Case Study Series13 April 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenya Election History 1963-2013

KENYA ELECTION HISTORY 1963-2013 1963 Kenya Election History 1963 1963: THE PRE-INDEPENDENCE ELECTIONS These were the last elections in pre-independent Kenya and the key players were two political parties, KANU and KADU. KADU drew its support from smaller, less urbanized communities hence advocated majimboism (regionalism) as a means of protecting them. KANU had been forced to accept KADU’s proposal to incorporate a majimbo system of government after being pressured by the British government. Though KANU agreed to majimbo, it vowed to undo it after gaining political power. The majimbo constitution that was introduced in 1962 provided for a two-chamber national legislature consisting of an upper (Senate) and lower (House of Representative). The Campaign KADU allied with the African People’s Party (APP) in the campaign. KANU and APP agreed not to field candidates in seats where the other stood a better chance. The Voting Elections were marked by high voter turnout and were held in three phases. They were widely boycotted in the North Eastern Province. Violence was reported in various parts of the country; four were killed in Isiolo, teargas used in Nyanza and Nakuru, clashes between supporters in Machakos, Mombasa, Nairobi and Kitale. In the House of Representative KANU won 66 seats out of 112 and gained working majority from 4 independents and 3 from NPUA, KADU took 47 seats and APP won 8. In the Senate KANU won 19 out 38 seats while KADU won 16 seats, APP won 2 and NPUA only 1. REFERENCE: NATIONAL ELECTIONS DATA BOOK By Institute for Education in Democracy (published in 1997). -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Transition and Reform People’S Peacemaking Perspectives on Kenya’S Post-2008 Political Crisis and Lessons for the Future

REPORT Transition and reform People’s Peacemaking Perspectives on Kenya’s post-2008 political crisis and lessons for the future James Ndung’u and Manasseh Wepundi March 2012 SUDAN Turkana ETHIOPIA Lake Turkana Mandera Marsabit a UGANDA Wajir West Pokot Samburu Isiolo Trans Elgeyo SOMALIA Nzoiaa Marakwet Baringo Bungoma d Uasihin Gishud Busia Kakamega Laikipia Nandi Meru Siaya Vihiga Kisumu d Nyandarua L. Victoria d Tharaka Kerichod d Garissa Nakuru Homa Kirinyaga Bay Nyamira d Embu Kisii Bomet Muranga Migoria d Narok Nairobi d Machakos Kitui Tana River Kajiado Makueni Lamu ³ TANZANIA Kilifi Legend Taita d Hotspots Taveta Indian Ocean a Potential hotspots Mombasa International boundary Kwale a County boundary Shoreline SCALE: 1:4,500,000 Ocean/lakes 075 150 300 Km Prepared by Kenya National Bureau of Statistics_GIS Unit-2009 Census This map is not an authority on delineation of boundaries Transition and reform People’s Peacemaking Perspectives on Kenya’s post-2008 political crisis and lessons for the future James Ndung’u and Manasseh Wepundi SAFERWORLD MARCH 2012 Acknowledgements This report was written by James Ndung’u and Manasseh Wepundi. We wish to thank a number of interviewees and focus group participants for their views and feedback. They include staff from Konrad Adeneur Stiftung, Africa Centre for Open Governance, Movement for Political Accountability, Peace and Development Network Kenya and community representatives from Western, Eastern, Rift Valley, Nyanza, Nairobi, Coast, North Eastern and Central Provinces who participated in focus group discussions. Thanks also go to Bonita Ayuko of Saferworld for organising focus groups and consultative forums in the provinces. -

