The Party Politics of Legislative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Germany's Foreign Policy: France Wears the Breaches?!

Date submitted: 24-06-2016 Master Thesis GERMANY’S FOREIGN POLICY: FRANCE WEARS THE BREACHES?! Supervisor: Dr. G.C. van der Kamp- Alons Second Reader: Dr. T. Eimer Author: Anne Brockherde S4396774 University: Radboud University Nijmegen Study: Political Science (MSc) Specialisation: International Relations PREFACE The process to the final version of this thesis was one with a lot of obstacles - like every student who finished his master studies with the creation of the thesis will probably claim. The process in thinking, in understanding, in being capable to see the events around us in a different context and from several perspectives, is one, which needs a lot of effort. Adaptation of the way of thinking is one of the most difficult adaptations the mind needs to go through. Next to the development concerning critical thinking and gaining the knowledge which is necessary to follow and participate in the highly valuable discussions of the lessons, private developments arise. Not only the question, where I would like to go after my studies, but first of all the question, what specific goals I have in life, kept my mind busy. These factors and also external influences on the process of writing my thesis made me consider an internship in the area of International Relations before finishing the thesis. The choice to do an internship at the Asser Institute in The Hague was one of the best of my young career. I got to know the most important international and national organisations, and it left me with not only a lot of knowledge and a big network, but also with friends. -

Berlin Foreign Policy Forum

Berlin Foreign Policy Forum Humboldt Carré 10–11 November 2014 Participants Ambassador Dr. Mustapha ADIB, Ambassador of Bastian BENRATH, Deutsche Journalistenschule, the Lebanese Republic, Berlin Munich Dr. Ebtesam AL-KETBI, President, Emirates Policy Andrea BERDESINSKI, Körber Network Foreign Center, Abu Dhabi Policy; Desk Officer, Policy Planning Staff, Ambassador Dr. Hussein Mahmood Fadhlalla Federal Foreign Office, Berlin ALKHATEEB, Ambassador of the Republic of Iraq, Bernt BERGER, Senior Research Fellow and Head, Berlin Asia Program, Institute for Security and Development Policy (ISDP), Stockholm Katrina ALLIKAS, Secretary-General, Latvian Transatlantic Organisation (LATO), Riga Deidre BERGER, Director, American Jewish Committee (AJC), Berlin Sultan AL QASSEMI, Columnist, Sharjah Dr. Joachim BERTELE, Head of Division, Bilateral Fawaz Meshal AL-SABAH, Munich Young Leader 2009; Director, Department for International Relations with the States of the Central, East Relations, National Security Bureau, Kuwait City and South-East Europe as well as Central Asia and the Southern Caucasus, Federal Ambassador Dr. Mazen AL-TAL, Ambassador of Chancellery, Berlin the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, Berlin Dr. Christoph BERTRAM, fmr. Director, German Niels ANNEN, MP, Member, Committee on Institute for International and Security Affairs Foreign Affairs, Deutscher Bundestag, Berlin (SWP), Hamburg Prof. Uzi ARAD, fmr. National Security Adviser to Ralf BESTE, Deputy Head, Policy Planning Staff, the Prime Minister, Herzliya Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Prof. Dr. Pavel BAEV, Research Director and Commodore (ret.) Chitrapu Uday BHASKAR, Research Professor, Peace Research Institute Director, Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi Oslo (PRIO) Brigadier General (ret.) Helmut BIALEK, Senior Dr. Thomas BAGGER, Head, Policy Planning Staff, Advisor, Military Liaison, Munich Security Federal Foreign Office, Berlin Conference Helga BARTH, Head of Division, Middle East, Prof. -

CDU/CSU): Vielen Dank, Liebe Kolleginnen Und Kollegen

TOP 1 Auswärtiges Amt 111. Sitzung, 11. September 2019 Roderich Kiesewetter (CDU/CSU): Vielen Dank, liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen. – Herr Präsident! Meine sehr geehrten Damen und Herren! Meinen Geburtstag habe ich seinerzeit 2001 tatsächlich in den USA verbracht und nicht so gute Erinnerungen daran. Danke, dass ich meinen Geburtstag heute in der Runde von Kolleginnen und Kollegen begehen darf. Viele von Ihnen haben heute die Besorgnis kundgetan, dass die internationale regelbasierte Ordnung unter Druck steht. Diese Besorgnis sollten wir wenden und es als unsere Aufgabe verstehen, als Aufgabe Deutschlands in Europa, als Aufgabe der Europäischen Union, uns sehr stark für den Erhalt und die Wiederherstellung der regelbasierten internationalen Ordnung einzusetzen – für Menschenrechte, Rechtsstaatlichkeit, freien Welthandel, aber auch für koordinierte Entwicklungszusammenarbeit –, und wir sollten unsere Kraft dafür einsetzen, dass die, die in den letzten Jahren davon abgewichen sind, auf den Pfad der regelbasierten Ordnung zurückgeführt werden. (Beifall bei der CDU/CSU und der SPD) Liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen, ich möchte das am Beispiel Russlands deutlich machen. Putin hat im Juli 2018 in London kurz vor dem G-20-Gipfel sehr deutlich gesagt, der Liberalismus sei abgenutzt. Lassen Sie uns das als Ermahnung begreifen. Aber er ist nicht abgenutzt; vielmehr müssen wir uns neu sortieren. Lassen Sie mich drei Herausforderungen ansprechen, mit denen uns Russland konfrontiert und über deren Umgang auch in diesem Hause keine Einigkeit erzielt werden kann. Die erste der drei Herausforderungen ist aus meiner Sicht der Mythos, dass Russland in einer Opferrolle sei, weil ost- und mitteleuropäische Staaten sich für NATO und EU entschieden haben. Dem sollten wir – und das ist die feste Auffassung der Union – gegenhalten. -

