A Hashtag Worth a Thousand Words

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1034 Policy Manual

Policy Grafton Police Department 1034 Policy Manual Line-of-Duty Deaths 1034.1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE The purpose of this policy is to provide guidance to members of the Grafton Police Department in the event of the death of a member occurring in the line of duty and to direct the Department in providing proper support for the member’s survivors. The Chief of Police may also apply some or all of this policy in situations where members are injured in the line of duty and the injuries are life-threatening. 1034.1.1 DEFINITIONS Definitions related to this policy include: Line-of-duty death - The death of a sworn member during the course of performing law enforcement-related functions while on- or off-duty, or a Civilian member during the course of performing their assigned duties. Survivors - Immediate family members of the deceased member, which can include spouse, children, parents, other next of kin or significant others. The determination of who should be considered a survivor for purposes of this policy should be made on a case-by-case basis given the individual’s relationship with the member and whether the individual was previously designated by the deceased member. 1034.2 POLICY It is the policy of the Grafton Police Department to make appropriate notifications and to provide assistance and support to survivors and coworkers of a member who becomes seriously injured or dies in the line of duty. It is also the policy of this department to respect the requests of the survivors when they conflict with these guidelines, as appropriate. -

'Line of Duty,' Is Unique Cop Show

ARAB TIMES, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 2, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Books ‘A Writer Prepares’ Block’s memoir recalls colorful writing career NEW YORK, June 1, (AP): Lawrence Block has fol- lowed many paths during his long career. “With not a few dead end roads among them,” notes the mystery novelist. Best known for his Matthew Scudder and Bernie Rhodenbarr series, Block has released dozens of pop- ular works through Harper Collins and Dutton among other mainstream publishers. He has received multiple Edgar Awards and Anthony Awards for outstanding fi ction, and his lifetime achievement honors include the Diamond Dagger from the British Crime Writers’ Association and Grand Master status in the Mystery Writers of America. But he has also completed dozens of works under other names, by publishers and publications long since forgotten, and, in some cases, of questionable legality. More recently, he has been publish- ing the books himself, includ- ing “Dead Girl Blues” and the Rhodenbarr novel “The Bur- glar In Short Order,” which both came out in 2020, and his current work, the memoir “A Writer Prepares.” “One big plus of self-pub- lishing is how quickly it can be managed. I can reduce waiting Block time by a minimum of a year if I publish something myself,” he explains. “The downside is not to be shrugged off. Self-pub- lished books rarely get reviewed and hardly ever show up in bookstores. ‘Dead Girl Blues’ didn’t make me This image released by BritBox shows Vicky McClure, (left), and Kelly Macdonald in a scene from the BBC police drama series ‘Line of Duty.’ (AP) rich, and neither will ‘A Writer Prepares.’ But nothing I write is going to do that, no matter who publishes it, and whatever I self-publish stays forever available in electronic and print editions, and probably fi nds what- ever audience it deserves to have.” Television Block is a longtime Greenwich Village resident, fully vaccinated and back outside, enjoying a nice big plate of Brussels sprouts during a recent afternoon in- terview at a favorite cafe. -

Supporting Children and Family Survivors of Police Line-Of-Duty Deaths

Supporting Children and Family Survivors of Police Line-of-Duty Deaths Police Survivors: Line-of-Duty Line-of-Duty Deaths: Deaths Three Essential Points About Children who experience the loss of a parent or other family Children and Family Survivors member through a line-of-duty death are likely to face a 1. Most grief experiences are similar. In most ways, children number of unique issues. School professionals working with and family survivors of line-of-duty deaths experience grief students in such circumstances will be able to provide more and coping with loss much as others do. They have similar effective support when they understand the distinct aspects thoughts, feelings, concerns and needs. of this experience. 2. Some grief experiences are distinct in important ways. The materials in this module are designed as a supplement to Survivors of line-of-duty deaths are coping with unique the broader information at the Coalition’s website. They are issues within a unique culture. Most people outside the law not intended to be a stand-alone resource. enforcement world are unfamiliar with these issues. They were developed collaboratively with the national non- 3. School professionals can make a difference. When school profit organization Concerns of Police Survivors (C.O.P.S.). professionals are aware of the distinct issues facing these C.O.P.S. provides support for families who have experienced families, they can plan and provide more effective support. a line-of-duty death. Over 30,000 families are members of the organization. Take Steps to Make a Difference Are Your Students Affected? To understand more about providing support to survivors of a line-of-duty death, read through the materials in this Each year, more than a hundred law enforcement officers module. -

