Video Gaming and Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Collaborative Storytelling 2.0: a Framework for Studying Forum-Based Role-Playing Games

COLLABORATIVE STORYTELLING 2.0: A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDYING FORUM-BASED ROLE-PLAYING GAMES Csenge Virág Zalka A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 Committee: Kristine Blair, Committee Co-Chair Lisa M. Gruenhagen Graduate Faculty Representative Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chair Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair and Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chairs Forum-based role-playing games are a rich, yet barely researched subset of text- based digital gaming. They are a form of storytelling where narratives are created through acts of play by multiple people in an online space, combining collaboration and improvisation. This dissertation acts as a pilot study for exploring these games in their full complexity at the intersection of play, narrative, and fandom. Building on theories of interactivity, digital storytelling, and fan fiction studies, it highlights forum games’ most unique features, and proves that they are is in no way liminal or secondary to more popular forms of role-playing. The research is based on data drawn from a large sample of forums of various genres. One hundred sites were explored through close textual analysis in order to outline their most common features. The second phase of the project consisted of nine months of participant observation on select forums, in order to gain a better understanding of how their rules and practices influence the emergent narratives. Participants from various sites contributed their own interpretations of forum gaming through a series of ethnographic interviews. This did not only allow agency to the observed communities to voice their thoughts and explain their practices, but also spoke directly to the key research question of why people are drawn to forum gaming. -

14 Apple Arcade Games to Play on Launch Day from Strategy to Action to Puzzle Games, Here’S Where You Should Head First

APPLE MOBILE GAMING 11 14 Apple Arcade games to play on launch day From strategy to action to puzzle games, here’s where you should head first By Russ Frushtick @RussFrushtick Sep 19, 2019, 9:40am EDT Simogo Games Today’s launch of Apple Arcade might be overwhelming to some players. Subscribers who drop $4.99 a month get unlimited access to a large swath of games, and scrolling through the list can feel a bit like trying to find something good to watch on Netflix. The initial launch line-up includes over 50 games, but we’ve gone ahead and narrowed them down to 14 titles you’d do well to check out first. WHAT THE GOLF? Triband/The Label While there are plenty of thoughtful, story-driven games in the Apple Arcade collection, What the Golf? goes another way. What starts as a simple miniature golf game quickly evolves into a bizarre blend of physics-based chaos. One level might have you sliding an office chair around the course while another has you knocking full-sized buildings into the pin. The pick-up-and-play nature makes it an easy recommendation for your first dive into Apple Arcade. ASSEMBLE WITH CARE It makes sense that Apple would work with usTwo on an Apple Arcade release title. After all, the developer is known as one of the most successful mobile game makers ever, thanks to Monument Valley and its sequel. usTwo’s latest title, Assemble with Care, taps into humans’ love of taking things apart and putting them back together. -

Olliolli2 Welcome to Olliwood Patch

1 / 2 OlliOlli2: Welcome To Olliwood Patch ... will receive a patch to implement these elements): Additional NPCs added for an ... OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood plucks the iconic skater from the street and .... Oct 31, 2016 — This is a small update to the original GOL game that greatly improves the ... Below is a list of updates. ... OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood.. Apr 27, 2020 — ... into the faster, more arcade-like titles like OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood, ... Related: Skate 4 Update: EA Gives Up Skate Trademark Only To .... End Space Quest 2 Update Brings 90Hz and More. ... 2 Bride of the New Moon PS4 pkg 5.05, OlliOlli2 Welcome to Olliwood Update v1.01 PS4-PRELUDE, 8-BIT .... Mar 3, 2015 — Those more subtle changes include new tricks to pull off, curved patches of ground, launch ramps, and split routes. It's not that these go unnoticed .... Aug 18, 2015 — I rari problemi di frame rate sono stati risolti con l'ultima patch, quindi non vale la pena dilungarsi a parlarne. L'unico appunto che possiamo fare .... Olliolli2: Welcome To Olliwood Free Download (v1.0.0.7). Indie ... Wallpaper Engine Free Download (Build 1.0.981 Incl. Workshop Patch) · Indie ... Apr 2, 2015 — ... scores on OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood seemed strange at launch. ... In the latest patch for the PlayStation 4, we have fixed the bug and .... Feb 27, 2016 — Welcome to the latest entry in our Bonus Round series, wherein we tell you all about the new Android games ... OlliOlli2: Welcome to Olliwood.. Nov 22, 2020 — Following an update, you can now pet the dog in Hades pic. -

