Effects of Community's Monetary Engagement on the Quality of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books & Illustrated Books

CHILDREN’S BOOKS & ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ALEPH-BET BOOKS, INC. 85 OLD MILL RIVER RD. POUND RIDGE, NY 10576 (914) 764 - 7410 CATALOGUE 109 ALEPH - BET BOOKS - TERMS OF SALE Helen and Marc Younger 85 Old Mill River Rd. Pound Ridge, NY 10576 phone 914-764-7410 fax 914-764-1356 www.alephbet.com Email - [email protected] POSTAGE: UNITED STATES. 1st book $8.00, $2.00 for each additional book. OVERSEAS shipped by air at cost. PAYMENTS: Due with order. Libraries and those known to us will be billed. PHONE orders 9am to 10pm e.s.t. Phone Machine orders are secure. CREDIT CARDS: VISA, Mastercard, American Express. Please provide billing address. RETURNS - Returnable for any reason within 1 week of receipt for refund less shipping costs provided prior notice is received and items are shipped fastest method insured VISITS welcome by appointment. We are 1 hour north of New York City near New Canaan, CT. Our full stock of 8000 collectible and rare books is on view and available. Not all of our stock is on our web site COVER ILLUSTRATION - #377 - Beatrix Potter Original Art done for Anne Carroll Moore #328 - Velveteen Rabbit - 1st in dw #305 - Rare Cold War moveable #127 - First Mickey Mouse book #253 - Lawson Ferdinand drawing sgd by Leaf #254 - Ferdinand 1st edition signed in dw Helen & Marc Younger Pg 3 [email protected] ABC MANUSCRIPT WITH BOOK, DRAWINGS AND DUMMY RARE TUCK RAG 1. ABC.ABC MANUSCRIPT. Offered here is a fantastic group of items comprising “BLACK” ABC the various phases of the development of a book from rough dummy to published work. -

14 Apple Arcade Games to Play on Launch Day from Strategy to Action to Puzzle Games, Here’S Where You Should Head First

APPLE MOBILE GAMING 11 14 Apple Arcade games to play on launch day From strategy to action to puzzle games, here’s where you should head first By Russ Frushtick @RussFrushtick Sep 19, 2019, 9:40am EDT Simogo Games Today’s launch of Apple Arcade might be overwhelming to some players. Subscribers who drop $4.99 a month get unlimited access to a large swath of games, and scrolling through the list can feel a bit like trying to find something good to watch on Netflix. The initial launch line-up includes over 50 games, but we’ve gone ahead and narrowed them down to 14 titles you’d do well to check out first. WHAT THE GOLF? Triband/The Label While there are plenty of thoughtful, story-driven games in the Apple Arcade collection, What the Golf? goes another way. What starts as a simple miniature golf game quickly evolves into a bizarre blend of physics-based chaos. One level might have you sliding an office chair around the course while another has you knocking full-sized buildings into the pin. The pick-up-and-play nature makes it an easy recommendation for your first dive into Apple Arcade. ASSEMBLE WITH CARE It makes sense that Apple would work with usTwo on an Apple Arcade release title. After all, the developer is known as one of the most successful mobile game makers ever, thanks to Monument Valley and its sequel. usTwo’s latest title, Assemble with Care, taps into humans’ love of taking things apart and putting them back together. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

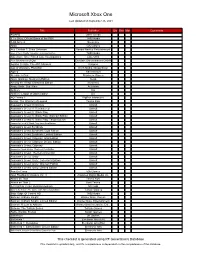

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Dual-Forward-Focus

Scroll Back The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers Itay Keren Untame [email protected] @itayke Scrolling Big World, Small Screen Scrolling: Neural Background Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Fovea centralis High cone density Sharp, hi-res central vision Parafovea Lower cone density Perifovea Lowest density, Compressed patterns. Optimized for quick pattern changes: shape, acceleration, direction Thalamus Relay sensory signals to the cerebral cortex (e.g. vision, motor) Amygdala Emotional reactions of fear and anxiety, memory regulation and conditioning "fight-or-flight" regulation Familiar visual patterns as well as pattern changes may cause anxiety unless regulated Vestibular System Balance, Spatial Orientation Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex Natural image stabilizer Conflicting sensory signals (Visual vs. Vestibular) may lead to discomfort and nausea* * much worse in 3D (especially VR), but still effective in 2D Scrolling with Attention, Interaction and Comfort Attention: Use the camera to provide sufficient game info and feedback Interaction: Make background changes predictable, tightly bound to controls Comfort: Ease and contextualize background changes Attention The Elements of Scrolling Interaction Comfort Scrolling Nostalgia Rally-X © 1980 Namco Scramble © 1981 Jump Bug © 1981 Defender © 1981 Konami Hoei/Coreland (Alpha Denshi) Williams Electronics Vanguard -

