Plays in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosena Hill Jackson Resume

ROSENA M. HILL JACKSON 941-350-8566 [email protected] www.RosenaHill.com BROADWAY/New York Carousel Nettie Jack O’Brien/Justin Peck Prince of Broadway swing Harold Prince/ Susan Stroman After Midnight Rosena Warren Carlyle/Daryl Waters/Wynton Marsalis Carousel Ensemble Avery Fisher Hall/PBS “Live at Lincoln Center” Cotton Club Parade Rosena Encores City Center Lost in the Stars Mrs. Mckenzie Encores Z City Center Come Fly Away Featured Vocalist Marriott Marqui Theatre/Twyla Tharp The Tin Pan Alley Rag Monisha/Miss Lee Roundabout Theatre Co./Stafford arima,dir Oscar Hammerstein II: The Song is You Soloist Carnegie Hall/New York Pops Color Purple Church Lady Broadway Theatre Spamalot Lady of the Lake/Standby Mike Nichols dir. Imaginary Friends Mrs. Stillman & others Jack O'Brien dir. Oklahoma Ellen Trevor Nunn mus dir./Susan Stroman chor. Riverdance on Broadway Amanzi Soloist Gershwin Theater Marie Christine Ozelia Graciela Daniele dir. Ragtime Sarah’s Friend u/s Frank Galati, Graciela Daniele/Ford’s Center REGIONAL The Toymaker Sarah NYMF/Lawrence Edelson,dir The World Goes Round Woman #1 Pittsburgh Public Theater/Marcia Milgrom Dodge,dir Ragtime Sarah White Plains Performing Arts Center Man of Lamancha Aldonza White Plains Performning Arts Center Baby Pam/s Papermill Playhouse Dreamgirls Michelle North Carolina Theater Ain’t Misbehavin’ Armelia Playhouse on the Green Imaginary Friends Smart women soloist Globe Theater 1001 Nights Sophie George Street Playhouse Mandela (with Avery Brooks) Winnie Steven Fisher dir./Crossroads Brief History -

PETER PAN Or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up

PRESS RELEASE NORTH HIGH SCHOOL to present PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up The Appleton North High School Theatre Department will present the play PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up on May 16th through the 19th in the North High School Auditorium, 5000 North Ballard Road. This new version adapted from the original J.M. Barrie play and novel by Trevor Nunn and John Caird for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre of London enjoyed phenomenal success when first produced. The famous team known for their productions of THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF NICHOLAS NICKLEBY and the musical LES MISERABLES have painstakingly researched and restored Barrie’s original play. “. .a national masterpiece.”—London Times. This is the beloved story of Peter, Wendy, Michael, John, Capt. Hook, Smee, the lost boys, pirates, and the Indians, and of course, Tinker Bell, in their adventures in Never Land. However, for the first time, the play is here restored to Barrie’s original intentions. In the words of adaptor, John Caird: “ We were fascinated to discover that there was no one single document called PETER PAN. What we found was a tantalizing number of different versions, all of them containing some very agreeable surprises….We have made some significant alterations, the greatest of which is the introduction of a new character, the Storyteller, who is in fact the author himself.” North’s theatre director, Ron Parker, states, “This is a very different PETER PAN than the one most people are familiar with. It is neither the popular musical version nor the Disney animated recreation, but goes back to Barrie’s original play and novel. -

