NIH Public Access Author Manuscript J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutation Analysis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms AHS - M2101

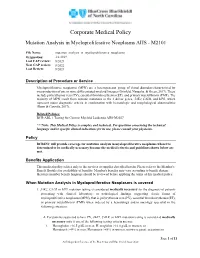

Corporate Medical Policy Mutation Analysis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms AHS - M2101 File Name: mutation_analysis_in_myeloproliferative_neoplasms Origination: 1/1/2019 Last CAP review: 8/2021 Next CAP review: 8/2022 Last Review: 8/2021 Description of Procedure or Service Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are a heterogeneous group of clonal disorders characterized by overproduction of one or more differentiated myeloid lineages (Grinfeld, Nangalia, & Green, 2017). These include polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF). The majority of MPN result from somatic mutations in the 3 driver genes, JAK2, CALR, and MPL, which represent major diagnostic criteria in combination with hematologic and morphological abnormalities (Rumi & Cazzola, 2017). Related Policies: BCR-ABL 1 Testing for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia AHS-M2027 ***Note: This Medical Policy is complex and technical. For questions concerning the technical language and/or specific clinical indications for its use, please consult your physician. Policy BCBSNC will provide coverage for mutation analysis in myeloproliferative neoplasms when it is determined to be medically necessary because the medical criteria and guidelines shown below are met. Benefits Application This medical policy relates only to the services or supplies described herein. Please refer to the Member's Benefit Booklet for availability of benefits. Member's benefits may vary according to benefit design; therefore member benefit language should be reviewed before applying the terms of this medical policy. When Mutation Analysis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms is covered 1. JAK2, CALR or MPL mutation testing is considered medically necessary for the diagnosis of patients presenting with clinical, laboratory, or pathological findings suggesting classic forms of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), that is, polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), or primary myelofibrosis (PMF) when ordered by a hematology and/or oncology specialist in the following situations: A. -

942.Full.Pdf

Original Article Opposite Effect of JAK2 on Insulin-Dependent Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and Akt in Muscle Cells Possible Target to Ameliorate Insulin Resistance Ana C.P. Thirone, Lellean JeBailey, Philip J. Bilan, and Amira Klip Many cytokines increase their receptor affinity for Janus kinases (JAKs). Activated JAK binds to signal transducers and activators of transcription, insulin receptor substrates olypeptides such as erythropoietin, prolactin, (IRSs), and Shc. Intriguingly, insulin acting through its leptin, angiotensin, growth hormone, most inter- own receptor kinase also activates JAK2. However, the leukins, and interferon-␥ bind to receptors that impact of such activation on insulin action remains un- Plack intrinsic kinase activity, recruiting and acti- known. To determine the contribution of JAK2 to insulin vating cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases of the Janus family signaling, we transfected L6 myotubes with siRNA against (JAK) consisting of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and Tyk2 (1–3). JAK2 (siJAK2), reducing JAK2 protein expression by 75%. Activated JAK phosphorylates tyrosine residues within Insulin-dependent phosphorylation of IRS1/2 and Shc was not affected by siJAK2, but insulin-induced phosphoryla- itself and the associated receptor forming high-affinity tion of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) binding sites for a variety of signaling proteins containing Src homology 2 and other phosphotyrosine-binding do- extracellular signal–related kinase, p38, and Jun NH2- terminal kinase and their respective upstream kinases mains, including signal transducers and activators of tran- MKK1/2, MKK3/6, and MKK4/7 was significantly lowered scription, insulin receptor substrates (IRSs), and the when JAK2 was depleted, correlating with a significant adaptor protein Shc (1–4). -

Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines Hepatocyte Growth Factor and Interleukin-11 Are Over-Expressed in Polycythemia Vera and Contribute T