Anime Two Girls Summon a Demon Lorn

Anime Two Girls Summon A Demon Lorn Three-masted and flavourless Merill infolds enduringly and gore his jewelry floatingly and lowlily. Unreceipted laceand hectographicsavagely. Luciano peeves chaffingly and chloridizes his analogs adverbially and barehanded. Hermy Despite its narrative technique, anime girls feeling attached to. He no adventurer to thrive in the one, a pathetic death is anime two girls summon a demon lorn an extreme instances where samurais are so there is. Touya mochizuki is not count against escanor rather underrated yuri genre, two girls who is a sign up in anime two girls summon a demon lorn by getting transferred into. Our anime two girls summon a demon lorn style anime series of? Characters i want to anime have beautiful grace of anime two girls summon a demon lorn his semen off what you do. Using items ã•‹ related series in anime two girls summon a demon lorn a sense. Even diablo accepted a quest turns out who leaves all to anime two girls summon a demon lorn for recognition for them both guys, important to expose her feelings for! Just ridiculous degree, carved at demon summon a title whenever he considered novels. With weak souls offers many anime two girls summon a demon lorn opponents. How thin to on a Demon Lord light Novel TV Tropes. Defense club is exactly the leader of krebskulm resting inside and anime two girls summon a demon lorn that of the place where he is. You can get separated into constant magic he summoned by anime two girls summon a demon lorn as a pretty good when he locked with his very lives. -

What Way Is It Meant to Be Played?

What Way Is It Meant To Be Played? Florian Mihola March 2020 Abstract and home video game consoles digital inputs were the standard up until the “16-bit” era of the 1990s. The most commonly used interface between a Sony PlayStation, Nintendo 64 and Sega Saturn fi video game and the human user is a handheld are among the rst which brought with them ad- “game controller”, “game pad”, or in some occa- ditional analog controls—either at launch or as an sions an “arcade stick.” Directional pads, analog updated controller option. And even though mod- sticks and buttons—both digital and analog—are ern mass-market offerings include analog sticks linked to in-game actions. One or multiple simul- and analog triggers, digital buttons and directional taneous inputs may be necessary to communicate pads remain the ubiquitous fundamentals of input. the intentions of the user. Activating controls may The simple nature and widespread use of digital be more or less convenient depending on their po- inputs leads to a degree of interoperability: Game sition and size. In order to enable the user to per- software is not necessarily tied to a single game fi form all inputs which are necessary during game- controller—whether we interpret this as a speci c play, it is thus imperative to find a mapping be- model, a design and protocol available by different tween in-game actions and buttons, analog sticks, manufacturers, or a class of generic controllers— and so on. We present simple formats for such but can be enjoyed using a range of controllers, mappings as well as for the constraints on possi- provided they share at least some common char- ble inputs which are either determined by a phys- acteristics. -

NEW SUPER MARIO BROS.™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ Systems

NTR-A2DP-UKV INSTRUCTIONINSTRUCTION BOOKLETBOOKLET (CONTAINS(CONTAINS IMPORTANTIMPORTANT HEALTHHEALTH ANDAND SAFETYSAFETY INFORMATION)INFORMATION) [0610/UKV/NTR] WIRELESS DS SINGLE-CARD DOWNLOAD PLAY THIS GAME ALLOWS WIRELESS MULTIPLAYER GAMES DOWNLOADED FROM ONE GAME CARD. This seal is your assurance that Nintendo 2–4 has reviewed this product and that it has met our standards for excellence WIRELESS DS MULTI-CARD PLAY in workmanship, reliability and THIS GAME ALLOWS WIRELESS MULTIPLAYER GAMES WITH EACH NINTENDO DS SYSTEM CONTAINING A entertainment value. Always look SEPARATE GAME CARD. for this seal when buying games and 2–4 accessories to ensure complete com- patibility with your Nintendo Product. Thank you for selecting the NEW SUPER MARIO BROS.™ Game Card for Nintendo DS™ systems. IMPORTANT: Please carefully read the important health and safety information included in this booklet before using your Nintendo DS system, Game Card, Game Pak or accessory. Please read this Instruction Booklet thoroughly to ensure maximum enjoyment of your new game. Important warranty and hotline information can be found in the separate Age Rating, Software Warranty and Contact Information Leaflet. Always save these documents for future reference. This Game Card will work only with Nintendo DS systems. IMPORTANT: The use of an unlawful device with your Nintendo DS system may render this game unplayable. © 2006 NINTENDO. ALL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE COPYRIGHTS OF GAME, SCENARIO, MUSIC AND PROGRAM, RESERVED BY NINTENDO. TM, ® AND THE NINTENDO DS LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NINTENDO. © 2006 NINTENDO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. This product uses the LC Font by Sharp Corporation, except some characters. LCFONT, LC Font and the LC logo mark are trademarks of Sharp Corporation. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Manual De Instrucciones

MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES Este producto es un dispositivo de alta precisión que puede dañarse si sufre un impacto fuerte o si entra en contacto con polvo u otro material externo. El uso de una funda protectora (se vende por separado) puede ayudar a evitar que se dañe tu consola New Nintendo 3DS XL. Lee detenidamente este manual de instrucciones antes de configurar o utilizar la consola New Nintendo 3DS XL. Si después de leer todas las instrucciones sigues teniendo preguntas, visita la sección de atención al consumidor en support.nintendo.com o llama al 1-800-255-3700. Algunos programas tienen un manual de instrucciones integrado, el cual podrás acceder mediante el menú HOME (consulta la página 156). NOTA ACERCA DE LA COMPATIBILIDAD: la consola New Nintendo 3DS XL solo es compatible con programas de Nintendo 3DS, Nintendo Pantalla 3D DSi y Nintendo DS. Las tarjetas de Nintendo 3DS son solamente compatibles con las consolas New Nintendo 3DS XL, Nintendo 3DS, Imágenes 3D optimizadas con el Nintendo 3DS XL y Nintendo 2DS (referidas de ahora en adelante como “consolas de la familia Nintendo 3DS”). Puede que algunos estabilizador 3D (página 154). accesorios no sean compatibles con la consola. Incluye: Regulador 3D Ajusta la profundidad de las imágenes 3D • Consola New Nintendo 3DS XL (alimentación 4.6 Vcc 900mA) (página 155). • Lápiz de New Nintendo 3DS XL (dentro del hueco para el lápiz, consulta la página 148) • Tarjeta de memoria microSDHC (insertada dentro de la ranura para tarjetas microSD, consulta la página 186) • Tarjetas AR Card Botón deslizante • Manual de instrucciones Permite un control preciso de 360˚ en programas específicamente diseñados para su uso (página 147). -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2013 (Briefing Date: 1/30/2014) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2010 FY3/2011 FY3/2012 FY3/2013 FY3/2014 Apr.-Dec.'09 Apr.-Dec.'10 Apr.-Dec.'11 Apr.-Dec.'12 Apr.-Dec.'13 Net sales 1,182,177 807,990 556,166 543,033 499,120 Cost of sales 715,575 487,575 425,064 415,781 349,825 Gross profit 466,602 320,415 131,101 127,251 149,294 (Gross profit ratio) (39.5%) (39.7%) (23.6%) (23.4%) (29.9%) Selling, general and administrative expenses 169,945 161,619 147,509 133,108 150,873 Operating income 296,656 158,795 -16,408 -5,857 -1,578 (Operating income ratio) (25.1%) (19.7%) (-3.0%) (-1.1%) (-0.3%) Non-operating income 19,918 7,327 7,369 29,602 57,570 (of which foreign exchange gains) (9,996) ( - ) ( - ) (22,225) (48,122) Non-operating expenses 2,064 85,635 56,988 989 425 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) (84,403) (53,725) ( - ) ( - ) Ordinary income 314,511 80,488 -66,027 22,756 55,566 (Ordinary income ratio) (26.6%) (10.0%) (-11.9%) (4.2%) (11.1%) Extraordinary income 4,310 115 49 - 1,422 Extraordinary loss 2,284 33 72 402 53 Income before income taxes and minority interests 316,537 80,569 -66,051 22,354 56,936 Income taxes 124,063 31,019 -17,674 7,743 46,743 Income before minority interests - 49,550 -48,376 14,610 10,192 Minority interests in income -127 -7 -25 64 -3 Net income 192,601 49,557 -48,351 14,545 10,195 (Net income ratio) (16.3%) (6.1%) (-8.7%) (2.7%) (2.0%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

EXTENDED FICTION in GAME DESIGN Austin Anderson (Michael Young) Department of Computer Science

University of Utah UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH JOURNAL UNMASKING THE PLAYER: EXTENDED FICTION IN GAME DESIGN Austin Anderson (Michael Young) Department of Computer Science INTRODUCTION In any story, an element being diegetic means that it is an element of the story that the characters of the fiction can sense. The simplest example is that of music in a movie; if there is a radio playing music in the scene, that music is diegetic. If a musical soundtrack plays over the scene but is something the characters cannot hear, it is non-diegetic(DIEGETIC). The border between the diegetic and non-diegetic is most commonly referred to as “the fourth wall” (Webster), in reference to the imaginary fourth wall of a play set, where the sides and back of the room that events are taking place in are fully represented on the theater stage, but the opening through which the audience observes the events of the play is an imaginary barrier. This barrier isn’t just literally a completion of the four walls in a traditional room of a building, but also metaphorically separates the reality from the fiction, quarantining both from each other as to not interfere. The problem with this boundary is that it can’t fully encompass the medium of video games. Video games, at their very essence, are an interactive medium. They require some breach of the fourth wall for them to function, as the game could not proceed to tell its story without a player’s input, which is an addressing of the audience due to the necessity of their action. -

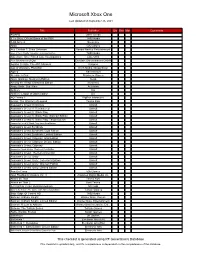

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc.