Proving Liability in Slip and Fall Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP 2015

© Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP 2015 Everence Stewardship University Session A3 J. Doe v. Church Presented by GKH Attorney Peter J. Kraybill March 7, 2015 © Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP 2015 J. Doe v. Church Churches are not as “special” to outsiders, whether those outsiders are • cyber squatters • copyright holders • banks or • slip-and-fall victims Churches often will be treated as equal to businesses or other “legal entities” for purposes of • contract law • trademarks • copyrights and • negligence, among others. How can churches be protective and proactive when engaging with the world? Legal Threats State action versus Private action (government enforcement compared to civil litigation) State Action What about the government going after a church? US Constitution - Bill of Rights - First Amendment - Freedom of Religion - "Free exercise” clause: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof… http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/free_exercise_clause Free Exercise Clause The Free Exercise Clause reserves the right of American citizens to accept any religious belief and engage in religious rituals. The clause protects not just those beliefs but actions taken for those beliefs. Specifically, this allows religious exemption from at least some generally applicable laws, i.e. violation of laws is permitted, as long as that violation was for religious reasons. In 1940, the Supreme Court held in Cantwell v. Connecticut that, due to the Fourteenth Amendment, the Free Exercise Clause is enforceable against state and local governments. http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/free_exercise_clause Extra credit: Famous example of the Amish using the Free Exercise Clause? Wisconsin v. -

The Slip and Fall of the California Legislature in the Classification of Personal Injury Damages at Divorce and Death

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Publications Faculty Scholarship Summer 2009 The liS p and Fall of the California Legislature in the Classification of Personal Injury Damages At Divorce and Death Helen Y. Chang Golden Gate University - San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation 1 Estate Plan. & Comm. Prop. L. J. 345 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SLIP AND FALL OF THE CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE IN THE CLASSIFICATION OF PERSONAL INJURY DAMAGES AT DIVORCE AND DEATH by Helen Y. Chang* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 345 II. CALIFORNIA'S HISTORICAL TREATMENT OF PERSONAL INJURY D AM AGES .......................................................................................... 347 A. No-Fault Divorce and the Principleof Equality ...................... 351 B. Problems with the CurrentCalifornia Law .............................. 354 1. The Cause ofAction 'Arises'PerFamily Code Section 2 603 ...................................................................................355 2. Division of PersonalInjury Damages at Divorce.............. 358 3. The Classification of PersonalInjury Damages -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

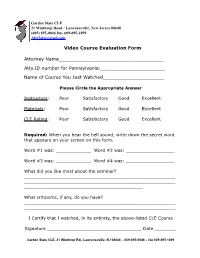

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

SCC File No. 39108 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA (ON APPEAL from the COURT of APPEAL for BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: CITY OF

SCC File No. 39108 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: CITY OF NELSON APPLICANT (Respondent) AND: TARYN JOY MARCHI RESPONDENT (Appellant) ______________________________________________ MEMORANDUM OF ARUMENT OF THE RESPONDENT (Pursuant to Rule 27 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) ______________________________________________ DAROUX LAW CORPORATION MICHAEL J. SOBKIN 1590 Bay Avenue 33 Somerset Street West Trail, B.C. V1R 4B3 Ottawa, ON K2P 0J8 Tel: (250) 368-8233 Tel: (613) 282-1712 Fax: (800) 218-3140 Fax: (613) 288-2896 Danielle K. Daroux Michael J. Sobkin Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent, Taryn Joy Marchi Agent for Counsel for the Respondent MURPHY BATTISTA LLP #2020 - 650 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6B 4N7 Tel: (604) 683-9621 Fax: (604) 683-5084 Joseph E. Murphy, Q.C. Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent, Taryn Joy Marchi ALLEN / MCMILLAN LITIGATION COUNSEL #1550 – 1185 West Georgia Street Vancouver, B.C. V6E 4E6 Tel: (604) 569-2652 Fax: (604) 628-3832 Greg J. Allen Tele: (604) 282-3982 / Email: [email protected] Liam Babbitt Tel: (604) 282-3988 / Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Applicant, City of Nelson 1 PART I – OVERVIEW AND STATEMENT OF FACTS A. Overview 1. The applicant City of Nelson (“City”) submits that leave should be granted because there is lingering confusion as to the difference between policy and operational decisions in cases of public authority liability in tort. It cites four decisions in support of this proposition. None of those cases demonstrate any confusion on the part of the lower courts. -

