X-KR/06/165 Sarajevo, 24 August 2007 in the NAME of BOSNIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Confidential RUF Apppeal Judgment

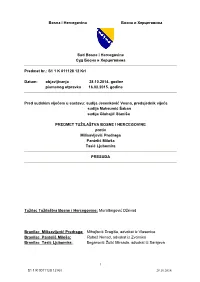

Bosna i Hercegovina Босна и Херцеговина Sud Bosne i Hercegovine Суд Босна и Херцеговина Predmet br.: S1 1 K 011128 12 KrI Datum: objavljivanja 28.10.2014. godine pismenog otpravka 16.02.2015. godine Pred sudskim vijećem u sastavu: sudija Jesenković Vesna, predsjednik vijeća sudija Maksumić Šaban sudija Gluhajić Staniša PREDMET TUŽILAŠTVA BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE protiv Milisavljević Predraga Pantelić Miloša Tasić Ljubomira PRESUDA Tužilac Tužilaštva Bosne i Hercegovine: Muratbegović Dževad Branilac Milisavljević Predraga: Mihajlović Dragiša, advokat iz Vlasenice Branilac Pantelić Miloša: Rubež Nenad, advokat iz Zvornika Branilac Tasić Ljubomira: Beganović Žutić Mirsada, advokat iz Sarajeva 1 S1 1 K 0011128 12 Krl 28.10.2014. I Z R E K A I. K R I V I Č N I P O S T U P A K ...................................................................................... 11 A. O P T U Ž N I C A I G L A V N I P R E T R E S ............................................................. 11 B. P R O C E S N E O D L U K E ...................................................................................... 13 (a) Odluka o isključenju javnosti za dio pretresa.................................................. 13 (b) Svjedoci pod mjerama zaštite .......................................................................... 13 (c) Odluka o usvajanju prijedloga Tužilaštva za prihvatanje utvrđenih činjenica u postupcima pred MKSJ ....................................................................................... 14 (d) Izmjena redoslijeda izvođenja dokaza (član 261. -

Kontinuitet Genocida Nad Bošnjacima U Višegradu: Studija Slučaja Selo Barimo

SAGLEDAVANJA KONTINUITET GENOCIDA NAD BOŠNJACIMA U VIŠEGRADU: STUDIJA SLUČAJA SELO BARIMO Ermin KUKA UDK 3221:141]:28 341.322.5(497.6 Višegrad)”1992/1995” DOI: Sažetak: Ideologija, politika i praksa stvaranja etnički čiste srpske države, tzv. “Velike Srbije”, nalazila se u fokusu interesiranja velikosrpske ideologije, još od vremena s kraja XVIII stoljeća. Ta i takva ideologija je figurirala s idejom stvaranja etnički čistih teritorija na kojima bi isključivo i samo živjeli Srbi, a koja je podrazumijevala i teritoriju Bosne i Hercegovine. Za druge i drugačije, pa čak niti za nacionalne manjine, u tim zamislima nema mjesta. Takav projekt je bilo jedino moguće ostvariti putem nasilja, tj. kroz vršenje strašnih i užasnih zločina nad nesrbima, prije svega nad Bošnjacima u Bosni i Hercegovini, uključujući i zločin genocida. Počev još od Prvog svjetskog rata, zatim Drugog svjetskog rata, te u vremenu posljednje agresije na Republiku Bosnu i Hercegovinu u periodu 1992–1995. godine, evidentna je otvorena i neskrivena namjera stvaranja tzv. “Velike Srbije”. Ona je obilježena, prije svega, kontinuiranim vršenjem brojnih oblika zločina protiv čovječnosti i međunarodnog prava nad Bošnjacima, uključujući i zločin genocida. Posebno je to bilo izraženo na području Istočne Bosne, uključujući i grad Višegrad. Prezentirana studija slučaja na primjeru sela Barimo, kao istraživane mikrolokacije, jasan je pokazatelj kontinuiteta zločina genocida nad Bošnjacima, ali i namjere zločinaca o stvaranju etnički čistih teritorija na području Višegrada. Radi se, dakle, o kontinuitetu namjere i nastojanja velikosrpskih ideologa o uklanjanju svih Bošnjaka s područja Istočne Bosne i grada Višegrada, uključujući i selo Barimo. Zaključak je da je selo Barimo jasan pokazatelj kontinuiteta genocidnih namjera na području Višegrada, ali i borbe Bošnjaka da, poslije svakog stradanja, nastoje opstati na tim prostorima, na kojima su vjekovima živjeli. -

