Monitoring and Modeling Ice-Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

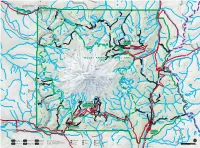

Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON TEP~RJ\ ~EF's ' in Mount Rainier National Park

PUMICE AND OTHER PYROCLASTIC DEPOSITS IN Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON TEP~RJ\ ~EF's ' in Mount Rainier National Park. Pumice and scoria layers from Mount Rainier volcano (note layers R, L, D, and C) typically are stained to fairly strong brown or reddish brown; interbedded lithic ash deposits have relatively neutral but somewhat darker brownish-gray colors. Ash beds from other volcanoes (note beds marked 0, set Y, set P, and WI characteristically are lighter in color than the locally derived deposits that enclose them. S1te is in an alpine meadow near Williwakas Glacier on the southeast flank of Mount Ramier . PUMICE AND OTHER PYROCLASTIC DEPOSITS IN Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON By Donal R. Mullineaux 254924 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1326 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-600110 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE -1974 For sale by the Superintendent of· Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $1.35 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02550 Contents Page Abstract.................................................. 1 Introduction . 2 Previous work and acknowledgments . 4 Terminology . 6 General setting . 8 Brief description of tephra deposits . 8 Postglacial activity of Mount Rainier . 15 Eruptive history ........................ c............. 15 Volume............................................... 18 Kinds of eruptions . 18 Hazards from future eruptions of tephra . 21 Kinds of hazards . 21 Location . 22 Warning.............................................. 23 Ages of tephra layers and their use as marker beds . 23 Tephra from distant volcanoes . 27 Tephra layer 0 (Mazama ash) . 27 Distribution, thickness, and grain size . 29 Source and age . -

APNW-50 Tr' ORTH (4 -66

low AMC U. S. FOREST SERVICE tr ORTH (4 -66 EST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE • PORTLAND, OREGON APNW-50 March 1967 C PRIMARY MICROBIOLOGICAL SUCCESSION ON A LANDSLIDE cL OF ALPINE ORIGIN AT MOUNT RAINIER CD O by W. B. Bollen, Principal Soil Microbiologist CD a= K. C. Lu, Microbiologist 1--- CD J. M. Trappe, Principal Mycologist 77 R. F. Tarrant, Principal Soil Scientist CD 4 J. F. Franklin, Plant Ecologist In December 1963, immense masses of rock and debris broke loose from the north face of Little Tahoma Peak on the shoulder of Mount Rainier (Crandell and Fahnestock 1965).1/ Originating from a zone roughly 9,000 to 11,000 feet above sea level, the resulting series of avalanches swept down Emmons Glacier to deposit an estimated 14 million cubic yards of debris over 2 square miles of the glacier and the sparsely vegetated outwash valley below (fig. 1). Deposits reach thicknesses of about 100 feet in the valley, whose original elevation ranged from about 4,500 to 5,500 feet. Figure 1.--Northeast slope of Mount Rainier with Little Tahoma Peak on left-center skyline and avalanche de- posit in valley. 1/ — Names and dates in parentheses refer to Litera- ture Cited, p. 7. This nearly virgin, alpine "soil," laid in a valley surrounded by montane forest, presents superb opportunity for studies of soil development, plant succession, and distribution of pesticides and other environmental pollutants, especially when coupled with concur- rent observations of nearby terminal moraines left from recent recession of Emmons Glacier. -

Cascades Volcano Observatory

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY—REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS Mount Rainier—Living Safely With a Volcano in Your Backyard ajestic Mount Rainier M soars almost 3 miles (14,410 feet) above sea level and looms over the expanding suburbs of Seattle and Tacoma, Washington. Each year almost two million visitors come to Mount Rainier National Park to admire the volcano and its glaciers, alpine meadows, and forested ridges. However, the volcano’s beauty is deceptive— U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) research shows that Mount Rainier is one of our Nation’s most dangerous volcanoes. It has been the source of countless eruptions and volcanic mudflows (lahars) that have surged down valleys on its flanks and buried broad areas now densely populated. To help people live more safely with the volcano, USGS scientists are working closely with local communities, emergency managers, and the National Park Service. Mount Rainier, an active volcano currently at rest between eruptions, is the highest peak in the Cascade Range. Its edifice, capped by snow and 25 glaciers, has been built up by untold eruptions over the past 500,000 years. It last erupted in 1894–95, when small summit explosions were reported by observers in Seattle and Tacoma. Mount Rainier’s next eruption The flat floor of the Puyallup River valley near Orting, Washington, is formed by deposits of the 500-year-old might be of similar or larger size and Electron lahar, which surged down from Mount Rainier (in background). Lahars, or volcanic mudflows, are rapidly flowing slurries of mud and boulders that destroy or bury most manmade structures in their paths. -

