A Survey of the Keyboard Prelude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003 The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire by Bonny Kathleen Winston, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2003 Dedication This dissertation would not have been completed without all of the love and support from professors, family, and friends. To all of my dissertation committee for their support and help, especially John Geringer for his endless patience, Betty Mallard for her constant inspiration, and Martha Hilley for her underlying encouragement in all that I have done. A special thanks to my family, who have been the backbone of my music growth from childhood. To my parents, who have provided unwavering support, and to my five brothers, who endured countless hours of before-school practice time when the piano was still in the living room. Finally, a special thanks to my hall-mate friends in the school of music for helping me celebrate each milestone of this research project with laughter and encouragement and for showing me that graduate school really can make one climb the walls in MBE. The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire Publication No. ________________ Bonny Kathleen Winston, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisor: John M. Geringer The purpose of this dissertation was to create an on-line database for intermediate piano repertoire selection. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 © Copyright by Ryan Isao Rowen 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transcending Imagination; Or, An Approach to Music and Symbolism during the Russian Silver Age by Ryan Isao Rowen Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Chair The Silver Age has long been considered one of the most vibrant artistic movements in Russian history. Due to sweeping changes that were occurring across Russia, culminating in the 1917 Revolution, the apocalyptic sentiments of the general populace caused many intellectuals and artists to turn towards esotericism and occult thought. With this, there was an increased interest in transcendentalism, and art was becoming much more abstract. The tenets of the Russian Symbolist movement epitomized this trend. Poets and philosophers, such as Vladimir Solovyov, Andrei Bely, and Vyacheslav Ivanov, theorized about the spiritual aspects of words and music. It was music, however, that was singled out as possessing transcendental properties. In recent decades, there has been a surge in scholarly work devoted to the transcendent strain in Russian Symbolism. The end of the Cold War has brought renewed interest in trying to understand such an enigmatic period in Russian culture. While much scholarship has been ii devoted to Symbolist poetry, there has been surprisingly very little work devoted to understanding how the soundscape of music works within the sphere of Symbolism. -

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-Year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina Hello everyone, my name is Qiwen Wan. I am a first-year doctoral student in piano pedagogy major at the University of South Carolina. I am really glad to be here and thanks to SCMTA to allow me to present online under this circumstance. The topiC of my lightning talk is 5 stages for teaChing Alberto Ginastera's Twelve AmeriCan Preludes. First, please let me introduce this colleCtion. Twelve AmeriCan Preludes is composed by Alberto Ginastera, who is known as one of the most important South AmeriCan composers of the 20th century. It was published in two volumes in 1944. In this colleCtion, there are 12 short piano pieCes eaCh about one minute in length. Every prelude has a title, tempo and metronome marking, and eaCh presents a different charaCter or purpose for study. There are two pieCes that focus on a speCifiC teChnique, titled Accents, and Octaves. No. 5 and 12 are titled with PentatoniC Minor and Major Modes. Triste, Creole Dance, Vidala, and Pastorale display folk influences. The remaining four pieCes pay tribute to other 20th-Century AmeriCan composers. This set of preludes is an attraCtive output for piano that skillfully combines folk Argentine rhythms and Colors with modern composing teChniques. Twelve American Preludes is a great contemporary composition for late-intermediate to early-advanced students. In The Pianist’s Guide to Standard Teaching and Performing Literature, Dr. Jane Magrath uses a 10-level system to list the pieCes from this colleCtion in different levels. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations In

MYSTIC CHORD HARMONIC AND LIGHT TRANSFORMATIONS IN ALEXANDER SCRIABIN’S PROMETHEUS by TYLER MATTHEW SECOR A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Tyler Matthew Secor Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Jack Boss Chair Dr. Stephen Rodgers Member Dr. Frank Diaz Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2013 ii © 2013 Tyler Matthew Secor iii THESIS ABSTRACT Tyler Matthew Secor Master of Arts School of Music and Dance September 2013 Title: Mystic Chord Harmonic and Light Transformations in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus This thesis seeks to explore the voice leading parsimony, bass motion, and chromatic extensions present in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus. Voice leading will be explored using Neo-Riemannian type transformations followed by network diagrams to track the mystic chord movement throughout the symphony. Bass motion and chromatic extensions are explored by expanding the current notion of how the luce voices function in outlining and dictating the harmonic motion. Syneathesia -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

Ballet Notes the Seagull March 21 – 25, 2012

Ballet Notes The SeagUll March 21 – 25, 2012 Aleksandar Antonijevic and Sonia Rodriguez as Trigorin and Nina. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann. Orchestra Violins Trumpets Benjamin Bowman Richard Sandals, Principal Concertmaster Mark Dharmaratnam Lynn KUo, Robert WeymoUth Assistant Concertmaster Trombones DominiqUe Laplante, David Archer, Principal Principal Second Violin Robert FergUson James Aylesworth David Pell, Bass Trombone Jennie Baccante Csaba Ko czó Tuba Sheldon Grabke Sasha Johnson, Principal Xiao Grabke • Nancy Kershaw Harp Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk LUcie Parent, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., FoUnder Yakov Lerner Timpany George Crum, MUsic Director EmeritUs Jayne Maddison Michael Perry, Principal Ron Mah Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Aya Miyagawa Percussion Mark MazUr, Acting Artistic Director ExecUtive Director Wendy Rogers Filip Tomov Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Joanna Zabrowarna Kristofer Maddigan MUsic Director and Artist-in-Residence PaUl ZevenhUizen Orchestra Personnel Principal CondUctor Violas Manager and Music Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Angela RUdden, Principal Administrator Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, • Theresa RUdolph Koczó, Jean Verch YOU dance / Ballet Master Assistant Principal Assistant Orchestra Valerie KUinka Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Personnel Manager Johann Lotter Raymond Tizzard Senior Ballet Master Richardson Beverley Spotton Senior Ballet Mistress • Larry Toman Librarian LUcie Parent Aleksandar Antonijevic, GUillaUme Côté, Cellos Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, Zdenek Konvalina*, -

