Vajrayoginī: Her Visualizations, Rituals, & Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

Full Activities Report 2010-2020

Activities Report 2010 - 2020 Celebrating our 10th Anniversary! Shang Shung Institute UK Activities Report 2010 - 2020 Dear Friends, The Shang Shung Institute UK (SSIUK) is pleased to present a summary of the acti- vities that our team of dedicated staff, volunteers and supporters have carried out since its inception in May 2010 under the guidance and direction of the late Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. Our activities since 2010 are listed below as well as our fundraising projects. This will give you an overview of our work in the past years. Our heartfelt thanks go to our founder, the late Chögyal Namkhai Norbu. We would also like to express our gratitude to Dr Nathan Hill (SOAS) for his generous and untiring commitment and to the many sup- porters, volunteers and donors who graciously share their time, skills and resouces to help the Shang Shung Institute UK (SSIUK) fulfill its mission to preserve, diffuse and promote Tibetan culture throu- ghout the world. In particular, we would like to give thanks and pay our respects to the late Dominic Kennedy and Judith Allan who both played pivotal roles in the establishment of the Institute here in the UK. The SSIUK is a nonprofit organisation that relies on your support to continue and develop. We hope that this report serves to inspire you, and we would like to invite you to actively participate in our work through donations, sponsorship and legacies. You can see details of how you may do this on the last page of this booklet. With our very best wishes, Julia Lawless - International Director of Tibetan Culture Prof. -

Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3

WISDOM ACADEMY Buddhist Philosophy in Depth, Part 3 JAY GARFIELD Lessons 6: The Transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet, and the Shentong-Rangtong Debate Reading: The Crystal Mirror of Philosophical Systems "Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism," pages 71-75 "The Nyingma Tradition," pages 77-84 "The Kagyu Tradition," pages 117-124 "The Sakya Tradition," pages 169-175 "The Geluk Tradition," pages 215-225 CrystalMirror_Cover 2 4/7/17 10:28 AM Page 1 buddhism / tibetan THE LIBRARY OF $59.95US TIBETAN CLASSICS t h e l i b r a r y o f t i b e t a n c l a s s i c s T C! N (1737–1802) was L T C is a among the most cosmopolitan and prolific Tspecial series being developed by e Insti- Tibetan Buddhist masters of the late eighteenth C M P S, by Thuken Losang the crystal tute of Tibetan Classics to make key classical century. Hailing from the “melting pot” Tibetan Chökyi Nyima (1737–1802), is arguably the widest-ranging account of religious Tibetan texts part of the global literary and intel- T mirror of region of Amdo, he was Mongol by heritage and philosophies ever written in pre-modern Tibet. Like most texts on philosophical systems, lectual heritage. Eventually comprising thirty-two educated in Geluk monasteries. roughout his this work covers the major schools of India, both non-Buddhist and Buddhist, but then philosophical large volumes, the collection will contain over two life, he traveled widely in east and inner Asia, goes on to discuss in detail the entire range of Tibetan traditions as well, with separate hundred distinct texts by more than a hundred of spending significant time in Central Tibet, chapters on the Nyingma, Kadam, Kagyü, Shijé, Sakya, Jonang, Geluk, and Bön schools. -

Lama Jampa Thaye 2016-Sm

A Concise Explanation of Lojong: the powerful method to develop wisdom and compassion. October 28-30, 2016 Bodhi Path Chicago Friday: 7pm - 9pm Saturday: 1pm - 6pm Sunday: 10:30am - 12:30pm and 2pm - 4pm Lama Jampa Thaye is a scholar and meditation master trained in the Sakya and Karma Kagyu traditions of Tibetan Buddhism and authorized as a lama by his Join Bodhi Path two masters, Karma Thinley Chicago for a year of Rinpoche and H.H. Sakya special teaching events Trizin. He holds a doctorate from the University of Manchester celebrating our for his work on Tibetan religious 10th anniversary! history and lectured in uni- versities for over twenty years. In 1974, H.H. the Sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa appointed Lama Jampa to the Karma Kagyu Trust (UK) and he is now a member of the international teaching faculty of the Karmapa International Buddhist Institute in Delhi. Lojong, or Mind Training, is a comprehensive practice, which embodies the entire path to awakening. The Buddha recog- situation, we must train our mind. In one of his last programs before his death in 2014, Shamar Rinpoche taught the text, A Concise Lojong Manual*, at Lama Jampa Thaye’s center in Manchester, England. Lama Jampa Thaye will now bring this special teaching to Chicago. Suggested Donation: $40 per day, $80 for the weekend.** Bring your own lunch on Sunday or step out for a bite. For more information visit our website: www.bodhipath.org/chicago Email: [email protected] , or call 773.234.8648 4043 N. Ravenswood Ave, SUITE 214, Chicago, IL 60613 * A Concise Lojong Manual was written by the 5th Shamar Rinpoche, Könchok Yenlak (1526–83). -

Women in Buddhism Glimpses of Space

Women in Buddhism Glimpses of Space: The Feminine Principle and EVAM. in Glimpses of the Profound. Chöygam Trungpa Rinpoche. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications, 2016) Yasodharā, The Wife of the Bōdhisattva: the Sinhala Yasodharāvata (The Story of Yasodharā) and the Sinhala Yasodharāpadānaya (The Sacred Biography of Yasodharā). trans. Ranjini Obeyesekere. (Albany NY: State University of New York Press, 2009) When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet. Hildegard Diemberger. (New York NY: Columbia University Press, 2007) The Lives and Liberation of Princess Mandarava: The Indian Consort of Padmasambhava. trans. Lama Chonam and Sangye Khandro. (Somerville MA: Wisdom Publications, 1998) Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro. Sarah H. Jacoby. (New York NY: Columbia University Press, 2014) The Elders’ Verses II: Therīgāthā. trans. K.R. Norman. (Oxford: Pali Text Society, 1995) Women of Wisdom. Tsultrim Allione. (New York NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul Inc., 1984‐ 1987) Dakini’s Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Judith Simmer‐ Brown. (Boston MA: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 2001) Machig Labdrön and the Foundations of Chöd. Jérôme Edou. (Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1996) Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists, & the Art of the Self. Anne Carolyn Klein. (Ithaca NY: Snow Lion Publications, 1995‐2008) Therigatha: Poems of the First Buddhist Women. Charles Hallisey. (Boston MA: Harvard University Press, 2015) The Lotus‐Born: the Life Story of Padmasambhava. Yeshe Tsogyal. trans. Erik Pema Kunsang. (Hong Kong: Rangjung Yeshe Publications, 1993) Sky Dancer: The Secret Life and Songs of Yeshe Tsogyel. trans. Keith Dowman. (Ithaca NY: Snow Lion, 1984‐1996) Restricted to Vajrayana Students: Niguma, Lady of Illusion. -

2011, Volume 20, Number 1

Winter 2011 Volume 20, Number 1 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Sharing Impressions, Meeting Expectations: Evaluating the 12th Sakyadhita Conference Titi Soentoro The Question of Lineage in Tibetan Buddhism: A Woman’s Perspective Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo Lipstick Buddhists and Dharma Divas: Buddhism in the Most Unlikely Packages Lisa J. Battaglia The Anti-Virus Enlightenment Hyunmi Cho Risks and Opportunities of Scholarly Engagement with Buddhism Christine Murphy SHARING IMPRESSIONS, MEETING EXPECTATIONS Evaluating the 12th Sakyadhita Conference Grace Schireson in Interview By Titi Soentoro Janice Tolman Full Ordination for Women and It was a great joy to be among such esteemed scholars, nuns, and laywomen at the 12th Sakyadhita the Fourfold Sangha International Conference on Buddhist Women held in Bangkok from June 12 to 18, 2011. It felt like such Santacitta Bhikkhuni an honor just to be in their company. This feeling was shared by all the participants. Around the general A SeeSaw theme, “Leading to Liberation, the conference addressed many issues of Buddhist women, including Wendy Lin issues that people don’t generally associate with Buddhist women, such as the environment and LGBTQ concerns. Sakyadhita in Cyberspace: Sakyadhita and the Social Media At the end of the conference, participants were asked to share their feelings and insights, and to Revolution offer suggestions for the next Sakyadhita Conference. The evaluations asked which aspects they enjoyed Charlotte B. Collins the most and the least, which panels and workshops they learned the most from, and for suggestions for themes and topics for the next Sakyadhita Conference in India. In many languages, participants shared A Tragic Episode Rebecca Paxton their reflections on all aspects of the conference Further Reading What Participants Appreciated Most Overall, respondents found the conference very interesting and enjoyable. -

