Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2016 Flamenco Jazz: an Analytical Study Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/306 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 29-77 (2016) Flamenco Jazz: An Analytical Study Peter Manuel Since the 1990s, the hybrid genre of flamenco jazz has emerged as a dynamic and original entity in the realm of jazz, Spanish music, and the world music scene as a whole. Building on inherent compatibilities between jazz and flamenco, a generation of versatile Spanish musicians has synthesized the two genres in a wide variety of forms, creating in the process a coherent new idiom that can be regarded as a sort of mainstream flamenco jazz style. A few of these performers, such as pianist Chano Domínguez and wind player Jorge Pardo, have achieved international acclaim and become luminaries on the Euro-jazz scene. Indeed, flamenco jazz has become something of a minor bandwagon in some circles, with that label often being adopted, with or without rigor, as a commercial rubric to promote various sorts of productions (while conversely, some of the genre’s top performers are indifferent to the label 1). Meanwhile, however, as increasing numbers of gifted performers enter the field and cultivate genuine and substantial syntheses of flamenco and jazz, the new genre has come to merit scholarly attention for its inherent vitality, richness, and significance in the broader jazz world. -

Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar

Rethinking Tradition: Towards an Ethnomusicology of Contemporary Flamenco Guitar NAME: Francisco Javier Bethencourt Llobet FULL TITLE AND SUBJECT Doctor of Philosophy. Doctorate in Music. OF DEGREE PROGRAMME: School of Arts and Cultures. SCHOOL: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Newcastle University. SUPERVISOR: Dr. Nanette De Jong / Dr. Ian Biddle WORD COUNT: 82.794 FIRST SUBMISSION (VIVA): March 2011 FINAL SUBMISSION (TWO HARD COPIES): November 2011 Abstract: This thesis consists of four chapters, an introduction and a conclusion. It asks the question as to how contemporary guitarists have negotiated the relationship between tradition and modernity. In particular, the thesis uses primary fieldwork materials to question some of the assumptions made in more ‘literary’ approaches to flamenco of so-called flamencología . In particular, the thesis critiques attitudes to so-called flamenco authenticity in that tradition by bringing the voices of contemporary guitarists to bear on questions of belonging, home, and displacement. The conclusion, drawing on the author’s own experiences of playing and teaching flamenco in the North East of England, examines some of the ways in which flamenco can generate new and lasting communities of affiliation to the flamenco tradition and aesthetic. Declaration: I hereby certify that the attached research paper is wholly my own work, and that all quotations from primary and secondary sources have been acknowledged. Signed: Francisco Javier Bethencourt LLobet Date: 23 th November 2011 i Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank all of my supervisors, even those who advised me when my second supervisor became head of the ICMuS: thank you Nanette de Jong, Ian Biddle, and Vic Gammon. -

Downbeat.Com September 2010 U.K. £3.50

downbeat.com downbeat.com september 2010 2010 september £3.50 U.K. DownBeat esperanza spalDing // Danilo pérez // al Di Meola // Billy ChilDs // artie shaw septeMBer 2010 SEPTEMBER 2010 � Volume 77 – Number 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser AdVertisiNg sAles Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] offices 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] customer serVice 877-904-5299 [email protected] coNtributors Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, How- ard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer -

Paco De Lucía

Ralph Towner Poste Italiane S.p.A. – Spedizione in abbonamento postale – D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in L. 27/02/2004 n.46) art. 1, comma CN/BO Poste Italiane S.p.A. – Spedizione in abbonamento postale D.L. 353/2003 (conv. La fabulosa guitarra de PACO DE LUCÍA MARCUS EATON ISBN 978-889-8642-57-1 a proposito di Croz 9 788898 642571 CA1405 Strumenti: Rozawood, Eko EVO, Hermann Lap steel, Heart Sound Perlucens, Pre ESD e VDL editoriale ed Dedicato a Paco Confesso di essermi commosso più volte rileg- VCTNCEQPNCRTQHQPFKV´FKVWVVGSWGNNGEWNVWTGOWUKECNK gendo l’articolo dedicato a Paco de Lucía. Non sol- che basano la loro conoscenza sulla tradizione ora- tanto per il dolore, immenso e inevitabile, causato NGGRQRQNCTG%QOOQXGPVKCRRWPVQUQPQFCSWG- dalla morte di uno dei chitarristi in assoluto più im- sto punto di vista i racconti di de Lucía circa la sua portanti del Novecento. E per le tenere circostan- dedizione e i suoi sforzi per imparare, dagli spartiti, \GUGEQUÇUKRWÍFKTGKPEWKUKÂXGTKſECVCOGPVTG OWUKEJG VCPVQ COCVG EQOG SWGNNG FK FG (CNNC G KN IKQECXCCRCNNQPGEQPKNſINKQRKÔRKEEQNQ&KGIQKP Concierto de Aranjuez FK,QCSWÈP4QFTKIQ occasione di un periodo di riposo insieme alla fami- +PSWGUVQPWOGTQFGFKECVQC2CEQPQPCDDKCOQ glia sulle spiagge dello Yucatàn. Ma in particolare voluto far mancare altri articoli di spessore. Primo per le corde intime che Francesco Rampichini ha HTCVWVVKSWGNNQEQPUCETCVQC4CNRJ6QYPGTEJGEK saputo toccare nel suo ricordo, anche grazie a una ha incantati con l’intatta energia creativa della sua EGTVCEQPſFGP\CEJGÂTKWUEKVQCEQPSWKUVCTUKEQPKN musica in occasione della sua partecipazione a ITCPFGOCGUVTQCPFCNWUQſPFCKVGORKFGNNGTKRGVW- Madame Guitar dello scorso anno, sia come ospite te interviste raccolte nel corso della sua storica col- FGNNŏ+VCNKCP)WKVCTU6TKQEJGPGNNCUWCKPFKOGPVKECDKNG laborazione con la rivista Chitarre&GNTGUVQ(TCP- performance in solo. -

CLASSIC GUITAR JOURNAL Published by the Phllharmonic SOCIETY of GUITARISTS, L St

THE CLASSIC GUITAR JOURNAL Published by the PHlLHARMONIC SOCIETY OF GUITARISTS, l St. Dunstan's Road, London, W.6 • No. 37 JANUARY 1957 2/- EDITORIAL Presti. We know what is good, in the most precise terms, we have standards and they are very high- playing such as that of Segovia, Presti, Everybody likes to play guitar solos (or at least to try) and most of and Alirio Diaz is our touchstone. So clear is our vision that we do us have accumulated those little heaps of music that we like to think not want anything but the best on our professional platforms; not only we can play. The most striking feature of the guitar solo repertoire as is the second-best an affront to our critical intelligence, but it is a such is its sheer bulk-and though few if any of us will ever even see, downright disservice to the guitar and can do nothing to enhance its Jet alone come to terms with a great deal of it, it grows almost daily standing with other serious musicians. through the normal activity of publishers and guitar journals all over These thoughts have been with us for some time now, but recently the world. On the other hand the publication of music in which the guitar they were reinforced by the visit to London of a professional continental takes part in ensembles (and we include guitar duets under this heading) guitarist who came, armed with a small brochure filled with eulogistic hardly matches the growing interest in such activity. Many players are reviews from an assorted press, in search of recitals. -

May 2016 FREE

Issue 58 May 2016 FREE upporting ocal rts & erformers Last month ended on yet another sad musical note as Prince left this plane, if indeed he ever inhabited the same one as us mere mortals. Certainly not everyone's cup of Darjeeling but few could deny his supranatural talents whether in writing, playing, performing or inspiring; he was often cited as one of the most underrated guitarists, probably only though because he was so good at almost everything else. Tis a cliché but his like will certainly not be seen again: Sometimes It Snows In April indeed. MAY2016 On a brighter note April also saw a record-breaking (not literally hopefully) Record Store Day as local shops outdid themselves, despite some unfortunates queueing outside Rise in Worcester having to contend with snow flurries. The tills were SLAP MAGAZINE red hot though so we are told and business was more than brisk with no sign of the record (not 'vinyl' please) boom Unit 3a, Lowesmoor Wharf, slowing down any time soon. You can read and see much more Worcester WR1 2RS about what was an absolutely storming day, in Duncan Graves' Telephone: 01905 26660 review and photo spread on page 23. [email protected] And so we march into May (or it may still be March for all I know) somewhat trepidatiously: "Ne'er cast a clout til May is For advertising enquiries, please contact: out" goes the old farmers' saying; clout being yer coat not a [email protected] wallop! But the grass is ever growing as the festival season begins in earnest with The Beltane Bash, Cheltenham Jazz, EDITORIAL Mark Hogan - Editor Beat it!, Mello, Out To Grass, Wychwood, Breaking Bands, Winchcombe, Lechade, Tenbury and Lunar all imminent. -