Bosna I Hercegovina FEDERACIJA BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE

Bosna i Hercegovina FEDERACIJA BOSNE I Bosnia and Herzegovina FEDERATION OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FEDERAL MINISTRY OF HERCEGOVINE FEDERALNO MINISTARSTVO DISPLACED PERSONS AND REFUGEES RASELJENIH OSOBA I IZBJEGLICA Broj: 03-36-2-334-5022/19 Sarajevo, 20.05.2020.godine Na osnovu člana 56. Zakona o organizaciji organa uprave u Federaciji BiH („Službene novine Federacije BiH“ broj: 35/05), a u vezi sa objavljenim Javnim pozivom za program pomoći održivog povratka „Podrška zapošljavanju/samozapošljavanju povratnika u poljoprivredi u period 2020. i 2021.godine“, broj: 03-36-2-334-1/19 od 09.12.2019. godine, u skladu sa Procedurama za izbor korisnika za „Program podrške zapošljavanju/samozapošljavanju povratnika u poljoprivredi u periodu 2020. i 2021.godine“, broj: 03-36-2-334-2/19 od 12.12.2019, na prijedlog Komisije za razmatranje prijava po Javnom pozivu, imenovane Rješenjem ministra, broj: 03-36-2-334-3/19 od 12.12.2019.godine, federalni ministar raseljenih osoba i izbjeglica, donosi ODLUKU O UTVRĐIVANJU RANG LISTE POTENCIJALNIH KORISNIKA za program pomoći održivog povratka „Podrška zapošljavanju/samozapošljavanju povratnika u poljoprivredi u periodu 2020. i 2021.godine“ za entitet Republika srpska I Ovom odlukom vrši se rangiranje potencijalnih korisnika pomoći na osnovu ispunjavanja/neispunjavanja općih i posebnih kriterija, odnosno ukupnog broja bodova. II Rang lista potencijalnih korisnika pomoći koji ispunjavaju opće kriterije iz Javnog poziva raspoređenih prema opštinama i programima pomoći kako slijedi: Regija Banja Luka Banja Luka- Mehanizacija RB IME /ime oca/ PREZIME ADRESA GRAD/OPĆINA PROGRAM POMOĆI NAMJENA BODOVI Ivanjska Pezić 1 Pezić/Ilija/Mato Banja Luka 1. Mehanizacija Traktor 40-45 KS polje 60 Čelinac- Finansijska sredstva Čelinac Novac-mašine, oprema 1 Nuhić (Selim) Mujo V.Mišića 44 7. -

Pregledati Cjelokupno Izdanje BAŠTINA 4. SJEVEROISTOČNE BOSNE

BAŠTINA SJEVEROISTOČNE BOSNE BROJ 4. 2011. ČASOPIS ZA BAŠTINU, KULTURNO-HISTORIJSKO I PRIRODNO NASLIJEĐE Northeast Bosnia's Heritage Number 4, 2011. Heritage magazine, Culture-historical and natural heritage Glavni i odgovorni urednik: doc. dr. sc. Edin Mutapčić Urednik u redakciji: mr. sc. Rusmir Djedović Članovi redakcije: Benjamin Bajrektarević, prof., direktor Zavoda; prof. dr. sc. Amira Turbić- Hadžagić; prof. dr. sc. Ivan Balta; Samir Halilović, prof., doc. dr. sc. Adnan Tufekčić, doc. dr. sc. Izet Šabotić; doc. dr. sc. Omer Hamzić; Munisa Kovačević, prof. (sekretar) Izdavač: JU Zavod za zaštitu i korištenje kulturno-historijskog i prirodnog naslijeđa Tuzlanskog kantona Za izdavača: Benjamin Bajrektarević, direktor Zavoda Naslovna strana: Novoformirana nekropola stećaka na Rajskom jezeru kod Živinica ISSN 1986-6895 Tuzla, 2012. SADRŽAJ PROŠLOST Edin Šaković, prof. Rekognosciranje lokaliteta Grabovik/Zaketuša (Općina Srebrenik) ......... 10 Dr. Thomas Butler Bogumili – kulturni sinkretizam ............................................................................. 20 Mensura Mujkanović, prof. Izrada proizvoda od zemlje u okolini Tešnja od neolita do savremenog doba .................................................................................................................................... 24 Edhem Omerović Pisani tragovi o selu Goduš ........................................................................................ 38 Almir Mušović, prof. Realizacija školskog projekta „Neolit u Tuzli“ ......................................................... -

In the Name of Bosnia and Herzegovina!

