Evaluating Titan2d Mass-Flow Model Using the 1963 Little Tahoma Peak Avalanches, Mount Rainier, Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON TEP~RJ\ ~EF's ' in Mount Rainier National Park

PUMICE AND OTHER PYROCLASTIC DEPOSITS IN Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON TEP~RJ\ ~EF's ' in Mount Rainier National Park. Pumice and scoria layers from Mount Rainier volcano (note layers R, L, D, and C) typically are stained to fairly strong brown or reddish brown; interbedded lithic ash deposits have relatively neutral but somewhat darker brownish-gray colors. Ash beds from other volcanoes (note beds marked 0, set Y, set P, and WI characteristically are lighter in color than the locally derived deposits that enclose them. S1te is in an alpine meadow near Williwakas Glacier on the southeast flank of Mount Ramier . PUMICE AND OTHER PYROCLASTIC DEPOSITS IN Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON By Donal R. Mullineaux 254924 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1326 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-600110 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE -1974 For sale by the Superintendent of· Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $1.35 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02550 Contents Page Abstract.................................................. 1 Introduction . 2 Previous work and acknowledgments . 4 Terminology . 6 General setting . 8 Brief description of tephra deposits . 8 Postglacial activity of Mount Rainier . 15 Eruptive history ........................ c............. 15 Volume............................................... 18 Kinds of eruptions . 18 Hazards from future eruptions of tephra . 21 Kinds of hazards . 21 Location . 22 Warning.............................................. 23 Ages of tephra layers and their use as marker beds . 23 Tephra from distant volcanoes . 27 Tephra layer 0 (Mazama ash) . 27 Distribution, thickness, and grain size . 29 Source and age . -

APNW-50 Tr' ORTH (4 -66

low AMC U. S. FOREST SERVICE tr ORTH (4 -66 EST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE • PORTLAND, OREGON APNW-50 March 1967 C PRIMARY MICROBIOLOGICAL SUCCESSION ON A LANDSLIDE cL OF ALPINE ORIGIN AT MOUNT RAINIER CD O by W. B. Bollen, Principal Soil Microbiologist CD a= K. C. Lu, Microbiologist 1--- CD J. M. Trappe, Principal Mycologist 77 R. F. Tarrant, Principal Soil Scientist CD 4 J. F. Franklin, Plant Ecologist In December 1963, immense masses of rock and debris broke loose from the north face of Little Tahoma Peak on the shoulder of Mount Rainier (Crandell and Fahnestock 1965).1/ Originating from a zone roughly 9,000 to 11,000 feet above sea level, the resulting series of avalanches swept down Emmons Glacier to deposit an estimated 14 million cubic yards of debris over 2 square miles of the glacier and the sparsely vegetated outwash valley below (fig. 1). Deposits reach thicknesses of about 100 feet in the valley, whose original elevation ranged from about 4,500 to 5,500 feet. Figure 1.--Northeast slope of Mount Rainier with Little Tahoma Peak on left-center skyline and avalanche de- posit in valley. 1/ — Names and dates in parentheses refer to Litera- ture Cited, p. 7. This nearly virgin, alpine "soil," laid in a valley surrounded by montane forest, presents superb opportunity for studies of soil development, plant succession, and distribution of pesticides and other environmental pollutants, especially when coupled with concur- rent observations of nearby terminal moraines left from recent recession of Emmons Glacier. -

Cascades Volcano Observatory

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY—REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS Mount Rainier—Living Safely With a Volcano in Your Backyard ajestic Mount Rainier M soars almost 3 miles (14,410 feet) above sea level and looms over the expanding suburbs of Seattle and Tacoma, Washington. Each year almost two million visitors come to Mount Rainier National Park to admire the volcano and its glaciers, alpine meadows, and forested ridges. However, the volcano’s beauty is deceptive— U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) research shows that Mount Rainier is one of our Nation’s most dangerous volcanoes. It has been the source of countless eruptions and volcanic mudflows (lahars) that have surged down valleys on its flanks and buried broad areas now densely populated. To help people live more safely with the volcano, USGS scientists are working closely with local communities, emergency managers, and the National Park Service. Mount Rainier, an active volcano currently at rest between eruptions, is the highest peak in the Cascade Range. Its edifice, capped by snow and 25 glaciers, has been built up by untold eruptions over the past 500,000 years. It last erupted in 1894–95, when small summit explosions were reported by observers in Seattle and Tacoma. Mount Rainier’s next eruption The flat floor of the Puyallup River valley near Orting, Washington, is formed by deposits of the 500-year-old might be of similar or larger size and Electron lahar, which surged down from Mount Rainier (in background). Lahars, or volcanic mudflows, are rapidly flowing slurries of mud and boulders that destroy or bury most manmade structures in their paths. -