Project Proponent and Sponsor ENVIRONMENTAL and SOCIAL

Project Proponent and Sponsor PROJECT MODEL: BUILD OPERATE TRANSFER (BOT) ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED NAIROBI EXPRESSWAY PROJECT VOLUME I Date: January, 2020 Report Prepared by; Nairobi Expressway ESIA TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRM OF EXPERTS: I SPONSOR AND PROPONENT: I TABLE OF CONTENTS II LIST OF FIGURES IX LIST OF TABLES IX LIST OF CAPTIONS XI ACRONYMS XI ABBREVIATIONS XII 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XIII 1.1 OVERVIEW XIII 1.2 BACKGROUND TO THE PROJECT XIII 1.3 PROPOSED EXPRESSWAY DESIGN XIV 1.4 ESIA PROCESS OR METHODOLOGY XIV 1.4.1 DOCUMENT REVIEW XIV 1.4.2 SITE VISITS XIV 1.4.3 IMPACT ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY XV 1.4.4 ESIA PROJECT REPORT OBJECTIVES XV 1.4.5 POTENTIAL IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES XVIII 1.4.6 ANALYSIS OF IMPACTS XVIII 1.5 RECOMMENDATIONS XX 2 INTRODUCTION & CONTEXT 1 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT 1 2.2 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1 2.3 PREVIOUS ESIA STUDIES ON THE CORRIDOR: 1 2.4 PROJECT PROPONENT 2 1.5.2 PROJECTS ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL CONSULTANTS 2 2.5 REPORT STRUCTURE 3 2.6 LIMITATIONS OF THIS REPORT 4 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 5 3.1 PAST INITIATIVES ON THE SECTION JKIA - RIRONI 5 CBRC Centric Africa Limited. Page ii Nairobi Expressway ESIA 3.2 SUBSTANTIATION OF THE PROJECT 5 3.3 KEY DESIGN SOLUTIONS 6 3.3.1 GENERAL INFORMATION 6 3.4 ALIGNMENT SCHEME 6 3.4.1 KEY TECHNICAL DATA 9 3.4.2 ROW EARTHWORKS, DRAINAGE AND DIVERSION ACTIVITES 9 3.5 DRAINAGE DESIGN 13 3.5.1 SCHEME 1: INTRODUCE THE ROADBED WATER INTO THE DRAIN DITCHES ON BOTH SIDES OF A8 ROAD; 14 3.5.2 SCHEME 2: BUILD NEW OUTSIDE DRAIN DITCHES (CANALS) ON BOTH SIDES OF A8, AND FINALLY DIVERT INTO NATURAL RIVERS 14 3.5.3 SCHEME 3: ALL WATER OUTLETS ARE CONNECTED VIA CONCEALED WATER PIPES AND FINALLY LEAD TO NAIROBI RIVER. -

AREA: PART of DAGORETTI ROAD AREA: TASSIA ESTATE DATE: Tuesday 07.02.2017 TIME: 9.00 A.M

AREA: PART OF DAGORETTI ROAD AREA: TASSIA ESTATE DATE: Tuesday 07.02.2017 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. DATE: Monday 06.02.2017 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. Part of Dagoretti Rd, Karinde, Karen Bible College, African NCPB Silos, Tumaini Estate, Avenue 1 & 2, Tassia Est, Kobil, International Univ, Rhino Park, Resurrection Garden & adjacent Part of Outer Ring Road & adjacent customers. customers. MACHAKOS COUNTY AREA: PART OF NGONG’ ROAD, RIARA ROAD AREA: WHOLE OF EPZ SUBSTATION DATE: Wednesday 08.02.2017 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. DATE: Sunday 05.02.2017 TIME: 8.00 A.M – 5.00 P.M. Makueni Rd, Suguta Rd, Mazeras Rd, Oloitoktok Rd, Mararo Avenue, Oleodume Rd, Riara Rd, Kenya Science, Part of Ngong’ Rd, Makindi Whole of Kitengela Town, Isinya, Kajiado Town, Ilbissil, Rd & adjacent customers. Namanga Town, APEX (RMD), Whole of EPZ, Prime Steel Ltd, Milimani Est, Air View Est, Kitengela Prisons, Kenya Kids, AREA: KIBERA, CHINA CENTRE Vekaria Indus, Marble & Granite, Excel Girls Sch, New Valley, Safaricom, Cornation Flowers, Hon. Saitoti Home, Ostrich DATE: Wednesday 08.02.2017 TIME: 9.00 A.M. – 5.00 P.M. NAIROBI NORTH REGION Farm, Cham Flowers, Pj Dave, Kenchic Kisaju, Isinya Town, Nairobi Baptist Church, Jamii Autocare, WOFAK, Beam Hearing NAIROBI COUNTY Kenchic Kiwanja, Notresh Water Kaptei, Hon. Nkaiserry, Maua Centre, Baywater Court, Faulu Kenya, Kay Group Centre, Central Agri Tech, Sigma Flower & adjacent customers. AREA: EASTLANDS, JUJA ROAD Nazarene Church, Part of Coptic Church, Caremax, Part of Ngong’ DATE: Sunday 05.02.2017 TIME: 8.00 A.M. -

