Long-Term Implications of Humanitarian Responses the Case of Chennai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View hSisetoarych State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The St at e Indust ries Promot ion Contents State Industries Promotion Corporat ion of Tamil Nadu Featured content Corporation of Tamil Nadu Limit ed (SIPCOT)(Tamil: Limited Current events Random article Donate to Wikipedia Interaction ( )), Help Limited is an institution owned by the About Wikipedia government of Tamil Nadu Community portal Recent changes Contents [hide] Headquart ers Rukmani Lakshmipathy Contact Wikipedia 1 History Road,Egmore,Chennai - 600 008 . Toolbox 2 Functions 3 SIPCOT Estates Key peo ple Thiru.Dr.Niranjan Mardi, Print/export 4 See also IAS,Principal Secretary/Chairman & 5 References Languages MD for SIPCOT 6 External links Owner(s) Government of Tamil 7 Other links Edit links Nadu Websit e in History [edit] http://www.sipcot.com The State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu Limited (SIPCOT) was formed in the year 1971, to promote industrial growth in the State and to advance term loans to medium and large industries [1] Functions [edit] The Functions of State Industries Promotion Corporation of Tamil Nadu Limited (SIPCOT) are:[2] Development of industrial complexes/parks/growth centers with basic infrastructure facilities Establishing sector-specific Special Economic Zones (SEZs); Implementation of Special infrastructure Projects; SIPCOT Estates [edit] SIPCOT has established industrial complexes in 16 areas, according to the SIPCOT webpage. -

Telephone Numbers

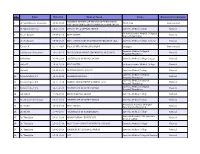

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY THANJAVUR IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS DISTRICT EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTRE THANJAVUR DISTRICT YEAR-2018 2 INDEX S. No. Department Page No. 1 State Disaster Management Department, Chennai 1 2. Emergency Toll free Telephone Numbers 1 3. Indian Meteorological Research Centre 2 4. National Disaster Rescue Team, Arakonam 2 5. Aavin 2 6. Telephone Operator, District Collectorate 2 7. Office,ThanjavurRevenue Department 3 8. PWD ( Buildings and Maintenance) 5 9. Cooperative Department 5 10. Treasury Department 7 11. Police Department 10 12. Fire & Rescue Department 13 13. District Rural Development 14 14. Panchayat 17 15. Town Panchayat 18 16. Public Works Department 19 17. Highways Department 25 18. Agriculture Department 26 19. Animal Husbandry Department 28 20. Tamilnadu Civil Supplies Corporation 29 21. Education Department 29 22. Health and Medical Department 31 23. TNSTC 33 24. TNEB 34 25. Fisheries 35 26. Forest Department 38 27. TWAD 38 28. Horticulture 39 29. Statisticts 40 30. NGO’s 40 31. First Responders for Vulnerable Areas 44 1 Telephone Number Officer’s Details Office Telephone & Mobile District Disaster Management Agency - Thanjavur Flood Control Room 1077 04362- 230121 State Disaster Management Agency – Chennai - 5 Additional Cheif Secretary & Commissioner 044-28523299 9445000444 of Revenue Administration, Chennai -5 044-28414513, Disaster Management, Chennai 044-1070 Control Room 044-28414512 Emergency Toll Free Numbers Disaster Rescue, 1077 District Collector Office, Thanjavur Child Line 1098 Police 100 Fire & Rescue Department 101 Medical Helpline 104 Ambulance 108 Women’s Helpline 1091 National Highways Emergency Help 1033 Old Age People Helpline 1253 Coastal Security 1718 Blood Bank 1910 Eye Donation 1919 Railway Helpline 1512 AIDS Helpline 1097 2 Meteorological Research Centre S. -

(CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11A Designated Location Identity