Catalis Se Annual Report 2017

CATALIS SE ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CATALIS SE CONTENTS Delivering quality to the global entertainment and media marketplace. Page Board Report 2 Financial Statements 15 Other Information 62 1 CATALIS SE BOARD REPORT The Catalis Group is comprised of Catalis SE (the ‘Company’) as the ultimate parent company of two divisions: Testronic Laboratories (Testing Division) and Curve Digital Entertainment (Publishing Division). The Testing Division provides quality assurance services to the computer games and entertainment markets and operates from offices in the US, UK, and Poland. The Publishing Division is based in the UK and comprises a publisher of independent console and PC games (Curve Digital), a development studio for third party games (Kuju Limited), and a mobile game (Crack Attack). Overview During 2017 the Catalis Group has built upon the strong foundations laid down in the prior year to consolidate our position in the games testing market and delevop our publishing business, although the Film, TV & DVD business continues to face difficult market conditions. The Group has continued to reduce external debt levels and this now provides us with a strong platform for growth. The formation of the Publishing Division in 2016 provided the cornerstone for our objective of creating a major UK video games publisher and this Division has seen significant growth in revenues and profits during 2017. The Board expects this to continue as Curve Digital establishes itself in the marketplace. Within the Testing Division, growth in the Games testing segment was offset by some shrinkage in the Film and TV sector in 2017 due to lower DVD sales in the global market. -

Ethics at Play in Undertale: Rhetoric, Identity and Deconstruction

Ethics at Play in Undertale: Rhetoric, Identity and Deconstruction Frederic SERAPHINE The University of Tokyo – ITASIA Program Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, JAPAN +81-3-5841-8769 Seraphine[at]g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the effect of ethical – and unethical – actions of the player on their perception of the self towards game characters within Toby Fox’s (2015) independent Role Playing Game (RPG) Undertale, a game often perceived as a pacifist text. With a focus on the notions of guilt and responsibility in mind, a survey with 560 participants from the Undertale fandom was conducted, and thousands of YouTube comments were scraped to better understand how the audience who watched or played the different routes of the game, refer to its characters. Through the joint analysis of the game’s semiotics, survey data, and data scraping, this paper argues that, beyond the rhetorical nature of its story, Undertale is operating a deconstruction of the RPG genre and is harnessing the emotional power of gameplay to evoke thoughts about responsibility and raise the player’s awareness about violence and its consequences. Keywords rhetoric, ethics, deconstruction, pacifism, violence, character, avatar, meta-storytelling INTRODUCTION There are some artistic experiences that stick with us for a very long time, aesthetic memories, that one may put between their first kiss and their first fight. For many of its players, a game like Undertale seems to fall into this category. Because its story puts the player in the situation of making choices that affect dramatically the course of the narrative, and the survival of its characters, it seems people who played this game grow an attachment to its fictional characters comparable to the attachment to a friend in their real life. -

Opera Acquires Yoyo Games, Launches Opera Gaming

Opera Acquires YoYo Games, Launches Opera Gaming January 20, 2021 - [Tuck-In] Acquisition forms the basis for Opera Gaming, a new division focused on expanding Opera's capabilities and monetization opportunities in the gaming space - Deal unites Opera GX, world's first gaming browser and popular game development engine, GameMaker - Opera GX hit 7 million MAUs in December 2020, up nearly 350% year-over-year DUNDEE, Scotland and OSLO, Norway, Jan. 20, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Opera (NASDAQ: OPRA), the browser developer and consumer internet brand, today announced its acquisition of YoYo Games, creator of the world's leading 2D game engine, GameMaker Studio 2, for approximately $10 million. The tuck-in acquisition represents the second building block in the foundation of Opera Gaming, a new division within Opera with global ambitions and follows the creation and rapid growth of Opera's innovative Opera GX browser, the world's first browser built specifically for gamers. Krystian Kolondra, EVP Browsers at Opera, said: "With Opera GX, Opera had adapted its proven, innovative browser tech platform to dramatically expand its footprint in gaming. We're at the brink of a shift, when more and more people start not only playing, but also creating and publishing games. GameMaker Studio2 is best-in-class game development software, and lowers the barrier to entry for anyone to start making their games and offer them across a wide range of web-supported platforms, from PCs, to, mobile iOS/Android devices, to consoles." Annette De Freitas, Head of Business Development & Strategic Partnerships, Opera Gaming, added: "Gaming is a growth area for Opera and the acquisition of YoYo Games reflects significant, sustained momentum across both of our businesses over the past year. -

