Iconographic Anaylsis of Vase K1485 and Ancient Maya Skyscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panthéon Maya

Liste des divinités et des démons de la mythologie des mayas. Les noms sont tirés du Popol Vuh des Mayas Quichés, des livres de Chilam Balam et de Diego de Landa ainsi que des divers codex. Divinité Dieu Déesse Démon Monstre Animal Humain AB KIN XOC Dieu de poésie. ACAN Dieu des boissons fermentées et de l'ivresse. ACANTUN Quatre démons associés à une couleur et à un point cardinal. Ils sont présents lors du nouvel an maya et lors des cérémonies de sculpture des statues. ACAT Dieu des tatouages. AH CHICUM EK Autre nom de Xamen Ek. AH CHUY KAKA Dieu de la guerre connu sous le nom du "destructeur de feu". AH CUN CAN Dieu de la guerre connu comme le "charmeur de serpents". AH KINCHIL Dieu solaire (voir Kinich Ahau). AHAU CHAMAHEZ Un des deux dieux de la médecine. AHMAKIQ Dieu de l'agriculture qui enferma le vent quand il menaçait de détruire les récoltes. AH MUNCEN CAB Dieu du miel et des abeilles sans dard; il est patron des apiculteurs. AH MUN Dieu du maïs et de la végétation. AH PEKU Dieu du Tonnerre. AH PUCH ou AH CIMI ou AH CIZIN Dieu de la Mort qui régnait sur le Metnal, le neuvième niveau de l'inframonde. AH RAXA LAC DMieu de lYa Terre.THOLOGICA.FR AH RAXA TZEL Dieu du ciel AH TABAI Dieu de la Chasse. AH UUC TICAB Dieu de la Terre. 1 AHAU CHAMAHEZ Dieu de la Médecine et de la Guérison. AHAU KIN voir Kinich Ahau. AHOACATI Dieu de la Fertilité AHTOLTECAT Dieu des orfèvres. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

The Mayan Gods: an Explanation from the Structures of Thought

Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences Review Article Open Access The Mayan gods: an explanation from the structures of thought Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2018 This article explains the existence of the Classic and Post-classic Mayan gods through Laura Ibarra García the cognitive structure through which the Maya perceived and interpreted their world. Universidad de Guadalajara, Mexico This structure is none other than that built by every member of the human species during its early ontogenesis to interact with the outer world: the structure of action. Correspondence: Laura Ibarra García, Centro Universitario When this scheme is applied to the world’s interpretation, the phenomena in it and de Ciencias Sociales, Mexico, Tel 523336404456, the world as a whole appears as manifestations of a force that lies behind or within Email [email protected] all of them and which are perceived similarly to human subjects. This scheme, which finds application in the Mayan worldview, helps to understand the personality and Received: August 30, 2017 | Published: February 09, 2018 character of figures such as the solar god, the rain god, the sky god, the jaguar god and the gods of Venus. The application of the cognitive schema as driving logic also helps to understand the Maya established relationships between some animals, such as the jaguar and the rattlesnake and the highest deities. The study is part of the pioneering work that seeks to integrate the study of cognition development throughout history to the understanding of the historical and cultural manifestations of our country, especially of the Pre-Hispanic cultures. -

Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People

Mesoweb Publications POPOL VUH Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People Translation and Commentary by Allen J. Christenson 2007 Popol Vuh: Sacred Book of the Quiché Maya People. Electronic version of original 2003 publication. Mesoweb: www.mesoweb.com/publications/Christenson/PopolVuh.pdf. 1 To my wife, Janet Xa at nu saqil, at nu k'aslemal Chib'e q'ij saq ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This volume is the culmination of nearly twenty-five years of collaboration with friends and colleagues who have been more than generous with their time, expertise, encouragement, and at times, sympathy. It has become a somewhat clichéd and expected thing to claim that a work would not be possible without such support. It is nonetheless true, at least from my experience, and I am indebted to all those who helped move the process along. First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my Maya teachers, colleagues, and friends who have selflessly devoted their time and knowledge to help carry out this project. Without their efforts, none of it would have ever gotten off the ground. I would like to particularly recognize in this regard don Vicente de León Abac, who, with patience and kindness, guided me through the complexity and poetry of K'iche' theology and ceremonialism. Without his wisdom, I would have missed much of the beauty of ancestral vision that is woven into the very fabric of the Popol Vuh. I dearly miss him. I would also like to acknowledge the profound influence that Antonio Ajtujal Vásquez had on this work. It was his kind and gentle voice that I often heard when I struggled at times to understand the ancient words of this text. -