When the Bough Breaks: a Proposal for Georgia Slip and Fall Law After Alterman Foods, Inc. V. Ligon Daniel W

Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law Volume 55 January 1999 When the Bough Breaks: A Proposal for Georgia Slip and Fall Law After Alterman Foods, Inc. v. Ligon Daniel W. Champney Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel W. Champney, When the Bough Breaks: A Proposal for Georgia Slip and Fall Law After Alterman Foods, Inc. v. Ligon, 55 Wash. U. J. Urb. & Contemp. L. 073 (1999) Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_urbanlaw/vol55/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Law Annual ; Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN THE BOUGH BREAKS: A PROPOSAL FOR GEORGIA SLIP AND FALL LAW AFTER ALTERMAN FOODS, INC. V LIGON INTRODUCTION Before the Georgia Supreme Court's recent decision in Robinson v. Kroger Co.' ("Robinson"), the authors of a yearly survey of Georgia tort law succinctly described the status of the subset of commercial premises liability law known as slip-and-fal 2 cases by stating: "Something is fundamentally wrong with the appellate standard of review for slip and fall cases in Georgia.",3 The problems 1. 493 S.E.2d 403 (Ga. 1997) (reexamining Georgia's slip-and-fall law for the first time since Barentine v. Kroger Co., 443 S.E.2d 485 (Ga. -

State of Wyoming Retail and Hospitality Compendium of Law

STATE OF WYOMING RETAIL AND HOSPITALITY COMPENDIUM OF LAW Prepared by Keith J. Dodson and Erica R. Day Williams, Porter, Day & Neville, P.C. 159 North Wolcott, Suite 400 Casper, WY 82601 (307) 265-0700 www.wpdn.net 2021 Retail, Restaurant, and Hospitality Guide to Wyoming Premises Liability Introduction 1 Wyoming Court Systems 2 A. The Wyoming State Court System 2 B. The Federal District Court for the District of Wyoming 2 Negligence 3 A. General Negligence Principles 3 B. Elements of a Cause of Action of Negligence 4 1. Notice 4 2. Assumption of Risk 5 Specific Examples of Negligence Claims 6 A. “Slip and Fall” Cases 6 1. Snow and Ice – Natural Accumulation 6 2. Slippery Surfaces 7 3. Defenses 9 B. Off Premises Hazards 12 C. Liability for Violent Crime 12 1. Tavern Keepers Liability for Violent Crime 13 2. Defenses 14 D. Claims Arising from the Wrongful Prevention of Thefts 15 1. False Imprisonment 15 2. Malicious Prosecution and Abuse of Process 16 3. Defamation 17 4. Negligent Hiring, Retention, or Supervision of Employees 18 5. Shopkeeper Immunity 18 6. Food Poisoning 19 E. Construction-Related Accidents 20 Indemnification and Insurance – Procurement Agreement 21 A. Indemnification 21 B. Insurance Procurement Agreements 23 C. Duty to Defend 23 Damages 24 A. Compensatory Damages 24 B. Collateral Source 25 C. Medical Damages (Billed v. Paid) 25 D. Nominal Damages 26 E. Punitive Damages 26 F. Wrongful Death and Survivorship Actions 27 1. Wrongful Death Actions 27 2. Survivorship Actions 28 Dram Shop Actions 28 A. Dram Shop Act 28 Introduction As our communities change and grow, retail stores, restaurants, hotels, and shopping centers have become new social centers. -

Retailer's Guide to New York Premises Liability

U STATE OF NEW YORK RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Prepared by Kenneth M. Alweis Stefan A. Borovina Goldberg Segalla LLP Email: [email protected] [email protected] www.goldbergsegalla.com 2014 USLAW Retail Compendium of Law Retail, Restaurant, and Hospitality Guide to New York Premises Liability Introduction 1 A. The New York State Court System 2 B. New York Federal Courts 2 Negligence 3 A. General Negligence Principles 3 B. Elements of a Cause of Action of Negligence 4 1. Creation of the Dangerous Condition 4 2. Actual Notice 4 3. Constructive Notice 5 C. The “Out of Possession Landlord” 5 D. Assumption of Risk 6 Examples of Negligence Claims 8 A. “Slip and Fall” Type Cases 8 1. Snow and Ice – “The Storm in Progress” Doctrine 8 2. “Black Ice” 9 3. Snow Removal Contractors 10 4. Slippery Surfaces – Cleaner, Polish, and Was 10 5. Defenses 10 a. Plaintiff Failed to Establish the Existence of a Defective Conditions 11 b. Trivial Defect 11 c. Open and Obvious Defects 12 B. Liability for Violent Crime 14 1. Control 14 2. Foreseeability 14 3. Joint and Several Liability 15 4, Security Contractors 16 5. Defenses 16 C. Claims Arising From the Wrongful Prevention of Thefts 19 1. False Arrest and Imprisonment 19 2. Malicious Prosecution 20 3. Defamation 21 4. Negligent Hiring, Retention, or Supervision of Employees 21 5. Shopkeeper Immunity 21 a. General Business Law §218 22 D. Food Poisoning 24 E. Construction-Related Accidents (New York Labor Law) 24 1. Labor Law §200 24 2. Labor Law §240(1) 25 a. -