SUD BOSNE I HERCEGOVINE Ref number: X-KRl06/165 Sarajevo. 24 August 2007 IN THE NAME OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA! The Court of Bosnia and Her::egovina. SectiOIl I for War Crimes, silling in the Panel composed of JI/dge Hillllo Vucinie, as the Presiding Judge, Judge Shireel1 Avis Fishel' and Judge Paul M. Brillllal1, as lIIembers of the Panel, including the Legal Associate Oienana Oeljkii: Blagojevie as the Record-lCIker. in the crimillal case against the accused Nellad Tanaskovie, for the criminal offense of Crimes against Humanity in violation of Al'licle 172 (I) (a), (d), (e), (f). (gJ, (17) and (k) ill conj/mc/ioll with Article 180 (I) of the Crimi/wi Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH CC). upon the IndictmeJII of the Prosecutor's Office of BiH Ref number KT-RZ-146/05 dated 29 Septelllber 2006, after (he public main (rial. which \Vas port~v closed to the public. in the presence of the Prosecutor of the ProseCutor's Office 0/ BiH, David Sch1l'endimon, Ihe accused Nenad Tanaskovic ill person and Itis Defellse COl/llsel Dragan Borov[;onil1, ollorney-ot-Iall' ,/i'om Sokolac, and Radmila Radosav/jevie, allol'l1ey-at-lall' /1'0111 Visegrad followillg the deliberGlion and voting, on 24 August 2007 rendered and public~)1 annol/nced the/ol/owing: VERDICT THE ACCUSED: NENAD TANASKOVIC a/k/a "Neso", SOI7 o/Momir and SICJ/1ojka, bo1'/7 011 20 November 1961 in the vii/age 0/ DOI?ia L[jeska, Visegrad "4unicipality. Personal Idel1fijicClliol7 Number (JMBG): 2011961133652. Serb. citizen 0/ BiN. -

Univerza V Novi Gorici Fakulteta Za Podiplomski Študij

UNIVERZA V NOVI GORICI FAKULTETA ZA PODIPLOMSKI ŠTUDIJ POVIJEST DINARSKOG KRŠA NA PRIMJERU POPOVA POLJA ZGODOVINA POZNAVANJA DINARSKEGA KRASA NA PRIMERU POPOVEGA POLJA DISERTACIJA Ivo Lučić Mentorja: prof. dr. Andrej Kranjc prof. dr. Petar Milanović Nova Gorica, 2009 Izjavljujem da je ova disertacija u cijelosti moje autorsko djelo. Hereby I declare this thesis is entirely my author work. Izvadak Povijest poznavanja Dinarskog krša na primjeru Popova polja (Pokušaj holističke interpretacije krša uz pomoć karstologije, povijesti okoliša i kulturnog krajolika) Tekst predstavlja rezultat analize poznavanja, upotrebe i obilježavanja jednog istaknutog krškog krajolika, temeljeći se isključivo na uvidu u dostupnu literaturu i pisane izvore. Te tri vrste odnosa u značajnoj mjeri su povezane sa znanstvenim područjima: poznavanje s prirodnim znanostima, upotreba s tehničkim znanostima i obilježavanje s društveno- humanističkim znanostima. Prirodoslovlje je naglašeno zastupljeno s fizičkim geoznanostima koje prodiru u Popovo polje krajem 19. stoljeća, zajedno s karstologijom. Upotreba se gotovo isključivo odvijala tradicionalnim sredstvima do sredine 20. stoljeća, prevladavajuće djelatnosti ostale su tradicionalne do početka zadnje trećine toga stoljeća, a modernizacija je rezultirala snažnom deagrarizacijom, pustošnom depopulacijom i dalekosežnim ekološkim štetama. Obilježavanje krajolika još duže je zadržalo tradicionalni pečat dubinski temeljen na mitološkim kulturnim strukturama. One su, premda uglavnom jedinstvene, kroz političku modernizaciju rezultirale još snažnijom podjelom prostora. Kulturna povijest primala je ovaj prirodno jedinstven prostor – promatran na bazičnoj razini kao Popovo polje i u najširem smislu kao Dinarski krš – kao dijelove različitih društvenih cjelina, što mu je dalo različite povijesne uloge i različite identitete. Do kraja 20. stoljeća dominantna upotreba i obilježavanje ovih prostora gotovo uopće nisu primile poruke izuzetnosti koje im je slala karstologija. -