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue Number

Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin Issue number 220 17 December 2012 1 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 220 17 December 2012 Contents Introduction 4 Standards cases In Breach Line of Duty BBC 2, 17 July 2012, 21:00 and 24 July 2012, 21:00 5 Note to Broadcasters The involvement of people under eighteen in programmes 16 In Breach Paigham-e-Mustafa Noor TV, 3 May 2012, 11:00 18 Rock All Stars Scuzz TV, 19 August 2012, 20:40 32 Islam Channel News The Islam Channel, 8 June 2012, 21:10 43 Good Cop (Trailer) BBC1 HD, 6 August 2012, 18:40 51 Not in Breach The X Factor ITV1, 9 September 2012, 20:00 ITV2, 10 September 2012, 01:05, 10 September 2012, 20:00 and 11 September 2012, 00:15 55 Broadcast Licence Condition cases In Breach Breach of licence conditions Voice of Africa Radio 60 In Breach/Resolved Breach of licence conditions Erewash Sound, Felixstowe Radio, The Super Station Orkney, Seaside FM, Ambur Radio, Phoenix FM 62 2 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 220 17 December 2012 Fairness and Privacy cases Upheld Complaint by Complaint by the Central Electoral Commission of Latvia Russian language referendum item, REN TV Baltic & Mir Baltic, November 2011, various dates and times 66 Complaint by Dr Usama Hasan Islam Channel News, The Islam Channel, 8 June 2012 70 Not Upheld Complaint by Dr Usama Hasan Politics and Media, The Islam Channel, 11 June 2012 77 Other Programmes Not in Breach 89 Complaints Assessed, Not Investigated 90 Investigations List 100 3 Ofcom Broadcast Bulletin, Issue 220 17 December 2012 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content as appear to it best calculated to secure the standards objectives1, Ofcom must include these standards in a code or codes. -

Gender Dynamics in TV Series the Fall: Whose Fall Is It? Adriana Saboviková, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovakia1

Gender Dynamics in TV Series The Fall: Whose fall is it? Adriana Saboviková, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Slovakia1 Abstract This paper examines gender dynamics in the contemporary TV series The Fall (BBC 2013 - 2016). This TV series, through its genre of crime fiction, represents yet another way of introducing a strong female character in today’s postfeminist culture. Gillian Anderson’s Stella Gibson, a Brit and a woman, finds herself in the men’s world of the Police Service in Belfast, where the long shadow of the Troubles is still present. The paper proposes that the answer to the raised question - who the eponymous fall (implied in the name of the series) should be attributed to - might not be that obvious, while also discussing The Fall’s take on feminism embodied in its female lead. Keywords: female detectives, The Fall, TV crime drama, postfeminism Introduction Troubled history is often considered to be the reason for Northern Ireland being described as a nation of borderlines - not only obvious physical ones but also imagined. This stems from the conflict that has been described most commonly in terms of identities - based on culture, religion, and even geography. The conflict that has not yet been completely forgotten as the long shadow of the Troubles (local name, internationally known as the Northern Ireland conflict) is still present in the area. Nolan and Hughes (2017) describe Northern Ireland as “living apart together” separated by physical barriers. These locally called peace walls had to be erected to separate and, at the same time, protect the communities. -

Joplin Police Department 2015 Annual Report

Joplin Police Department 2015 Annual Report The Joplin Police Department is a community funded division of the City of Joplin whose vision is a peaceful and safe community where citizens and visitors experience hometown values and a superior quality of life. Table of Contents Message from Chief Jason Burns…………………………………………..4 City Government and Police Department Supervisors…………5 Vision, Mission, and Values…………………………………………………..6 Multi-Year Plan……………………………………………………………………...7-9 Operations Division……………………………………………………………….10 Patrol Bureau………………………………………………………………………….11-15 S.W.A.T. ………………………………………………………………………..13-14 K9 Unit………………………………………………………………………….15 Special Enforcement Bureau………………………………………………...16-23 Crime Free…………………………………………………………………...16 Traffiic………………………………………………………………………….17 DWI Unit……………………………………………………………………..17 Motorcycles………………………………………………………………...18 HMV………….………………………………………………………………...18 Honor Guard……………………………………………………………….19 Crossing Guards………………………………………………………….19 School Resource Officers…………………………………………...19 Rise Above Program…………………………………………………...19 Explorers……………………………………………………………………..20 Reserves……………………………………………………………………….21 Sentinels……………………………………………………………………...21 Special Events...…………………………………………………………..21 Citizens Police Academy…………………………………………….22 National Night Out……………………………………………………..22 Shop With a Cop………………………………………………………….22 Investigations Bureau…………………………………………………………...23-27 General Investigations………………………………………………..24 FBI Task Force……………………………………………………………..25 Ozarks Drug Enforcement Team………………………………..25 Southwest -

