Making Meaning and Making Monsters: Democracies, Personalist Regimes and International Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moral Framing and Charitable Donation: Integrating Exploratory Social Media Analyses and Confirmatory Experimentation

Hoover, J., et al. (2018). Moral Framing and Charitable Donation: Integrating Exploratory Social Media Analyses and Confirmatory Experimentation. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1): 9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.129 ORIGINAL RESEARCH REPORT Moral Framing and Charitable Donation: Integrating Exploratory Social Media Analyses and Confirmatory Experimentation Joe Hoover*, Kate Johnson*, Reihane Boghrati†, Jesse Graham* and Morteza Dehghani‡ Do appeals to moral values promote charitable donation during natural disasters? Using Distributed Dictionary Representation, we analyze tweets posted during Hurricane Sandy to explore associations between moral values and charitable donation sentiment. We then derive hypotheses from the observed associations and test these hypotheses across a series of preregistered experiments that investigate the effects of moral framing on perceived donation motivation (Studies 2 & 3), hypothetical donation (Study 4), and real donation behavior (Study 5). Overall, we find consistent positive associations between moral care and loyalty framing with donation sentiment and donation motivation. However, in contrast with people’s perceptions, we also find that moral frames may not actually have reliable effects on charitable donation, as measured by hypothetical indications of donation and real donation behavior. Overall, this work demonstrates that theoretically constrained, exploratory social media analyses can be used to generate viable hypotheses, but also that such approaches should be paired with rigorous controlled experiments. Keywords: Moral Psychology; Charitable Donation; Natural Language Processing; Social Media The 900-mile-wide Hurricane Sandy hit the Atlantic Coast charitable donation in public discourse by modeling the of the United States on October 29th, 2012 with record- language used to frame charitable donation in the wake of breaking rainfall and 80-mile-per-hour winds. -

Ezra M. Markowitz [email protected] |

Ezra M. Markowitz [email protected] | www.ezramarkowitz.com Assistant Professor of Environmental Decision-Making Department of Environmental Conservation 303 Holdsworth Hall University of Massachusetts Amherst Amherst, MA 01003 Education 2012 Ph.D. Environmental Sciences, Studies & Policy. University of Oregon. Dissertation: Affective and moral roots of environmental stewardship: The role of obligation, gratitude and compassion Committee: Sara Hodges, Azim Shariff, Paul Slovic, Ron Mitchell, Kari Norgaard 2008 M.S. Psychology. University of Oregon. Thesis: Did you just see that? Making sense of environmentally relevant behavior Advisor: Bertram Malle 2007 B.A. Psychology. Vassar College. Departmental and general honors. Advisors: Randy Cornelius, Susan Trumbetta Appointments 2014- Assistant professor. University of Massachusetts Amherst. 2013-2014 Postdoctoral research fellow. Earth Institute. Columbia University. 2013-2014 Visiting postdoctoral research associate. PIIRS. Princeton University. 2013-2014 Fellow. FrameWorks Institute. Washington, DC. 2012-2013 Postdoctoral research associate. PIIRS. Princeton University. 2011-2012 Scholar-in-residence. School of Communication. American University. Professional and Teaching Experience 2012 Consultant. FrameWorks Institute. Washington, DC. 2012 Consultant. ecoAmerica. Washington, DC. 2010-2012 Gallup research scholar. Gallup. Princeton, NJ. 1 2010-2011 Director. Campus Conservation Corps. University of Oregon. 2010 Instructor. Psychology of Climate Change, Univ. of Oregon. 2009-2010 Graduate teaching fellow. Intro to Env. Studies; Statistics. Univ. of Oregon. 2008-2009 Graduate intern. Institute for a Sustainable Environment. Eugene, OR. 2008-2013 Senior staff. PolicyInteractive. Eugene, OR. Awards, Grants, Honors, Scholarships 2013 DISCCRS VIII Symposium (invited, attended). DISCCRS.org. 2012 Outstanding student paper award. Amer. Psych. Assoc. Divisions 9 & 34. 2011 Best paper award. 9th Biennial Conference on Environmental Psychology. -