BOSNIA and HERZEGOVINA PROSECUTOR's OFFICE of Bih SARAJEVO No: KT-RZ-146/0S Sarajevo,29 September 2006

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA PROSECUTOR'S OFFICE OF BiH SARAJEVO No: KT-RZ-146/0S Sarajevo,29 September 2006 COURT OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA - Preliminary Hearing Judge - Pursuant to Articles 35(2)(h), 226(1) and 227 of the Criminal Procedure Code of Bosnia and Herzegovina ('BiH CPC'), I hereby file this INDICTMENT Against: Tanaskovic Nenad a.k.a. "Neso", son ofMomir and mother Stanojka, born on 20th November 1961 in the village of Donja Lijeska, Visegrad municipality, citizen's identification no. 2011961133652, Serb, citizen of BiII, residing in Donja Lijeska no. 16, Visegrad Municipality, unmarried, literate, completed secondary school, qualified driver, employed, no prior convictions, military service completed in 1981 in Siavonska Pozega, arrested by SIPA on 11 July 2006 at 15:05, transferred to the Court of BiR Detention Unit on the same day at 18:35, originally detained pursuant to the decision of the Court ofBiH made on 12 July 2006 ordering detention until 11 August 2006 at 15:05, and currently detained pursuant to the decision of the Court ofBiH made on 9 August 2006 ordering detention until 9 October 2006. Because: In the period from April through June of 1992, during an armed conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as a reserve policeman of the Viliegrad Public Security Station, of the Trebinje Security Services Center, he participated in a widespread or systematic attack of the Army of the Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina ("the Army"), police and paramilitary formations on Bosnian Muslim civilian population on the territory of -

Preliminarna Rang Lista Čajniče

JAVNI POZIV FMROI 2019 – PRELIMINARNA RANG LISTA ČAJNIČE Red.br. Ime i prezime Adresa sanacije Broj bodova Sadašnja adresa 1. Medošević (Hamdija) Safet Batotići, Čajniče 110 Batotići, Čajniče 2. Bekto (Salko) Senad Đakovići-Zaborak, Čajniče 110 Đakovići bb, Čajniče 3. Efendić (Nurif) Salih Slatina bb, Čajniče 110 Slatina-Turkovići, Čajniče 4. Habibović (Adil) Edin Miljeno bb, Čajniče 110 Miljeno bb, Čajniče 5. Srna Tahir Nusret G.Stopići bb Čajniče 100 G.Stopići bb Čajniče 6. Ćoso Hadžan Halil Avlija Čajniče 100 Butmirskog bataljona 62 Ilidža 7. Hasović Salko Ifeta Hasovići, Čajniče 100 Malra br 13/II-99, Sarajevo 8. Imamović (Ferid) Vehid Đakovići bb, Čajniče 100 G. Kromolj do 30, Sarajevo 9. Fazić (Arif) Suljo Milijeno, Čajniče 100 Milijeno, Čajniče 10. Čeljo (Amir) Nura Međurječje bb, Čajniče 100 11. Prljalča (Adem) Hamed Dubac, Čajniče 75 Lužansko Polje 59, Sarajevo 12. Sudić (Šerif) Ćamila Sudići bb, Čajniče 65 Edina Plakala 32, Goražde Napomena: Svi aplikanti koji su se javili na Javni poziv a ne nalaze se na Listi potencijalnih korisnika nisu ispunili opće kriterije propisane Zakonom. Pouka o pravnom lijeku: Na objavljenu Preliminarnu rang listu svi aplikanti mogu podnjeti prigovore pismeno Federalnom ministarstvu raseljenih osoba i izbjeglica, ul. Hamdije Čemerlića 2, Sarajevo, u roku od 15 dana od dana objavljivanja Rang liste potencijalnih korisnika. Sarajevo,07.04.2020. godine KOMISIJA ZA ODABIR KORISNIKA JAVNI POZIV FMROI 2019 – PRELIMINARNA RANG LISTA FOČA RS Red.br. Ime i prezime Adresa sanacije Broj bodova Sadašnja adresa 1. Kršo (Ramo) Senad Kršovina bb, Foča RS 160 Kršovina bb, Foča RS 2. Ćedić (Ibro) Alija Zamršten Foča RS 150 Zamršten, Foča RS 3. -

