Filed June 20, 2014 State Bar Court of California Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

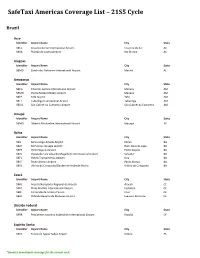

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Mmmtill SAN BERNARDINO R/UDAT

mMm till —m • « » • lift ••-• PV i '-•Si SAN BERNARDINO R/UDAT NA9127 .S248S35 1981 REGIONAL URBAN DESIGN ASSISTANCE TEAM/AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS/OCTOBER 8-12, 1981 .- —**<•«*•*?••>» isms vivf^s^^mSsSSSS^i^^^^SBSStSKSSS^ I JMHififi'aiffii?fs^iff •- ""-^--i* •+•-».«** • -~;:^>:-*. *-.•.*> [«•"!»IV*'•"•-'•••-' HHS!3«^9^BSEg?wH3B8MSBMn sfflBBW '. 'JU'I_Jl M* it '"THE" ' i i • ifcj 1H -"r'•'•':„ /,,«~ri~,^~w:^'3!3w*3^ • "'i"'—*^-* ; :*£*? lP sffi&9i?©5SV^^. i "^j:. - •HH fc^*;^^^ •' **^ S**\ "T^ *• •••••••••I •?.-$ Hll m WSBm p 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 ISSUES 8 RECOMMENDATIONS 10 CONTEXT 12 PROCESS FOR COMMUNITY CONSENSUS 16 ORGANIZING FOR GROWTH 19 PHYSICAL PLANNING COMPONENTS 36 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 50 eft to bo < 5 I INTRODUCTION WHAT IS R/UDAT AND WHY ARE THEY HERE? The Urban Planning and Design committee of The visit is a four-day, labor-intensive the American. Institute of Architects has process in which the members must quickly been sending Urban Design Assistance Teams assimilate facts, evaluate the existing to various American Cities since 1967. situation and arrive at a plan of action. The format of the visit consists of air, The San Bernardino Team is the 71st such automobile and bus tours to determine the team to be invited into a specific area to visual situation first hand; community deal with environmental and urban problems meeting and interviews to generate user which range in scale from a region to a input and to build community support; brain small town, and in type from recreational storming sessions to determine a direction areas to public policy and implementation and to develop implementable solutions; methods. -

58Th Southern California Journalism Awards Bill Rosendahl Public Service Award

FIFTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL5 SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA8 JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB JRNLad_LA Press Club Ad_2016.qxp_W&L 6/16/16 11:43 PM Page 1 We are proud to salute our valued comrade-in-arms ERIN BROCKOVICH Upon her receipt of the Los Angeles Press Club’s BILL ROSENDAHL PUBLIC SERVICE AWARD Erin is America’s consumer advocate and passionate crusader for environmental accountability from corporations and government. We are privileged to work side-by-side with her on so many essential causes, and look forward to many more years of mutual dedication to the prime interests of our fellow citizens. With great respect and gratitude, PERRY WEITZ ARTHUR M. LUXENBERG 212.558.5500 W E I T Z LUXENBERG www.weitzlux.com 7 0 0 B R O A D W A Y | N E W Y O R K , N Y 1 0&0 0 3 | B R A N C H O F F I C E S I N N E W J E R S E Y & C A L I F O R N I A th 58 ANNUAL SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS A Message From the President Celebrating a Record-Shattering Year Welcome to the 58th Annual Southern California Journalism Awards! Tonight we celebrate the efforts of all our nominees, whose work was selected from a record-shattering 1,011 submissions. The achievements of those receiving our highest honorary awards tonight are nothing less than astounding. Our President’s Award goes to Jarl Mohn, who is being recognized for his tremendous impact on television and radio networks, and who now serves as President and CEO of NPR. -

PROFILES in PURPOSE CBU Brand Represents 58 Years of Heritage and Countless Stories of Faith in Action California Baptist University C H O I R & O R C H E S T R a Dr