A Dictionary of Mythology —

Ex-libris Ernest Rudge 22500629148 CASSELL’S POCKET REFERENCE LIBRARY A Dictionary of Mythology — Cassell’s Pocket Reference Library The first Six Volumes are : English Dictionary Poetical Quotations Proverbs and Maxims Dictionary of Mythology Gazetteer of the British Isles The Pocket Doctor Others are in active preparation In two Bindings—Cloth and Leather A DICTIONARY MYTHOLOGYOF BEING A CONCISE GUIDE TO THE MYTHS OF GREECE AND ROME, BABYLONIA, EGYPT, AMERICA, SCANDINAVIA, & GREAT BRITAIN BY LEWIS SPENCE, M.A. Author of “ The Mythologies of Ancient Mexico and Peru,” etc. i CASSELL AND COMPANY, LTD. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne 1910 ca') zz-^y . a k. WELLCOME INS77Tint \ LIBRARY Coll. W^iMOmeo Coll. No. _Zv_^ _ii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED INTRODUCTION Our grandfathers regarded the study of mythology as a necessary adjunct to a polite education, without a knowledge of which neither the classical nor the more modem poets could be read with understanding. But it is now recognised that upon mythology and folklore rests the basis of the new science of Comparative Religion. The evolution of religion from mythology has now been made plain. It is a law of evolution that, though the parent types which precede certain forms are doomed to perish, they yet bequeath to their descendants certain of their characteristics ; and although mythology has perished (in the civilised world, at least), it has left an indelible stamp not only upon modem religions, but also upon local and national custom. The work of Fruger, Lang, Immerwahr, and others has revolutionised mythology, and has evolved from the unexplained mass of tales of forty years ago a definite and systematic science. -

The Popol Vuh.Pdf

The Popol Vuh The Mythic and Heroic Sagas of the Kichés of Central America By Lewis Spence Published by David Nutt, at the Sign of the Phoenix, Long Acre, London [1908] PREFACE THE "Popol Vuh" is the New World's richest mythological mine. No translation of it has as yet appeared in English, and no adequate translation in any European language. It has been neglected to a certain extent because of the unthinking strictures passed upon its authenticity. That other manuscripts exist in Guatemala than the one discovered by Ximenes and transcribed by Scherzer and Brasseur de Bourbourg is probable. So thought Brinton, and the present writer shares his belief. And ere it is too late it would be well that these--the only records of the faith of the builders of the mystic ruined and deserted cities of Central America--should be recovered. This is not a matter that should be left to the enterprise of individuals, but one which should engage the consideration of interested governments; for what is myth to-day is often history to-morrow. LEWIS SPENCE. July 1908. {p. 213} THE POPOL VUH [The numbers in the text refer to notes at the end of the study] THERE is no document of greater importance to the study of the pre-Columbian mythology of America than the "Popol Vuh." It is the chief source of our knowledge of the mythology of the Kiché people of Central America, and it is further of considerable comparative value when studied in conjunction with the mythology of the Nahuatlacâ, or Mexican peoples. -

