Theatrical Exigency and Performative Politics in Trevor Nunn's Othello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

Rosena Hill Jackson Resume

ROSENA M. HILL JACKSON 941-350-8566 [email protected] www.RosenaHill.com BROADWAY/New York Carousel Nettie Jack O’Brien/Justin Peck Prince of Broadway swing Harold Prince/ Susan Stroman After Midnight Rosena Warren Carlyle/Daryl Waters/Wynton Marsalis Carousel Ensemble Avery Fisher Hall/PBS “Live at Lincoln Center” Cotton Club Parade Rosena Encores City Center Lost in the Stars Mrs. Mckenzie Encores Z City Center Come Fly Away Featured Vocalist Marriott Marqui Theatre/Twyla Tharp The Tin Pan Alley Rag Monisha/Miss Lee Roundabout Theatre Co./Stafford arima,dir Oscar Hammerstein II: The Song is You Soloist Carnegie Hall/New York Pops Color Purple Church Lady Broadway Theatre Spamalot Lady of the Lake/Standby Mike Nichols dir. Imaginary Friends Mrs. Stillman & others Jack O'Brien dir. Oklahoma Ellen Trevor Nunn mus dir./Susan Stroman chor. Riverdance on Broadway Amanzi Soloist Gershwin Theater Marie Christine Ozelia Graciela Daniele dir. Ragtime Sarah’s Friend u/s Frank Galati, Graciela Daniele/Ford’s Center REGIONAL The Toymaker Sarah NYMF/Lawrence Edelson,dir The World Goes Round Woman #1 Pittsburgh Public Theater/Marcia Milgrom Dodge,dir Ragtime Sarah White Plains Performing Arts Center Man of Lamancha Aldonza White Plains Performning Arts Center Baby Pam/s Papermill Playhouse Dreamgirls Michelle North Carolina Theater Ain’t Misbehavin’ Armelia Playhouse on the Green Imaginary Friends Smart women soloist Globe Theater 1001 Nights Sophie George Street Playhouse Mandela (with Avery Brooks) Winnie Steven Fisher dir./Crossroads Brief History -

PETER PAN Or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up

PRESS RELEASE NORTH HIGH SCHOOL to present PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up The Appleton North High School Theatre Department will present the play PETER PAN or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up on May 16th through the 19th in the North High School Auditorium, 5000 North Ballard Road. This new version adapted from the original J.M. Barrie play and novel by Trevor Nunn and John Caird for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre of London enjoyed phenomenal success when first produced. The famous team known for their productions of THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF NICHOLAS NICKLEBY and the musical LES MISERABLES have painstakingly researched and restored Barrie’s original play. “. .a national masterpiece.”—London Times. This is the beloved story of Peter, Wendy, Michael, John, Capt. Hook, Smee, the lost boys, pirates, and the Indians, and of course, Tinker Bell, in their adventures in Never Land. However, for the first time, the play is here restored to Barrie’s original intentions. In the words of adaptor, John Caird: “ We were fascinated to discover that there was no one single document called PETER PAN. What we found was a tantalizing number of different versions, all of them containing some very agreeable surprises….We have made some significant alterations, the greatest of which is the introduction of a new character, the Storyteller, who is in fact the author himself.” North’s theatre director, Ron Parker, states, “This is a very different PETER PAN than the one most people are familiar with. It is neither the popular musical version nor the Disney animated recreation, but goes back to Barrie’s original play and novel. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

Tippett a Child of Our Time

TIPPETT A CHILD OF OUR TIME Cynthia Haymon soprano Cynthia Clarey contralto London Symphony Chorus Damon Evans tenor London Symphony Orchestra Willard White bass Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Sir Michael Tippett (1905 – 1998) A Child of Our Time Part I 24:00 1 1 Chorus: ‘The world turns on its dark side’ 5:00 2 2 The Argument. Alto: ‘Man has measured the heavens with a telescope’ – Interludium 3:04 3 3 Scena. Chorus, Alto: ‘Is evil then good?’ 3:07 4 4 Bass (The Narrator): ‘Now in each nation there were some cast out...’ – 1:11 5 5 Chorus of the Oppressed: ‘When shall the usurers’ city cease...?’ 2:11 6 6 Tenor: ‘I have no money for my bread’ 3:26 7 7 Soprano: ‘How can I cherish my man in such days...?’ – 3:34 8 8 A Spiritual. Chorus, Soprano, Tenor: ‘Steal away’ 2:29 3 Part II 24:00 9 9 Chorus: ‘A star rises in mid-winter’ – 3:40 10 10 Bass (The Narrator): ‘And a time came...’ – 0:17 11 11 Double Chorus of Persecutors and Persecuted: ‘Away with them!’ – 0:57 12 12 Bass (The Narrator): ‘Where they could, they fled from the terror’ – 0:22 13 13 Chorus of the Self-righteous: ‘We cannot have them in our Empire’ – 0:49 14 14 Bass (The Narrator): ‘And the boy’s mother wrote a letter...’ 0:14 15 15 Scena. Solo Quartet (Mother, Aunt, Boy, Uncle): ‘O my son!’ – 1:29 16 16 A Spiritual. Chorus, Soprano, Tenor: ‘Nobody knows the trouble I see, Lord’ 1:17 17 17 Scena. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