Antrag Der Abgeordneten Karl Lamers, Christian Schmidt (Fürth), Dr

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/3378 14. Wahlperiode 16. 05. 2000 Antrag der Abgeordneten Karl Lamers, Christian Schmidt (Fürth), Dr. Andreas Schockenhoff, Dr. Friedbert Pflüger, Hans-Dirk Bierling, Dr. Karl A. Lamers (Heidelberg) und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU Für eine gemeinsame europäische Position in der Frage der Raketenabwehr (National Missile Defense) Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Die Bedrohung durch Massenvernichtungswaffen ist weltweit gewachsen. Die Zahl der Staaten, die über atomare, chemische und biologische Sprengköpfe verfügen, steigt. Gleichzeitig konnten die Reichweiten dieser dort verfügbaren ballistischer Raketen deutlich gesteigert werden. Proliferationsberichte zeich- nen ein beunruhigendes Bild möglicher Gefahren. Diese Situation hat in den Vereinigten Staaten zur Initiative für eine nationale Raketenabwehr (National Missile Defense) geführt. Die USA stellen dabei die Schwierigkeiten in Rech- nung, bestimmte Regime über vertragliche Verifizierungsmaßnahmen von der Entwicklung und Weitergabe von Raketentechnologie abzuhalten. Europa kann sich der Frage eines Schutzschirmes gegen Raketen, die potenziell auch unser Territorium bedrohen, nicht entziehen. Die damit verbundene Diskussion ist von zentraler Bedeutung für die europäische und die globale Sicherheit sowie für den Zusammenhalt der Atlantischen Allianz. Sie betrifft die kooperativen Sicherheitsstrukturen und das bestehende Abrüstungs-, Rüs- tungskontroll- und Nichtverbreitungsvertragswerk. Insbesondere berührt sie den ABM-Vertrag -

Eyes Tight Shut: European Attitudes Towards Nuclear Deterrence

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN SCORECARD FLASH RELATIONS ecfr.eu EYES TIGHT SHUT: EUROPEAN ATTITUDES TOWARDS NUCLEAR DETERRENCE Manuel Lafont Rapnouil, Tara Varma & Nick Witney The 29 July edition of Germany’s Welt am Sonntag hit newsstands like a bombshell. The weapon in question was painted in German national colours, and illustrated the front- SUMMARY page headline “Do we need the bomb?” Inside, the writer • Europeans remain unwilling to renew their argued that: “For the first time since 1949, the Federal Republic thinking on nuclear deterrence, despite of Germany is no longer under the US nuclear umbrella.” growing strategic instability. Their stated goal of “strategic autonomy” will remain an empty It is extraordinary that this question should arise so phrase until they engage seriously on this matter. prominently in peace-loving, anti-nuclear Germany. But it is not before time. This year, the European Council on • This intellectual underinvestment looks set to Foreign Relations conducted a comprehensive survey continue despite: a revived “German bomb” of attitudes towards nuclear issues across the member debate; a new Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear states of the European Union. Two overarching themes Weapons; and the crumbling of the INF treaty. emerged. Firstly, despite the growing insecurity all around them, Europeans remain unwilling to face up to the • Attitudes to nuclear deterrence differ radically renewed relevance that nuclear deterrence ought to have from country to country – something which in their strategic thinking. Secondly, and as a consequence, any new engagement on the nuclear dimension national attitudes remain much where they were when will have to contend with. -

WHY EUROPE NEEDS a NEW GLOBAL STRATEGY Susi Dennison, Richard Gowan, Hans Kundnani, Mark Leonard and Nick Witney