Draft Confidential RUF Apppeal Judgment

Bosna i Hercegovina Босна и Херцеговина Sud Bosne i Hercegovine Суд Босне и Херцеговине Docket No. S1 1 K 011128 15 Krž 16 Delivered on: 2 June 2015 Sent out on: 23 July 2015 Before the Court Panel composed of: Judge Mirko Božović, Presiding Judge Mirza Jusufović, Panel member Judge Redžib Begić, Panel member PROSECUTOR'S OFFICE OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA v. the accused Predrag Milisavljević, Miloš Pantelić and Ljubomir Tasić SECOND-INSTANCE JUDGMENT Prosecutor of the Prosecutor's Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Dževad Muratbegović Defense Counsel for the Accused Predrag Milisavljević: Attorney Dragiša Mihajlović Defense Counsel for the Accused Miloš Pantelić: Attorney Nenad Rubež Defense Counsel for the Accused Ljubomir Tasić: Attorney Mirsada Beganović- Žutić Sud Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo, ul. Kraljice Jelene No. 88 Telefon: 033 707 100, 707 596; Fax: 033 707 155 CONTENTS SECOND-INSTANCE JUDGMENT ..................................................................................... 1 R E A S O N I N G ............................................................................................................... 5 I. PROCEDURAL HISTORY ................................................................................................ 5 II. ESSENTIAL VIOLATIONS OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE PROVISIONS ...................... 8 A. APPEAL BY DEFENSE COUNSEL FOR THE ACCUSED PREDRAG MILISAVLJEVIĆ ......................................................................................................... 8 1. Essential violations of criminal procedure -

Konačna Rang Lista Potencijalnih Korisnika Za Rekonstrukciju Stambenih Objekata – Opština Čajniče

JAVNI POZIV FMROI 2019 – KONAČNA RANG LISTA POTENCIJALNIH KORISNIKA ZA REKONSTRUKCIJU STAMBENIH OBJEKATA – OPŠTINA ČAJNIČE Red.br. Ime i prezime Adresa sanacije Broj bodova Sadašnja adresa 1. Medošević (Hamdija) Safet Batotići, Čajniče 110 Batotići, Čajniče 2. Bekto (Salko) Senad Đakovići-Zaborak, Čajniče 110 Đakovići bb, Čajniče 3. Efendić (Nurif) Salih Slatina bb, Čajniče 110 Slatina-Turkovići, Čajniče 4. Habibović (Adil) Edin Miljeno bb, Čajniče 110 Miljeno bb, Čajniče 5. Srna Tahir Nusret G.Stopići bb Čajniče 100 G.Stopići bb Čajniče 6. Ćoso Hadžan Halil Avlija Čajniče 100 Butmirskog bataljona 62 Ilidža 7. Hasović Salko Ifeta Hasovići, Čajniče 100 Malra br 13/II-99, Sarajevo 8. Haljković (Jusuf) Safet Avlija bb, Čajniče 100 Avlija bb, Čajniče 9. Imamović (Ferid) Vehid Đakovići bb, Čajniče 100 G. Kromolj do 30, Sarajevo 10. Fazić (Arif) Suljo Milijeno, Čajniče 100 Milijeno, Čajniče 11. Čeljo (Amir) Nura Međurječje bb, Čajniče 100 12. Prljalča (Adem) Hamed Dubac, Čajniče 75 Lužansko Polje 59, Sarajevo 13. Sudić (Šerif) Ćamila Sudići bb, Čajniče 65 Edina Plakala 32, Goražde NAPOMENA: Ukoliko se utvrdi da potencijalni korisnik sa konačne rang liste ima minimum stambenih uslova, isti će biti isključen iz dalje procedure za dobijanje pomoći. Sarajevo, 04.05.2020. godine KOMISIJA ZA ODABIR KORISNIKA JAVNI POZIV FMROI 2019 – KONAČNA RANG LISTA POTENCIJALNIH KORISNIKA ZA REKONSTRUKCIJU STAMBENIH OBJEKATA – OPŠTINA FOČA RS Red.br. Ime i prezime Adresa sanacije Broj bodova Sadašnja adresa 1. Kršo (Ramo) Senad Kršovina bb, Foča RS 160 Kršovina bb, Foča RS 2. Ćedić (Ibro) Alija Zamršten Foča RS 150 Zamršten, Foča RS 3. Čolpa (Muharem) Munib Zamršten. Foča RS 140 Zamršten, Foča RS 4. -