Plastic Primary Industrial Packaging Clearance Register

PLASTIC PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PACKAGING CLEARANCE REGISTER NO APPLICANTS ADDRESS CATEGORY PRODUCT CATEGORY 1. PRIMA PLASTICS BOX 5626, NAIROBI USE PACKAGING OF PEOPLE DAILY INDUSTRIES LTD NEWSPAPERS 2. ALPHA FINE FOODS LTD BOX 10338-00100, USE PACKAGING OF MEAT & VEGETABLE NAIROBI PRODUCTS 3. FLAMINGO BOX 10222-00400, USE PACKAGING OF FLOWERS FOR EXPORT HORTICULTURE (K) LTD NAIROBI 4. SUN FLORITECH LIMITED BOX 1701-20117, USE PACKAGING OF FLOWERS FOR EXPORT NAIVASHA 5. UNGA FARM CARE (EA) BOX 41788-00100, USE FLOUR PACKAGING LTD NAIROBI 6. GOLDEN TULIP FARMS LTD BOX 107-20303, OL USE FLOWER EXPORT PACKAGING KALOU 7. FINLAYS BRUSHWARE LTD BOX 32039-00600, MANUFACTURE PACKAGING FOR COPPER CABLES, PAINT NAIROBI BRUSHES AND RUBBER PRODUCTS 8. VESTERGAARD FRANDSEN BOX 66889-00800 USE IMPORTED MOSQUITO NETS & WATER (EA) LTD PURIFIERS 9. KENCHIC LTD BOX 20052-00200 USE FOR PROCESSED CHICKEN PACKAGING 10. PATCO INDUSTRIES LTD BOX 44100-00100 MANUFACTURE PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PACKAGING OF SWEETS 11. BINS (NAIROBI) SERVICES BOX 42766-00100 USE GARBAGE BIN LINERS LIMITED 12. HOUSE OF WAINE BOX 25035-00623 USE GARBAGE BIN LINERS 13. NOVA INDUSTRIES BOX 18510-00500 USE PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PACKAGING OF LIMITED PESTICIDES, ,INSECTICIDES AND FUNGICIDES 14. GALAIYA FOODS KENYA BOX 43293-00100, USE PACKAGING OF VARIOUS FOODSTUFFS LTD NAIROBI E.G. SPICES & DATES 15. CASSINI AND TONOLO LTD BOX 14325-00800 IMPORTATION PCE PACKAGES SPARE PARTS FROM NAIROBI MANUFACTURERS 16. MUTHAIGA FINE MEAT BOX 63204-00619, USE PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PACKAGING OF LTD NAIROBI MEAT PRODUCTS 17. MASTER MIND BOX 68144-00200, USE PACKING SAMPLES FOR EXPORT TOBACCO(K) LTD NAIROBI 18. CLASSIC POLO D’ZINER BOX 48287 NAIROBI IMPORTATION & PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PACKAGING OF COLLECTIONS LTD USE GARMENTS 19. -

Kitengela Urban Development Trends in 2015 ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1:100,000 KITENGELA URBAN DEVELOPMENT TRENDS IN 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 36°48'0"E 36°51'0"E 36°54'0"E 36°57'0"E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Nairobi SYOKIMAU ! To ! MLOLONGO ! ! LEMELEPO ! ! h ! ac ! n Mb ! ! ST MARKS ACADEMY-PRI ! ! E m ka h ba ! 1°24'0"S c si 1°24'0"S ! b a ! M NAIROBI NATIONAL PARK To Mombasa ! ! ! P ! ip ! ko e h o lin ! c ak e ! a ! b Em M ! ! ! ! ! ! NGELANI ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MELANIE JUNIOR ACADEMY-PRI io ! ! p ! ! n Ka ! ! ! m ! o b ! o ! o tot a ok u a ! k g r a N ! ! Em ! ! ! ! ! ! ! To Mombasa ! ! ! ! ATHI RIVER NORTH ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! SHOLINKE i ! ! A th ! ! ! ! la ! ATHI RIVER ! e g ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! ! ! e ! ! ! ! t ! ! i ! ! ! K ! ! ! ! ! 1°27'0"S ! 1°27'0"S ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ingela Supata ! ! ! ! n Bright Hill ! g ! ! ! ! n ! a ! o el n Sch p g Noonkopir Township Pri ! ! o ! n ! EPZ ! ! p ite K r ! ! o ir n ! o v ! ! o r # k Kitengela Medical ! ! ! N n o Kitengela Police stn ! ! N ! Services ! ! ! ! ! ! Athi River Prison Dispensary v® ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! ! ! Athi River GK Prison ! ! v® # ! ! ! ! ! ! KITENGELA ! ! ! ! Kitengela Boarding pri ! ! ! ! ! ! P ! ! n irr I OLOOSIRIKON rv ! ! o ! k ! n H ! o ! N ! S ! ! ! ! Milimani Kitengela Jnr Academy ! Green Valley N ! ! High ! Voltage Po ! Estate ! ! wer T ! r W ! ansm n ! ! ission ! ! ! ! ! # ! ! O ! ! ! ! T ! ! ! ! Fountain Estate ! R ! ! # ! E ! la ! ! e ! V 1°30'0"S ! 1°30'0"S ! g I ! ! n ! R ! e ! t Orchard -