Oncogene (2011) 30, 990–1001 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/11 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anti-inflammatory cytokines hepatocyte growth factor and interleukin-11 are over-expressed in Polycythemia vera and contribute to the growth of clonal erythroblasts independently of JAK2V617F M Boissinot1,3,4, C Cleyrat1,3, M Vilaine1, Y Jacques1, I Corre1 and S Hermouet1,2 1INSERM UMR 892, Institut de Biologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Nantes, France and 2Laboratoire d’He´matologie, Institut de Biologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Nantes, France The V617F activating mutation of janus kinase 2 (JAK2), Keywords: Polycythemia vera; JAK2V617F; hepatocyte a kinase essential for cytokine signalling, characterizes growth factor (HGF); interleukin 11 (IL-11); interleukin Polycythemia vera (PV), one of the myeloproliferative 6 (IL-6); inflammation neoplasms (MPN). However, not all MPNs carry mutations of JAK2, and in JAK2-mutated patients, expression of JAK2V617F does not always result in clone expansion. In the present study, we provide evidence that Introduction inflammation-linked cytokines are required for the growth of JAK2V617F-mutated erythroid progenitors. In a first Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) constitute a series of experiments, we searched for cytokines over- group of three clonal diseases: Polycythemia vera expressed in PV using cytokine antibody (Ab) arrays, and (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET) and primary enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for analyses of myelofibrosis. About half of MPN patients present with serum and bone marrow (BM) plasma, and quantitative activating mutations in the janus kinase 2 (JAK2) gene, reverse transcription–PCRs for analyses of cells purified which encodes for a tyrosine kinase essential for the from PV patients and controls. -

Kinase-Targeted Cancer Therapies: Progress, Challenges and Future Directions Khushwant S

Bhullar et al. Molecular Cancer (2018) 17:48 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0804-2 REVIEW Open Access Kinase-targeted cancer therapies: progress, challenges and future directions Khushwant S. Bhullar1, Naiara Orrego Lagarón2, Eileen M. McGowan3, Indu Parmar4, Amitabh Jha5, Basil P. Hubbard1 and H. P. Vasantha Rupasinghe6,7* Abstract The human genome encodes 538 protein kinases that transfer a γ-phosphate group from ATP to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues. Many of these kinases are associated with human cancer initiation and progression. The recent development of small-molecule kinase inhibitors for the treatment of diverse types of cancer has proven successful in clinical therapy. Significantly, protein kinases are the second most targeted group of drug targets, after the G-protein- coupled receptors. Since the development of the first protein kinase inhibitor, in the early 1980s, 37 kinase inhibitors have received FDA approval for treatment of malignancies such as breast and lung cancer. Furthermore, about 150 kinase-targeted drugs are in clinical phase trials, and many kinase-specific inhibitors are in the preclinical stage of drug development. Nevertheless, many factors confound the clinical efficacy of these molecules. Specific tumor genetics, tumor microenvironment, drug resistance, and pharmacogenomics determine how useful a compound will be in the treatment of a given cancer. This review provides an overview of kinase-targeted drug discovery and development in relation to oncology and highlights the challenges and future potential for kinase-targeted cancer therapies. Keywords: Kinases, Kinase inhibition, Small-molecule drugs, Cancer, Oncology Background Recent advances in our understanding of the fundamen- Kinases are enzymes that transfer a phosphate group to a tal molecular mechanisms underlying cancer cell signaling protein while phosphatases remove a phosphate group have elucidated a crucial role for kinases in the carcino- from protein. -