7/' / 7? Title: Composition, Distribution and Succession of Subal Ne Meadows In

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jan Alan Henderson for theDoctor of Philosophy inPlant Ecology (Botany) presented on 9 7/' / 7? Title: Composition, Distribution and Succession of Subal ne Meadows in Mount Rainier National Park Abstract approved: --' Dr. W. W. Chilcote In 1970 a phytoscxiological reconnaissance consisting of 135 plots in the Subalpine Meadow Zone was made. These samples were sorted using an association table and several Alpine Zone and very early seral communities were set aside, An additional hundred plots taken by M. 3. Hamann were incorporated with these and compiled in another association table and com- bined in a two-dimensional ordination.This analysis yielded 18 major and 16 minor described community types which were clustered into five vegetation types. A key to the vegetation and community types is also presented. Soil moisture and temperature data were taken during 1971 and 1972 and are used to help characterize selected important communities. Soil moistures did not drop much during either season, although differences between corn- munities are apparent. The difference in temperatures (of the top 2 cm of soil) of the same selected communities were more striking. The Festuca domi- nated communities experienced soil temperatures over350C, while maximum temperatures in other communities rarely ranged over 20 C Low mght- time temperatures were relatively similar from conimumty to commumty, ranging from near freezing to about + 5° C. Several successional patterns were uncovered. In general the com- munities in the Low-Herbaceous Vegetation Type are early seral and are replaced by members of the Wet-Sedge, Lush-Herbaceous and the Dry-Grass Vegetation Types. -

Mapping Supraglacial Debris on Emmons Glacier Aerin Basehart

Mapping Supraglacial Debris on Emmons Glacier Aerin Basehart1, Sam Altenberger1, Michelle Koutnik2, and Claire Todd1 1 - Department of Geosciences, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA 98447 2 - Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, WA 98195 Abstract Sedimentological Results Remote-Sensing Data Analyses Debris-covered glaciers from around the world offer distinct environmental, climatic, Transects had a debris surface elevation range of ~150 feet, ranging from 5266 to 5431 feet for Six sediment units were qualitatively identified based on visually-derived color differences in and historical conditions from which to study the effects of debris on glacier-surface Transect 1, and from 5125 to 5275 feet for Transect 2. GPS elevation accuracy was consistently ±10-20 the debris cover as well as boulder density that was assigned as a relative measure as low, evolution. In general, for the ablation zone of a glacier to be covered by more than ~50% ft. For both transects, the eastern side of the glacier was higher in elevation (Figure 3). We found more moderate, or high. The unit with the largest area (unit D) is dominated by weathered andesite debris, the debris flux needs to be relatively high and the ice-flow rate needs to be angular samples on the eastern side of our transects (Figure 4). Sieving of fine-grained matrix samples that may be the remnants of the 1963 rockfall. All units except for D are oriented in the relatively low; this is the case for many Mt. Rainier glacier termini. On Emmons Glacier suggests a decrease in the presence of extremely fine-grained samples (smaller than 125 μm) near the direction of ice flow. -

Mount Rainier NATIONAL PARK

Mount Rainier NATIONAL PARK . WASHINGTON THE SEASONS Curving mountain roads demand careful driving. at Cougar Rock Campground. Camping through Observe posted speeds; drive defensively. Use out the park is allowed at designated sites only. From mid-June through October, the experi lower gears for steep hills. Help prevent traffic Also, for back-country camping, you will need a enced visitor comes prepared for cool and rainy jams by using turnouts and parking areas while back-country use permit, which is available at days as well as for those that are warm and sunny. observing wildlife or scenery. any ranger station. Build fires only in places where From November through May, heavy snowstorms fires are permitted. Dead and down wood only Motorcycles and motorbikes must be licensed, and are frequent. Annual snowfall at Paradise (5,420 may be used. Do not leave fires unattended; ex riders must comply with Washington State laws. feet) may total 80 feet; snow may lie as deep as tinguish them completely with water. Report un They are not allowed on park trails. 30 feet; 5 to 14 feet of snow may remain on the attended fires to a ranger. ground into June, and even 3 to 8 feet into July. Stop at overlooks marked "POINT OF INTEREST To keep bears and other animals from your food, AHEAD" for grand views and exhibits on Mount Wildflowers in the high meadows begin to blos you must store it in your car or suspended high in Rainier's features. som in mid-June in places where the snow has a tree. -