Prehispanic Art of Mesoamerica 7Th Grade Curriculum

Prehispanic Art of Mesoamerica 7 th Grade Curriculum Get Smart with Art is made possible with support from the William K. Bowes, Jr. Foundation, Mr. Rod Burns and Mrs. Jill Burns, and Daphne and Stuart Wells. Written by Sheila Pressley, Director of Education, and Emily K. Doman Jennings, Research Assistant, with support from the Education Department of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, © 2005. 1 st – 3 rd grade curriculum development by Gail Siegel. Design by Robin Weiss Design. Edited by Ann Karlstrom and Kay Schreiber. Get Smart with Art @ the de Young Teacher Advisory Committee 1 st – 3 rd Grade Renee Marcy, Creative Arts Charter School Lita Blanc, George R. Moscone Elementary School Sylvia Morales, Daniel Webster Elementary School Becky Paulson, Daniel Webster Elementary School Yvette Fagan, Dr. William L. Cobb Elementary School Alison Gray, Lawton Alternative School Margaret Ames, Alamo Elementary School Kim Walker, Yick Wo Elementary School May Lee, Alamo Elementary School 6th Grade Nancy Yin, Lafayette Elementary School Kay Corcoran, White Hill Middle School Sabrina Ly, John Yehall Chin Elementary School Donna Kasprowicz, Portola Valley School Seth Mulvey, Garfield Elementary School Patrick Galleguillos, Roosevelt Middle School Susan Glecker, Ponderosa School Steven Kirk, Francisco Middle School Karen Tom, Treasure Island School Beth Slater, Yick Wo Elementary School 7th Grade Pamela Mooney, Claire Lilienthal Alternative School th 4 Grade Geraldine Frye, Ulloa Elementary School Patrick Galleguillos, Roosevelt Middle School Joelene Nation, Francis Scott Key Elementary School Susan Ritter, Luther Burbank Middle School Mitra Safa, Sutro Elementary School Christina Wilder, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School Julia King, John Muir Elementary School Anthony Payne, Aptos Middle School Maria Woodworth, Alvarado Elementary School Van Sedrick Williams, Gloria R. -

The Popol I'uh

OPEN COURT Devoted to the Science of Religion, the Religion of Science, and the Exten- sion of the Religious Parliament Idea FOUNDED BY EDWARD C. HEGELER NOVEMBER, 1928 ,< ^ VOLUME XLII ^a;MBER 870 9rite 20 Cenit UBe Open Q)urt Publishing Company Wieboldt Hall, 339 East Chicago Aveaue Chicago, Illinois — THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 5750 ELLIS AVB^ CHICAGO THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHY OF EQUALITY By T. V. Smith Equality, in its present vague status, has lost much of the meaning that the founders of this country attached to it. In this book Mr. Smith has set out, in effect, to rescue from oblivion whatever truth the earlier doctrine contained. "Professor Smith writes as a philosopher and an historian. His reasoning is sound, his information accurate and his style clear and virile. The volume is a notable contribution to our political philosophy."—The New Republic. ^3.00, postpaid ^3.15 THE DEMOCRATIC WAY OF LIFE By T. V. Smith T. V. Smith in this book re-endows "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity," slogans of a goal that has never been reached—with some of the spirit of the days when they were magic words. Here is a brilliant commentary upon democracy as a way of life. ^1.75, postpaid ^1.85 AESTHETICS OF THE NOVEL By Van Meter Ames The fact that there is a decided relationship between literature and philoso- phy has been singularly ignored by past writers. Mr. Ames, believing that literary criticism cannot be sound unless it is placed on a philosophical basis, in this book has successfully correlated both subjects. -

Xbalanque's Marriage : a Commentary on the Q'eqchi' Myth of Sun and Moon Braakhuis, H.E.M