1 Promene U Sastavu I Nazivima Naselja Za Period 1948

PROMENE U SASTAVU I NAZIVIMA NASELJA ZA PERIOD 1948. - 1990. A ADA /ODŽAK/, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA MRKA ADA (SL.L. NRBIH, ANDREJ NAD ZMINCEM /ŠKOFJA LOKA/, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA 17/55) SV. ANDREJ (UR.L. LRS, 21/55) ADAMOVEC, UVEĆANO PRIPAJANJEM NASELJA DONJI ADAMOVEC, ANDREJČE /CERKVICA/, RANIJI NAZIV ZA NASELJE ANDREJČJE KOJE JE UKINUTO (UR.L. SRS, 28/90) ADOLFOVAC, RANIJI NAZIV ZA NASELJE ZVONIMIROVAC ANDREJČJE /CERKVICA/, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA ANDREJČE ADORJAN /KANJIŽA/, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA NADRLJAN (SL.L. (UR.L. SRS, 28/90) SAPV, 21/78), ANDREJEVAC /MINIĆEVO/, RANIJI NAZIV ZA NASELJA MINIĆEVO ADROVIĆI, PRIPOJENO NASELJU CRLJENICE (SL.GL. NRS, 26/45) ADŽAMOVCI, SMANJENO IZDVAJANJEM DELA NASELJA KOJI JE ANDREJEVAC /ZRENJANIN/, PRIPOJENO NASELJU ARADAC PROGLAŠEN ZA SAMOSTALNO NASELJE ZAPOLJE (N.N. SRH, ANDRENCI (DEL) /LENART/, RANIJI NAZIV ZA NASELJE ANDRENCI 44/80) (UR.L. SRS, 2/74) ADŽI MATOVO, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA HADŽI MATOVO (PREMA ANDRENCI (DEL) /PTUJ/, UŠLO U SASTAV NOVOG NASELJA NOVINCI STATUTU OPŠTINE SV. NIKOLE) (UR.L. SRS, 2/74) AGAROVIĆI, UVEĆANO PRIPAJANJEM NASELJA OBADI KOJE JE ANDRENCI /LENART/, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA ANDRENCI (DEL) UKINUTO (SL.L. NRBIH, 47/62) (UR.L. SRS, 2/74) AGIĆI, PODELJENO U NASELJA DONJI AGIĆI I GORNJI AGIĆI ANDRIJA /VIS/, RANIJI NAZIV ZA NASELJE SVETI ANDRIJA AHATOVIĆI /SARAJEVO-NOVI GRAD/, PODELJENO,DEO PRIPOJEN ANDRIJA /VIS/, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA SVETI ANDRIJA NASELJU SARAJEVO DIO A DEO NASELJU BOVNIK (SL.L. SRBIH, ANĐELIJE, UMESTO RANIJEG NAZIVA HANDELIJE 33/90) ANHOVO /NOVA GORICA/, UVAĆANO PRIPAJANJEM NASELJA AJBIK, PRIPOJENO NASELJU BOROVEC PRI KOČEVSKI REKI (UR.L. GORNJE POLJE I LOŽICE, KOJA SU UKINUTA (UR.L. -

Time for Truth

TIME FOR TRUTH Review of the Work of the War Crimes Chamber of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2005-2010 Sarajevo, 2010. Publisher Balkanske istraživačke mreže (BIRN) BIH www.bim.ba Written by Aida Alić Editors Aida Alić and Anna McTaggart Proof Readers Nadira Korić and Anna McTaggart Translated by Nedžad Sladić Design Branko Vekić DTP Lorko Kalaš Print 500 Photography All photographs in this publication are provided by the Archive of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This guidebook is part of BIRN’s Transitional Justice Project. Its production was finan ced by the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This publication is available on the website: www.bim.ba ------------------------------------------------- CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 341.322.5:343.1]:355.012(497.6)”1992/1995” ALIĆ, Aida Time for truth : review of the work of the war crimes Chamber of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2005-2010 / [written by Aida Alić] ; [translated by Nedžad Sladić ; photography Archive of the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina]. - Sarajevo : Balkanske istraživačke mreže BiH, BIRN, 2010. - 231 str. : ilustr. ; 25 cm ISBN 978-9958-9005-5-6 COBISS.BH-ID 18078214 ------------------------------------------------- SADRŽAJ 7 Introduction 9 Abbreviations 10 Glossary 12 From the Law 19 Plea Agreements 21 Bjelić Veiz (Vlasenica) 23 Četić Ljubiša (Korićanske stijene) 25 Đurić Gordan (Korićanske stijene) 27 Fuštar Dušan (logor “Keraterm”, Prijedor) 29 Ivanković Damir