Music 2016 ADDENDUM This Catalog Includes New Sheet Music, Songbooks, and Instructional Titles for 2016

Music 2016 HAL LEONARD ADDENDUM This catalog includes new sheet music, songbooks, and instructional titles for 2016. Please be sure to see our separate catalogs for new releases in Recording and Live Sound as well as Accessories, Instruments and Gifts. See the back cover of this catalog for a complete list of all available Hal Leonard Catalogs. 1153278 Guts.indd 1 12/14/15 4:15 PM 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sheet Music .........................................................3 Piano .................................................................53 Musicians Institute ............................................86 Fake Books ........................................................4 E-Z Play Today ...................................................68 Guitar Publications ............................................87 Personality .........................................................7 Organ ................................................................69 Bass Publications ............................................102 Songwriter Collections .......................................21 Accordion..........................................................70 Folk Publications .............................................104 Mixed Folios ......................................................23 Instrumental Publications ..................................71 Vocal Publications .............................................48 Berklee Press ....................................................85 INDEX: Accordion..........................................................70 -

Robert Trent – WPAC Concert Hall 7:30 P.M

Miami International GuitART Festival 2016 Production Personnel Festival Director: Mesut Özgen Events Manager: Nathalie Brenner Budget Coordinator: Britton Davis Marketing Coordinator: Michelle Vires CARTA Development Director: Lisa Merritt CARTA Administrative Director: Lilia Silverio-Minaya School of Music Office Manager: Cindy Mesa Technical Manager Paul Steinsland Technical Support: Carlos Dominguez SPECIAL THANKS TO Mark B. Rosenberg President, Florida International University Kenneth G. Furton Provost and Executive Vice President, FIU Brian Schriner Dean, FIU College of Architecture + the Arts Robert B. Dundas Director, FIU School of Music John Stuart Executive Director, Miami Beach Urban Studios James Webb Director, Stocker AstroScience Center Özgür Kıvanç Altan Consul General, Turkish Consulate General in Miami Serap Obabaş-Yiğit President, Florida Turkish American Association Carlos Molina President, Miami Classical Guitar Society A note to our audiences: ADDITIONAL THANKS TO Anneyra Espinosa Please keep your program Director, FIU Office of Financial Planning during the festival, as we Roberto Rodriguez have printed a finite President, Guitar Club at FIU number of festival program books. Adela M. Jover Facilities Scheduler, Graham University Center Thank you. Mike Comiskey General Manager, Barnes & Noble at FIU TO PURCHASE ADVANCE TICKETS ($2 lower than door prices), please visit wpac.fiu.edu or migf.org MIAMI INTERNATIONAL GUITART FESTIVAL 2016 WELCOME Welcome to the 2016 Miami International GuitART Festival, presented by the Florida International University School of Music at the Herbert and Nicole Wertheim Performing Arts Center. It is my honor and privilege to serve as Artistic Director of the MIGF inaugural edition, which has been a dream of mine for a long time. Since I came to Miami, where is a home to so many wonderfully talented guitar artists, we have been building a strong guitar program at the FIU School of Music with many outstanding students. -

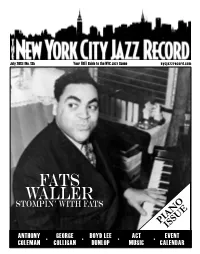

Stompin' with Fats

July 2013 | No. 135 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com FATS WALLER Stompin’ with fats O N E IA U P S IS ANTHONY • GEORGE • BOYD LEE • ACT • EVENT COLEMAN COLLIGAN DUNLOP MUSIC CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK FEATURED ARTISTS / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 RESIDENCIES / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 Mondays July 1, 15, 29 Friday & Saturday July 5 & 6 Wednesday July 3 Jason marshall Big Band Papa John DeFrancesco Buster Williams sextet Mondays July 8, 22 Jean Baylor (vox) • Mark Gross (sax) • Paul Bollenback (g) • George Colligan (p) • Lenny White (dr) Wednesday July 10 Captain Black Big Band Brian Charette sextet Tuesdays July 2, 9, 23, 30 Friday & Saturday July 12 & 13 mike leDonne Groover Quartet Wednesday July 17 Eric Alexander (sax) • Peter Bernstein (g) • Joe Farnsworth (dr) eriC alexaNder QuiNtet Pucho & his latin soul Brothers Jim Rotondi (tp) • Harold Mabern (p) • John Webber (b) Thursdays July 4, 11, 18, 25 Joe Farnsworth (dr) Wednesday July 24 Gregory Generet George Burton Quartet Sundays July 7, 28 Friday & Saturday July 19 & 20 saron Crenshaw Band BruCe Barth Quartet Wednesday July 31 Steve Nelson (vibes) teri roiger Quintet LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES Mon the smoke Jam session Friday & Saturday July 26 & 27 Sunday July 14 JavoN JaCksoN Quartet milton suggs sextet Tue milton suggs Quartet Wed Brianna thomas Quartet Orrin Evans (p) • Santi DeBriano (b) • Jonathan Barber (dr) Sunday July 21 Cynthia holiday Thr Nickel and Dime oPs Friday & Saturday August 2 & 3 Fri Patience higgins Quartet mark Gross QuiNtet Sundays Sat Johnny o’Neal & Friends Jazz Brunch Sun roxy Coss Quartet With vocalist annette st. -