Xbalanque's marriage : a commentary on the Q'eqchi' myth of sun and moon Braakhuis, H.E.M. Citation Braakhuis, H. E. M. (2010, October 20). Xbalanque's marriage : a commentary on the Q'eqchi' myth of sun and moon. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16064 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral License: thesis in the Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/16064 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). XBALANQUE‘S MARRIAGE A dramatic moment in the story of Sun and Moon, as staged by Q‘eqchi‘ attendants of a course given in Tucurú, Alta Verapaz (photo R. van Akkeren) XBALANQUE‘S MARRIAGE A Commentary on the Q‘eqchi‘ Myth of Sun and Moon Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P. F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 20 oktober 2010 klokke 15 uur door Hyacinthus Edwinus Maria Braakhuis geboren te Haarlem in 1952 Promotiecommissie Promotoren: Prof. Dr. J. Oosten Prof. Dr. W. van Beek, Universiteit Tilburg Overige leden: Prof. Dr. N. Grube, Universiteit Bonn Dr. F. Jara Gómez, Universiteit Utrecht Dr. J. Jansen Cover design: Bruno Braakhuis Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede To the memory of Carlos Roberto Coy Oxom vi CONTENTS Contents vi Acknowledgement x General Introduction 1 1. Introduction to the Q’eqchi’ Sun and Moon Myth 21 Main Sources 21 Tale Structure 24 Main Actors 26 The Hero The Older Brother The Old Adoptive Mother The Father-in-Law The Maiden The Maiden‘s Second Husband 2. -

Popol-Vuh-The-Mayan-Book-Of

www.TaleBooks.com INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION (See illustration: Map of the Mayan region.) THE FIRST FOUR HUMANS, the first four earthly beings who were truly articulate when they moved their feet and hands, their faces and mouths, and who could speak the very language of the gods, could also see everything under the sky and on the earth. All they had to do was look around from the spot where they were, all the way to the limits of space and the limits of time. But then the gods, who had not intended to make and model beings with the potential of becoming their own equals, limited human sight to what was obvious and nearby. Nevertheless, the lords who once ruled a kingdom from a place called Quiche, in the highlands of Guatemala, once had in their possession the means for overcoming this nearsightedness, an ilbal, a "seeing instrument" or a "place to see"; with this they could know distant or future events. The instrument was not a telescope, not a crystal for gazing, but a book. The lords of Quiche consulted their book when they sat in council, and their name for it was Popol Vuh or "Council Book." Because this book contained an account of how the forefathers of their own lordly lineages had exiled themselves from a faraway city called Tulan, they sometimes described it as "the writings about Tulan." Because a later generation of lords had obtained the book by going on a pilgrimage that took them across water on a causeway, they titled it "The Light That Came from Across the Sea." And because the book told of events that happened before -

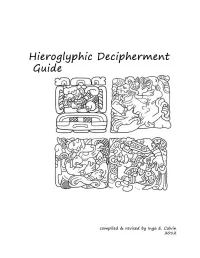

Hieroglyphic Decipherment Guide

Table of Contents Chronological Periods ...........................................................................................1 Classic Period Maya Sites .....................................................................................2 Classic Period & Modern Maya Languages Map ..................................................3 Evolution of Mayan Languages Dendrogram .......................................................4 Reading Order .......................................................................................................6 Phonetic Syllables .................................................................................................7 Numbers ..............................................................................................................13 Dates — Sacred Almanac of 260 Days ...............................................................14 Dates — Solar Calendar of 365 Days .................................................................15 Dates — Long Count ...........................................................................................16 Dates — Supplementary Series: Lords of the Night ............................................17 Dates — Supplementary Series: Lunar Series ....................................................18 Correlation of Maya & Christian Dates ................................................................19 Verbs — Inflectional Endings ..............................................................................21 Verbs — Accession .............................................................................................22 -

Mysteries of the Maize God Author(S): Bryan R

Mysteries of the Maize God Author(s): Bryan R. Just Source: Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol. 68 (2009), pp. 2-15 Published by: Princeton University Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25747104 . Accessed: 09/02/2014 20:47 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Princeton University Art Museum is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 209.129.16.124 on Sun, 9 Feb 2014 20:47:18 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions i. scene. Figure Cylinder vessel depicting a mythic Maya, El Zotz or vicinity (?), Peten, Guatemala. Late Classic, A.D. 650?800. cm. Ceramic with polychrome slip, h. 21.5 cm., diam. 15.0 Gift of Stephanie H. Bernheim and Leonard H. Bernheim Jr. in honor of Gillett G. Griffin (2005-127). This content downloaded from 209.129.16.124 on Sun, 9 Feb 2014 20:47:18 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Mysteries of theMaize God Bryan R. Just In 2005 the Princeton University Art Museum welcomed America.