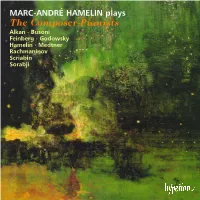

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN Plays the Composer-Pianists Alkan

MARC-ANDRÉ HAMELIN plays The Composer-Pianists Alkan . Busoni Feinberg . Godowsky Hamelin . Medtner Rachmaninov Scriabin Sorabji HE RELATION between musical effect and the technical ‘encore’ repertoire; less convincingly as regards the latter half means necessary for its creation or recreation is apt to of a recital, which at one time might have been entirely Tbe one of opposites. The ‘Representation of Chaos’ with devoted to the type of confection indicated above. However, it which Haydn embarked on The Creation, for example, could can be said that the present offers the best of all liberal worlds, not have succeeded without a conspicuously well ordered in which deeply serious artists may leaven but not demean the compositional technique, nor could the percussion- and intellectual and spiritual weight of their mainstream reper- timpani-based anarchy of Nielsen’s Fourth and Fifth toire by restoring to public attention the full variety and zest of Symphonies or, indeed, the ‘controlled chance’ of more a once discredited milieu. In this connection the abstract recent, aleatory trends. A true chaos of means leads only to nature and importance of ‘pianism’ itself should be empha- incoherence, whereas an intended one of expressive ends may sized: for the serious performing artist the purely physical, be likened to the birth of a universe: explosive, precipitate, callisthenic dimension in Tausig, Rosenthal, Schulz-Evler, seemingly beyond all elemental control, and yet achieved with Scharwenka, Hoffman, Godowsky and others illumines the the pinprick accuracy of some infinitely magnified snowflake, nature of the instrument, and of the art itself, in myriad and defying our later scrutiny to find in it mere accident rather idiosyncratic ways. -

Mengjiao Yan Phd Thesis.Pdf

The University of Sheffield Stravinsky’s piano works from three distinct periods: aspects of performance and latitude of interpretation Mengjiao Yan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music The University of Sheffield Jessop Building, Sheffield, S3 7RD, UK September 2019 1 Abstract This research project focuses on the piano works of Igor Stravinsky. This performance- orientated approach and analysis aims to offer useful insights into how to interpret and make informed decisions regarding his piano music. The focus is on three piano works: Piano Sonata in F-Sharp Minor (1904), Serenade in A (1925), Movements for Piano and Orchestra (1958–59). It identifies the key factors which influenced his works and his compositional process. The aims are to provide an informed approach to his piano works, which are generally considered difficult and challenging pieces to perform convincingly. In this way, it is possible to offer insights which could help performers fully understand his works and apply this knowledge to performance. The study also explores aspects of latitude in interpreting his works and how to approach the notated scores. The methods used in the study include document analysis, analysis of music score, recording and interview data. The interview participants were carefully selected professional pianists who are considered experts in their field and, therefore, authorities on Stravinsky's piano works. The findings of the results reveal the complex and multi-faceted nature of Stravinsky’s piano music. The research highlights both the intrinsic differences in the stylistic features of the three pieces, as well as similarities and differences regarding Stravinsky’s compositional approach. -

Summary of Dissertation Recitals by Zixiang Wang

Summary of Dissertation Recitals by Zixiang Wang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Arthur Greene, Chair Professor James Borders Lecturer Amy I-Lin Cheng Professor Logan Skelton Associate Professor Gregory Wakefield Zixiang Wang [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2601-5804 © Zixiang Wang 2020 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my grandmother. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my teacher, Professor Arthur Greene, for his tremendous support and excellent guidance in this journey. I also want to thank my dissertation committee for their generous help and encouragement. Finally, I want to thank my parents for their selfless love. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF EXAMPLES v ABSTRACT vi RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 5 Recital 2 Program 5 Recital 2 Program Notes 6 RECITAL 3 9 Recital 3 Program 9 Recital 3 Lecture Script 10 Biography 21 iv LIST OF EXAMPLES EXAMPLE 1.a Scriabin Sonata No. 1 1st movement, m. 1 Three-Note-Scale Motif 14 1.b Scriabin Sonata No. 1 4th movement, mm. 1-2 Funeral March Motif 14 2 Scriabin Sonata No. 1 1st movement, mm. 1-2 15 3.a Chopin Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 31, mm. 1-9 17 3.b Scriabin Sonata No. 1, 3rd movement, m. 13 17 4 Scriabin Sonata No. 1, 3rd movement, mm. 77-86 18 5 Scriabin Sonata No.