Mapping Supraglacial Debris on Emmons Glacier Aerin Basehart

Mapping Supraglacial Debris on Emmons Glacier Aerin Basehart1, Sam Altenberger1, Michelle Koutnik2, and Claire Todd1 1 - Department of Geosciences, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA 98447 2 - Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, WA 98195 Abstract Sedimentological Results Remote-Sensing Data Analyses Debris-covered glaciers from around the world offer distinct environmental, climatic, Transects had a debris surface elevation range of ~150 feet, ranging from 5266 to 5431 feet for Six sediment units were qualitatively identified based on visually-derived color differences in and historical conditions from which to study the effects of debris on glacier-surface Transect 1, and from 5125 to 5275 feet for Transect 2. GPS elevation accuracy was consistently ±10-20 the debris cover as well as boulder density that was assigned as a relative measure as low, evolution. In general, for the ablation zone of a glacier to be covered by more than ~50% ft. For both transects, the eastern side of the glacier was higher in elevation (Figure 3). We found more moderate, or high. The unit with the largest area (unit D) is dominated by weathered andesite debris, the debris flux needs to be relatively high and the ice-flow rate needs to be angular samples on the eastern side of our transects (Figure 4). Sieving of fine-grained matrix samples that may be the remnants of the 1963 rockfall. All units except for D are oriented in the relatively low; this is the case for many Mt. Rainier glacier termini. On Emmons Glacier suggests a decrease in the presence of extremely fine-grained samples (smaller than 125 μm) near the direction of ice flow. -

1 New Chronologic and Geomorphic Analyses of Debris Flows on Mount

New Chronologic and Geomorphic Analyses of Debris Flows on Mount Rainier, Washington By Ian Delaney Abstract Debris flows on Mount Rainier are thought to be increasing in frequency and magnitude in recent years, possibly due to retreating glaciers. These debris flows are caused by precipitation events or glacial outburst floods. Furthermore, as glaciers recede they leave steep unstable slopes of till providing the material needed for mass-wasting events. Little is known about the more distant history and downstream effects of these events. Field observations and/or aerial photograph of the Carbon River, Tahoma Creek, and White River drainages provide evidence of historic debris flow activity. The width and gradient of the channel on reaches of streams affected by debris flows is compared with reaches not affected by debris flows. In all reaches with field evidence of debris flows the average channel width is greater than in places not directly affected by debris flows. Furthermore, trends in width relate to the condition of the glacier. The stable Carbon Glacier with lots of drift at the terminus feeds the Carbon River, which has a gentle gradient and whose width remains relatively consistent over the period from 1952 to 2006. Conversely, the rapidly retreating Tahoma and South Tahoma Glaciers have lots of stagnant ice and feed the steep Tahoma Creek. Tahoma Creek’s width greatly increased, especially in the zone affect by debris flow activity. The rock-covered, yet relatively stable Emmons Glacier feeds White River, which shows relatively -

Moramap1.Pdf

To Wilkeson 13mi / 21km from CLEARWATER Carbon River Entrance k Obtain Climbing and Wilderness Road closed to vehicles beyond e this point. Road open to foot WILDERNESS e Camping Permits for the northwest r and bicycle traffic. Bicyclists must C r area of the park at Carbon River remain on the main road. e v Carbon e i Ranger Station. MT. BAKER-SNOQUALMIE NATIONAL FOREST o D R 165 rbon River T Ca rail (former road) r r 4mi e e C v Carbon River Entrance 6km i G v Chenuis Falls E i h e 410 R o G Lake t 1880ft k R e Carbon River i a e 573m n D e t I Eleanor e h u t Carbon River Rainforest Trail r R i k Tirzah Peak i C s h W e J 5208ft Scarface u e Adelaide Pigeon Peak r W E k n C 1587m 6108ft e L o C Lake e E k 1862m re C s N Oliver r r C Wallace Peak C A t e E e C G Ranger Falls o Sweet H Lake d k r F E D D a Peak e I N N e U ls t R I E s k l S Marjorie e a C P F Slide Mountain r E W T Lake C M e Green D 6339ft 2749ft N46° 58´ 42˝ S r Ipsut Creek O e e N 1932m 838m U Lake k I U e W121° 32´ 07˝ Florence Peak N Chenuis y R r C T Cr r k 5508ft e a A r A rb B e L 1679m g o EE I N Lakes rn n n F o b K Arthur Peak LA e I a T Lake H l Gove Peak S 5483ft R n k i C NORTH C l 5310ft Ethel a c v R 1671m u J r e E PARK 1619m W R V o e r iv H s S o e T n e ep r k de Lake K h k rl R in BURNT e an James A e C Howard Peak e d Y P PARK r r E Tyee Peak C LL e 5683ft Tr OW Natural D e ail S S k NORSE PEAK 1732m Spukwush TONE CLIFF Bridge N Tolmie Peak t C A u r Redstone R 5939ft s Alice e G p e Peak C 1810m I Falls k re BEAR e Norse Peak k WILDERNESS Eunice -