Catalogue CD Jazz

DISCOTHEQUE CAESUG CAMPUS CATALOGUE DES DISQUES COMPACTS J A Z Z CLASSEMENT PAR ORDRE ALPHABETIQUE ABERCROMBIE John : A - Anachronic J 37 * Gateway ABOU-KHALIL Rabib : J 240 * Al-Jadida J 453 * The cactus of knowledge J 474 * Il sospiro J 638 * Journey to the centre of an egg avec Joachim Kühn J 322 * The Sultan's Picnic J 498 * Yara (Musique du film) ACHIARY Benat : J 227 * Lili Purprea ACOUSTIC ALCHEMY : J 451 * Arcan'um ADDERLEY Cannonball : J 68 * Somethin' else AGOSSI Mina : J 646 * Well you needn't ALLEN Geri : J 128 * In the year of the dragon ALLISON Luther : J 234 * Hand me dowm my moonshine V 143 * Here I come J 594 * Richman AMSALLEM Franck : J 527 * Summertimes ANACHRONIC JAZZ BAND : J 220-1 * Enregistrements complets ANDERSON Ernestine : Anderson - A J 450 * Live from Concord to London ARIOLI Susie : J 681 * Live au festival de Montréal (avec DVD) ARMSTRONG Louis : J 226 * Ella and Louis J 1 * Ella and Louis again J 230 * The Hot Fives J 551 * Hot Five and Hot Seven J 228 * Louis and the Good Book J 53 * New Orleans J 22 * Porgy and Bess J 185 * Année 1923 ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO : J 591 * 1969 – 1970 J 38 * Full force AVITABILE Franck : J 675 * Short stories AZZOLA Marcel : J 683 * 3 temps pour bien faire (avec Marc Fosset & Patrice Caratini BAKER Chet : B - Bibb J 118) * Broken Wing J 160-1 * Le dernier grand concert J 595 * Peace J 74 * The touch of your lips BARBER Chris : J 181 * Fifty cents.(avec Louis Jordan) BARBER Patricia : J 672 * Mythologies BARBIERI Gato : J 596 * Apasionado BARRON Kenny : J 625 * Kenny Barron -

18 Th and 19 Th Century Who Had an Impact on Later Developments in Jazz Guitar

The development of the Electric Jazz Guitar in the 20 th century – by Pebber Brown One of the areas that is historically very important but sorely missing from any music texts, is that of the history of the jazz guitar and its players. In this essay, I will explore some of its early origins as an instrument and briefly look at some of the significant early guitar players of the 18 th and 19 th century who had an impact on later developments in jazz guitar. Moving into the early part of the 20 th century, I will also explore some of the influential non-classical guitarists who influenced the acceptance of the guitar as a viable jazz instrument, and lastly I will explore the importance of the invention of the electric guitar an look at some of the less well known but very important jazz guitarists of the 20 th century. Some insight into the origins of the guitar The guitar was invented many centuries ago in Spain as a predecessor of older Middle-Eastern stringed instruments such as the Zither, and the Lyre. The first guitars had less strings on them and were called "Chitarra." These instruments were played up until the 17th century when the more modern "Guitarra" was invented in Spain. The Guitarra later became the "Guitar," and it made its way to Northern Europe and in England and the Netherlands they created their own version of it called the Lute. Lutes are most called "Baroque" lutes pertaining to the music played on them during the Baroque period. -

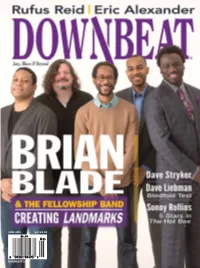

Downbeat.Com June 2014 U.K. £3.50

JUNE 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM JUNE 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom