Developmental Patterns in Stem Primary Xylem Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

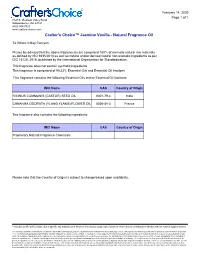

Crafter's Choice™ Jasmine Vanilla

February 14, 2020 Page 1 of 1 7820 E. Pleasant Valley Road Independence, OH 44131 (800) 908-7028 www.crafters-choice.com Crafter’s Choice™ Jasmine Vanilla - Natural Fragrance Oil To Whom it May Concern, Please be advised that the above fragrance(s) are comprised 100% of aromatic natural raw materials as defined by ISO 9235:2013 as well as natural and/or derived natural non-aromatic ingredients as per ISO 16128: 2016, published by the International Organization for Standardization. This fragrance does not contain synthetic ingredients. This fragrance is comprised of 90.33% Essential Oils and Essential Oil fractions This fragrance contains the following Essential Oils and/or Essential Oil fractions: INCI Name CAS Country of Origin RICINUS COMMUNIS (CASTOR) SEED OIL 8001-79-4 India CANANGA ODORATA (YLANG YLANG) FLOWER OIL 8006-81-3 France This fragrance also contains the following ingredients: INCI Name CAS Country of Origin Proprietary Natural Fragrance Chemicals Please note that the Country of Origin is subject to change based upon availability. * indicates unofficial INCI name, due to specific raw material used. However, the most accurate name has been chosen based on industry knowledge and raw material supplier names. The information and data contained in this document are presented for informational purposes only and have been obtained from various third party sources. Although we have made a good faith effort to present accurate information as provided to us, our ability to independently verify information and data obtained from outside sources is limited. To the best of our knowledge, the information presented herein is accurate as of the date of publication, however, it is presented without any other representation or warranty as to its completeness or accuracy and we assume no responsibility for its completeness or accuracy. -

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Lauraceae – Laurel Family

LAURACEAE – LAUREL FAMILY Plant: shrubs, trees and some vines Stem: sometimes with aromatic bark Root: Leaves: mostly evergreen, some deciduous; simple with no teeth, often elliptical and somewhat leathery; mostly alternate, less often opposite or whorled; pinnately veined with curved side veins; no stipules; sometimes glandular and aromatic Flowers: perfect but occasionally imperfect (dioecious), regular (actinomorphic); mostly in small clusters along twigs, often yellowish; tepals with 4-6 members in 2 cycles; 3-12-many, but often 9 stamens; ovary superior or inferior,1 carpel, 1 pistil Fruit: berry or drupe, single large seed Other: mostly tropical; locally, sassafras and spicebush common; Dicotyledons Group Genera: 55+ genera; locally Lindera (spice-bush), Persea, Sassafras (sassafras) WARNING – family descriptions are only a layman’s guide and should not be used as definitive LAURACEAE – LAUREL FAMILY [Northern] Spicebush; Lindera benzoin (L.) Blume Sassafras; Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees [Northern] Spicebush USDA Lindera benzoin (L.) Blume Lauraceae (Laurel Family) Oak Openings Metropark, Lucas County, Ohio Notes: shrub; flowers yellow (prior to leaves), in clusters (dioecious); leaves ovate, entire, shiny green above, somewhat whitened below; bark ‘warty’ (pores); winter buds green, stalked, in alternate clusters; twigs hairy or not, often greenish; fruit a red berry or drupe; aromatic; spring [V Max Brown, 2005] Sassafras USDA Sassafras albidum (Nutt.) Nees Lauraceae (Laurel Family) Oak Openings Metropark, Lucas County, Ohio Notes: shrub or tree; flowers small and yellow; leaves alternate, lobed or not (variable), aromatic; bark deeply grooved and ridged; twigs often green (hairy or not – varieties); fruit a blue to purple drupe on red pedicel; spring [V Max Brown, 2005]. -

Morphological Nature of Floral Cup in Lauraceae

l~Yoc. Indian Acad. Sci., Vol. 88 B, Part iI, Number 4, July 1979, pp. 277-281, @ printed in India. Morphological nature of floral cup in Lauraceae S PAL School of Plant Morphology, Meerut College, Meerut 250 001 MS received 19 June 1978 Abstract. On the basis of anatomical criteria the floral cup of Lauraceae can be regarded as appendicular, as the traces entering into the floral cup are morphologi- cally compound, differentiated into tepal and stamen traces at higher levels. The ontogenetic studies also support this contention. The term Perigynous hypanthium is retained for the floral cup of Lauraceae as it is formed as a result of intercalary growth occurring underneath the region of perianth and androecium. Keywords. Lauraceae; floral cup; morphological nature; appendicular; peri- gynous hypanthium. 1. Introduction The family Lauraceae has received comparatively little attention from earlier workers because of difficulty in procuring the material. So far very little work has been done on the floral anatomy of this family (Reece 1939 ; Sastri 1952 ; Pal 1974). There has been considerable difference of opinion regarding the nature of floral cup in angiosperms. The present work was initiated to study the morphological nature of the floral cup. 2. Materials and methods The present investigation embodies the results of observations on 21 species of the Lauraceae. The material of Machilus duthiei King ex Hook.f., M. odoratissima Nees, Persea gratissima Gaertn.f., Phoebe cooperiana Kanjilal and Das, P. goal- parensis Hutch., P. hainesiana Brandis, Alseodaphne keenanii Gamble, A. owdeni Parker, Cinnamomum camphora Nees and Eberm, C. cecidodaphne Meissn., C. tamala Nees and Eberm, C. -

Primitive Angiosperm Flower – a Discussion*

Acta Bot. Neerl. 23(4), August 1974, p. 461-471. The structure and function of the primitive Angiosperm flower – a discussion* Gerhard Gottsberger Departamentode Botanica, Faculdade de Ciencias Medicas e Biologicas de Botucatu, Estado de Sao Paulo, Brazil SUMMARY Morphological and functional features of primitive entomophilous Angiosperm flowers are discussed and confronted with modem conceptions onearly Angiosperm differentiation. Evidence is put forward to show that large, solitary and terminally-borne flowers are not most primitive in the Angiosperms, but rather middle-sized ones, groupedinto lateral flower aggregates or inflorescences. It is believed that most primitive, still unspecialized Angiosperm flowers were pollinated casuallyby beetles. Only in a later phase did they graduallybecome adaptedto the more effective but more devastating type of beetle pollination. Together with this specialization, flower enlargment, reduction of inflorescences, numerical increase of stamens and carpels, and their more dense aggregationand flatteningmight have occurred. In have maintained the archaic condi- regard to pollination,many primitive Angiosperms tion of because beetles still dominant insect whereas in cantharophily, are a group, dispersal they have been largely forced to switch over from the archaic saurochory to the more modern modes of dispersal by birds and mammals,since duringthe later Mesozoic the dominance of reptiles had come to an end. The prevailing ideas regarding the primitiveness of Angiosperm flower struc- be somewhat Is the -

Microsoft Photo Editor

Environmental research on the impact of bumblebees in Australia and facilitation of national communication for and against further introductions Kaye Hergstrom Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery Project Number: VG99033 VG99033 This report is published by Horticulture Australia Ltd to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for the vegetable industry. The research contained in this report was funded by Horticulture Australia Ltd with the financial support of the vegetable industry and Hydroponic Farmers Federation. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of Horticulture Australia Ltd or any authority of the Australian Government. The Company and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this report and readers should rely upon their own enquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. ISBN 0 7341 0532 0 Published and distributed by: Horticulture Australia Ltd Level 1 50 Carrington Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 E-Mail: [email protected] © Copyright 2002 Environmental Research on the Impact of Bumblebees in Australia and Facilitation of National Communication for/against Further Introduction Prepared by Kaye Hergstrom1, Roger Buttermore1, Owen Seeman2 and Bruce McCorkell2 1Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 40 Macquarie St, Hobart Tas., 2Department of Primary Industries, Water and the Environment, Tas. 13 St Johns Ave, New Town, Tas. Horticulture Australia Project No: VG99033 The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support provided by: Horticulture Australia Additional support in kind has been provided by: The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Front cover illustration by Mike Tobias; design by Lexi Clark Any recommendations contained in this publication do not necessarily represent current HRDC policy. -

Research Matters Newsletter of the Australian Flora Foundation

A charity fostering scientific research into the biology and cultivation of the Australian flora Research Matters Newsletter of the Australian Flora Foundation No. 31, January 2020 Inside 2. President’s Report 2019 3. AFF Grants Awarded 5. Young Scientist Awards 8. From Red Boxes to the World: The Digitisation Project of the National Herbarium of New South Wales – Shelley James and Andre Badiou 13. Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae) aka Guinea Flowers – Betsy Jackes 18. The Joy of Plants – Rosanne Quinnell 23. What Research Were We Funding 30 Years Ago? 27. Financial Report 28. About the Australian Flora Foundation President’s Report 2019 Delivered by Assoc. Prof. Charles Morris at the AGM, November 2019 A continuing development this year has been donations from Industry Partners who wish to support the work of the Foundation. Bell Art Australia started this trend with a donation in 2018, which they have continued in 2019. Source Separation is now the second Industry Partner sponsoring the Foundation, with a generous donation of $5,000. Other generous donors have been the Australian Plants Society (APS): APS Newcastle ($3,000), APS NSW ($3,000), APS Sutherland ($500) and SGAP Mackay ($467). And, of course, there are the amounts from our private donors. In August, the Council was saddened to hear of the death of Dr Malcolm Reed, President of the Foundation from 1991 to 1998. The Foundation owes a debt of gratitude to Malcolm; the current healthy financial position of the Foundation has its roots in a series of large donations and bequests that came to the Foundation during his tenure. -

The Laurel Or Bay Forests of the Canary Islands

California Avocado Society 1989 Yearbook 73:145-147 The Laurel or Bay Forests of the Canary Islands C.A. Schroeder Department of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles The Canary Islands, located about 800 miles southwest of the Strait of Gibraltar, are operated under the government of Spain. There are five islands which extend from 15 °W to 18 °W longitude and between 29° and 28° North latitude. The climate is Mediterranean. The two eastern islands, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, are affected by the Sahara Desert of the mainland; hence they are relatively barren and very arid. The northeast trade winds bring moisture from the sea to the western islands of Hierro, Gomera, La Palma, Tenerife, and Gran Canaria. The southern ends of these islands are in rain shadows, hence are dry, while the northern parts support a more luxuriant vegetation. The Canary Islands were prominent in the explorations of Christopher Columbus, who stopped at Gomera to outfit and supply his fleet prior to sailing "off the map" to the New World in 1492. Return voyages by Columbus and other early explorers were via the Canary Islands, hence many plants from the New World were first established at these points in the Old World. It is suspected that possibly some of the oldest potato germplasm still exists in these islands. Man exploited the islands by growing sugar cane, and later Mesembryanthemum crystallinum for the extraction of soda, cochineal cactus, tomatoes, potatoes, and finally bananas. The banana industry is slowly giving way to floral crops such as strelitzia, carnations, chrysanthemums, and several new exotic fruits such as avocado, mango, papaya, and carambola. -

Computer Vision Cracks the Leaf Code

Computer vision cracks the leaf code Peter Wilfa,1, Shengping Zhangb,c,1, Sharat Chikkerurd, Stefan A. Littlea,e, Scott L. Wingf, and Thomas Serreb,1 aDepartment of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; bDepartment of Cognitive, Linguistic and Psychological Sciences, Brown Institute for Brain Science, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912; cSchool of Computer Science and Technology, Harbin Institute of Technology, Weihai 264209, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; dAzure Machine Learning, Microsoft, Cambridge, MA 02142; eLaboratoire Ecologie, Systématique et Evolution, Université Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France; and fDepartment of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013 Edited by Andrew H. Knoll, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved February 1, 2016 (received for review December 14, 2015) Understanding the extremely variable, complex shape and venation species (15–19), and there is community interest in approaching this characters of angiosperm leaves is one of the most challenging problem through crowd-sourcing of images and machine-identifi- problems in botany. Machine learning offers opportunities to analyze cation contests (see www.imageclef.org). Nevertheless, very few large numbers of specimens, to discover novel leaf features of studies have made use of leaf venation (20, 21), and none has angiosperm clades that may have phylogenetic significance, and to attempted automated learning and classification above the species use those characters to classify unknowns. Previous computer vision level that may reveal characters with evolutionary significance. approaches have primarily focused on leaf identification at the species There is a developing literature on extraction and quantitative level. It remains an open question whether learning and classification analyses of whole-leaf venation networks (22–25). -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities of Cananga Odorata (Ylang-Ylang)

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2015, Article ID 896314, 30 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/896314 Review Article Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities of Cananga odorata (Ylang-Ylang) Loh Teng Hern Tan,1 Learn Han Lee,1 Wai Fong Yin,2 Chim Kei Chan,3 Habsah Abdul Kadir,3 Kok Gan Chan,2 and Bey Hing Goh1 1 JeffreyCheahSchoolofMedicineandHealthSciences,MonashUniversityMalaysia,46150BandarSunway, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia 2Division of Genetic and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Science, Institute of Biological Sciences, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 3Biomolecular Research Group, Biochemistry Program, Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Correspondence should be addressed to Bey Hing Goh; [email protected] Received 30 April 2015; Revised 4 June 2015; Accepted 9 June 2015 AcademicEditor:MarkMoss Copyright © 2015 Loh Teng Hern Tan et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Ylang-ylang (Cananga odorata Hook. F. & Thomson) is one of the plants that are exploited at a large scale for its essential oil which is an important raw material for the fragrance industry. The essential oils extracted via steam distillation from the plant have been used mainly in cosmetic industry but also in food industry. Traditionally, C. odorata is used to treat malaria, stomach ailments, asthma, gout, and rheumatism. The essential oils or ylang-ylang oil is used in aromatherapy and is believed to be effective in treating depression, high blood pressure, and anxiety. -

Drupe. Fruit with a Hard Endocarp (Figs. 67 and 71-73); E.G., and Sterculiaceae (Helicteres Guazumaefolia, Sterculia)

Fig. 71. Fig. 72. Fig. 73. Drupe. Fruit with a hard endocarp (figs. 67 and 71-73); e.g., and Sterculiaceae (Helicteres guazumaefolia, Sterculia). Anacardiaceae (Spondias purpurea, S. mombin, Mangifera indi- Desmopsis bibracteata (Annonaceae) has aggregate follicles ca, Tapirira), Caryocaraceae (Caryocar costaricense), Chrysobal- with constrictions between successive seeds, similar to those anaceae (Licania), Euphorbiaceae (Hyeronima), Malpighiaceae found in loments. (Byrsonima crispa), Olacaceae (Minquartia guianensis), Sapin- daceae (Meliccocus bijugatus), and Verbenaceae (Vitex cooperi). Samaracetum. Aggregate of samaras (fig. 74); e.g., Aceraceae (Acer pseudoplatanus), Magnoliaceae (Liriodendron tulipifera Hesperidium. Septicidal berry with a thick pericarp (fig. 67). L.), Sapindaceae (Thouinidium dodecandrum), and Tiliaceae Most of the fruit is derived from glandular trichomes. It is (Goethalsia meiantha). typical of the Rutaceae (Citrus). Multiple Fruits Aggregate Fruits Multiple fruits are found along a single axis and are usually coalescent. The most common types follow: Several types of aggregate fruits exist (fig. 74): Bibacca. Double fused berry; e.g., Lonicera. Achenacetum. Cluster of achenia; e.g., the strawberry (Fra- garia vesca). Sorosis. Fruits usually coalescent on a central axis; they derive from the ovaries of several flowers; e.g., Moraceae (Artocarpus Baccacetum or etaerio. Aggregate of berries; e.g., Annonaceae altilis). (Asimina triloba, Cananga odorata, Uvaria). The berries can be aggregate and syncarpic as in Annona reticulata, A. muricata, Syconium. Syncarp with many achenia in the inner wall of a A. pittieri and other species. hollow receptacle (fig. 74); e.g., Ficus. Drupacetum. Aggregate of druplets; e.g., Bursera simaruba THE GYMNOSPERM FRUIT (Burseraceae). Fertilization stimulates the growth of young gynostrobiles Folliacetum. Aggregate of follicles; e.g., Annonaceae which in species such as Pinus are more than 1 year old.