Surficial Extent and Conceptual Model of Hydrothermal System at Mount Rainier, Washington

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 65 ( 1995) 5 l-80 Surficial extent and conceptual model of hydrothermal system at Mount Rainier, Washington David Frank U.S.Environmental Protection Agency, 1200 Sixth Avenue, ES-098 Seattle, WA 98101, USA Received 8 January 1992; revised version accepted 10 February 1993* Abstract A once massive hydrothermal system was disgorged from the summit of Mount Rainier in a highly destructive manner about 5000 years ago. Today, hydrothermal processes are depositing clayey alteration products that have the potential to reset the stage for similar events in the future. Areas of active hydrothermal alteration occur in three representative settings: ( 1) An extensive area (greater than 12,000 m*) of heated ground and slightly acidic boiling-point fumaroles at 76-82°C at East and West Craters on the volcano’s summit, where alteration products include smectite, halloysite and disordered kaolinite, cristobalite, tridymite, opal, alunite, gibbsite, and calcite. (2) A small area (less than 500 m’) of heated ground and sub-boiling-point fumaroles at 55-60°C on the upper flank at Disappointment Cleaver with smectite alteration and chalcedony, tridymite, and opal-A encrustations. Similar areas probably occur at Willis Wall, Sunset Amphitheater, and the South Tahoma and Kautz headwalls. (3) Sulfate- and carbon dioxide-enriched thermal springs at 9-24°C on the lower flank of the volcano in valley walls beside the Winthrop and Paradise Glaciers, where calcite, opal-A, and gypsum are being deposited. In addition, chloride- and carbon dioxide-enriched thermal springs issue from thin sediments that overlie Tertiary rocks at, or somewhat beyond, the base of the volcanic edifice in valley bottoms of the Nisqually and Ohanapecosh Rivers. -

Sub-Section 4G.5 Puyallup Tribe All Hazard Mitigation Plan Volcanic

SUB-SECTION 4G.5 PUYALLUP TRIBE ALL HAZARD MITIGATION PLAN VOLCANIC HAZARD1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................... 1 IDENTIFICATION DESCRIPTION ................................................................................ 2 DEFINITION ............................................................................................................. 2 PROFILE ................................................................................................................... 5 LOCATION AND EXTENT ............................................................................................... 5 PLANNING AREA ...................................................................................................... 16 THE OCCURRENCES .................................................................................................. 16 IMPACTS ............................................................................................................... 18 VULNERABILITY TO PLANNING AREA....................................................................... 30 LAHAR FLOWS ......................................................................................................... 32 TEPHRA ................................................................................................................ 33 RESOURCE DIRECTORY .......................................................................................... 34 REGIONAL ............................................................................................................ -

Evaluating Titan2d Mass-Flow Model Using the 1963 Little Tahoma Peak Avalanches, Mount Rainier, Washington

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 139 (2005) 89–102 www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores Evaluating Titan2D mass-flow model using the 1963 Little Tahoma Peak avalanches, Mount Rainier, Washington M.F. Sheridana,*, A.J. Stintona, A. Patrab, E.B. Pitmanc, A. Bauerb, C.C. Nichitac aDepartment of Geology, 876 Natural Science Complex, University at Buffalo, Buffalo NY, 14260, USA bDepartment of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University at Buffalo, Buffalo NY, 14260, USA cDepartment of Mathematics, University at Buffalo, Buffalo NY, 14260, USA Accepted 29 June 2004 Abstract The Titan2D geophysical mass-flow model is evaluated by comparing its simulation results and those obtained from another flow model, FLOW3D, with published data on the 1963 Little Tahoma Peak avalanches on Mount Rainier, Washington. The avalanches, totaling approximately 10Â106 m3 of broken lava blocks and other debris, traveled 6.8 km horizontally and fell 1.8 km vertically (H/L=0.246). Velocities calculated from runup range from 24 to 42 m/s and may have been as high as 130 m/s while the avalanches passed over Emmons Glacier. Titan2D is a code for an incompressible Coulomb continuum; it is a depth-averaged, dshallow-waterT, granular-flow model. The conservation equations for mass and momentum are solved with a Coulomb-type friction term at the basal interface. The governing equations are solved on multiple processors using a parallel, adaptive mesh, Godunov scheme. Adaptive gridding dynamically concentrates computing power in regions of special interest; mesh refinement and coarsening key on the perimeter of the moving avalanche. The model flow initiates as a pile defined as an ellipsoid by a height (z) and an elliptical base defined by radii in the x and y planes. -