ANNEXURE 5.11 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11A Designated location identity List of applications for transposition of entry in electoral roll Received in Revision identity (where applications have been Form - 8A received) Constituency (Assembly /£Parliamentary): Shozhinganallur 1. List number@ 2. Period of receipt of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 01/11/2020 01/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial Date of Details of applicant Details of person whose entry is to be transposed Present place of Date/Time of number of receipt (As given in Part V ordinary residence hearing* application of Form 8A) Name of person Part/Serial EPIC NO. whose entry is to be no. of roll in transposed which name is included 1 01/11/2020 Vignesh Vignesh 238 / 601 NFS1333152 5/9 ,Pillaiyar kovil street ,Medavakkam ,Medavakkam , 2 01/11/2020 Panneerselvam Panneerselvam 239 / 516 MZY5450499 5/9 ,Pillaiyar kovil street ,Medavakkam ,Medavakkam , £ In case of Union Territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu & Kashmir @ For this revision for this designated location Date of exhibition at designated Date of exhibition at Electoral * Place, time and date of hearing as fixed by electoral registration officer location under rule 15(b) Registration Officer¶s Office under § Running serial number is to be maintained for each revision for each rule 16(b) designated location 17/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.11 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 11A Designated location identity List of applications for transposition of entry in electoral roll Received in Revision identity (where applications have been Form - 8A received) Constituency (Assembly /£Parliamentary): Shozhinganallur 1. -

Awards and Recognitions

S.No Name Dated On Name of Award Venue National / International HONORED MEMBER OF THE HUB OF PRESTIGIOUS 1 Dr. Senthilkumar Sivanesan 03-04-2018 MSTF, Iran International MUSTAFA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOUNDATION (MSTF) 2 Dr. Vijayalakshmi.S 25-02-2019 SPECIAL RECOGNITION AWARD Saveetha Medical College National Sri Ramachandra Medical College & 3 Dr. Archana. R 09-09-2018 BEST POSTER National Research Institution 4 Dr. Archana. R 05-03-2019 BEST COMMITTEE FOR SAVEETHA RESEARCH CELL Saveetha Medical College, Chennai National 5 Kannan R 02-11-2007 EXSA SILVER AWARD SINGAPORE Singapore International Saveetha Medical College & 6 Lal Devayani Vasudevan 18-11-2016 DR.CV.RAMAN AWARD FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH National Hospital, Thandalam 7 Sudarshan 07-04-2016 CERTIFICATE OF APPRECIATION Saveetha Medical College Chennai National 8 Shoba K 28-04-2019 BEST POSTER Sri Ramachandra Medical College National 9 Shoba K 25-02-2019 DISTINGUISHED FACULTY Saveetha Medical College National Saveetha Medical College & 10 Narasimhalu C R V 18-11-2014 RESEARCH ARTICLE National Hospital, Thandalam Saveetha Medical College & 11 Narasimhalu C R V 13-11-2018 ANNUAL DEPARTMENT RANKING 2018 National Hospital, Thandalam Saveetha Medical College & 12 Narasimhalu C R V 03-11-2017 CERTIFICATE OF APPRECIATION National Hospital, Thandalam 13 Rajendran 07-04-2016 SERVICE APPRECIATION Saveetha Medical College National 14 Dr. Abraham Sam Rajan 07-04-2016 CERTIFICATE OF APPRECIATION Saveetha Medical College National Meenakshi Academy Of Higher 15 Dr. Sridevi 13-12-2013 BEST POSTER National Education And Research 16 Dr. Sridevi 27-09-2017 CERTIFICATE OF ACHIEVEMENT Saveetha Medical College National Saveetha Research Cell, Saveetha 17 Dr. -

Psyphil Celebrity Blog Covering All Uncovered Things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies List New Films List Latest Tamil Movie List Filmography