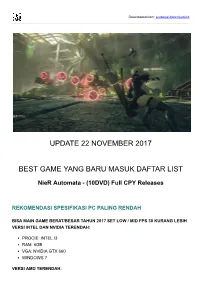

Update 22 November 2017 Best Game Yang Baru Masuk

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/premiumlink UPDATE 22 NOVEMBER 2017 BEST GAME YANG BARU MASUK DAFTAR LIST NieR Automata - (10DVD) Full CPY Releases REKOMENDASI SPESIFIKASI PC PALING RENDAH BISA MAIN GAME BERAT/BESAR TAHUN 2017 SET LOW / MID FPS 30 KURANG LEBIH VERSI INTEL DAN NVIDIA TERENDAH: PROCIE: INTEL I3 RAM: 6GB VGA: NVIDIA GTX 660 WINDOWS 7 VERSI AMD TERENDAH: PROCIE: AMD A6-7400K RAM: 6GB VGA: AMD R7 360 WINDOWS 7 REKOMENDASI SPESIFIKASI PC PALING STABIL FPS 40-+ SET HIGH / ULTRA: PROCIE INTEL I7 6700 / AMD RYZEN 7 1700 RAM 16GB DUAL CHANNEL / QUAD CHANNEL DDR3 / UP VGA NVIDIA GTX 1060 6GB / AMD RX 570 HARDDISK SEAGATE / WD, SATA 6GB/S 5400RPM / UP SSD OPERATING SYSTEM SANDISK / SAMSUNG MOTHERBOARD MSI / ASUS / GIGABYTE / ASROCK PSU 500W CORSAIR / ENERMAX WINDOWS 10 CEK SPESIFIKASI PC UNTUK GAME YANG ANDA INGIN MAINKAN http://www.game-debate.com/ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- LANGKAH COPY & INSTAL PALING LANCAR KLIK DI SINI Order game lain kirim email ke [email protected] dan akan kami berikan link menuju halaman pembelian game tersebut di Tokopedia / Kaskus ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- Download List Untuk di simpan Offline LINK DOWNLOAD TIDAK BISA DI BUKA ATAU ERROR, COBA LINK DOWNLOAD LAIN SEMUA SITUS DI BAWAH INI SUDAH DI VERIFIKASI DAN SUDAH SAYA COBA DOWNLOAD SENDIRI, ADALAH TEMPAT DOWNLOAD PALING MUDAH OPENLOAD.CO CLICKNUPLOAD.ORG FILECLOUD.IO SENDIT.CLOUD SENDSPACE.COM UPLOD.CC UPPIT.COM ZIPPYSHARE.COM DOWNACE.COM FILEBEBO.COM SOLIDFILES.COM TUSFILES.NET ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- List Online: TEKAN CTR L+F UNTUK MENCARI JUDUL GAME EVOLUSI GRAFIK GAME DAN GAMEPLAY MENINGKAT MULAI TAHUN 2013 UNTUK MENCARI GAME TAHUN 2013 KE ATAS TEKAN CTRL+F KETIK 12 NOVEMBER 2013 1. -