Simon Russell Beale Photo: Charlie Carter

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Simon Russell Beale Photo: Charlie Carter Location: London Other: Equity Height: 5'7" (170cm) Eye Colour: Grey Playing Age: 51 - 55 years Hair Colour: Greying Appearance: White Hair Length: Short Stage 2018, Stage, The Lehman Trilogy, The National Theatre, Sam Mendes 2016, Stage, Prospero, The Tempest, Royal Shakespeare Company, Gregory Doran 2015, Stage, Mr Foote, Mr Foote's Other Leg, Hampstead Theatre/Haymarket (transfer), Richard Eyre 2015, Stage, The Dean, Temple, Donmar Warehouse, Howard Davies 2014, Stage, King Lear, King Lear, National Theatre, Sam Mendes 2013, Stage, Acting Captain Terri Dennis, Privates on Parade, Noel Coward Theatre, Michael Grandage 2013, Stage, Roote, The Hothouse, Trafalgar Studios, Jamie Lloyd 2012, Stage, Timon of Athens (Critics' Circle Award 2013), Timon of Athens, National Theatre, Nicholas Hytner 2011, Stage, Jimmy, Bluebird, Atlantic Theatre Company, New York, Gaye Taylor Upchurch 2011, Stage, Stalin, Collaborators, National Theatre, Nicholas Hytner 2010, Stage, Sydney, Deathtrap, Noel Coward Theatre, Matthew Warchus 2010, Stage, Sir Harcourt Courtly, London Assurance, National Theatre, Nicholas Hytner 2009, Stage, Lopahkin, The Cherry Orchard, Brooklyn Academy/World Tour/Old Vic, Sam Mendes 2009, Stage, Leontes, The Winter's Tale, Brooklyn Academy/World Tour/Old Vic, Sam Mendes 2008, Stage, Edward, A Slight Ache, National Theatre, Iqbal Khan 2008, Stage, Landscape, National Theatre, -

Biographies (396.2

ANTONELLO MANACORDA conducteur italien • Formation o études de violon entres autres avec Herman Krebbers à Amsterdam o puis, à partir de 2002, deux ans de direction d’orchestre chez Jorma Panula. • Orchestres o 1997 : il crée, avec Claudio Abbado, le Mahler Chamber Orchestra o 2006 : nommé chef permanent de l’ensemble I Pomeriggi Musicali à Milaan o 2010 : nommé chef permanent du Kammerakademie Potsdam o 2011 : chef permanent du Gelders Orkest o Frankfurt Radio Symphony, BBC Philharmonic, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg, Sydney Symphony, Orchestra della Svizzera Italia, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Stavanger Symphony, Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Hamburger Symphoniker, Staatskapelle Weimar, Helsinki Philharmonic, Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse & Gothenburg Symphony • Fil rouge de sa carrière o collaboration artistique de longue durée avec La Fenice à Venise • Pour la Monnaie o dirigeerde in april 2016 het Symfonieorkest van de Munt in werk van Mozart en Schubert • Projets récents et futurs o Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Don Giovanni & L’Africaine à Frankfort, Lucio Silla & Foxie! La Petite Renarde rusée à la Monnaie, Le Nozze di Figaro à Munich, Midsummer Night’s Dream à Vienne et Die Zauberflöte à Amsterdam • Discographie sélective o symphonies de Schubert avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical - courroné par Die Welt) o symphonies de Mendelssohn également avec le Kammerakademie Potsdam (Sony Classical) • Pour en savoir plus o http://www.inartmanagement.com o http://www.antonello-manacorda.com CHRISTOPHE COPPENS Artiste et metteur -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Southern Comfort

FROM THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MUSICAL THEAtre’s PresideNT Welcome to our 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals! The Festival is one of the highlights of the NAMT year, bringing together 600+ industry professionals for two days of intense focus on new musical theatre works and the remarkably talented writing teams who create them. This year we are particularly excited not only about the quality, but also about the diversity—in theme, style, period, place and people—represented across the eight shows that were selected from over 150 submissions. We’re visiting 17th-century England and early 20th century New York. We’re spending some time in the world of fairy tales—but not in ways you ever have before. We’re visiting Indiana and Georgia and the world of reality TV. Regardless of setting or stage of development, every one of these shows brings something new—something thought-provoking, funny, poignant or uplifting—to the musical theatre field. This Festival is about helping these shows and writers find their futures. Beyond the Festival, NAMT is active year-round in supporting members in their efforts to develop new works. This year’s Songwriters Showcase features excerpts from just a few of the many shows under development (many with collaboration across multiple members!) to salute the amazing, extraordinarily dedicated, innovative work our members do. A final and heartfelt thank you: our sponsors and donors make this Festival, and all of NAMT’s work, possible. We tremendously appreciate your support! Many thanks, too, to the Festival Committee, NAMT staff and all of you, our audience. -