PERSONAL INJURY LAW a Guide for Victims

LOUISIANA PERSONAL INJURY LAW A Guide for Victims Chad Dudley, Steven DeBosier, James Peltier, Jr. LOUISIANA PERSONAL INJURY A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR VICTIMS First Edition CHAD DUDLEY · STEVEN DEBOSIER · JAMES PELTIER Page 1 of 117 LOUISIANA PERSONAL INJURY A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR VICTIMS First Edition CHAD DUDLEY · STEVEN DEBOSIER · JAMES PELTIER Page 2 of 117 COPYRIGHT NOTICE © 2018 Dudley DeBosier® All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Dudley DeBosier®. For more information, please contact: Dudley DeBosier Injury Lawyers 1075 Government Street Baton Rouge, LA 70802 Page 3 of 117 DISCLAIMER The purpose of this book is not to give legal advice. Unless you have agreed to hire our law firm and we have agreed to represent you, our law firm does not represent you and will take no action on your behalf. Should you have any legal questions or concerns, we recommend that you contact your attorney and discuss the specifics of your case with them immediately. Please be aware that there are often deadlines that may apply to your claim, and therefore, it is important to act quickly! In the event you do not currently have legal representation and would like to set up a free consultation with an attorney at our firm, you may call our toll-free number 800-300-8300 or visit our website www.dudleydebosier.com to set up an appointment. Page 4 of 117 It is important to know that one attorney may act differently from another, but this does not mean that one is right and the other is wrong. -

INDIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol

XVII. Torts Judith T. Kirtland* A. Negligence 1. Duty.— In Rossow v. Jones,^ the court of appeals affirmed a judgment entered for a tenant and against his landlord for personal injuries arising from the tenant's slip and fall in his apartment house. The accident occurred on a common stairway over which the landlord exercised control. At the time of the accident, the steps were covered with snow and ice. For the purposes of this Survey, the most important issue con- sidered by the court was the question of the landlord's duty to his tenants. Specifically, the court's opinion focused on the 1882 Indiana Supreme Court decision of Purcell v. English,^ in which a tenant fell to the ground from a snow and ice covered common stairway when a rotten and loosened railing gave way. In that case, the supreme court affirmed a verdict directed against the tenant and stated that " when a common stairway 'is rendered unsafe by temporary causes, such as the accumulation of snow and ice, the landlord is not liable to the tenant who uses such stairway with full knowledge of its dangerous condition,' "^ unless the landlord has contracted to repair the premises. The Rossow court contrasted the Purcell decision with that of the court of appeals in LaPlante v. LaZear,^ in which a tenant recovered for personal injuries caused by a latent defect in a step. Purcell was distinguished on the grounds that it concerned only a tem- porary covering of snow and because that opinion had specifically excluded a latent defect from the scope of its holding.'' The LaPlante court, however, had specifically held that a landlord did have a duty to use reasonable care to maintain the common areas over which he maintained control.^ The court reaffirmed the LaPlante holding as to the landlord's duty to maintain the common areas under his control and then proceeded to implicitly overrule the Purcell decision by *Member of the Law Firm of Lewis, Bowman, St. -