Psyphil Celebrity Blog covering all uncovered things..!! Vijay Tamil Movies list new films list latest Tamil movie list filmography Name: Vijay Date of Birth: June 22, 1974 Height: 5’7″ First movie: Naalaya Theerpu, 1992 Vijay all Tamil Movies list Movie Y Movie Name Movie Director Movies Cast e ar Naalaya 1992 S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sridevi, Keerthana Theerpu Vijay, Vijaykanth, 1993 Sendhoorapandi S.A.Chandrasekar Manorama, Yuvarani Vijay, Swathi, Sivakumar, 1994 Deva S. A. Chandrasekhar Manivannan, Manorama Vijay, Vijayakumar, - Rasigan S.A.Chandrasekhar Sanghavi Rajavin 1995 Janaki Soundar Vijay, Ajith, Indraja Parvaiyile - Vishnu S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Sanghavi - Chandralekha Nambirajan Vijay, Vanitha Vijaykumar Coimbatore 1996 C.Ranganathan Vijay, Sanghavi Maaple Poove - Vikraman Vijay, Sangeetha Unakkaga - Vasantha Vaasal M.R Vijay, Swathi Maanbumigu - S.A.Chandrasekar Vijay, Keerthana Maanavan - Selva A. Venkatesan Vijay, Swathi Kaalamellam Vijay, Dimple, R. 1997 R. Sundarrajan Kaathiruppen Sundarrajan Vijay, Raghuvaran, - Love Today Balasekaran Suvalakshmi, Manthra Joseph Vijay, Sivaji - Once More S. A. Chandrasekhar Ganesan,Simran Bagga, Manivannan Vijay, Simran, Surya, Kausalya, - Nerrukku Ner Vasanth Raghuvaran, Vivek, Prakash Raj Kadhalukku Vijay, Shalini, Sivakumar, - Fazil Mariyadhai Manivannan, Dhamu Ninaithen Vijay, Devayani, Rambha, 1998 K.Selva Bharathy Vandhai Manivannan, Charlie - Priyamudan - Vijay, Kausalya - Nilaave Vaa A.Venkatesan Vijay, Suvalakshmi Thulladha Vijay 1999 Manamum Ezhil Simran Thullum Endrendrum - Manoj Bhatnagar Vijay, Rambha Kadhal - Nenjinile S.A.Chandrasekaran Vijay, Ishaa Koppikar Vijay, Rambha, Monicka, - Minsara Kanna K.S. Ravikumar Khushboo Vijay, Dhamu, Charlie, Kannukkul 2000 Fazil Raghuvaran, Shalini, Nilavu Srividhya Vijay, Jyothika, Nizhalgal - Khushi SJ Suryah Ravi, Vivek - Priyamaanavale K.Selvabharathy Vijay, Simran Vijay, Devayani, Surya, 2001 Friends Siddique Abhinyashree, Ramesh Khanna Vijay, Bhumika Chawla, - Badri P.A. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Advance Tour Programme for Division Fever Camps 17.04.2021

Advance Tour Programme for Division Fever Camps 17.04.2021 FIRST CAMP LOCATION SECOND CAMP LOCATION THIRD CAMP LOCATION SNO ZONE DIVISION MO POSTED 8.30 AM TO 11 AM 11.30 AM TO 1.30 PM 4.00 AM TO 7.00 PM 1 4 Magaliamman Kovil street , Ernavoor , Perumal kovil street , Ernavoor , Chennai Dr.Prasath 2 2 Thilagar Nagar , Ennore , Chennai 57 Kamraj Nagar , , Ennore , Chennai 57 Dr.Arun Vivekanandar 3 11 Kailash Sector , Thiruvottiyur , Chennai 19 Janakiyammal Estate , Thiruvottiyur , Dr.Arunya Thiruvottiyur 4 12 & 13 Sathangadu High Road , ( Near St.Paul's School Ayyapillaithottam 2nd Street , Dr.Vijiyalakshmi 5 9 Thiruvottiyur High road , Thiruvottiyur , Pattinathar Kovil street , , Thiruvottiyur , Dr.Vinodh 6 8 Masthan kovil Street , Thiruvottiyur Dr.Saranyavathi 7 19 1st Main road , Mathur, Manali 3rd main road, Mathur, Manali . Dr.Benith Manali 8 18 Thillaipuram, Manali Div.20. New MGR Nagar, Manali Dr. Elumalai 9 22 GANDHI MAIN STREET DR. RAMESH RAJA 10 24 SIVA PRAKASAM NAGAR DR. RAMESH RAJA 11 25 KATTIDA THOLLILALAR NAGAR DR. CHRISTINA 12 26 THIRUMALAI NAGAR SASTHRI NAGAR 1. DR. MADUBALA 13 27 IDAIMA NAGAR DR. PRAVEEN KUMAR 14 Madhavaram 28 ARINGAR ANNA STREET DR. NIRMAL KUMAR 15 29 DEVARAJAN STREET DR. SATHYA DEVI 16 30 KAMARAJ STREET DR. PAUL JAISON 17 31 MUTHUMARIAMMAN KOIL STREET DR. ACHINA TITUS 18 32 SARATHY NAGAR 1ST STREET DR. VIDHYA 19 33 KAMARAJ SALAI DR. MYTHILI 20 34 R V NAGAR SOLAIAMMAN KOIL STREET DR. STEPHEN 21 35 T H ROAD CHINNADIMADAM MUTHAMIL NAGAR 7TH BLOCK ICDS Dr.Mathina, 22 36 MKB NAGAR BUS DEPO INDUSTRIAL ESTATE Dr.Thahaseen 23 37 MULLAI COMPLEX VALLUVAR STREET Dr.Joseph 24 38 NETHAJI NAGAR MAIN ROAD NETHAJI NAGAR 5TH ST Dr.Karan 25 39 A E SCHEME ROAD NAGOORAR THOTTAM Dr.Thirumalai raj 26 40 CORPORATION COLONY T SUNAMI QUATETRS Dr.kalaiyarasi 27 Tondiarpet 41 ANNA NAGAR DEVIKARUMARIAMMAN NAGAR DR.Zoharath 28 42 T H ROAD MAIN ST THILAGAR NAGAR COMMUNITY HALL DR. -