Ben Jonson and the Mirror: Folly Knows No Gender

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2001 Ben Jonson and The Mirror: Folly Knows No Gender Sherry Broadwell Niewoonder Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Niewoonder, Sherry Broadwell, "Ben Jonson and The Mirror: Folly Knows No Gender" (2001). Dissertations. 1382. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1382 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEN JONSON AND THE MIRROR: FOLLY KNOWS NO GENDER by Sherry Broadwell Niewoonder A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2001 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BEN JONSON AND THE M IR R O R : FO LLY KNOWS NO GENDER Sherry Broadwell Niewoonder, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2001 Ben Jonson, Renaissance poet and playwright, has been the subject of renewed evaluation in recent scholarship, particularly new historicism and cultural materialism. The consensus among some current scholars is that Jonson overtly practices and advocates misogyny in his dramas. Such theorists suggest that Jonson both embodies and promulgates the anti woman rhetoric of his time, basing their position on contemporary cultural material, religious tracts, and the writings of King James I. -

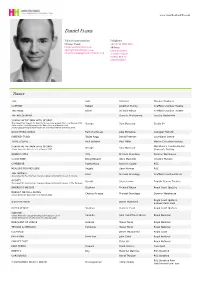

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

Contribution of Ben Jonson to Development of the English Renaissance Comedy

УДК: 821.111.09-22 Џонсон Б. ИД: 195292940 Оригинални научни рад ДОЦ. ДР СЛОБОДАН Д. ЈОВАНОВИЋ1 Факултет за правне и пословне студије „др Лазар Вркатић” Катедра за англистику, Нови Сад CONTRIBUTION OF BEN JONSON TO DEVELOPMENT OF THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE COMEDY Abstract. Ben Jonson’s Works, published in 1616, included all his comedies written that far, and meant an important precedent which helped to establish drama as lit- erary kind comparable to the rest of literature. Before that date, drama was regarded as un- worthy of the name of literature, and Jonson was the first to give it its new dignity. His comedies written after 1616 were usually published immediately after they were acted. Jonson’s theoretical interests were an expression of his intellectual aristocratism and his realistic temperament. He took pride in being able to create comedies according to the best scientific rules, and felt superior to those who made them by sheer talent. Jonson was the only theoretician among the English Renaissance dramatists, but although he was ready to fight for his rules, his application of them was broad and elastic. In his comedies there are many departures from classical models, often modified by his keen observation of every- day English life. The theory he adhered to was an abstract and rigid kind of realism, which in his practice was transformed by his gift of observation and his moral zeal into a truly realistic and satirical comic vision of life. Key words: comedy, drama, theory, classical models, everyday English life, realism, satire. 1 [email protected] 348 Зборник радова Филозофског факултета XLII (1)/2012 EXCEPTIONAL PERSONALITY, OUTSTANDING CONTRIBUTION Benjamin or Ben Jonson (1573?-1637) was the central literary personality of the first two decades of the XVII century. -