BRIEF POLICY WHY EUROPE NEEDS A NEW GLOBAL STRATEGY Susi Dennison, Richard Gowan, Hans Kundnani, Mark Leonard and Nick Witney Today’s Europe is in crisis. But of all the world’s leading powers, SUMMARY It is now a decade since European leaders none has had so much success in shaping the world around approved the first-ever European Security it over the last 20 years as the European Union. The United Strategy (ESS), which began with the States provided the military underpinning for a Europe whole memorable statement that “Europe has and free, but its record in other parts of the world has been never been so prosperous, so secure nor mixed at best. Russia is still lagging behind where it was when so free”. But Europe and the world have the Cold War ended. Japan has stagnated. Meanwhile rising changed so dramatically in the last decade that it is increasingly hard to argue that powers such as China have not yet sought to reshape global the EU can simply stick to the “strategy” it politics in their image. But since the end of the Cold War, the agreed in 2003. Many of the approaches that EU has peacefully expanded to include 16 new member states worked so well for Europe in the immediate and has transformed much of its neighborhood by reducing aftermath of the Cold War seem to be ethnic conflicts, exporting the rule of law, and developing ineffectual at best and counter-productive economies from the Baltic to the Balkans. at worst in an age of power transition and global political awakening. -

Plenarprotokoll 19/106

Plenarprotokoll 19/106 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 106. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 26. Juni 2019 Inhalt: Präsident Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble ......... 12991 A Martin Erwin Renner (AfD) .............. 12996 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12997 A Ausschussüberweisung. 12991 D Martin Erwin Renner (AfD) .............. 12997 B Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12997 C Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Dr. Marco Buschmann (FDP) ............. 12997 C Befragung der Bundesregierung Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12991 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12997 D Dr. Gottfried Curio (AfD) ................ 12992 C Dr. Marco Buschmann (FDP) ............. 12997 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12992 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12998 A Dr. Gottfried Curio (AfD) ................ 12993 A Dr. Anja Weisgerber (CDU/CSU) .......... 12998 A Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12993 B Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12998 A Martin Schulz (SPD) .................... 12993 B Susann Rüthrich (SPD) .................. 12998 B Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12993 C Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12998 C Martin Schulz (SPD) .................... 12994 B Susanne Ferschl (DIE LINKE) ............ 12998 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12994 C Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12999 A Katja Suding (FDP). 12994 D Susanne Ferschl (DIE LINKE) ............ 12999 B Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin ....... 12994 D Dr. Angela Merkel, Bundeskanzlerin -

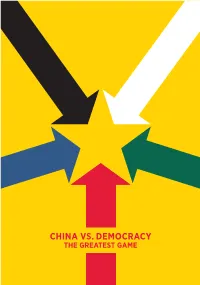

China Vs. Democracy the Greatest Game

CHINA VS. DEMOCRACY THE GREATEST GAME A HANDBOOK FOR DEMOCRACIES By Robin Shepherd, HFX Vice President ABOUT HFX HFX convenes the annual Halifax International Security Forum, the world’s preeminent gathering for leaders committed to strengthening strategic cooperation among democracies. The flagship meeting in Halifax, Nova Scotia brings together select leaders in politics, business, militaries, the media, and civil society. HFX published this handbook for democracies in November 2020 to advance its global mission. halifaxtheforum.org CHINA VS. DEMOCRACY: THE GREATEST GAME ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, HFX acknowledges Many experts from around the world the more than 250 experts it interviewed took the time to review drafts of this from around the world who helped to handbook. Steve Tsang, Director of the reappraise China and the challenge it China Institute at the School of Oriental poses to the world’s democracies. Their and African Studies (SOAS) in London, willingness to share their expertise and made several important suggestions varied opinions was invaluable. Of course, to early versions of chapters one and they bear no responsibility, individually or two. Peter Hefele, Head of Department collectively, for this handbook’s contents, Asia and Pacific, and David Merkle, Desk which are entirely the work of HFX. O!cer China, at Germany’s Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung made a number of This project began as a series of meetings very helpful suggestions. Ambassador hosted by Baroness Neville-Jones at the Hemant Singh, Director General of the U.K. House of Lords in London in 2019. Delhi Policy Group (DPG), and Brigadier At one of those meetings, Baroness Arun Sahgal (retired), DPG Senior Fellow Neville-Jones, who has been a stalwart for Strategic and Regional Security, friend and supporter since HFX began in provided vital perspective from India. -