Copy of Brochure

S A T H Y A B A M A INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY (Deemed to be University) SCHOOL OF BIO & CHEMICAL ENGINEERING THE CENTER FOR MOLECULAR DATA SCIENCE & C O N T A C T U S SYSTEMS The placement record of our students The Center for Molecular Data Science & Systems Biology(CMDSSB), Sathyabama Institute of Science & Technology, BIOLOGY Placement & Rajiv Gandhi salai, Jeppiaar Nagar, Chennai- 600 119 Higher studies Admissions officer - 044 24503150/51/52/54/55 CMDSSB - 044 24503245/ 9840235781/ 9444963185 ABOUT THE CENTRE HIGHLIGHTS In the long term vision of our honorable chancellor, the Purpose-driven faculty Department of Bioinformatics at the Sathyabama Highly qualified faculty regularly publish their research in Institute of Science and Technology had its inception in peer-reviewed journals nationally and internationally August 2001 and it is currently upgraded and re - besides offering consultancy services to various christened as the Center for Molecular Data Science and institutions and organizations throughout the city. Systems Biology (CMDSSB).The centre boasts of a plethora of commercial and open source software and the best of hardware infrastructure that are housed in Real-time learning spacious and well – maintained computational With special emphasis on interdisciplinary learning the laboratories. centre focuses on cutting edge research using case studies and simulations backed up by experimental PROGRAMS OFFERED techniques for structured data analytics. ▪ Bachelor of Science in Bioinformatics & Data Science ▪ Master of Science in Bioinformatics & Data Science Bridging the gap ▪ Ph. D in Bioinformatics The centre constantly remains in touch with industry ▪ Post Doctoral Fellowship in Bioinformatics sector to understand their needs, so as to bridge the gap between the academia and industry, exhorting student ADJUNCT FACULTY Our center has adjunct faculty of international and initiative, research exposure, hands on training and national repute from – placement. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

Admission to MDS Degree Course Offered in Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Affiliated to the Tamil Nadu Dr

Accredited by NAAC with ‘A’ Grade Admission to M.D.S. Degree Course - (Academic year 2020-21) Information bulletin for candidates who applied for Dental common counseling conducted by Directorate of Medical Education (Secretary Selection Committee, Kilpauk) for Admission to MDS Degree Course offered in Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Affiliated to The Tamil Nadu Dr. MGR Medical University, Guindy, Chennai and Dental Council of India, New Delhi. About the Institution: Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute (CDCRI): Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute (CDCRI) is a recognized Dental institution affiliated to The Tamil Nadu Dr. MGR Medical University. The Institution offers BDS & MDS courses having well qualified and dedicated faculty members. CDCRI also boasts of state of the art infrastructural facilities, renders dental care of international standard and promotes various research and development activities leading to large number of publications and patents. The Institution is a NAAC accredited institution with ‘A’ Grade. Infrastructure: Chettinad Dental College & Research Institute - Information bulletin for M.D.S. Degree Course 2020-21 Page 1 The campus is pollution free with green zones, battery operated vehicles and bi-cycles to commute within the large campus. The entire campus is wi-fi enabled to provide access for the students to enhance their learning. Entire campus is monitored with Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) for safety and security purposes. Institution promotes research and development. The students have received scholarships from various national research agencies like ICMR etc. Chettinad Dental College & Research Institute - Information bulletin for M.D.S. Degree Course 2020-21 Page 2 Lecture Halls: Gallery type AC Lecture halls are fully equipped with modern gadgets and enabled with multimedia. -