CALIFORNIA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY N O VE m B ER 2008 • VOLU m E 53 • ISSUE 3 PROFILES IN PURPOSE CBU brand represents 58 years of heritage and countless stories of faith in action California Baptist University C h o i r & o r C h e s t r a Dr. Gary Bonner, Conductor Presents an Evening of Delightful Christmas Music friDay, DeCemBer 12, 2008 | 7:30 pm Tickets available for $20 donation The Grove Community Church | Riverside, California For more information call satUrDay, DeCemBer 13, 2008 | 6:00 pm 951.343.4251 Harvest Christian Fellowship Church | Riverside, California C h o i r & o r C h e s t r a index of contents NVEO m B ER 2 0 0 8 the roundtable CALIFORNIA BAPTIST UNIVERSITY N O VE m B ER 2008 • VOLU m E 53 • ISSUE 3 EDITOR: Dr. Mark A. Wyatt MANAGING EDITOR: Karen Bergh ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Jeremy Zimmerman ART DIRECTOR: Edgar Garcia PHOTOGRAPHY: Michael J. Elderman, Kenton Jacobsen, Michael Kitada, Enoch Kim, Dr. Mark A. Wyatt, Trever Hoehne CONTRIBUTING WRITER(S): Micah McDaniel, David Noblett, Kendall DeWitt, Cynthia Wright, Carrie Smith SUBSCRIPTION INQUIRIES: California Baptist University 04 05 Division of Institutional Advancement PRESIDENT’S mESSAGE CBU NEwS Carrie Smith [email protected] 951.343.4439 ALUMNI AND DONOR INFORMATION: Division of Institutional Advancement 800.782.3382 www.calbaptist.edu/ia ADMISSIONS AND INFORMATION Department of Admissions 8432 Magnolia Avenue 08 10 Riverside, CA 92504-3297 [mIND], body AND SPIRIT CBU faculty 877.228.8866 The Roundtable is published three times annually for the alumni and friends of California Baptist University. -

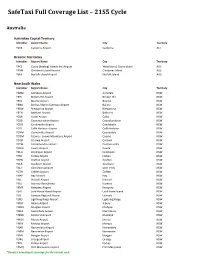

Safetaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Full Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Australia Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Morning Mania Contest, Clubs, Am Fm Programs Gorly's Cafe & Russian Brewery

Guide MORNING MANIA CONTEST, CLUBS, AM FM PROGRAMS GORLY'S CAFE & RUSSIAN BREWERY DOWNTOWN 536 EAST 8TH STREET [213] 627 -4060 HOLLYWOOD: 1716 NORTH CAHUENGA [213] 463 -4060 OPEN 24 HOURS - LIVE MUSIC CONTENTS RADIO GUIDE Published by Radio Waves Publications Vol.1 No. 10 April 21 -May 11 1989 Local Listings Features For April 21 -May 11 11 Mon -Fri. Daily Dependables 28 Weekend Dependables AO DEPARTMENTS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 CLUB LIFE 4 L.A. RADIO AT A GLANCE 6 RADIO BUZZ 8 CROSS -A -IRON 14 MORNING MANIA BALLOT 15 WAR OF THE WAVES 26 SEXIEST VOICE WINNERS! 38 HOT AND FRESH TRACKS 48 FRAZE AT THE FLICKS 49 RADIO GUIDE Staff in repose: L -R LAST WORDS: TRAVELS WITH DAD 50 (from bottom) Tommi Lewis, Diane Moca, Phil Marino, Linda Valentine and Jodl Fuchs Cover: KQLZ'S (Michael) Scott Shannon by Mark Engbrecht Morning Mania Ballot -p. 15 And The Winners Are... -p.38 XTC Moves Up In Hot Tracks -p. 48 PUBLISHER ADVERTISING SALES Philip J. Marino Lourl Brogdon, Patricia Diggs EDITORIAL DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Tommi Lewis Ruth Drizen, Tracey Goldberg, Bob King, Gary Moskowi z, Craig Rosen, Mark Rowland, Ilene Segalove, Jeff Silberman ART DIRECTOR Paul Bob CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Mark Engbrecht, ASSISTANT EDITOR Michael Quarterman, Diane Moca Rubble 'RF' Taylor EDITORIAL ASSISTANT BUSINESS MANAGER Jodi Fuchs Jeffrey Lewis; Anna Tenaglia, Assistant RADIO GUIDE Magazine Is published by RADIO WAVES PUBLICATIONS, Inc., 3307 -A Plco Blvd., Santa Monica, CA. 90405. (213) 828 -2268 FAX (213) 453 -0865 Subscription price; $16 for one year. For display advertising, call (213) 828 -2268 Submissions are welcomed. -