Machakos County

SUMMARY OF INSTALLATION OF DEVICES IN PUBLIC PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN MACHAKOS COUNTY SUB-COUNTY ZONE SCHOOL LDD TDD PROJECTOR DCSWR MACHAKOS MUVULI MACHAKOS 202 2 1 1 MATUNGULU KIANZABE KATHEKA 44 2 1 1 MASINGA KIVAA KIVAA 44 2 1 1 KATHIANI IVETI ISOONI 83 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER MLOLONGO 107 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI/KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI 62 2 1 1 KALAMA KALAMA KALAMA 30 2 1 1 MASINGA EKALAKALA NZUKINI 55 2 1 1 MATUNGULU KIANZABE KITHUIANI 83 2 1 1 MWALA KATHAMA MISELENI 56 2 1 1 YATTA IKOMBE KYASIONI 69 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER DAYSTAR MULANDI 22 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER KAMULU D.E.B 15 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER KWAMBOO 25 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER NGELANI RANCH 28 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER OLOSHAIKI 17 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER SEME 15 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER KAVOMBONI 9 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER ATHI RIVER KASUITU 23 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA KYUMBI 46 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA KALIMANI 32 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA KWA KALUSYA 26 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA MATHATANI 18 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA MAUTAIN VIEW 25 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA MITATINI 15 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA MUTHWANI 30 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA NDOVOINI 29 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA NG'ALALYA 28 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA ST. FRANCIS OF ASSIS 22 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA WATHIA 15 2 1 1 ATHI RIVER LUKENYA IVALINI 34 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI/KANGUNDO KILINDILONI 25 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI/KANGUNDO KIOMO 32 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI/KANGUNDO KWAKATHULE 48 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI/KANGUNDO KITHUNTHI S.A 23 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KAKUYUNI/KANGUNDO KWAMWENZE 23 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO ITUUSYA 32 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KAMUTONGA 10 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KIKAMBUANI 39 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KWAMWILILE 33 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KWANDIU 33 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KYAAKA 21 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KYAI A.I.C 30 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO KYELENDU 22 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO MALATANI 15 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO MATETANI 29 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO MBILINI 22 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO MBONDONI 29 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO MIKOIKONI 35 2 1 1 KANGUNDO KANGUNDO ST. -

Eia 1842 Indesign Makumbi Esia Report

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT AT L.R. No.7149/138 IN SYOKIMAU, MACHAKOS COUNTY GPS COORDINATES: -1.38067 & 36.92432 for Latitude and Longitude Respectively APRIL 2021 ESIA Study report for proposed Residential Development Project in Syokimau, Mavoko Sub-county by Indesign Makumbi Limited DECLARATION AND SUBMISSION We the undersigned consultants, on behalf of the proponent, Indesign Makumbi Limited of P.O Box 67961 - 00200, Nairobi, Kenya, submit the following Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Report, for the proposed Residential Development in Syokimau/ Mlolongo area, Mavoko Sub-county in Machakos County. The Environmental and Social Impact Assessment has been carried out according to the Environmental Management and Coordination (Amendments) Act, 2015 and Environmental (Impact Assessment and Audit) Regulations, 2003; Rev. 2018. In undertaking this task, we endeavoured to comply with the legal requirements, institutional frameworks and international best guidelines. The required professional‘s standards and practices were also applied in carrying out the ESIA study. To the best of our knowledge; we declare and submit that all information contained in this ESIA report is an accurate and a truthful representation of the ESIA process of the proposed Residential Development Project as hereupon described. Lead Expert Mr. Moses U. Muisyo Signature ……………………………. NEMA Reg. No 7688 Date…………………………………… Email: [email protected] Cell No: +254 721-171-916 Associate Expert -

