1 New Chronologic and Geomorphic Analyses of Debris Flows on Mount

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON TEP~RJ\ ~EF's ' in Mount Rainier National Park

PUMICE AND OTHER PYROCLASTIC DEPOSITS IN Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON TEP~RJ\ ~EF's ' in Mount Rainier National Park. Pumice and scoria layers from Mount Rainier volcano (note layers R, L, D, and C) typically are stained to fairly strong brown or reddish brown; interbedded lithic ash deposits have relatively neutral but somewhat darker brownish-gray colors. Ash beds from other volcanoes (note beds marked 0, set Y, set P, and WI characteristically are lighter in color than the locally derived deposits that enclose them. S1te is in an alpine meadow near Williwakas Glacier on the southeast flank of Mount Ramier . PUMICE AND OTHER PYROCLASTIC DEPOSITS IN Mount Rainier National Park, WASHINGTON By Donal R. Mullineaux 254924 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1326 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-600110 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE -1974 For sale by the Superintendent of· Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $1.35 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02550 Contents Page Abstract.................................................. 1 Introduction . 2 Previous work and acknowledgments . 4 Terminology . 6 General setting . 8 Brief description of tephra deposits . 8 Postglacial activity of Mount Rainier . 15 Eruptive history ........................ c............. 15 Volume............................................... 18 Kinds of eruptions . 18 Hazards from future eruptions of tephra . 21 Kinds of hazards . 21 Location . 22 Warning.............................................. 23 Ages of tephra layers and their use as marker beds . 23 Tephra from distant volcanoes . 27 Tephra layer 0 (Mazama ash) . 27 Distribution, thickness, and grain size . 29 Source and age . -

Outline for Thesis

THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Thomas H. Nylen for the Master of Science in Geology presented October 25, 2001, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: _______________________________________ Andrew G. Fountain, Chair _______________________________________ Scott F. Burns _______________________________________ Christina L. Hulbe _______________________________________ Keith S. Hadley Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENTAL APPROVAL: _______________________________________ Michael L. Cummings, Chair Department of Geology ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Thomas H. Nylen for the Master of Science in Geology presented October 25, 2001. Title: Spatial and Temporal Variations of Glaciers (1913-1994) on Mt. Rainier and the Relation with Climate Databases have been constructed for the purpose of studying glacier changes at Mt. Rainier. Glacier cover on Mt. Rainier decreased 18.5% (112.3 km2 to 88.1 km2) between 1913 and 1971 at a rate of about -0.36 km2 a-1. The total area in 1994 was 87.4 km2, which equates to a rate of -0.03 km2 a-1 since 1971. Glaciers with southerly aspect lost significantly more area than those with a northerly aspect, 26.5% and 17.5% of the total area, respectively. Measured and estimated total volumes for Mt. Rainier glaciers also decreased. From 1913 to 1971 the total volume decreased 22.7% from 5.62 km3 to 4.34 km3 and from 1971 to 1994 decreased 3.1% to 4.21 km3. Nisqually Glacier shows three cycles of retreat and advance but an overall loss of 0.44 km2 since 1931. Cross-correlation with snowfall suggests about a decade response time for the glaciers. -

The Recession of Glaciers in Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

THE RECESSION OF GLACIERS IN MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK, WASHINGTON C. FRANK BROCKMAN Mount Rainier National Park FOREWORD One of the most outstanding features of interest in Mount Rainier National Park is the extensive glacier system which lies, almost entirely, upon the broad flanks of Mount Rainier, the summit of which is 14,408 feet above sea-level. This glacier system, numbering 28 glaciers and aggregating approximately 40-45 square miles of ice, is recognized as the most extensive single peak glacier system in continental United States.' Recession data taken annually over a period of years at the termini of six representative glaciers of varying type and size which are located on different sides of Mount Rainier are indicative of the rela- tive rate of retreat of the entire glacier system here. At the present time the glaciers included in this study are retreating at an average rate of from 22.1 to 70.4 feet per year.2 HISTORY OF INVESTIGATIONS CONDUCTED ON THE GLACIERS OF MOUNT RAINIER Previous to 1900 glacial investigation in this area was combined with general geological reconnaissance surveys on the part of the United States Geological Survey. Thus, the activities of S. F. Em- mons and A. D. Wilson, of the Fortieth Parallel Corps, under Clarence King, was productive of a brief publication dealing in part with the glaciers of Mount Rainier.3 Twenty-six years later, in 1896, another United States Geological Survey party, which included Bailey Willis, I. C. Russell, and George Otis Smith, made additional SCircular of General Information, Mount Rainier National Park (U.S. -