Reframing Germany's Russia Policy

BRIEF POLICY REFRAMING GERMANY’S RUSSIA POLICY – AN OPPORTUNITY FOR THE EU Stefan Meister Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Germany has pursued SUMMARY Since Vladimir Putin’s return to the an integrative and co-operative Russia policy influenced by presidency in 2012, rifts have grown between the Ostpolitik of Chancellor Willy Brandt and his advisor Germany and Russia. Berlin has always Egon Bahr. Known in Germany as Neue Ostpolitik, “the New been an advocate for Russia in the European Eastern Policy”, this successful approach fostered dialogue Union, as the wish to help modernise Russia with the Soviet Union in the 1970s through political has dovetailed neatly with German economic recognition and economic co-operation.1 Following the interests. But the Putin regime is not interested Western integration pursued by the first Chancellor of the in modernisation or democracy. Putin’s Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer, Ostpolitik Russia seeks profit and power, including over was the second step towards developing a sovereign its post-Soviet neighbours such as Ukraine. As a result, Berlin has had to admit that its co- German foreign policy after the Second World War. The operative Russia policy has hit a wall. For the concept of “change through rapprochement” (Wandel first time in two decades, the German political durch Annäherung) played an important role in expanding elite is open to a more critical approach the scope of Germany’s foreign policy. By accepting political towards Russia and is searching for a new realities, Germany could create the conditions for the policy towards Eastern Europe, a policy that institution of platforms for communication and negotiations is co-operative without being deferential to with the Eastern Bloc. -

'Frostpolitik'? Merkel, Putin and German Foreign Policy Towards Russia

From Ostpolitik to ‘frostpolitik’? Merkel, Putin and German foreign policy towards Russia TUOMAS FORSBERG* Germany’s relationship with Russia is widely considered to be of fundamental importance to European security and the whole constitution of the West since the Second World War. Whereas some tend to judge Germany’s reliability as a partner to the United States—and its so-called Westbindung in general—against its dealings with Russia, others focus on Germany’s leadership of European foreign policy, while still others see the Russo-German relationship as an overall barometer of conflict and cooperation in Europe.1 How Germany chooses to approach Russia and how it deals with the crisis in Ukraine, in particular, are questions that lie at the crux of several possible visions for the future European order. Ostpolitik is a term that was coined to describe West Germany’s cooperative approach to the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries, initiated by Chan- cellor Willy Brandt in 1969. As formulated by Brandt’s political secretary, Egon Bahr, the key idea of the ‘new eastern policy’ was to achieve positive ‘change through rapprochement’ (Wandel durch Annäherung). In the Cold War context, the primary example of Ostpolitik was West Germany’s willingness to engage with the Soviet Union through energy cooperation including gas supply, but also pipeline and nuclear projects.2 Yet at the same time West Germany participated in the western sanctions regime concerning technology transfer to the Soviet Union and its allies, and accepted the deployment of American nuclear missiles on its soil as a response * This work was partly supported by the Academy of Finland Centre of Excellence for Choices of Russian Modernisation (grant number 250691). -

Kiesewetter Kompakt

Roderich Kiesewetter MdB Platz der Republik 11011 Berlin Telefon 030 227-77594 Telefax 030 227-76594 [email protected] Internet: www.roderich-kiesewetter.de Wahlkreisbüro: Wellandstraße 58 73434 Aalen Telefon 07361 5249 201 Telefax 07361 5249 202 [email protected] Kiesewetter kompakt 17/2011 – Persönliche Notizen – Was gut ist für Europa, ist auch gut für Deutschland Regierungserklärung von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel zum Europäischen Rat und zum Eurogipfel Deutschland seine Finanzierungszusagen für den Der Deutsche Bundestag hat sich an diesem Mitt- Rettungsschirm einlösen müsse. Nach Abwägung woch mit breiter Mehrheit für die Ausweitung der aller Argumente halte sie es aber für vertretbar, das Wirksamkeit des Rettungsschirms ausgesprochen, Risiko einzugehen: „Eine bessere Alternative liegt mit dem die Schuldenkrise im Euro-Raum gebannt mir nach Prüfung aller Argumente nicht vor. Es werden soll. Alle Fraktionen mit Ausnahme der wäre nicht vertretbar und nicht verantwortlich, das Linken stimmten dafür, dass die Europäische Sta- Risiko nicht einzugehen.“ Als weitere notwendige bilisierungsfazilität (EFSF), der sogenannte Euro- Maßnahmen zur Bewältigung der Schuldenkrise Rettungsschirm, mit Hilfe weiterer Instrumentarien im Euro-Raum nannte Merkel unter anderem die so effizient wie möglich genutzt werden kann. Einführung von Schuldenbremsen nach deutschem Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel hatte zuvor in Vorbild in den anderen Mitgliedstaaten, einer Kla- einer Regierungserklärung eindringlich an die Ab- gemöglichkeit gegen Stabilitätssünder vor dem geordneten appelliert, dafür auch vertretbare Risi- Europäischen Gerichtshof und einer Finanztransak- ken einzugehen. Sie wiederholte dabei ihr Credo: tionssteuer in der EU. Die Bundeskanzlerin warnte „Scheitert der Euro, scheitert Europa.“ Und das aber auch vor der Illusion, die Schuldenkrise in der dürfe nicht passieren, mahnte die Bundeskanzlerin.