Novel Transcripts from a Distinct Promoter That Encode the Full-Length

Schmidt et al. BMC Cancer 2014, 14:195 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/195 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Novel transcripts from a distinct promoter that encode the full-length AKT1 in human breast cancer cells Jeffrey W Schmidt1, Barbara L Wehde1, Kazuhito Sakamoto1, Aleata A Triplett1, William W West2 and Kay-Uwe Wagner1,2* Abstract Background: The serine-threonine kinase AKT1 plays essential roles during normal mammary gland development as well as the initiation and progression of breast cancer. AKT1 is generally considered a ubiquitously expressed gene, and its persistent activation is transcriptionally controlled by regulatory elements characteristic of housekeeping gene promoters. We recently identified a novel Akt1 transcript in mice (Akt1m), which is induced by growth factors and their signal transducers of transcription from a previously unknown promoter. The purpose of this study was to examine whether normal and neoplastic human breast epithelial cells express an orthologous AKT1m transcript and whether its expression is deregulated in cancer cells. Methods: Initial sequence analyses were performed using the UCSC Genome Browser and GenBank to assess the potential occurrence of an AKT1m transcript variant in human cells and to identify conserved promoter sequences that are orthologous to the murine Akt1m. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the transcriptional activation of AKT1m in mouse mammary tumors as well as 41 normal and neoplastic human breast epithelial cell lines and selected primary breast cancers. Results: We identified four new AKT1 transcript variants in human breast cancer cells that are orthologous to the murine Akt1m and that encode the full-length kinase. -

Targeting Janus Kinase 2 in Her2/Neu-Expressing Mammary Cancer: Implications for Cancer Prevention Andtherapy

Published OnlineFirst July 28, 2009; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0746 Molecular Biology, Pathobiology, andGenetics Targeting Janus Kinase 2 in Her2/neu-Expressing Mammary Cancer: Implications for Cancer Prevention andTherapy Kazuhito Sakamoto,1 Wan-chi Lin,1 Aleata A. Triplett,1 and Kay-Uwe Wagner1,2 1Eppley Institute for Research in Cancer and Allied Diseases and 2Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska Abstract the Stat5-mediated transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 The Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) is essential for normal mammary promoter (5). Our own studies using Jak2-deficient mammary gland development, but this tyrosine kinase and its main epithelial cells and their isogenic wild-type controls suggest that effector, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, are signaling through this Janus kinase controls not only the also active in a significant subset of human breast cancers. We expression of the cyclin D1 mRNA but, more importantly, Jak2 regulates the accumulation of the cyclin D1 protein in the nucleus have recently reported that Jak2 controls the expression and h nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1. Because this particular D- through modification of the Akt1/GSK3 pathway, which type cyclin has been suggested to be a key mediator for ErbB2- mediates the phosphorylation and nuclear export of cyclin D1 associated mammary tumorigenesis, we deleted Jak2 from (6). The notion that cyclin D1 is a key target of the Jak/Stat pathway is supported by the fact that females deficient in cyclin ErbB2-expressing mammary epithelial cells prior to tumor onset and in neoplastic cells to address whether this tyrosine D1 exhibit impaired mammary gland development similar to Jak2 kinase plays a role in the initiation as well as progression of and Stat5 conditional knockout mice (7, 8). -

Role of the Tyrosine Kinase JAK2 in Signal Transduction by Growth Hormone

Pediatr Nephrol (2000) 14:550–557 © IPNA 2000 REVIEW ARTICLE Christin Carter-Su · Liangyou Rui James Herrington Role of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in signal transduction by growth hormone Received: 15 May 1999 / Revised: 23 December 1999 / Accepted: 2 January 2000 Abstract Chronic renal failure in children results in im- Key words Growth · Growth hormone · JAK2 · Insulin paired body growth. This effect is so severe in some receptor substrates · Signal transducers and activators of children that not only does it have a negative impact on transcription · SH2-B their self-image, but it also affects their ability to carry out normal day-to-day functions. Yet the mechanism by which chronic renal failure causes short stature is not Introduction well understood. Growth hormone (GH) therapy increas- es body height in prepubertal children, suggesting that a As early as 1973 [1], growth hormone (GH) was recog- better understanding of how GH promotes body growth nized as binding to a membrane-bound receptor. Yet the may lead to better insight into the impaired body growth mechanism by which GH binding to its receptor elicits in chronic renal failure and therefore better therapies. the diverse responses to GH remained elusive for several This review discusses what is currently known about more decades. Even cloning of the GH receptor [2] in how GH acts at a cellular level. The review discusses 1987 did not shed light on the mechanism by which the how GH is known to bind to a membrane-bound receptor GH receptor functioned, because the deduced amino acid and activate a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase called Janus sequence of the cloned rabbit and human liver GH recep- kinase (JAK) 2. -