APNW-50 Tr' ORTH (4 -66

low AMC U. S. FOREST SERVICE tr ORTH (4 -66 EST FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE • PORTLAND, OREGON APNW-50 March 1967 C PRIMARY MICROBIOLOGICAL SUCCESSION ON A LANDSLIDE cL OF ALPINE ORIGIN AT MOUNT RAINIER CD O by W. B. Bollen, Principal Soil Microbiologist CD a= K. C. Lu, Microbiologist 1--- CD J. M. Trappe, Principal Mycologist 77 R. F. Tarrant, Principal Soil Scientist CD 4 J. F. Franklin, Plant Ecologist In December 1963, immense masses of rock and debris broke loose from the north face of Little Tahoma Peak on the shoulder of Mount Rainier (Crandell and Fahnestock 1965).1/ Originating from a zone roughly 9,000 to 11,000 feet above sea level, the resulting series of avalanches swept down Emmons Glacier to deposit an estimated 14 million cubic yards of debris over 2 square miles of the glacier and the sparsely vegetated outwash valley below (fig. 1). Deposits reach thicknesses of about 100 feet in the valley, whose original elevation ranged from about 4,500 to 5,500 feet. Figure 1.--Northeast slope of Mount Rainier with Little Tahoma Peak on left-center skyline and avalanche de- posit in valley. 1/ — Names and dates in parentheses refer to Litera- ture Cited, p. 7. This nearly virgin, alpine "soil," laid in a valley surrounded by montane forest, presents superb opportunity for studies of soil development, plant succession, and distribution of pesticides and other environmental pollutants, especially when coupled with concur- rent observations of nearby terminal moraines left from recent recession of Emmons Glacier. -

Cascades Volcano Observatory

U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY—REDUCING THE RISK FROM VOLCANO HAZARDS Mount Rainier—Living Safely With a Volcano in Your Backyard ajestic Mount Rainier M soars almost 3 miles (14,410 feet) above sea level and looms over the expanding suburbs of Seattle and Tacoma, Washington. Each year almost two million visitors come to Mount Rainier National Park to admire the volcano and its glaciers, alpine meadows, and forested ridges. However, the volcano’s beauty is deceptive— U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) research shows that Mount Rainier is one of our Nation’s most dangerous volcanoes. It has been the source of countless eruptions and volcanic mudflows (lahars) that have surged down valleys on its flanks and buried broad areas now densely populated. To help people live more safely with the volcano, USGS scientists are working closely with local communities, emergency managers, and the National Park Service. Mount Rainier, an active volcano currently at rest between eruptions, is the highest peak in the Cascade Range. Its edifice, capped by snow and 25 glaciers, has been built up by untold eruptions over the past 500,000 years. It last erupted in 1894–95, when small summit explosions were reported by observers in Seattle and Tacoma. Mount Rainier’s next eruption The flat floor of the Puyallup River valley near Orting, Washington, is formed by deposits of the 500-year-old might be of similar or larger size and Electron lahar, which surged down from Mount Rainier (in background). Lahars, or volcanic mudflows, are rapidly flowing slurries of mud and boulders that destroy or bury most manmade structures in their paths. -