Terrorism Knows No Borders

TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS October 2019 his is a special initiative for SEFF to be associated with, it is one part of a three part overall Project which includes; the production of a Book and DVD Twhich captures the testimonies and experiences of well over 20 innocent victims and survivors of terrorism from across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland. The Project title; ‘Terrorism knows NO Borders’ aptly illustrates the broader point that we are seeking to make through our involvement in this work, namely that in the context of Northern Ireland terrorism and criminal violence was not curtailed to Northern Ireland alone but rather that individuals, families and communities experienced its’ impacts across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and beyond these islands. This Memorial Quilt Project does not claim to represent the totality of lives lost across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland but rather seeks to provide some understanding of the sacrifices paid by communities, families and individuals who have been victimised by ‘Republican’ or ‘Loyalist’ terrorism. SEFF’s ethos means that we are not purely concerned with victims/survivors who live within south Fermanagh or indeed the broader County. -

Empathy Through Data Loneliness Through the Lens of Data Visualization

Empathy Through Data Loneliness through the lens of data visualization By Sananda Dutta A thesis presented to OCAD University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Design in Digital Futures. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2021. Empathy Through Data Sananda Dutta Creative Commons Copyright Notice Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 2.5 Canada License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode You are free to: Share - copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Under the following conditions: Attribution - You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. No additional restrictions - You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. 1 Empathy Through Data Sananda Dutta ABSTRACT This research examines strategies aimed at fostering empathy through data visualizations. Loneliness experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic (during May, July and September 2020) is used as a case study to explore alternate ways of representing data. Along with ways to humanize data representation and curb Statistical numbing, this research uses metaphors to encode sensitive data to help visually represent people suffering loneliness in Ontario during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research amalgamates ‘affect theory’ with concepts of ‘arithmetic of emotions’ and ‘compassion fade’ to try and create a solution for issues related to the ways in which we respond to sensitive issues. -

Self-Other Similarity and Its Effects on Insensitivity to Mass Suffering

Self-‐Other Similarity and Its Effects on Insensitivity to Mass Suffering Ka Ho Tam Thesis for Honors Research Project in Psychology Northeastern University April 2016 Tam 2 Abstract Past studies show that our compassion toward suffering others when decreases we are exposed to numerous suffering individuals as opposed to a single sufferer. This phenomenon is called the “collapse of compassion”. The present research examines the effects of self-‐other similarity on our insensitivity to suffering. mass Based on existing evidence that self-‐other similarity can promote compassion, we e xpected the collapse of compassion to disappear diminish or when similarity is experimentally induced. In a single experiment involving 242 undergraduate participants , we manipulated the level of self-‐other similarity priming by participants with Shared Human xperiences E (SHE) that highlighted commonalities between participants the and children in Ethiopia. Participants in the control condition were primed with cultural-‐specific experiences that were unique to the Ethiopian population. We then presented participants with a description a of poverty-‐stricken village in Ethiopia, followed by images of either one or eight suffering children from that village. Results of the experiment supported the opposite orig of our inal hypothesis. Participants in the SHE exhibited condition the collapse of compassion, whereas participants in the reported control condition sig nificantly more compassion for a group of suffering children than for a single child. Our research demonstrates that although self-‐other similarity can promote compassion in a single victim context, this effect is reversed when multiple victims present, are leading to the collapse of compassion. Future studies further may explore the factors that mediate the relationship between self -‐other similarity and the collapse of compassion. -