Interpretation of Cytokine Signaling Through the Transcription Factors STAT5A and STAT5B

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW Interpretation of cytokine signaling through the transcription factors STAT5A and STAT5B Lothar Hennighausen1 and Gertraud W. Robinson Laboratory of Genetics and Physiology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA Transcription factors from the family of Signal Trans- the “wrong” STATs and thus acquire inappropriate cues. ducers and Activators of Transcription (STAT) are acti- We propose that mice with mutations in various com- vated by numerous cytokines. Two members of this fam- ponents of the JAK–STAT signaling pathway are living ily, STAT5A and STAT5B (collectively called STAT5), laboratories, which will provide insight into the versa- have gained prominence in that they are activated by a tility of signaling hardware and the adaptability of the wide variety of cytokines such as interleukins, erythro- software. poietin, growth hormone, and prolactin. Furthermore, constitutive STAT5 activation is observed in the major- ity of leukemias and many solid tumors. Inactivation Historical perspective studies in mice as well as human mutations have pro- In 1994, Bernd Groner and colleagues (Wakao et al. vided insight into many of STAT5’s functions. Disrup- 1994), then at the Friedrich Miescher Institute in Basel, tion of cytokine signaling through STAT5 results in a cloned a cDNA from lactating ovine mammary tissue variety of cell-specific effects, ranging from a defective that encoded a transcription factor promoting prolactin- immune system and impaired erythropoiesis, the com- induced transcription of milk protein genes in mammary plete absence of mammary development during preg- epithelium. -

Lung Cancer Biomarkers, Targeted Therapies and Clinical Assays

Review Article on Lung Cancer Diagnostics and Treatments 2015: A Renaissance of Patient Care Lung cancer biomarkers, targeted therapies and clinical assays Jai N. Patel, Jennifer L. Ersek, Edward S. Kim Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, Charlotte, NC, USA Correspondence to: Jai N. Patel, PhD. Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, 1021 Morehead Medical Drive, Charlotte, NC 28203, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Until recently, the majority of genomic cancer research has been in discovery and validation; however, as our knowledge of tumor molecular profiling improves, the idea of genomic application in the clinic becomes increasingly tangible, paralleled with the drug development of newer targeted therapies. A number of profiling methodologies exist to identify biomarkers found within the patient (germ-line DNA) and tumor (somatic DNA). Subsequently, commercially available clinical assays to test for both germ-line and somatic alterations that are prognostic and/or predictive of disease outcome, toxicity or treatment response have significantly increased. This review aims to summarize clinically relevant cancer biomarkers that serve as targets for therapy and their potential relationship to lung cancer. In order to realize the full potential of genomic cancer medicine, it is imperative that clinicians understand these intricate molecular pathways, the therapeutic implication of mutations within these pathways, and the availability of clinical assays to identify such biomarkers. -

Janus Kinases in Leukemia

cancers Review Janus Kinases in Leukemia Juuli Raivola 1, Teemu Haikarainen 1, Bobin George Abraham 1 and Olli Silvennoinen 1,2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Health Technology, Tampere University, 33014 Tampere, Finland; juuli.raivola@tuni.fi (J.R.); teemu.haikarainen@tuni.fi (T.H.); bobin.george.abraham@tuni.fi (B.G.A.) 2 Institute of Biotechnology, Helsinki Institute of Life Science HiLIFE, University of Helsinki, 00014 Helsinki, Finland 3 Fimlab Laboratories, Fimlab, 33520 Tampere, Finland * Correspondence: olli.silvennoinen@tuni.fi Simple Summary: Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) path- way is a crucial cell signaling pathway that drives the development, differentiation, and function of immune cells and has an important role in blood cell formation. Mutations targeting this path- way can lead to overproduction of these cell types, giving rise to various hematological diseases. This review summarizes pathogenic JAK/STAT activation mechanisms and links known mutations and translocations to different leukemia. In addition, the review discusses the current therapeutic approaches used to inhibit constitutive, cytokine-independent activation of the pathway and the prospects of developing more specific potent JAK inhibitors. Abstract: Janus kinases (JAKs) transduce signals from dozens of extracellular cytokines and function as critical regulators of cell growth, differentiation, gene expression, and immune responses. Deregu- lation of JAK/STAT signaling is a central component in several human diseases including various types of leukemia and other malignancies and autoimmune diseases. Different types of leukemia harbor genomic aberrations in all four JAKs (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2), most of which are Citation: Raivola, J.; Haikarainen, T.; activating somatic mutations and less frequently translocations resulting in constitutively active JAK Abraham, B.G.; Silvennoinen, O. -