Carbon River Access Management Plan

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Washington Fish and Wildlife Office 510 Desmond Dr. SE, Suite 102 Lacey, Washington 98 503 APR 2 6 20ll In Reply Refer To: 13410-2010-F-0488 Memorandum To: Superintendent, Mount Rainier National Park Ashford, Washington From: Manager, Washington Fish and Wildlife Lacey, Washington Subject: Biological Opinion for the Carbon River Access Management Plan This document transmits the Fish and Wildlife Service's Biological Opinion based on our review of the proposed Carbon River Access Managernent Plan to be implemented in Mount Rainier National Park, Pierce County, Washington. We evaluated effects on the threatened northern spotted owl (Sfrlx occidentalis caurina),marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus),bttll trout (Salvelinus confluentus), and designated bull trout critical habitat in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (Act) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). Your July 29,2010 request for formal consultation was received on August 2,2010. This Biological Opinion is based on information provided in the June 28, 2010 Biological Assessment and on other information and correspondence shared between our respective staff. Copies of all correspondence regarding this consultation are on file at the Washington Fish and Wildlife Office in Lacey, Washington. If you have any questions about this mernorandum, the attached Biological Opinion, or your responsibilities under the Act, please contact Vince Harke at (360) 753-9529 or Carolyn Scafidi at (360) 753-4068. Endangered Species Act - Section 7 Consultation BIOLOGICAL OPINION U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Reference: 13410-2010-F-0488 Carbon River Access Management Plan Mount Rainier National Park Pierce County, Washington Agency: National Park Service Consultation Conducted By: U.S. -

Mapping Supraglacial Debris on Emmons Glacier Aerin Basehart

Mapping Supraglacial Debris on Emmons Glacier Aerin Basehart1, Sam Altenberger1, Michelle Koutnik2, and Claire Todd1 1 - Department of Geosciences, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, WA 98447 2 - Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, WA 98195 Abstract Sedimentological Results Remote-Sensing Data Analyses Debris-covered glaciers from around the world offer distinct environmental, climatic, Transects had a debris surface elevation range of ~150 feet, ranging from 5266 to 5431 feet for Six sediment units were qualitatively identified based on visually-derived color differences in and historical conditions from which to study the effects of debris on glacier-surface Transect 1, and from 5125 to 5275 feet for Transect 2. GPS elevation accuracy was consistently ±10-20 the debris cover as well as boulder density that was assigned as a relative measure as low, evolution. In general, for the ablation zone of a glacier to be covered by more than ~50% ft. For both transects, the eastern side of the glacier was higher in elevation (Figure 3). We found more moderate, or high. The unit with the largest area (unit D) is dominated by weathered andesite debris, the debris flux needs to be relatively high and the ice-flow rate needs to be angular samples on the eastern side of our transects (Figure 4). Sieving of fine-grained matrix samples that may be the remnants of the 1963 rockfall. All units except for D are oriented in the relatively low; this is the case for many Mt. Rainier glacier termini. On Emmons Glacier suggests a decrease in the presence of extremely fine-grained samples (smaller than 125 μm) near the direction of ice flow. -

What Can We Learn from Mount Rainier Meltwater? Claire Todd Pacific Lutheran University