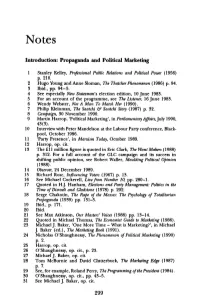

Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing

Notes Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing 2 Stanley Kelley, Professional Public Relations and Political Power (1956) p. 210. 2 Hugo Young and Anne Sloman, The Thatcher Phenomenon (1986) p. 94. 3 Ibid., pp. 94-5. 4 See especially New Statesman's election edition, 10 June 1983. 5 For an account of the programme, see The Listmer, 16 June 1983. 6 Wendy Webster, Not A Man To Matcll Her (1990). 7 Philip Kleinman, The Saatchi & Saatchi Story (1987) p. 32. 8 Campaign, 30 November 1990. 9 Martin Harrop, 'Political Marketing', in ParliamentaryAffairs,July 1990, 43(3). 10 Interview with Peter Mandelson at the Labour Party conference, Black- pool, October 1986. 11 'Party Presence', in Marxism Today, October 1989. 12 Harrop, op. cit. 13 The £11 million figure is quoted in Eric Clark, The Want Makers (1988) p. 312. For a full account of the GLC campaign and its success in shifting public opinion, see Robert Waller, Moulding Political Opinion (1988). 14 Obse1ver, 24 December 1989. 15 Richard Rose, Influencing Voters (1967) p. 13. 16 See Michael Cockerell, Live from Number 10, pp. 280-1. 17 Quoted in HJ. Hanham, Ekctions and Party Management: Politics in the Time of Disraeli and Gladstone ( 1978) p. 202. 18 Serge Chakotin, The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Propaganda (1939) pp. 131-3. 19 Ibid., p. 171. 20 Ibid. 21 See Max Atkinson, Our Masters' Voices (1988) pp. 13-14. 22 Quoted in Michael Thomas, The Economist Guide to Marketing (1986). 23 Michael J. Baker, 'One More Time- What is Marketing?', in Michael J. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School MOTIVATING

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School MOTIVATING ENGAGEMENT WITH SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSUES THROUGH COMPASSION TRAINING: A MULTI-METHOD RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL A Dissertation in Psychology by Sinhae Cho © 2020 Sinhae Cho Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2020 ii The dissertation of Sinhae Cho was reviewed and approved by the following: José A. Soto Associate Professor of Psychology Sherwin Early Career Professor in the Rock Ethics Institute Dissertation Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Robert W. Roeser Professor of Human Development and Family Studies Bennett Pierce Professor of Caring and Compassion Co-Chair of Committee C. Daryl Cameron Assistant Professor of Psychology Research Associate in Rock Ethics Institute Michael N. Hallquist Assistant Professor of Psychology Assistant Professor of Institute for Computational and Data Sciences Kristin A. Buss Professor of Psychology Professor of Human Development and Family Studies Head of the Department of Psychology iii ABSTRACT To address issues of racial disparities in the US and effect lasting social changes, it is essential for members of privileged groups to learn about the experiences of marginalized individuals and groups. However, this kind of empathic engagement around social justice issues is often avoided by privileged group members due to the potentially high emotional costs associated with engaging with these issues. This multi-method, randomized controlled trial examined a two-week, online-based, self-administered -

Solidarity in the Media and Public Contention Over Refugees in Europe

Solidarity in the Media and Public Contention over Refugees in Europe This book examines the ‘European refugee crisis’,offering an in-depth comparative analysis of how public attitudes towards refugees and humanitarian dispositions are shaped by political news coverage. An international team of authors address the role of the media in contesting solidarity towards refugees from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. Focusing on the public sphere, the book follows the assumption that solidarity is a social value, political con- cept and legal principle that is discursively constructed in public contentions. The ana- lysis refers systematically and comparatively to eight European countries, namely, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Treatment of data is also original in the way it deals with variations of public spheres by combining a news media claims-making analysis with a social media reception analysis. In particular, the book highlights the prominent role of the mass media in shaping national and transnational solidarity, while exploring the readiness of the mass media to extend thick conceptions of solidarity to non-members. It proposes a research design for the comparative analysis of online news reception and considers the innovative potential of this method in relation to established public opinion research. The book is of particular interest for scholars who are interested in the fields of Eur- opean solidarity, migration and refugees, contentious politics, while providing an approach that talks to scholars of journalism and political communication studies, as well as digital journalism and online news reception. Manlio Cinalli holds a Chair of Sociology at the University of Milan and is Associate Research Director at CEVIPOF (CNRS – UMR 7048), Sciences Po Paris. -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA. -