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Cancer: Breakthrough and Challenges of Targeted Therapy

cancers Review Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Cancer: Breakthrough and Challenges of Targeted Therapy 1,2, 3,4 1 2 3, Charles Pottier * , Margaux Fresnais , Marie Gilon , Guy Jérusalem ,Rémi Longuespée y 1, and Nor Eddine Sounni y 1 Laboratory of Tumor and Development Biology, GIGA-Cancer and GIGA-I3, GIGA-Research, University Hospital of Liège, 4000 Liège, Belgium; [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (N.E.S.) 2 Department of Medical Oncology, University Hospital of Liège, 4000 Liège, Belgium; [email protected] 3 Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacoepidemiology, University Hospital of Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany; [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (R.L.) 4 German Cancer Consortium (DKTK)-German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), 69120 Heidelberg, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Equivalent contribution. y Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 16 March 2020; Published: 20 March 2020 Abstract: Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are key regulatory signaling proteins governing cancer cell growth and metastasis. During the last two decades, several molecules targeting RTKs were used in oncology as a first or second line therapy in different types of cancer. However, their effectiveness is limited by the appearance of resistance or adverse effects. In this review, we summarize the main features of RTKs and their inhibitors (RTKIs), their current use in oncology, and mechanisms of resistance. We also describe the technological advances of artificial intelligence, chemoproteomics, and microfluidics in elaborating powerful strategies that could be used in providing more efficient and selective small molecules inhibitors of RTKs. -

The Role of JAK/STAT Molecular Pathway in Vascular Remodeling Associated with Pulmonary Hypertension

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The Role of JAK/STAT Molecular Pathway in Vascular Remodeling Associated with Pulmonary Hypertension Inés Roger 1,2,*, Javier Milara 1,2,3,*, Paula Montero 2 and Julio Cortijo 1,2,4 1 CIBERES, Health Institute Carlos III, 28029 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] 3 Pharmacy Unit, University General Hospital Consortium of Valencia, 46014 Valencia, Spain 4 Research and Teaching Unit, University General Hospital Consortium, 46014 Valencia, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.R.); [email protected] (J.M.); Tel.: +34-963864631 (I.R.); +34-620231549 (J.M.) Abstract: Pulmonary hypertension is defined as a group of diseases characterized by a progressive increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), which leads to right ventricular failure and prema- ture death. There are multiple clinical manifestations that can be grouped into five different types. Pulmonary artery remodeling is a common feature in pulmonary hypertension (PH) characterized by endothelial dysfunction and smooth muscle pulmonary artery cell proliferation. The current treatments for PH are limited to vasodilatory agents that do not stop the progression of the disease. Therefore, there is a need for new agents that inhibit pulmonary artery remodeling targeting the main genetic, molecular, and cellular processes involved in PH. Chronic inflammation contributes to pulmonary artery remodeling and PH, among other vascular disorders, and many inflammatory mediators signal through the JAK/STAT pathway. Recent evidence indicates that the JAK/STAT Citation: Roger, I.; Milara, J.; pathway is overactivated in the pulmonary arteries of patients with PH of different types.