What can we learn from Mount Rainier meltwater? Claire Todd Pacific Lutheran University Emmons Glacier, White River What can we learn from Mount Rainier meltwater? Claire Todd Pacific Lutheran University Luke Weinbrecht, Elyssa Tappero, David Horne, Bryan Donahue, Matt Schmitz, Matthew Hegland, Michael Vermeulen, Trevor Perkins, Nick Lorax, Kristiana Lapo, Greg Pickard, Cameron Wiemerslage, Ryan Ransavage, Allie Jo Koester, Nathan Page, Taylor Christensen, Isaac Moening-Swanson, Riley Swanson, Reed Gunstone, Aaron Steelquist, Emily Knutsen, Christina Gray, Samantha Harrison, Kyle Bennett, Victoria Benson, Adriana Cranston, Connal Boyd, Sam Altenberger, Rainey Aberle, Alex Yannello, Logan Krehbiel, Hannah Bortel, Aerin Basehart Emmons Glacier, White River Why meltwater? • Provides a window into the subglacial environment • Water storage and drainage • Sediment generation, storage and evacuation • Interaction with the hydrothermal system Geologic Hazards Emmons Glacier, • Outburst floods and debris flows White River Volcanic hazards • (e.g., Brown, 2002; Lawler et al., 1996; Collins, 1990) Field Sites - criteria • As close to the terminus as possible, to avoid • Contribution to discharge from non-glacial streams (snowmelt) • Impact of atmospheric mixing on water chemistry • Deposition or entrainment of sediment outside of the Emmons Glacier, subglacial environment White River • Single channel, to achieve • Complete (as possible) representation of the subglacial environment Carbon Emmons Glacier, White River Glacier Field Sites – Channel -

Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

NATIONAL PARK . WASHINGTON MOUNT RAINIER WASHINGTON CONTENTS "The Mountain" 1 Wealth of Gorgeous Flowers 3 The Forests 5 How To Reach the Park 8 By Automobile 8 By Railroad and Bus 11 By Airplane 11 Administration 11 Free Public Campgrounds 11 Post Offices 12 Communication and Express Service 12 Medical Service 12 Gasoline Service 12 What To Wear 12 Trails 13 Fishing 13 Mount Rainier Summit Climb 13 Accommodations and Expenses 15 Summer Season 18 Winter Season 18 Ohanapecosh Hot Springs 20 Horseback Trips and Guide Service 20 Transportation 21 Tables of Distances 23 Principal Points of Interest 28 References 32 Rules and Regulations 33 Events of Historical Importance 34 Government Publications 35 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • Harold L. Ickes, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Arno B. Cammerer, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE • 1938 AN ALL-YEAR PARK Museums.—The park museum, headquarters for educational activities, MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK may be fully enjoyed throughout the and office of the park naturalist are located in the museum building at year. The summer season extends from early June to early November; the Longmire. Natural history displays and wild flower exhibits are main winter ski season, from late November well into May. All-year roads make tained at Paradise Community House, Yakima Park Blockhouse, and the park always accessible. Longmire Museum. Nisquaiiy Road is open to Paradise Valley throughout the year. During Hikes from Longmire.—Free hikes, requiring 1 day for the round trip the winter months this road is open to general traffic to Narada Falls, 1.5 are conducted by ranger naturalists from the museum to Van Trump Park, miles by trail from Paradise Valley. -

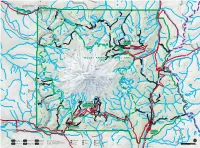

Moramap1.Pdf

To Wilkeson 13mi / 21km from CLEARWATER Carbon River Entrance k Obtain Climbing and Wilderness Road closed to vehicles beyond e this point. Road open to foot WILDERNESS e Camping Permits for the northwest r and bicycle traffic. Bicyclists must C r area of the park at Carbon River remain on the main road. e v Carbon e i Ranger Station. MT. BAKER-SNOQUALMIE NATIONAL FOREST o D R 165 rbon River T Ca rail (former road) r r 4mi e e C v Carbon River Entrance 6km i G v Chenuis Falls E i h e 410 R o G Lake t 1880ft k R e Carbon River i a e 573m n D e t I Eleanor e h u t Carbon River Rainforest Trail r R i k Tirzah Peak i C s h W e J 5208ft Scarface u e Adelaide Pigeon Peak r W E k n C 1587m 6108ft e L o C Lake e E k 1862m re C s N Oliver r r C Wallace Peak C A t e E e C G Ranger Falls o Sweet H Lake d k r F E D D a Peak e I N N e U ls t R I E s k l S Marjorie e a C P F Slide Mountain r E W T Lake C M e Green D 6339ft 2749ft N46° 58´ 42˝ S r Ipsut Creek O e e N 1932m 838m U Lake k I U e W121° 32´ 07˝ Florence Peak N Chenuis y R r C T Cr r k 5508ft e a A r A rb B e L 1679m g o EE I N Lakes rn n n F o b K Arthur Peak LA e I a T Lake H l Gove Peak S 5483ft R n k i C NORTH C l 5310ft Ethel a c v R 1671m u J r e E PARK 1619m W R V o e r iv H s S o e T n e ep r k de Lake K h k rl R in BURNT e an James A e C Howard Peak e d Y P PARK r r E Tyee Peak C LL e 5683ft Tr OW Natural D e ail S S k NORSE PEAK 1732m Spukwush TONE CLIFF Bridge N Tolmie Peak t C A u r Redstone R 5939ft s Alice e G p e Peak C 1810m I Falls k re BEAR e Norse Peak k WILDERNESS Eunice -