Mount Rainier National Park Science Brief

Mount Rainier National Park Science Brief Melting the rocky terminus of Emmons Glacier Peter L. Moore1 ([email protected]), Leah I. Nelson2, and Theresa M. Dits3 1Department of Natural Resource Ecology & Management, Iowa State University; 2Department of Geology, Carleton College; 3Department of Geological & Atmospheric Sciences, Iowa State University. Most views of Mount Rainier from the Sunrise area are Rainier, but is becoming more widespread in mountainous dominated – at least in part – by Emmons Glacier, the areas where glaciers are thinning. largest glacier in the United States outside of Alaska. Like the other large glaciers on Rainier’s north slope (Carbon This “supraglacial” rock debris has important and complex Glacier and Winthrop Glacier), the front end, or terminus, impacts on the response of glaciers to climate changes. of Emmons glacier is covered in rock debris. Some of this Whereas snow and ice keep cool by reflecting much of the rock debris comes from periodic rock falls from the incoming sunshine back into the atmosphere, rock debris neighboring ridges, while other debris is scraped from rock absorbs most of the incoming radiation. As the rock ridges that the glacier flows over. Regardless of the source, blanket heats up, it conducts some of that heat to the ice to melting concentrates the debris at the glacier surface as the allow melting to proceed. But if the debris is more than a ice flows downslope, resulting in a nearly-continuous few inches thick, the debris acts like a blanket that slows debris-cover over the lower half-mile of the glacier (see melting overall. -

MOUNT ACTIVE CASCADE VOLCANO I28 P RAINIER

N94-33992 = (NASA-CR-195893) MOUNT RAINIER ACTIVE CASCADE VOLCANO (NAS-NRC) I I28 p I .Unclas G3/46 0008798 z 4 _E m MOUNT INIER Active Cascade Volcano MOUNT Active Cascade Volcano Research Strategies for Mitigating Risk from a High, Snow-Clad Volcano in a Populous Region U.S. Geodynamics Committee Board on Earth Sciences and Resources Commission on Geosciences, Environment, and Resources National Research Council NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C. 1994 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Governing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This report has been reviewed by a group other than the authors according to proce- dures approved by a Report Review Committee consisting of members of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine. Support for this study was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy, National /,i" Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Science Foundation, and U.S. Geological Survey. L_rary of Congress Catalog Card No. 94-66300 International Standard Book Number 0-309-05083-9 Copies of this report are available from: National Academy Press 2101 Constitution Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20418 800-624-6242 202-334-3313 (in the Washington Metropolitan Area) Cover photograph of Mount Rainier courtesy of Richard S. -

The Yodelyodel

The mountains will always be there; the trick is to make sure you are, too. —Hervey Voge TheThe YodelYodel Volume 16, Issue 2 October, 2009 Mutineers Touch the Top! In This Issue: —Geocaching by Elisha Z —p.4 —Lopez Bike Ride by Diane S. — p.5 —OSAT Quick Ref — p. 6 —Discovering OSAT by Doug L — p.7 —Mount Rainier by Robert S— p.8 —what themountain whispered by Dawn K —p.9 —49 & Finished by Rik A —p.10 L to R: GCC Alums Janet S., Dan L., Bob S., Lucinda T., Jeff H., Matt M., Brian W., Mark L., Bill S., and Rob C. —Del Campo Adventure by Anna O.—p.13 by Janet M. —-Ross Lake: Things Great & Small by Louisa P—p.15 Bob S. (ponytail Bob) and I were unable to summit Mt. Rainier with our class in 2008 and, given the size of the 2009 class, knew we would most likely not be able to tag along on one of their climbs. So —Photorama in March I sent out a feeler e-mail to see just how many prior students and OSAT members would be —p.19 interested in a climb not linked with the class. Within a week, I had eleven names. Peter J .(Peeta) got ONE STEP AT A involved and we started planning. Bob and I were in training mode, so we began adding a Monday night Tiger to the Thursday night meeting. Dan L. joined one of these Mondays and we started talking TIME (OSAT) about developing an official climb.