Slip & Fall Claim

Risk Control General Liability - Slip & Fall Claim Kit Let’s face it, a slip or fall can happen anywhere, at any time and to anyone. So it’s critical that your business has a clear and concise plan to assist you in the process. Each year, over 8 million people are sent to hospital emergency rooms as the result of slip and fall accidents (www.cdc.gov). According to CNA claim data, the industries that typically experience a higher frequency of slip and fall incidents are Real Estate, Retail, Healthcare and Professional Services. Accidental deaths resulting from slip and fall incidents more than doubled between 1992 and 2012 in the United States (Injury Facts 2015 Edition-NSC). Five Key Items In the attached CNA Slip and Fall Claim Kit, you will find Recognizing Suspect or Fraudulent Claims comprehensive materials to assist you in the event a slip or fall Slip, and fall accidents are often not witnessed and usually result in occurs on your premises, resulting in injury. Start by taking a look soft tissue or “invisible” injuries. Because of these characteristics, at a few key areas covered in our kit: such incidents are prime candidates for fraud. By recognizing slip and fall fraud indicators and reporting them to CNA, you can help Timely Notice of Loss to fight this crime and protect yourself from false claims. Prompt reporting of slip or fall claims to CNA can make a Learn More. difference. If CNA is notified in a timely manner, we can act immediately in determining liability and assessing damages, thus Sidewalk Law and Risk Transfer possibly avoiding litigation, which results in overall lower claim Whether you are strolling down Main Street or running across costs. -

1 United States District Court Northern District Of

Case: 1:14-cv-05501 Document #: 34 Filed: 03/10/15 Page 1 of 14 PageID #:<pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION DOROTHY PAPACHRISTOS, ) ) No. 14 CV 5501 Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Magistrate Judge Young B. Kim ) HILTON MANAGEMENT, LLC, ) ) March 10, 2015 Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION and ORDER In this diversity suit Dorothy Papachristos alleges that in April 2012 she fell and injured herself while attending a conference at the Hilton hotel located at 720 South Michigan Avenue in Chicago, Illinois (“Michigan Avenue Hilton”). Her original and first amended complaints assert a claim against Hilton Management, LLC (“Hilton”) for negligence. Before the court is Papachristos’s motion to further amend her complaint pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 15(a) to add a claim against another defendant, Kristina Tiritilli, to this action. For the following reasons, the motion is granted, and because the new claim destroys the court’s diversity jurisdiction underlying her original complaint, this action is remanded to state court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1447(e): Background Papachristos filed her original complaint in the Circuit Court of Cook County on March 7, 2014, (R. 3-1, Notice of Removal, Ex. A), followed by an amended 1 Case: 1:14-cv-05501 Document #: 34 Filed: 03/10/15 Page 2 of 14 PageID #:<pageID> complaint on July 3, 2014, (R. 3-4, Notice of Removal, Ex. D). Papachristos alleges in her amended complaint that on April 15, 2012, she was attending a conference at the Michigan Avenue Hilton when she slipped and fell on a carpeted floor “saturated and/or wet with liquid substances.” (Id., Ex. -

Intentional Torts

Torts INTENTIONAL TORTS Intent ‐act intending to produce the harm OR ‐know that harm is substantially certain to result Battery ‐requires dual intent: 1) Act intending to cause harm or offensive contact with person (what is offensive?) 2) harmful contact directly or indirectly results *Vosburg rule used to be only need to intend contact *doesn’t have to know the full extent of the possible harm, just know that it is likely to cause harm *can be liable for any damages, unforeseen or not *thin shin rule *Transferred intent ‐ need not be person who def intended to harm ‐criminal negligence vs. tort negligence ‐small unjustifiable risk vs. big risk, gross deviation from std of care Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress 1) Intent to harm (can be imputed from facts) Wilkinson v. Downton (93) o Practical joke where guy tells woman her husband badly injured. o Rule: Such a statement, made suddenly and with apparent seriousness, could fail to produce grave effects under the circumstance upon any but an exceptionally indifferent person, and therefore an intent to produce such an effect must be imputed. 2) Outrageous Conduct RESTATEMENT 2 ‐ 46 ‐ outrageous conduct causing severe emotional distress ‐extreme or outrageous conduct ‐ who is deciding? JURY ‐intentionally or recklessly causes severe emotional distress ‐liable for emotional distress and/or bodily harm ‐liable to family members who are present regardless of bodily harm ‐liable to third parties present (not family) IF distress results in bodily harm ‐really does have to be OUTRAGEOUS‐ beyond all decency (Jury decides) ‐expansion from battery to IIED shows expansion of tort law ‐serious threats to physical well‐being are outrageous -The extreme and outrageous character might arise from knowledge that the other is peculiarly susceptible to ED by reason of a physical or mental condition or peculiarity (Amish guy).