California State Power Plant Siting

DOCKET 09-AFC-10 DATE JAN 25 2010 RECD. FEB 02 2010 CEC HEADQUARTERS BUILDING 1516 9TH STREET, SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 Parties, Adjoining landowners, Interested governmental agencies, AND Published on the California Energy Commission Website U.S. Mail Public Advisor’s outreach efforts There are five members of the Energy Commission, two of whom have been appointed as the Committee that will conduct the certification process. The Committee will eventually issue a Presiding Member’s Proposed Decision (PMPD) containing recommendations on the proposed project to the full Energy Commission. • All decisions made in this case will be made solely on the basis of the public record. • No off‐the‐record contacts concerning substantive matters are permitted to take place between the parties and the Commissioners, their advisors, this Committee, or the Hearing Officer. • Contacts between the parties and the members of the Committee regarding a substantive matter must occur in a public forum or in a writing distributed to all the parties and made available to the public. • Purpose: to provide full disclosure to all participants of any information that may be used as a basis for the future Decision on this project. 5:00 General Information Public Advisor’s Office Presentation California Energy Commission Staff Presentation 6:00 Rice Solar Energy Project Rice Solar Energy LLC Presentation Issues Identification and Scheduling Discussion Public Question and Comment 7:00 Blythe & Palen Solar Power Projects Solar Millennium LLC Presentation Issues -

1. Outlet Name 2. Anchorage Daily News 3. KVOK-AM 4. KIAK-FM 5

1 1. Outlet Name 2. Anchorage Daily News 3. KVOK-AM 4. KIAK-FM 5. KKED-FM 6. KMBQ-FM 7. KMBQ-AM 8. KOTZ-AM 9. KOTZ-AM 10. KUHB-FM 11. KASH-FM 12. KFQD-AM 13. Dan Fagan Show - KFQD-AM, The 14. Anchorage Daily News 15. KBFX-FM 16. KIAK-FM 17. KKIS-FM 18. KOTZ-AM 19. KUDU-FM 20. KUDU-FM 21. KXLR-FM 22. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 23. KTVA-TV 24. 2 News Morning Edition - KTUU-TV 25. 2 News Weekend Late Edition - KTUU-TV 26. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 27. KTVA-TV 28. KTVA-TV 29. 11 News This Morning - KTVA-TV 30. 2 NewshoUr at 6 PM - KTUU-TV 31. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 32. 11 News at 10 PM - KTVA-TV 33. 11 News at 10 PM - KTVA-TV 34. KTVA-TV 35. KTVA-TV 36. 11 News at 10 PM - KTVA-TV 37. 11 News at 5 PM - KTVA-TV 38. 11 News at 6 PM - KTVA-TV 39. 2 News Weekend Late Edition - KTUU-TV 40. 2 News Weekend 5 PM Edition - KTUU-TV 41. KTUU-TV 42. KUAC-FM 43. KTUU-TV 44. KTUU-TV 45. 2 NewshoUr at 6 PM - KTUU-TV 46. KTUU-TV 2 47. KTVA-TV 48. KTUU-TV 49. Alaska Public Radio Network 50. KICY-AM 51. KMXT-FM 52. KYUK-AM 53. KTUU-TV 54. KTUU-TV 55. KTVA-TV 56. Anchorage Daily News 57. Anchorage Daily News 58. Fairbanks Daily News-Miner 59. -