Running Head: ADVERSITY and COMPASSION 1

Running head: ADVERSITY AND COMPASSION 1 Past Adversity Protects Against the Numeracy Bias in Compassion Daniel Lim & David DeSteno Northeastern University Contact Information: David DeSteno Dept. of Psychology Northeastern University Boston, MA 02115 Email: [email protected] July 1, 2019 In Press, Emotion ADVERSITY AND COMPASSION 2 Abstract Past research has suggested that one problematic limitation of compassion is its seeming resistance to increase in response to growing numbers of targets in distress. This insensitivity to numeracy results in the dampening of compassion when faced with mass suffering. Given that emerging evidence suggests that facing past adversity in life may foster compassion and a general prosocial orientation, we explored whether those who have experienced greater adversity show a resistance to this numeracy bias. In a series of four experiments, we demonstrate not only that those who have experienced greater adversity readily overcome the numeracy bias in compassion, but also that beliefs regarding their ability to be efficacious in helping others underlie this link. Of import, we also show that direct manipulation of such efficacy beliefs can remove the numeracy bias in compassion typically found among those who have not endured significant life adversity. Finally, we explore the ability of adversity to engender prosocial donations to those in need via mechanisms involving compassion and efficacy beliefs. Keywords: compassion, adversity, numeracy bias, self-efficacy, prosocial behavior ADVERSITY AND COMPASSION 3 Past Adversity Protects Against the Numeracy Bias in Compassion Compassion is a powerful moral emotion capable at times of driving decisions and behaviors aimed at alleviating the suffering of others (DeSteno, 2015; Goetz, Keltner & Simon- Thomas, 2010). -

Willing to Help, but Lacking Discernment: the Effects of Victim Group Size on Donation Behaviors Devin Lunt a Dissertation Submi

Willing to Help, but Lacking Discernment: The Effects of Victim Group Size on Donation Behaviors Devin Lunt A Dissertation Submitted to University of Texas-Arlington College of Business Under the Supervision of Dr. Traci Freling In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN MARKETING University of Texas-Arlington Arlington, TX May, 2016 1 Abstract Researchers and practitioners in the nonprofit domain have long lamented the tendency of people to offer greater aid to a smaller number of victims, in essence de-valuing the lives of victims as the number of victims grows. This is often referred to as Compassion Fade-a greater responsiveness among potential donors to individuals and small numbers of people in need, and lower sensitivity toward larger groups of victims (Markowitz et al. 2013) This dissertation consists of three essays exploring compassion fade and the specific biases that exemplify this phenomenon. The first essay provides a qualitative synthesis of the compassion fade domain as a whole, including a review of current findings of psychophysical numbing, proportion dominance bias, and scope insensitivity studies. The mechanisms by which these effects occur (e.g., other-focused affect, anticipated self-focused affect, and deliberative thoughts) are discussed, along with proposed directions for future research. Demonstrations of the most often studied form of compassion fade bias—known as the “identifiable victim effect” (IVE—abound in the literature. The IVE is quantitatively synthesized in the first essay. As such, the second essay undertakes a meta-analysis of 40 articles (with 144 effect sizes derived from 225,193 observations) spanning almost 30 years suggests that victim identifiability and group size significantly affects potential donors’ helping behaviors, but not their empathetic attitudes. -

Ideology and Cabinet Selection Under Margaret Thatcher 1979-1990

Prime Ministerial Powers of Patronage: Ideology and Cabinet Selection under Margaret Thatcher 1979-1990 Abstract: This article will examine how Margaret Thatcher utilised the Prime Ministerial power of Cabinet ministerial appointment between 1979 and 1990. The article will utilise the Norton taxonomy on the parliamentary Conservative Party (PCP) to determine the ideological disposition (non-Thatcherite versus Thatcherite) of her Cabinet members across her eleven years in office. It will assess the ideological trends in terms of appointments, promotions and departures from Cabinet and it will use archival evidence to explore the advice given to Thatcher to assist her decision-making. Through this process the article will demonstrate how Thatcher was more ideologically balanced than academics have traditionally acknowledged when discussing her Cabinet selections. Moreover, the article will also demonstrate the significance attached to media presentation skills to her decision-making, thus challenging the emphasis on ideology as a dominant determinant of Cabinet selection. Keywords: Conservative Party; Margaret Thatcher; Thatcher Government 1979-1990; Ministerial Selection; Cabinet Ministers. 1 Introduction: This article contributes to the academic literature on the political leadership of Margaret Thatcher, focusing on the powers of patronage that a Prime Minister possesses in terms of Cabinet selection. The article will address the following three research questions: first, how ideologically balanced were her Cabinets; second, did she demonstrate a bias towards Thatcherites in terms of promotions into Cabinet; and, third, was there a bias towards non- Thatcherites in terms of departures from Cabinet? In answering these questions, the article will use archival evidence to gain insights into the factors shaping her decision-making on Cabinet selection.