Sample Letter to Member Injured in the Line of Duty

Dear Colleague, I was sorry to hear that you were injured on the job. Even though you are still recovering, there are some procedures of which you should be aware regarding your injury on the job. 1. Injury on the job is referred to as “Injury in the Line of Duty” and is covered by the Department of Education’s Personnel Memorandum No. 4 of October 21, 2002. The memorandum requires that you must notify the Administration of any accident or injury within 24 hours. At the time of the injury, a Comprehensive Injury Report should be filed with the Administration. If you cannot write the report, a colleague may assist. You should try to fill out the report before you leave school that day. In the report, the specific cause of the injury should be cited and the circumstances surrounding the incident or accident clearly stated. If you were injured in the performance of some duty specifically assigned by an administrator, it is important to state that the administrator directed you to perform that duty. You should ask for a copy of the report. If you leave school without notifying the Administration, and are absent the next day, when you call the school to report your absence you must tell them that you are absent as the result of an accident you had in school. Ideally, you should talk directly to the principal. You should also ask that a Comprehensive Injury Report Form be sent to you so that you can fill it out and return it as soon as possible. -

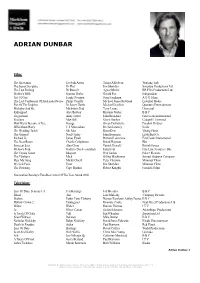

Adrian Dunbar

ADRIAN DUNBAR Film: The Snowman Frederik Aasen Tomas Alfredson Working Title The Secret Scripture Dr Hart Jim Sheridan Scripture Productions Ltd The Last Furlong Dr Russell Agnes Merlet RR Film Productions Ltd Mother's Milk Seamus Dorke Gerald Fox Independent Act Of God Frank O'connor Sean Faughnan A O G Films The Last Confession Of Alexander Pearce Philip Conolly Michael James Rowland Essential Media Eye Of The Dolphin Dr James Hawk Michael D.sellers Quantum Entertainment Mickybo And Me Mickybo's Dad Terry Loane Universal Kidnapped Alex Balfour Brendan Maher B B C Triggerman Andy Jarrett John Bradshaw First Look International Shooters Max Bell Glenn Durfort Catapult / Universal How Harry Became A Tree George Goran Paskaljevic Paradox Pictures Wild About Harry J. J. Macmohan Declan Lowney Scala The Wedding Tackle Mr. Mac Rami Dvir Viking Films The General Noel Curley John Boorman Little Bird Co. Richard Iii James Tyrell Richard Loncraine First Look International The Near Room Charlie Colquhoun David Hayman Bbc Innocent Lies Alan Cross Patrick Dewolf British Screen Widow's Peak Godfrey Doyle-counihan John Irvin Fine Line Features / Bbc The Crying Game Maguire Neil Jordan Palace Pictures The Playboys Mick Gillies Mackinnon Samuel Godwyn Company Hear My Song Micky O'neill Peter Chelsom Miramax Films My Left Foot Peter Jim Sheridan Miramax Films The Dawning Capt. Rankin Robert Knights Ferndale Films Nomination Barclay's Tma Best Actor Of The Year Award 2002 Television: Line Of Duty, Seasons 1-5 Ted Hastings Jed Mecurio B B C Blood Jim Lisa -

Britbox Stars Talk About What Tv Moved, Amused and Inspired Them

BRITBOX STARS TALK ABOUT WHAT TV MOVED, AMUSED AND INSPIRED THEM JAMES NESBITT The Cold Feet actor’s top picks on BritBox: ● Cracker ● Prime Suspect ● Boys From The Blackstuff ● Black Adder ● Fawlty Towers ● The Good Life ● The Two Ronnies ● The Young Ones “The notion of being part of a new platform that really does try and bring different genres together but all underscored by a certain quality is very exciting.” Is there anything you watched growing up that you have great memories of? I first really recall, in terms of drama, Boys From The Blackstuff. I thought it was just extraordinary. And The Monocled Mutineer. A lot of those programmes really gripped me. I also grew up watching a lot of comedy with my mum actually. Fawlty Towers was must see. I was quite young for that but I immediately understood the absurdity, the pain of it, the farce. The Two Ronnies I used to love. My mum actually looked a bit like Ronnie Corbett which was a bit odd! I also grew up watching sport and still love Match of The Day. To grow up on all those dramas and now to be part of it has been one of the great journeys to be honest. Can you tell us why you were interested in getting involved in the launch of BritBox? Television has been very, very good to me. I’ve been working for a long time now. I’m one of those people who people think is the youngest on set but I’m by far the oldest! I’ve been working since I left drama school in 1988. -