2015-16 AR__ Rework__AP__Final.Cdr

2014-15 Shamar Rinpoche's unwavering commitment to preserving the lineage was his clear priority, as 2013/14 evidenced by his response to the criticism he was receiving: “I understood very well that what was good for the Karma Kagyu tradition would not be very good for me as an individual under these circumstances. Yet, I sacrificed myself for the greater good in order to protect the lineage. The reason I chose to sacrifice myself was that I had already by that time taken on the role of leadership, in accord with my position as the Shamarpa. How could I ignore something so important in order to save myself from any hardship? I took this responsibility seriously, as is my duty. I tried to be a bulldozer, in order to build up the strength of the genuine Karma Kagyu tradition.” TRIBUTE TO THE 14TH SHAMARPA MIPHAM CHOKYI LODRO Presented on the one year commemoration ceremony KARMAPA INTERNATIONAL BUDDHIST SOCIETY B 19/20 Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi -110016 INDIA +91-11-41087859 [email protected] Special Edition www.facebook.com/KIBSociety Editor: Sally J. Horne News Compiler: Khenpo Mriti Design and Layout: Sumant Chhetri, Lekshey Jorden Photography: Thule G. Jug, LeksheyJorden, Tokpa Korlo, Karmapa International Salva Magaz, Yvonne Wong and thanks to all the other Photographers Buddhist Society © Karmapa International Buddhist Society 2015 9 789383 027057 KIBS ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 DEDICATED TO SHAMAR RINPOCHE 01 Estd. 2012 KARMAPA INTERNATIONAL BUDDHIST SOCIETY Karmapa International Buddhist Society is an international organisation for charity, cultural capital and Buddhist educational opportunities. (19th January, 2012 – Registrar of Societies District South West Govt. -

Prajñatara: Bodhidharma's Master

Summer 2008 Volume 16, Number 2 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Women Acquiring the Essence Buddhist Women Ancestors: Hymn to the Perfection of Wisdom Female Founders of Tibetan Buddhist Practices Invocation to the Great Wise Women The Wonderful Benefits of a H. H. the 14th Dalai Lama and Speakers at the First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha Female Lineage Invocation WOMEN ACQUIRING THE ESSENCE An Ordinary and Sincere Amitbha Reciter: Ms. Jin-Mei Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao Chen-Lai On July 10, 1998, I invited the women of our Sangha to gather to explore the practice and lineage of women. Prajñatara: Bodhidharma’s Here are a few thoughts that helped get us started. Master Several years ago while I was visiting ZCLA [Zen Center of Los Angeles], Nyogen Sensei asked In Memory of Bhiksuni Tian Yi (1924-1980) of Taiwan me to give a talk about my experiences as a woman in practice. I had never talked about this before. During the talk, a young woman in the zendo began to cry. Every now and then I would glance her One Worldwide Nettwork: way and wonder what was happening: Had she lost a child? Ended a relationship? She cried and A Report cried. I wondered what was triggering these unstoppable tears? The following day Nyogen Sensei mentioned to me that she was still crying, and he had gently Newsline asked her if she could tell him why. “It just had not occurred to me,” she said, “that a woman could be a Buddha.” A few years later when I met her again, the emotions of that moment suddenly surfaced. -