Animal Crossing

Alice in Wonderland Harry Potter & the Deathly Hallows Adventures of Tintin Part 2 Destroy All Humans: Big Willy Alien Syndrome Harry Potter & the Order of the Unleashed Alvin & the Chipmunks Phoenix Dirt 2 Amazing Spider-Man Harvest Moon: Tree of Tranquility Disney Epic Mickey AMF Bowling Pinbusters Hasbro Family Game Night Disney’s Planes And Then There Were None Hasbro Family Game Night 2 Dodgeball: Pirates vs. Ninjas Angry Birds Star Wars Hasbro Family Game Night 3 Dog Island Animal Crossing: City Folk Heatseeker Donkey Kong Country Returns Ant Bully High School Musical Donkey Kong: Jungle beat Avatar :The Last Airbender Incredible Hulk Dragon Ball Z Budokai Tenkaichi 2 Avatar :The Last Airbender: The Indiana Jones and the Staff of Kings Dragon Quest Swords burning earth Iron Man Dreamworks Super Star Kartz Backyard Baseball 2009 Jenga Driver : San Francisco Backyard Football Jeopardy Elebits Bakugan Battle Brawlers: Defenders of Just Dance Emergency Mayhem the Core Just Dance Summer Party Endless Ocean Barnyard Just Dance 2 Endless Ocean Blue World Battalion Wars 2 Just Dance 3 Epic Mickey 2:Power of Two Battleship Just Dance 4 Excitebots: Trick Racing Beatles Rockband Just Dance 2014 Family Feud 2010 Edition Ben 10 Omniverse Just Dance 2015 Family Game Night 4 Big Brain Academy Just Dance 2017 Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer Bigs King of Fighters collection: Orochi FIFA Soccer 09 All-Play Bionicle Heroes Saga FIFA Soccer 12 Black Eyed Peas Experience Kirby’s Epic Yarn FIFA Soccer 13 Blazing Angels Kirby’s Return to Dream -

Carolina Rodrigues Helfstein Lima 2019

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PAMPA CAROLINA RODRIGUES HELFSTEIN LIMA LEVEL UP: MULHERES EM COMBATE – UMA ANÁLISE SOBRE A PARTICIPAÇÃO FEMININA NA INDÚSTRIA DOS GAMES São Borja 2019 3 CAROLINA RODRIGUES HELFSTEIN LIMA LEVEL UP: MULHERES EM COMBATE – UMA ANÁLISE SOBRE A PARTICIPAÇÃO FEMININA NA INDÚSTRIA DOS GAMES Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado ao Curso de Jornalismo da Universidade Federal do Pampa, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Título de Bacharel em Jornalismo. Orientadora: Profª Dr. Roberta Roos Thier São Borja 2019 Ficha catalográfica elaborada automaticamente com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) através do Módulo de Biblioteca do Sistema GURI (Gestão Unificada de Recursos Institucionais) . L732l Lima, Carolina Rodrigues Helfstein Level Up: Mulheres em Combate - uma análise sobre a participação feminina na indústria dos games / Carolina Rodrigues Helfstein Lima. 161 p. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso(Graduação)-- Universidade Federal do Pampa, JORNALISMO, 2019. "Orientação: Roberta Roos Thier". 1. Participação feminina . 2. Mercado de videogames. 3. Igualdade de gênero. I. Título. 5 AGRADECIMENTOS Que aventura a graduação foi. Pensar que não sou a mesma menina que entrou na faculdade, receosa, com medo de tudo dar errado, pensando a todo momento em ligar para os pais e pedir para voltar para casa, é no mínimo, intrigante. Enquanto escrevo esta pequena parte desta grande pesquisa, me lembro de, nos primeiros dias de faculdade, ter escrito alguns versos sobre medo e angústias. Neles, a personagem principal havia saído do planeta Terra e viajado através de anos luz, com a nave mãe, até Marte – um lugar estranho povoado por alienígenas verdes, que falavam uma língua diferente. -

Cole, Tom. 2021. ”Moments to Talk About”: Designing for the Eudaimonic Gameplay Experience

Cole, Tom. 2021. ”Moments to Talk About”: Designing for the Eudaimonic Gameplay Experience. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/29689/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] “Moments to Talk About”: Designing for the Eudaimonic Gameplay Experience Thomas Cole Department of Computing Goldsmiths, University of London April 2020 (corrections December 2020) Thesis submitted in requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract This thesis investigates the mixed-affect emotional experience of playing videogames. Its contribution is by way of a set of grounded theories that help us understand the game players’ mixed-affect emotional experience, and that support ana- lysts and designers in seeking to broaden and deepen emotional engagement in videogames. This was the product of three studies: First — An analysis of magazine reviews for a selection of videogames sug- gested there were two kinds of challenge being presented. Functional challenge — the commonly accepted notion of challenge, where dexterity and skill with the controls or strategy is used to overcome challenges, and emotional chal- lenge — where resolution of tension within the narrative, emotional exploration of ambiguities within the diegesis, or identification with characters is overcome with cognitive and affective effort.