COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Activity Sheet

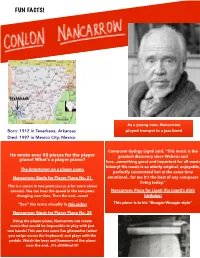

FUN FACTS! As a young man, Nancarrow Born: 1912 in Texarkana, Arkansas played trumpet in a jazz band Died: 1997 in Mexico City, Mexico Composer György Ligeti said, “This music is the He wrote over 50 pieces for the player greatest discovery since Webern and piano! What’s a player piano? Ives...something great and important for all music history! His music is so utterly original, enjoyable, The Entertainer on a player piano perfectly constructed but at the same time Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 21 emotional...for me it’s the best of any composer living today.” This is a canon in two parts (see p. 6 for more about canons). You can hear the speed in the two parts Nancarrow: Piece for Ligeti (for Ligeti’s 65th changing over time. Then the end...wow! birthday) “See” the score visually in this video This piece is in his “Boogie-Woogie style” Nancarrow: Study for Player Piano No. 25 Using the player piano, Nancarrow can create music that would be impossible to play with just two hands! This one has some fun glissandos (when you swipe across the keyboard) and plays with the pedals. Watch the keys and hammers of the piano near the end...it’s aliiiiiiive!!!!! 1 FUN FACTS! Population: 130 million Capital: Mexico City (Pop: 9 million) Languages: Spanish and over 60 indigenous languages Currency: Peso Highest Peak: Pico de Orizaba volcano, 18,491 ft Flag: Legend says that the Aztecs settled and built their capital city (Tenochtitlan, Mexico City today) on the spot where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a snake. -

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003

Copyright by Bonny Kathleen Winston 2003 The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire by Bonny Kathleen Winston, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2003 Dedication This dissertation would not have been completed without all of the love and support from professors, family, and friends. To all of my dissertation committee for their support and help, especially John Geringer for his endless patience, Betty Mallard for her constant inspiration, and Martha Hilley for her underlying encouragement in all that I have done. A special thanks to my family, who have been the backbone of my music growth from childhood. To my parents, who have provided unwavering support, and to my five brothers, who endured countless hours of before-school practice time when the piano was still in the living room. Finally, a special thanks to my hall-mate friends in the school of music for helping me celebrate each milestone of this research project with laughter and encouragement and for showing me that graduate school really can make one climb the walls in MBE. The Development of a Multimedia Web Database for the Selection of 20th Century Intermediate Piano Repertoire Publication No. ________________ Bonny Kathleen Winston, D.M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2003 Supervisor: John M. Geringer The purpose of this dissertation was to create an on-line database for intermediate piano repertoire selection. -

Record Group 6

Special Collections in Performing Arts MUSIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION ARCHIVES Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library Record Group VI. Notes University of Maryland, College Park, MD Finding Aid by Melissa E. Wertheimer, MLA Archivist, 2018 MUSIC LIBRARY ASSOCIATION ARCHIVES: COLLECTION SUMMARY INFORMATION Finding Aid created with Describing Archives: A Content Standard, 2nd Edition Repository Special Collections in Performing Arts, Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library, Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 Creator Music Library Association Title Music Library Association Archives Date 1931 – 2017 [ongoing] Extent Approximately 300 linear feet of paper records; 5GB of digital materials; sound recordings Languages English with additional documents in French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. Preferred Citation Music Library Association Archives, Special Collections in Performing Arts, University of Maryland, College Park, MD COLLECTION SCOPE & CONTENTS The Music Library Association Archives contains the official records of the Music Library Association (MLA) that document the history, activities, and publications of the organization since its founding in 1931. MLA is the professional association for music libraries and librarianship in the United States with the mission to provide a professional forum for librarians, archivists, and others who support and preserve musical heritage. Formats in the records include manuscripts, financial ledgers, printed publications, sound recordings, oral histories, photographs, scrapbooks, microfilm, realia, born-digital files, musical scores, and artwork. The collection also contains records of select current and former regional chapters, including the Atlantic, Greater New York, Mountain-Plains, and New England Chapters. Records of the California, Midwest, New York State-Ontario, Pacific Northwest, Southeast, and Texas Chapters are housed in repositories within their geographic areas. -

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-Year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina

5 Stages for Teaching Alberto Ginastera's Twelve American Preludes Qiwen Wan First-year DMA in Piano Pedagogy University of South Carolina Hello everyone, my name is Qiwen Wan. I am a first-year doctoral student in piano pedagogy major at the University of South Carolina. I am really glad to be here and thanks to SCMTA to allow me to present online under this circumstance. The topiC of my lightning talk is 5 stages for teaChing Alberto Ginastera's Twelve AmeriCan Preludes. First, please let me introduce this colleCtion. Twelve AmeriCan Preludes is composed by Alberto Ginastera, who is known as one of the most important South AmeriCan composers of the 20th century. It was published in two volumes in 1944. In this colleCtion, there are 12 short piano pieCes eaCh about one minute in length. Every prelude has a title, tempo and metronome marking, and eaCh presents a different charaCter or purpose for study. There are two pieCes that focus on a speCifiC teChnique, titled Accents, and Octaves. No. 5 and 12 are titled with PentatoniC Minor and Major Modes. Triste, Creole Dance, Vidala, and Pastorale display folk influences. The remaining four pieCes pay tribute to other 20th-Century AmeriCan composers. This set of preludes is an attraCtive output for piano that skillfully combines folk Argentine rhythms and Colors with modern composing teChniques. Twelve American Preludes is a great contemporary composition for late-intermediate to early-advanced students. In The Pianist’s Guide to Standard Teaching and Performing Literature, Dr. Jane Magrath uses a 10-level system to list the pieCes from this colleCtion in different levels. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

The Function of Music in Sound Film

THE FUNCTION OF MUSIC IN SOUND FILM By MARIAN HANNAH WINTER o MANY the most interesting domain of functional music is the sound film, yet the literature on it includes only one major work—Kurt London's "Film Music" (1936), a general history that contains much useful information, but unfortunately omits vital material on French and German avant-garde film music as well as on film music of the Russians and Americans. Carlos Chavez provides a stimulating forecast of sound-film possibilities in "Toward a New Music" (1937). Two short chapters by V. I. Pudovkin in his "Film Technique" (1933) are brilliant theoretical treatises by one of the foremost figures in cinema. There is an ex- tensive periodical literature, ranging from considered expositions of the composer's function in film production to brief cultist mani- festos. Early movies were essentially action in a simplified, super- heroic style. For these films an emotional index of familiar music was compiled by the lone pianist who was musical director and performer. As motion-picture output expanded, demands on the pianist became more complex; a logical development was the com- pilation of musical themes for love, grief, hate, pursuit, and other cinematic fundamentals, in a volume from which the pianist might assemble any accompaniment, supplying a few modulations for transition from one theme to another. Most notable of the collec- tions was the Kinotek of Giuseppe Becce: A standard work of the kind in the United States was Erno Rapee's "Motion Picture Moods". During the early years of motion pictures in America few original film scores were composed: D. -

Collective Difference: the Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Collective Difference: The Pan-American Association of Composers and Pan- American Ideology in Music, 1925-1945 Stephanie N. Stallings Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC COLLECTIVE DIFFERENCE: THE PAN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF COMPOSERS AND PAN-AMERICAN IDEOLOGY IN MUSIC, 1925-1945 By STEPHANIE N. STALLINGS A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stephanie N. Stallings All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephanie N. Stallings defended on April 20, 2009. ______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Brewer Committee Member ______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my warmest thanks to my dissertation advisor, Denise Von Glahn. Without her excellent guidance, steadfast moral support, thoughtfulness, and creativity, this dissertation never would have come to fruition. I am also grateful to the rest of my dissertation committee, Charles Brewer, Evan Jones, and Douglass Seaton, for their wisdom. Similarly, each member of the Musicology faculty at Florida State University has provided me with a different model for scholarly excellence in “capital M Musicology.” The FSU Society for Musicology has been a wonderful support system throughout my tenure at Florida State. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

![Minna Lederman Daniel Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7275/minna-lederman-daniel-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-1067275.webp)

Minna Lederman Daniel Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Minna Lederman Daniel Collection Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2009 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2009543859 Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2009 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu009006 Latest revision: 2010 March Collection Summary Title: Minna Lederman Daniel Collection Span Dates: 1896-1993 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1990) Call No.: ML31.L43 Creator: Lederman, Minna Extent: circa 20,000 items ; 22 containers ; 11 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The collection contains correspondence, financial and legal papers, writings, clippings, and photographs belonging to Minna Lederman Daniel, an editor and writer about music and dance, and a major influence on 20th century music. She was a founding member of the League of Composers, a group of musicians and proponents of modern music. She helped launch the League’s magazine, The League of Composers’ Review (later called Modern Music), which was the first American journal to manifest an interest in contemporary composers. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Cage, John--Correspondence. Cage, John. Carter, Elliott, 1908- --Correspondence. Copland, Aaron, 1900-1990--Correspondence. Copland, Aaron, 1900-1990. Cunningham, Merce--Correspondence. Denby, Edwin, 1903-1983--Correspondence.