Powa, Niguma, and Thetibetan Book of the Dead

r38 Powa,Niguma, and TheTibetanBook of theDead 'W'estern The understanding of the Tibetan doctrines The introductory verses to this famous classic state: concerning death and the afterlife, as well as of rebirth It is said rhat those ofsuperior capacity. and the Pure Lands, largely comes from the arnazing The great yogis and yoginis, popularity achieved by the Bardo Tbdol (The Tibetan Should be able to attain liberation during this uery Booh of the Dead). Originally translated by LamaKazi lifetime Dawa-Samdup and edited by Evans-Wentz, the ry27 By relying on the stagesofThntric yoga application. edition from Oxford University Pressquickly became If they do not succeedin this, then they should apply an international successand received renderings into a The methods of consciousnesstransference at the time of dozen \Testern languages.' death. Half a dozen subsequent translations of this extraordinaryTibetan work have appeared since that Euen mediocre yogis can gain liberation through this time, and the original byKazi Dawa-Samdup and transference. Evans-\Ventz remains in print. Perhaps the most acces- Howeuer, f they do not succeedin the ffirt, sible ofthese alternative renditions is that by Francesca Then they should turn to a reading of thisBardoTodol, Fremantle and Chogyam Tlungpa." a text For achieuing liberation through hearing in the bardn. In other words, the best Thntric practitioner can achieve enlightenment during his or her very lifetime. The next best should apply the yogas of transference at the time of death. The Tibetan word for this transference is powa Figure65 (consciousnesstransference), and includes both trans- Mandafa Used in The Tibetan Book ofthe Dead ference to the dharmakaya, which means the attain- Tibet;r8th century ment of enlightenment through immersion with the Pigmenton cloth clear light consciousness at the time of death and, for z8 x t8.25 in. -

The Practice of the SIX YOGAS of NAROPA the Practice of the SIX YOGAS of NAROPA

3/420 The Practice of THE SIX YOGAS OF NAROPA The Practice of THE SIX YOGAS OF NAROPA Translated, edited and introduced by Glenn H. Mullin 6/420 Table of Contents Preface 7 Technical Note 11 Translator's Introduction 13 1 The Oral Instruction of the Six Yogas by the Indian Mahasiddha Tilopa (988-1069) 23 2 Vajra Verses of the Whispered Tradition by the Indian Mahasiddha Naropa (1016-1100) 31 3 Notes on A Book of Three Inspirations by Jey Sherab Gyatso (1803-1875) 43 4 Handprints of the Profound Path of the Six Yogas of Naropa: A Source of Every Realiza- tion by Gyalwa Wensapa (1505-1566) 71 8/420 5 A Practice Manual on the Six Yogas of Naropa: Taking the Practice in Hand by Lama Jey Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) 93 6 The Golden Key: A Profound Guide to the Six Yogas of Naropa by the First Panchen Lama (1568-1662) 137 Notes 155 Glossary: Tibetan Personal and Place Names 167 Texts Quoted 171 Preface Although it is complete in its own right and stands well on its own, this collection of short commentaries on the Six Yogas of Naropa, translated from the Tibetan, was originally conceived of as a companion read- er to my Tsongkhapa's Six Yogas of Naropa (Snow Lion, 1996). That volume presents one of the greatest Tibetan treatises on the Six Yogas system, a text composed by the Tibetan master Lama Jey Tsongkhapa (1357-1419)-A Book of Three Inspirations: A Treatise on the Stages of Training in the Profound Path of Naropa's Six Yogas (Tib. -

Melody of Dharma

Melody of Dharma An Introductory Teaching on Taking Refuge Buddha Nature by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin A teaching by H.E. Ratna Vajra Rinpoche Global Ecological Crisis: An Aspirational Prayer by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin A Publication of the Office of Sakya Dolma Phodrang Dedicated to the Dharma Activities of His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 2010 • No.3 CONTENTS 3 From The Editors 5 Chogye Trichen Rinpoche / Nalendra Monastery 6 Remembering Great Masters –– Virupa 8 Virupa's Dohakosa 14 Global Ecological Crisis: An Aspirational Prayer –– by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 16 Taking Refuge –– A teaching by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin (part 2) 22 Buddha Nature –– A teaching by H.E. Ratna Vajra Rinpoche 28 News From The Phodrang: Dungsey Akasha Rinpoche 29 The Khön Family 32 Dharma Activities 32 • His Holiness' Visit to Arunachal Pradesh 34 • His Holiness’ Russian and European Teaching Tour 46 • Lamdre in Kuttolsheim 57 Mahavairocana Puja –– A brief History by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 59 Summer Retreat 59 His Holiness' Retreat House Publisher: The Office of Sakya Dolma Phodrang Editing Team: Executive Editor: Ani Jamyang Wangmo Mrs. Yang Dol Tsatultsang (Dagmo Kalden’s mother), Managing Editor: Patricia Donohue Danijela Stamatovic, Sherab Chöden , Supervising Editor: Terri Lee Rosemarie Hemscheidt Art Director/Designer: Chang Ming-Chuan Cover Photo: Nalendra Monastery, Tibet Photographs: Cristina Vanza From The Editors We are very pleased to welcome our readers to this, our third issue of Melody of Dharma, with a particularly warm greeting to our new subscribers. We wish to extend our heartfelt thanks to our sponsors, whose generosity made this issue possible, and to all those who have contributed to the magazine in one way or another. -

Texts-For-Mönlam-2020-EN.Pdf

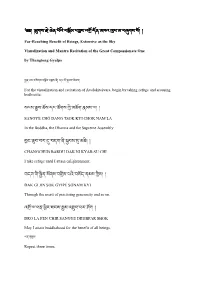

Far-Reaching Benefit of Beings, Extensive as the Sky Visualization and Mantra Recitation of the Great Compassionate One by Thangtong Gyalpo đ For the visualization and recitation of Avalokite śvara, begin by taking refuge and arousing bodhicitta: !đ"# SANGYE CHÖ DANG TSOK KYI CHOK NAM LA In the Buddha, the Dharma and the Supreme Assembly $%&đ' CHANGCHUB BARDU DAK NI KYAB SU CHI I take refuge until I attain enlightenment. đ()đ! DAK GI JIN SOK GYIPÉ SÖNAM KYI Through the merit of practising generosity and so on, đ#*+,- DRO LA PEN CHIR SANGYE DRUBPAR SHOK May I attain buddhahood for the benefit of all beings. #' Repeat three times. Then, for the deity visualization: /) DAK SOK KHAKHYAB SEMCHEN GYI For me and all sentient beings throughout the whole of space, đ01đ2 CHITSUK PEKAR DAWÉ TENG On the crowns of our heads, seated upon white lotus and moon 35#*4 HRIH LÉ PAKCHOK CHENREZIK Is a Hr īḥ, out of which noble Avalokite śvara appears— 1#678 KARSAL ÖZER NGADEN TRO Brilliantly white and radiating five-coloured rays of light. 9:;đ) DZÉ DZUM TUKJÉ CHEN GYI ZIK He has a captivating smile and gazes with eyes of compassion. +<đđ=#(9 CHAK SHYI DANGPO TALJAR DZÉ The first two of his four hands are clasped together, ?-#81@ OK NYI SHEL TRENG PEKAR NAM The lower two hold a crystal rosary and white lotus. )A DAR DANG RINCHEN GYEN GYI TRÉ He is adorned with silken garments and jewels, đBCđ2D# RIDAK PAKPÉ TÖYOK SOL And an antelope pelt is draped over his shoulder.