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees Call Sign Fac. ID. # Service Class Community State Fee Code Fee Population KA2XRA 91078 AM D ALBUQUERQUE NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAA 55492 AM C KINGMAN AZ 0430$ 525 25,001 to 75,000 KAAB 39607 AM D BATESVILLE AR 0436$ 625 25,001 to 75,000 KAAK 63872 FM C1 GREAT FALLS MT 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KAAM 17303 AM B GARLAND TX 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KAAN 31004 AM D BETHANY MO 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAN-FM 31005 FM C2 BETHANY MO 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAP 63882 FM A ROCK ISLAND WA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAQ 18090 FM C1 ALLIANCE NE 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAR 63877 FM C1 BUTTE MT 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KAAT 8341 FM B1 OAKHURST CA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAY 33253 AM A LITTLE ROCK AR 0421$ 3,900 500,000 to 1.2 million KABC 33254 AM B LOS ANGELES CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABF 2772 FM C1 LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KABG 44000 FM C LOS ALAMOS NM 0450$ 2,875 150,001 to 500,000 KABI 18054 AM D ABILENE KS 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABK-FM 26390 FM C2 AUGUSTA AR 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KABL 59957 AM B OAKLAND CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABN 13550 AM B CONCORD CA 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABQ 65394 AM B ALBUQUERQUE NM 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABR 65389 AM D ALAMO COMMUNITY NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABU 15265 FM A FORT TOTTEN ND 0441$ 525 up to 25,000 KABX-FM 41173 FM B MERCED CA 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KABZ 60134 FM C LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KACC 1205 FM A ALVIN TX 0443$ 1,450 75,001 -

TV Channel 5-6 Radio Proposal

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 02-277 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-Ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple Ownership ) MM Docket No. 01-317 of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 ) Ways to Further Section 257 Mandate and To Build ) MB Docket No. 04-228 on Earlier Studies ) To: Office of the Secretary Attention: The Commission BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney Mark Lipp Paul H. Reynolds Bert Goldman Joseph Davis, P.E. Clarence Beverage Laura Mizrahi Lee Reynolds Alex Welsh SUMMARY The Broadcast Maximization Committee (“BMC”), composed of primarily of several consulting engineers and other representatives of the broadcast industry, offers a comprehensive proposal for the use of Channels 5 and 6 in response to the Commission’s solicitation of such plans. BMC proposes to (1) relocate the LPFM service to a portion of this spectrum space; (2) expand the NCE service into the adjacent portion of this band; and (3) provide for the conversion and migration of all AM stations into the remaining portion of the band over an extended period of time and with digital transmissions only. -

Suction Dredge Scoping Report-Appendix B-Press Release

DFG News Release Public Scoping Meetings Held to Receive Comments on Suction Dredge Permitting Program November 2, 2009 Contact: Mark Stopher, Environmental Program Manager, 530.225.2275 Jordan Traverso, Deputy Director, Office of Communications, Education and Outreach, 916.654.9937 The Department of Fish and Game (DFG) is holding public scoping meetings for input on its suction dredge permitting program. Three meetings will provide an opportunity for the public, interested groups, and local, state and federal agencies to comment on potential issues or concerns with the program. The outcome of the scoping meetings and the public comment period following the scoping meetings will help shape what is studied in the Subsequent Environmental Impact Report (SEIR). A court order requires DFG to conduct an environmental review of the program under the California Environmental Quality Act. DFG is currently prohibited from issuing suction dredge permits under the order issued July 9. In addition, as of August 6, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's signing of SB 670 (Wiggins) places a moratorium on all California instream suction dredge mining or the use of any such equipment in any California river, stream or lake, regardless of whether the operator has an existing permit issued by DFG. The moratorium will remain in effect until DFG completes the environmental review of its permitting program and makes any necessary updates to the existing regulations. The scoping meetings will be held in Fresno, Sacramento and Redding. Members of the public can provide comments in person at any of the following locations and times: Fresno: Monday, Nov. 16, 5 p.m.