank Professor Lightfoot for her helpful and detailed feedback over the course of the year, as well as her accomodation of my request to informally remain in her seminar despite some scheduling conflicts second semester. Of course, I would not have been able to do this project without the help of Professor Berghahn, who kindly came out of retirement to offer me suggestions for secondary source reading and archives to visit. Besides Professor Berghahn, I am also grateful to Professor Tooze, Mazower, and Kaye for their help, not only in helping me plan out this thesis, but also in giving me valuable advice for my graduate school applications this year. I would not be the aspiring historian I am today without their mentorship over the course of my undergraduate studies. I would also like to thank my second reader, Professor Victoria Phillips, for her detailed feedback, which she happily provided despite her extremely busy schedule this semester. -

Sozialistische Filmkunst Eine Dokumentation Sozialistische Filmkunst

Klaus-Detlef Haas, Dieter Wolf (Hrsg.) Sozialistische Filmkunst Eine Dokumentation Sozialistische Filmkunst 90 MS 90_KINO_D1 05.04.2011 9:45 Uhr Seite 1 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Manuskripte 90 MS 90_KINO_D1 05.04.2011 9:45 Uhr Seite 2 MS 90_KINO_D1 05.04.2011 9:45 Uhr Seite 3 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung KLAUS-DETLEF HAAS, DIETER WOLF (HRSG.) Sozialistische Filmkunst Eine Dokumentation Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin MS 90_KINO_D1 05.04.2011 9:45 Uhr Seite 4 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, Reihe: Manuskripte, 90 ISBN 978-3-320-02257-0 Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin GmbH 2011 Satz: Elke Jakubowski Druck und Verarbeitung: Mediaservice GmbH Druck und Kommunikation Printed in Germany MS 90_KINO_D1 05.04.2011 9:45 Uhr Seite 5 Inhalt Vorwort 11 2005 | Jahresprogramm 13 Günter Reisch: Erinnern an Konrad Wolf an seinem 80. Geburtstag 15 Mama, ich lebe Einführung | Programmzettel 17 Sterne Einführung | Programmzettel 22 Busch singt Teil 3. 1935 oder Das Faß der Pandora Teil 5. Ein Toter auf Urlaub Programmzettel 27 Solo Sunny Programmzettel 29 Der nackte Mann auf dem Sportplatz Programmzettel 30 Goya oder Der arge Weg der Erkenntnis Einführung | Programmzettel 32 Ich war neunzehn Programmzettel 38 Professor Mamlock Programmzettel 40 Der geteilte Himmel Einführung | Programmzettel 42 Addio, piccola mio Programmzettel 47 Leute mit Flügeln Programmzettel 49 MS 90_KINO_D1 05.04.2011 9:45 Uhr Seite 6 2006 | Jahresprogramm 51 Sonnensucher Programmzettel 53 Lissy Programmzettel 55 Genesung Programmzettel 57 Einmal ist keinmal Programmzettel 59 Die Zeit die bleibt Programmzettel -

The Political Songs of Hanns Eisler, 1926-1932 Margaret R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Workers, Unite!: The Political Songs of Hanns Eisler, 1926-1932 Margaret R. Jackson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC WORKERS, UNITE! THE POLITICAL SONGS OF HANNS EISLER, 1926-1932 By MARGARET R. JACKSON A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Margaret R. Jackson defended on November 10, 2003. ______________________ Jerrold Pope Professor Directing Treatise ______________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _______________________ Stanford Olsen Committee Member _______________________ Marcia Porter Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………iv Terms and Abbreviations……………………………………………………………v Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………..vi INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………….1 1. An Overview of the Life of Hanns Eisler ………………………………………4 2. Hanns Eisler and Dialectical Materialism………………………………………11 3. Music-making in the Agitprop Realm…………………………………………..22 4. Hanns Eisler’s Fighting Songs, 1926-1932……………………………………..34 5. Eisler’s Fate in U.S. Musicology………………………………………………..54 CONCLUSION……………………………………………………….…………….67 REFERENCES…………………………………………………….……………….70 -

Hanns Eisler and the FBI,” in Modernism on File: Writers, Artists, and the FBI, 1920–1950 , Ed

Hans Eisler and the FBI JAMES WIERZBICKI To judge from the waves of scholarship and performances that marked the 1998 centennial of his birth, the composer Hanns Eisler has already attained the status of national hero in his native Germany. But in the United States, where he lived from 1937 until 1948, Eisler remains by and large a shadowy figure. 1 Musicological treatment of Eisler in the United States—indeed, in the west in general—amounts to a brush-off. When serious interest in Eisler has been expressed, typically it has centered on the handful of scores he wrote for Hollywood films and a theoretical book about film music that he co- authored with Theodor Adorno. 2 Beyond that, the standard “read” on Eisler is that he was once upon a time an adventurous musical modernist but then consigned himself to the sidelines when, in the mid-1920s, he espoused the idea that music is useless if it is directed only toward sophisticated ears. As rapidly as Eisler’s music gained in aural simplicity, it seems, so it lost status in the minds of western critics. More than a quarter-century ago British composer-musicologist David Blake, one of Eisler’s few non-German champions, concluded his Grove Dictionary article on Eisler with what amounts to an exhortation: “No composer has suffered more from the post-1945 cultural cold war. As the cross-currents between Eastern Europe and the west increase, a proper international A shorter version of this article appeared as “Sour Notes: Hanns Eisler and the FBI,” in Modernism on File: Writers, Artists, and the FBI, 1920–1950 , ed.