1 New Chronologic and Geomorphic Analyses of Debris Flows on Mount

New Chronologic and Geomorphic Analyses of Debris Flows on Mount Rainier, Washington By Ian Delaney Abstract Debris flows on Mount Rainier are thought to be increasing in frequency and magnitude in recent years, possibly due to retreating glaciers. These debris flows are caused by precipitation events or glacial outburst floods. Furthermore, as glaciers recede they leave steep unstable slopes of till providing the material needed for mass-wasting events. Little is known about the more distant history and downstream effects of these events. Field observations and/or aerial photograph of the Carbon River, Tahoma Creek, and White River drainages provide evidence of historic debris flow activity. The width and gradient of the channel on reaches of streams affected by debris flows is compared with reaches not affected by debris flows. In all reaches with field evidence of debris flows the average channel width is greater than in places not directly affected by debris flows. Furthermore, trends in width relate to the condition of the glacier. The stable Carbon Glacier with lots of drift at the terminus feeds the Carbon River, which has a gentle gradient and whose width remains relatively consistent over the period from 1952 to 2006. Conversely, the rapidly retreating Tahoma and South Tahoma Glaciers have lots of stagnant ice and feed the steep Tahoma Creek. Tahoma Creek’s width greatly increased, especially in the zone affect by debris flow activity. The rock-covered, yet relatively stable Emmons Glacier feeds White River, which shows relatively -

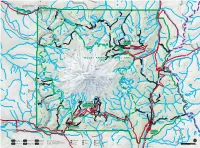

Moramap1.Pdf

To Wilkeson 13mi / 21km from CLEARWATER Carbon River Entrance k Obtain Climbing and Wilderness Road closed to vehicles beyond e this point. Road open to foot WILDERNESS e Camping Permits for the northwest r and bicycle traffic. Bicyclists must C r area of the park at Carbon River remain on the main road. e v Carbon e i Ranger Station. MT. BAKER-SNOQUALMIE NATIONAL FOREST o D R 165 rbon River T Ca rail (former road) r r 4mi e e C v Carbon River Entrance 6km i G v Chenuis Falls E i h e 410 R o G Lake t 1880ft k R e Carbon River i a e 573m n D e t I Eleanor e h u t Carbon River Rainforest Trail r R i k Tirzah Peak i C s h W e J 5208ft Scarface u e Adelaide Pigeon Peak r W E k n C 1587m 6108ft e L o C Lake e E k 1862m re C s N Oliver r r C Wallace Peak C A t e E e C G Ranger Falls o Sweet H Lake d k r F E D D a Peak e I N N e U ls t R I E s k l S Marjorie e a C P F Slide Mountain r E W T Lake C M e Green D 6339ft 2749ft N46° 58´ 42˝ S r Ipsut Creek O e e N 1932m 838m U Lake k I U e W121° 32´ 07˝ Florence Peak N Chenuis y R r C T Cr r k 5508ft e a A r A rb B e L 1679m g o EE I N Lakes rn n n F o b K Arthur Peak LA e I a T Lake H l Gove Peak S 5483ft R n k i C NORTH C l 5310ft Ethel a c v R 1671m u J r e E PARK 1619m W R V o e r iv H s S o e T n e ep r k de Lake K h k rl R in BURNT e an James A e C Howard Peak e d Y P PARK r r E Tyee Peak C LL e 5683ft Tr OW Natural D e ail S S k NORSE PEAK 1732m Spukwush TONE CLIFF Bridge N Tolmie Peak t C A u r Redstone R 5939ft s Alice e G p e Peak C 1810m I Falls k re BEAR e Norse Peak k WILDERNESS Eunice -

USGS Bulletin 2217

Field Guide to Hydrothermal Alteration in the White River Altered Area and in the Osceola Mudfl ow, Washington By David A. John, James J. Rytuba, Roger P. Ashley, Richard J. Blakely, James W. Vallance, Grant R. Newport, and Gary R. Heinemeyer Prepared for the Society of Economic Geologists Field Trip, November 6, 2003 Bulletin 2217 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Field Guide to Hydrothermal Alteration in the White River Altered Area and in the Osceola Mudflow, Washington By David A. John, James J. Rytuba, Roger P. Ashley, Richard J. Blakely, James W. Vallance, Grant R. Newport, and Gary R. Heinemeyer Bulletin 2217 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 1 U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2003 Electronic copies of this publication are available online at http://geopubs.wr.usgs.gov/bulletin/b2217/ Additional USGS publications can be found online at http://geology.usgs.gov/products.html For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS (1–888–275–8747) World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Published in the Western Region, Menlo Park, California Manuscript approved for publication October 25, 2003 2 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Road log from Enumclaw to the White River Altered Area and the Osceola Mudflow along the lower White River, Washington ............................................................................................ -

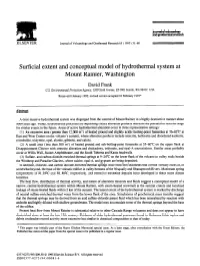

Surficial Extent and Conceptual Model of Hydrothermal System at Mount Rainier, Washington