EIA 1478 Residential Dev. Syokimau Machakos County

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT (APARTMENTS) AND A SPORTS FACILITY (MAIN BUILDING, SIDE FOOTBALL PITCH AND SWIMMING POOL) ON PLOT L.R NO 12715/556 OFF CHADY ROAD IN SYOKIMAU AREA, MACHAKOS COUNTY PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION SITE LATITUDE: -1.365869° LONGITUDE: 36.921179° This Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Project Report is submitted to Kenya National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) in conformity with the requirements of the Environmental Management and Coordination Act, 1999 and the Environmental (Impact Assessment and Audit) Regulations, 2003. PROPONENT: ZAKAYO WACHIRA GITHAE P.O.BOX 57333-00200 NAIROBI JUNE 2018 DOCUMENT AUTHENTICATION This Environmental Impact Assessment Study report has been prepared by iPlan Consult ( Intl) LTD (NEMA Reg No. 7597) in accordance with the Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) 1999 and the Environmental (Impact Assessment) and Audit regulations 2003 which requires that every development project must have an EIA report prepared for submission to the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA). We the undersigned, certify that the particulars in this report are correct and righteous to the best of our knowledge. EIA/EA LEAD EXPERT: iPlan Consult ( Intl) LTD (NEMA REG NO: 7597) P.O BOX 28634-00100, NAIROBI TEL: 02022251702 / 0203546499 CELL: 0721891005 EMAIL: [email protected], [email protected] Signature…………………………………Date….…...…………………… SHADACK K. MBUTA (NEMA REG. NO 6315) PROPONENT: ZAKAYO WACHIRA GITHAE P.O.BOX -

A Case Study of Mlolongo Township, Machakos

CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE INFLUENCE OF TELEVISION ON SEXUAL BEHAVIOR OF YOUNG WOMEN: A CASE STUDY OF MLOLONGO TOWNSHIP, MACHAKOS COUNTY ^ BY RHOYDAH O.^NYAMBANE K50/77222/2009 The Research Project is Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Award of Master of Arts Degree in Communication Studies of The School of Journalism, University of Nairobi. t November 2011 University of NAIROBI Library \ DECLARATION This project is my original work and has not been presented in part or any other form for the award of a degree in any other university Signed . .......... # 3 .......................... ......Date. m L l / m u ............ Rhoydah O. Nyambane APPROVAL This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as University Supervisor. ^ t Ndeti Ndati Date Lecturer School of Journalism University of Nairobi 11 Acknowledgement First and foremost I would like to thank the Almighty God for giving me an opportunity to pursue this course and so doing enabled me to follow after my dream which at some stage, seemed like it had died. Many thanks to my supervisor Mr. Ndeti Ndati for agreeing to supervise my work. Your wise counsel, guidance and patience throughout the period helped me move faster than I expected. Your quick response to my many questions and promptness in returning the work always left me humbled. God bless you so much. I thank Ms Wairimu Gichohi, for her wise counsel whenever I needed it. Thank you for taking time off your busy schedule to listen, guide and encourage me. And to Mr Hezron Mogambi, thank you for advising me in thd'initial stages of this work that enabled me shape my research topic and forjntroducing me to my supervisor because you had faith l in his competency. -

Annual Report.Cdr

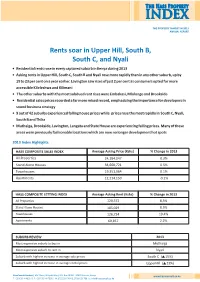

The Hass Property INDEX THE PROPERTY MARKET IN 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Rents soar in Upper Hill, South B, South C, and Nyali • Residential rents rose in every captured suburb in Kenya during 2013 • Asking rents in Upper Hill, South C, South B and Nyali rose more rapidly than in any other suburb, up by 19 to 23 per cent on a year earlier. Lavington saw rises of just 2 per cent as consumers opted for more accessible Kileleshwa and Kilimani • The other suburbs with the most subdued rent rises were Embakasi, Mlolongo and Brookside • Residential sales prices recorded a far more mixed record, emphasizing the importance for developers in sound business strategy • 9 out of 42 suburbs experienced falling house prices while prices rose the most rapidly in South C, Nyali, South B and Thika • Muthaiga, Brookside, Lavington, Langata and State House are experiencing falling prices. Many of these areas were previously fashionable locations which are now no longer development hot spots 2013 Index Highlights HASS COMPOSITE SALES INDEX Average Asking Price (Kshs) % Change in 2013 All Properties 24,184,047 0.3% Stand Alone Houses 34,660,721 0.5% Townhouses 19,351,064 0.1% Apartments 12,214,150 -0.2% HASS COMPOSITE LETTING INDEX Average Asking Rent (Kshs) % Change in 2013 All Properties 120,372 8.5% Stand Alone Houses 185,029 8.5% Townhouses 126,724 19.4% Apartments 69,857 2.2% SUBURB REVIEW 2013 Most expensive suburb to buy in Muthaiga Most expensive suburb to rent in Nyari Suburb with highest increase in average sale prices South C ( 15%) Suburb with highest increase in average rental prices UpperHill ( 23%) HassConsult Limited | ABC Place, Waiyaki Way | P.O.