Page 85 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 110C Main Fork of Ohanapecosh

Page 85 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 110c main fork of Ohanapecosh River to the quarter and one-half acres, as generally depicted on the section line of section 9, township 14 north, map entitled ‘‘Mount Rainier National Park range 10 east, Willamette meridian; thence west- Proposed 1987 Boundary Adjustments’’, num- erly along the quarter section line of sections 9, bered 105–80,010B and dated January 1987, which 8, and 7 to the west boundary of said township; shall be on file and available for public inspec- thence due west to the right or west bank of tion in the Washington office of the National Muddy Fork of the Cowlitz River; thence north- Park Service, United States Department of the erly along the right bank of said Muddy Fork to Interior and at Mount Rainier National Park. a point exactly due east of post numbered 34 on (b) Forest boundary adjustment the south boundary of Mount Rainier National The boundaries of the Snoqualmie National Park as surveyed in 1908; thence due west to said Forest and of the Gifford Pinchot National For- post numbered 34; thence along the boundary of est, are hereby revised to include in the Sno- said park as surveyed in 1908 to post numbered qualmie National Forest approximately thirty- 35; thence easterly along the south boundary of one and one-half acres, to exclude from the Sno- said national park as surveyed in 1908 to the qualmie National Forest approximately thirty southeast corner thereof; thence northerly along acres, and to exclude from the Gifford Pinchot the east boundary of said national park as sur- National Forest approximately two hundred and veyed in 1908 to post numbered 59; thence along ten acres, as generally depicted on a map enti- the east boundary of said park as revised by sec- tled ‘‘Mount Rainier National Park Proposed tion 107 of this title, northerly to the point of 1987 Boundary Adjustments’’, numbered beginning. -

1912 the Mountaineers

The Mountaineer. Volume Five Nineteen Hundred Twelve h611, •• , ,, The Mountaineen Sea11le. Wa1hla1100 :J1'.)1'1zec1 bv G oog I e 2,-�a""" ...._� _..,..i..c.. tyJ Vi) Copyright 1912 The Mountaineers Din,tiZ<'d by Google CONTENTS Page Greeting ................... ................................John Muir .......................................... Greeting ..................................................... Enos Mills ........................................ The Higher Functions of a Mountain Club................................................... \ Wm. Frederic Bade.......................... 9 Little Tahoma ............ ............................. .Edmond S. Meany............................ 13 Mountaineer Outing of 1912 on north side of Mt. Rainier....................... Mary Paschall ................................... 14 Itinerary of Outing of 1912................... .Charles S. Gleason........................... 26 The Ascent of Mt. Rainier.................... £. M.Hack ........................................ 28 Grand Park .............................................. 1=dmond S. Meany............................ 36 A New Route up Mt. Rainier.............. 'Jara Keen ........................................ 37 Naches Pass .............................................. Edmond S. Meany....... ,.................... 40 Undescribed Glaciers of Mt. Rainier .. Fran,ois Matthes ............................. 42 Thermal Caves ....................................... J. B. Flett .......................................... 58 Change in Willis