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 65 ( 1995) 5 l-80 Surficial extent and conceptual model of hydrothermal system at Mount Rainier, Washington David Frank U.S.Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Sixth Avenue, ES-098 Seattle, WA 98101, USA Received 8 January 1992; revised version accepted 10 February 1993* Abstract A once massive hydrothermal system was disgorged from the summit of Mount Rainier in a highly destructive manner about 5000 years ago. Today, hydrothermal processes are depositing clayey alteration products that have the potential to reset the stage for similar events in the future. Areas of active hydrothermal alteration occur in three representative settings: ( 1) An extensive area (greater than 12,000 m*) of heated ground and slightly acidic boiling-point fumaroles at 76-82°C at East and West Craters on the volcano’s summit, where alteration products include smectite, halloysite and disordered kaolinite, cristobalite, tridymite, opal, alunite, gibbsite, and calcite. (2) A small area (less than 500 m’) of heated ground and sub-boiling-point fumaroles at 55-60°C on the upper flank at Disappointment Cleaver with smectite alteration and chalcedony, tridymite, and opal-A encrustations. Similar areas probably occur at Willis Wall, Sunset Amphitheater, and the South Tahoma and Kautz headwalls. (3) Sulfate- and carbon dioxide-enriched thermal springs at 9-24°C on the lower flank of the volcano in valley walls beside the Winthrop and Paradise Glaciers, where calcite, opal-A, and gypsum are being deposited. In addition, chloride- and carbon dioxide-enriched thermal springs issue from thin sediments that overlie Tertiary rocks at, or somewhat beyond, the base of the volcanic edifice in valley bottoms of the Nisqually and Ohanapecosh Rivers. -

Empowering a Generation of Climbers My First Ascent an Epic Climb of Mt

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG SPRING 2018 • VOLUME 112 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE in this issue: Empowering a Generation of Climbers An Interview with Lynn Hill My First Ascent Becoming Backwoods Barbie An Epic Climb of Mt. Rainier Via the Willis Wall tableofcontents Spring 2018 » Volume 112 » Number 2 Features The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about, and enjoy 24 Empowering a Generation of Climbers the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. An Interview with Lynn Hill 26 My First Ascent Becoming Backwoods Barbie 32 An Epic Climb of Mt. Rainier Via the Willis Wall Columns 7 MEMBER HIGHLIGHT Marcey Kosman 8 VOICES HEARD 24 1000 Words: The Worth of a Picture 11 PEAK FITNESS Developing a Personal Program 12 BOOKMARKS Fuel Up on Real Food 14 OUTSIDE INSIGHT A Life of Adventure Education 16 YOUTH OUTSIDE We’ve Got Gear for You 18 SECRET RAINIER 26 Goat Island Mountain 20 TRAIL TALK The Trail Less Traveled 22 CONSERVATION CURRENTS Climbers Wanted: Liberty Bell Needs Help 37 IMPACT GIVING Make the Most of Your Mountaineers Donation 38 RETRO REWIND To Everest and Beyond 41 GLOBAL ADVENTURES The Extreme Fishermen of Portugal’s Rota Vicentina 55 LAST WORD Empowerment 32 Discover The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining, or have joined and aren’t sure where to star, why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the Mountaineer uses: Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of CLEAR informational meetings at each of our seven branches. on the cover: Bam Mendiola, AKA “Backwoods Barbie” stands on the top of Mount Rainier. -

The Big One Opportunities That Rainier Has to Offer, Just in Time for You to Start Making Your Own Summer Hiking Plans

May + June 2011 » Washington Trails 21 On Trail Northwest Explorer » Living in the Northwest, we have no shortage of wilderness locations to escape into for a day—or a week. On any ol’ weekend, we could be climbing to the rim of smoldering Mount St. Helens, journeying through lush rain forests in the Olympics or trekking across the jagged ridges of the North Cascades. And while all of these places, and so many more locations, are outstanding, nothing quite compares with the majesty—or sheer immensity—of “The Mountain.” But when you think about hiking that Mountain, where do you even start? With over 240 miles of hiking trails (not counting mountaineering routes), spread over 378 square miles, there’s a lot to choose from. Add to that the incredible amount of scenic features—473 streams and rivers, 292 lakes, 122 waterfalls, 25 named glaciers, and more meadows, valleys, wildflowers, old-growth forest, and mind- numbing views than you can shake a trekking pole at—and the task of choosing a trail can no doubt be daunting. Thankfully, there are stacks of helpful guidebooks available to get you started. But even as great as most of those guidebooks are—full of inspiring photos and informative elevation profile graphs (a feature I particularly appreciate)—you’re still trying to whittle down from 50-plus options. And if you’re unfamiliar with The Mountain, what you’re really thinking Backpacking is, “Where do I go to get the really good stuff?” Well, this month, you’re in luck. From shorter starter trails to the granddaddy of round-the- mountain adventures, we’ll highlight five—and only five—of the most outstanding hiking the Big One opportunities that Rainier has to offer, just in time for you to start making your own summer hiking plans.