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Dialect and Voice

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Nov 16 – Feb 2017 Roseline Productions Dialect Coach for Will Ferrell, John C Reilly: Holmes and Watson Nov 2016 Sky Dialect Coach Bliss Nov 2016 BBC Dialect Coach for Zombie Boy: Silent Witness Aug 2016 Sky Dialect Coach for Iwan Rheon and Dimitri Leonidas: Riviera Jan/Feb 2016 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: ADR: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Oct 2015 Jellylegs/Sky 1 Dialect Coach: Rovers directed by Craig Cash Oct 2015 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Sept 2015 LittleRock Pictures/Sky Dialect /voice coach: Elizabeth, Michael and Marlon (Joseph Fiennes, Stockard Channing, Brian Cox) January – May 2015 BBC2/ITV, London Dialect Coach (East London): Cradle to Grave – directed by Sandy Johnson January – April 2015 Working Title/Sky Dialect Coach (Gen Am, Italian): You, Me and the Apocalypse – TV directed by Michael Engler/Saul Metzstein September 2014 Free Range Films Ltd, London Dialect/voice coach (Leeds): The Lady in the Van – Feature directed by Nicholas Hytner May 2014 Wilma TV, Inc. for Discovery Channel, New York Dialect Coach (Australian): Amerikan Kanibal - Docudrama February/March 2014 Mad As Birds Dialect Coach (Various Period US accents): Set Fire to the Stars - Feature directed by Andy Goddard February and June 2014 BBC 3 Dialect Coach (Liverpool and Australian): Crims - TV directed by James Farrell Dialect and Voice Coaching for theatre 2016 Oct 2016 Park Theatre, Dialect support (New York: Luv directed by Gary Condes Oct 2016 Kings Cross -

A Comprehensive Guide for Students (Aged 14+), Teachers & Arts

A Comprehensive Guide for students (aged 14+), teachers & arts educationalists Written by Scott Graham with contributions from the creative team Compiled by Frantic Assembly 1 How to read this pack When to read this pack This resource pack has been designed to be interactive This pack is designed to be read AFTER you have seen using Adobe Acrobat Reader and a has a number of the show. It contains some SPOILERS that would be a features built in to enhance your reading experience. great shame to divulge before seeing the production. Navigation You can navigate around the document in a number of ways 1 By clicking on the chapter menu bar at the top of each page 2 By clicking any entry on the contents and chapter opening pages 3 By clicking the arrows at the bottom of each page 4 By turning on Page Thumbnails in Acrobat Hyperlinks For further information, there are a number of hyperlinks which take you to external resources and are indicated by blue and underlined text or . Please note: You will need an internet connection to us this facility Ewan Stewart (Bob), Natalie Casey (Pip), Richard Mylan (Ben), Kirsty Oswald (Rosie). Video and Sound Photo Manuel Harlan There is a video and a soundclip embedded in the pack. You will need to click on the main image for the sound or video to play. You do not need an internet connection to use these facilities. 2 Contents How to read this pack 2 PROCESS 15 THEMES 40 When to read this pack 2 Process timeline 16 Running & Running (away from perfection) 41 Contents 3 From Nothing to Something: Bob & his -

Shakespeare, Jonson, and the Invention of the Author

11 Donaldson 1573 11/10/07 15:05 Page 319 SHAKESPEARE LECTURE Shakespeare, Jonson, and the Invention of the Author IAN DONALDSON Fellow of the Academy THE LIVES AND CAREERS OF SHAKESPEARE and Ben Jonson, the two supreme writers of early modern England, were intricately and curiously interwoven. Eight years Shakespeare’s junior, Jonson emerged in the late 1590s as a writer of remarkable gifts, and Shakespeare’s greatest theatri- cal rival since the death of Christopher Marlowe. Shakespeare played a leading role in the comedy that first brought Jonson to public promi- nence, Every Man In His Humour, having earlier decisively intervened— so his eighteenth-century editor, Nicholas Rowe, relates—to ensure that the play was performed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, who had ini- tially rejected the manuscript.1 Shakespeare’s name appears alongside that of Richard Burbage in the list of ‘principal tragedians’ from the same company who performed in Jonson’s Sejanus in 1603, and it has been con- jectured that he and Jonson may even have written this play together.2 During the years of their maturity, the two men continued to observe Read at the Academy 25 April 2006. 1 The Works of Mr William Shakespeare, ed. Nicholas Rowe, 6 vols. (London, printed for Jacob Tonson, 1709), I, pp. xii–xiii. On the reliability of Rowe’s testimony, see Samuel Schoenbaum, Shakespeare’s Lives (Oxford, 1970), pp. 19–35. 2 The list is appended to the folio text of the play, published in 1616. For the suggestion that Shakespeare worked with Jonson on the composition of Sejanus, see Anne Barton, Ben Jonson: Dramatist (Cambridge, 1984), pp.