FINAL FORMATION M-Day Guard & Reserve

FINAL FORMATION M-day Guard & Reserve ETS/NO DEPLOYMENTS/LINE OF DUTY INJURIES 1. If you have Tricare Reserve Select it will end the day of your ETS. a. You can convert to Continued Health Care Benefit Program the Quarterly cost for an individual is $1,553 and for a family $3,500. b. If you had Tricare Dental, it will end the day of your ETS. c. Benefeds for vision, it will end the day of your ETS. 2. You are eligible for VA home loan as well as VA compensation and healthcare a. To be eligible for VA healthcare you will have to file for VA compensation first. b. When filing for compensation use a Veteran Service Officer (VSO). They know the VA system and they cost nothing. A couple of Veteran Service Officer Organizations are County VSO, American Legion, VFW, DAV, and Purple Heart Association. To find Veteran Service Officer you can go to VA website: www.va.gov . c. When filing for compensation, make sure to have your Doctor’s name and address if you did not use a Military Treatment Facility (MTF). You need to get all military and civilian medical records. Do not count on the VA to be able to get them. It severely stalls the claim and most times they are not successful. d. After your compensation is approved. Bring your 10-10EZ form or go into the VA hospital to register for VA healthcare. e. Anything that is service connected is always 100% covered by the VA. The VA will see you for non-service connected issues, but you may charge a copay. -

Dod 7000.14 - R

DoD 7000.14 - R DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT REGULATION VOLUME 5: “DISBURSING POLICY” UNDER SECRETARY OF DEFENSE (COMPTROLLER) DoD 7000.14 - R DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT REGULATION VOLUME CROSSWALK: "ARCHIVED" UNDER SECRETARY OF DEFENSE (COMPTROLLER) DoD2B 7000.14-R Financial Management Regulation Volume 5, Chapter 1 *July 2021 VOLUME 5, CHAPTER 1: “PURPOSE, ORGANIZATION, AND DUTIES” SUMMARY OF MAJOR CHANGES All changes are in blue font. Substantive revisions are denoted by an asterisk (*) symbol preceding the section, paragraph, table, or figure that includes the revision. Unless otherwise noted, chapters referenced are contained in this volume. Hyperlinks are in bold, italic, blue, and underlined font. The previous version dated October 2019 is archived. PARAGRAPH EXPLANATION OF CHANGE/REVISION PURPOSE All Updated hyperlinks and formatting to comply with current Revision administrative instructions. 1-1 DoD2B 7000.14-R Financial Management Regulation Volume 5, Chapter 1 *July 2021 Table of Contents 0101 GENERAL ........................................................................................................... 3 010101. Purpose ................................................................................................................. 3 010102. Authoritative Guidance ........................................................................................ 3 010103. Recommended Changes and Requests for Deviation or Exception ..................... 3 010104. Use of Volume 5 ................................................................................................. -

GO357 Line of Duty Death

GREELEY POLICE DEPARTMENT General Order 357.00 Reviewed: 01/19 357.00 LINE OF DUTY DEATH 357.01 Definitions: Line-of-Duty Death: Any action, felonious, accidental or natural, which claims the life of a Greeley Police Officer who is performing work-related functions either while on or off duty. Survivors: Immediate family members of the deceased officer: spouse, children, parents, siblings, fiancée, and/or significant others. Beneficiary: Those designated by the officer as recipient(s) of specific death benefits. Benefits: Financial payments made to the family to insure financial stability following the loss of a loved one. Funeral Payments: Financial payments made to the surviving family of an officer killed in the line-of-duty, which are specifically earmarked for funeral expenses. 357.02 Procedures and Responsibilities: It shall be the responsibility of the Chief of Police or a Deputy Chief (NOTIFICATION OFFICER) in cooperation with the Coroner’s Office to properly notify the next of kin of an officer who has suffered severe injuries or died. The name of the deceased officer must NEVER be released by the department before the survivors are notified. If there is knowledge of a medical problem with an immediate survivor, medical personnel should be available at the residence to coincide with the death notification. The family should learn of the death from the department first and not from the press or other sources. If there is an opportunity to get to the hospital prior to the demise of the officer, DO NOT wait. If the family requests to visit the hospital, they should be transported by police department vehicle.