Study Report on Gaja Cyclone 2018 Study Report on Gaja Cyclone 2018

Study Report on Gaja Cyclone 2018 Study Report on Gaja Cyclone 2018 A publication of: National Disaster Management Authority Ministry of Home Affairs Government of India NDMA Bhawan A-1, Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi - 110029 September 2019 Study Report on Gaja Cyclone 2018 National Disaster Management Authority Ministry of Home Affairs Government of India Table of Content Sl No. Subject Page Number Foreword vii Acknowledgement ix Executive Summary xi Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Cyclone Gaja 13 Chapter 3 Preparedness 19 Chapter 4 Impact of the Cyclone Gaja 33 Chapter 5 Response 37 Chapter 6 Analysis of Cyclone Gaja 43 Chapter 7 Best Practices 51 Chapter 8 Lessons Learnt & Recommendations 55 References 59 jk"Vªh; vkink izca/u izkf/dj.k National Disaster Management Authority Hkkjr ljdkj Government of India FOREWORD In India, tropical cyclones are one of the common hydro-meteorological hazards. Owing to its long coastline, high density of population and large number of urban centers along the coast, tropical cyclones over the time are having a greater impact on the community and damage the infrastructure. Secondly, the climate change is warming up oceans to increase both the intensity and frequency of cyclones. Hence, it is important to garner all the information and critically assess the impact and manangement of the cyclones. Cyclone Gaja was one of the major cyclones to hit the Tamil Nadu coast in November 2018. It lfeft a devastating tale of destruction on the cyclone path damaging houses, critical infrastructure for essential services, uprooting trees, affecting livelihoods etc in its trail. However, the loss of life was limited. -

![208] Chennai, Saturday, May 23, 2020 Vaikasi 10, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1879/208-chennai-saturday-may-23-2020-vaikasi-10-saarvari-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2051-721879.webp)

208] Chennai, Saturday, May 23, 2020 Vaikasi 10, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2020 [Price: Rs. 11.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 208] CHENNAI, Saturday, may 23, 2020 Vaikasi 10, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a Section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFicationS BY GOVERNMENT REVENUE AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT Department COVID-19 – INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL – EXTENDING RESTRICTIONS IN THE territorial JURISDICTIONS OF THE State OF TAMIL NADU. [G.O. (Ms.) No. 247, Revenue and Disaster Management (DM-II), 23rd May 2020, ¬õè£C 10, ꣘õK, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´-2051.] No. II(2)/REVDM/348(L-1)/2020. WHEREAS in the reference third and fourth read above, the Government have extended the State-wide lockdown from 00:00 hrs of 17-5-2020 till 24:00 hrs of 31-5-2020 under the Disaster Management Act, 2005 with various relaxations ordered in G.O.Ms.No.217, Revenue and Disaster Management (DM-II) Department, dated 3-5-2020 and amendments issued thereon with State specific existing restrictions and new relaxations. WHEREAS the Public and auto rickshaws Drivers associations have requested the Government to permit auto rickshaws for movement of persons. NOW THEREFORE the Government issue the following amendment to G.O.Ms.No.245, Revenue & Disaster Management (DM-II) Department, dated 18-5-2020: A) the sub-clause "Taxi and auto rickshaws are permitted for urgent medical treatment with TN e-pass within the District, in respect of 12 Districts where Intra District movements are otherwise not permitted" under Clause V shall be replaced as "Taxi are permitted for urgent medical treatment with TN e-pass within the District, in respect of 12 Districts where Intra District movements are otherwise not permitted.