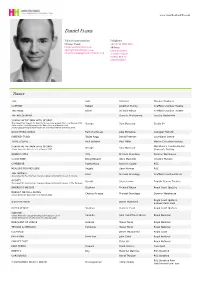

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Dialect and Voice

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Nov 16 – Feb 2017 Roseline Productions Dialect Coach for Will Ferrell, John C Reilly: Holmes and Watson Nov 2016 Sky Dialect Coach Bliss Nov 2016 BBC Dialect Coach for Zombie Boy: Silent Witness Aug 2016 Sky Dialect Coach for Iwan Rheon and Dimitri Leonidas: Riviera Jan/Feb 2016 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: ADR: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Oct 2015 Jellylegs/Sky 1 Dialect Coach: Rovers directed by Craig Cash Oct 2015 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Sept 2015 LittleRock Pictures/Sky Dialect /voice coach: Elizabeth, Michael and Marlon (Joseph Fiennes, Stockard Channing, Brian Cox) January – May 2015 BBC2/ITV, London Dialect Coach (East London): Cradle to Grave – directed by Sandy Johnson January – April 2015 Working Title/Sky Dialect Coach (Gen Am, Italian): You, Me and the Apocalypse – TV directed by Michael Engler/Saul Metzstein September 2014 Free Range Films Ltd, London Dialect/voice coach (Leeds): The Lady in the Van – Feature directed by Nicholas Hytner May 2014 Wilma TV, Inc. for Discovery Channel, New York Dialect Coach (Australian): Amerikan Kanibal - Docudrama February/March 2014 Mad As Birds Dialect Coach (Various Period US accents): Set Fire to the Stars - Feature directed by Andy Goddard February and June 2014 BBC 3 Dialect Coach (Liverpool and Australian): Crims - TV directed by James Farrell Dialect and Voice Coaching for theatre 2016 Oct 2016 Park Theatre, Dialect support (New York: Luv directed by Gary Condes Oct 2016 Kings Cross -

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare

Shakespeare, William Shakespeare. Julius Caesar The Shakespeare Ralph Richardson, Anthony SRS Caedmon 3 VG/ Text Recording Society; Quayle, John Mills, Alan Bates, 230 Discs VG+ Howard Sackler, dir. Michael Gwynn Anthony And The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cleopatra Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 235 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Great Scenes The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Pamela Brown, TC- Caedmon 1 VG/ Text from Recording Society; Paul Daneman, Jack Gwillim 1183 Disc VG+ Anthony And Howard Sackler, dir. Cleopatra Titus The Shakespeare Anthony Quayle, Maxine SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Andronicus Recording Society; Audley, Michael Horden, Colin 227 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Blakely, Charles Gray Pericles The Shakespeare Paul Scofield, Felix Aylmer, Judi SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Dench, Miriam Karlin, Charles 237 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Gray Cymbeline The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Boris Karloff, SRS- Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Recording Society; Pamela Brown, John Fraser, M- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. Alan Dobie 236 The Comedy The Shakespeare Alec McCowen, Anna Massey, SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Of Errors Recording Society; Harry H. Corbett, Finlay Currie 205- Discs Howard Sackler, dir. S Venus And The Shakespeare Claire Bloom, Max Adrian SRS Caedmon 2 VG+ Text Adonis and A Recording Society; 240 Discs Lover's Howard Sackler, dir. Complaint Troylus And The Shakespeare Diane Cilento, Jeremy Brett, SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text Cressida Recording Society; Cyril Cusack, Max Adrian 234 Discs Howard Sackler, dir. King Richard The Shakespeare John Gielgud, Keith Michell and SRS Caedmon 3 VG+ Text II Recording Society; Leo McKern 216 Discs Peter Wood, dir. -

A Comprehensive Guide for Students (Aged 14+), Teachers & Arts

A Comprehensive Guide for students (aged 14+), teachers & arts educationalists Written by Scott Graham with contributions from the creative team Compiled by Frantic Assembly 1 How to read this pack When to read this pack This resource pack has been designed to be interactive This pack is designed to be read AFTER you have seen using Adobe Acrobat Reader and a has a number of the show. It contains some SPOILERS that would be a features built in to enhance your reading experience. great shame to divulge before seeing the production. Navigation You can navigate around the document in a number of ways 1 By clicking on the chapter menu bar at the top of each page 2 By clicking any entry on the contents and chapter opening pages 3 By clicking the arrows at the bottom of each page 4 By turning on Page Thumbnails in Acrobat Hyperlinks For further information, there are a number of hyperlinks which take you to external resources and are indicated by blue and underlined text or . Please note: You will need an internet connection to us this facility Ewan Stewart (Bob), Natalie Casey (Pip), Richard Mylan (Ben), Kirsty Oswald (Rosie). Video and Sound Photo Manuel Harlan There is a video and a soundclip embedded in the pack. You will need to click on the main image for the sound or video to play. You do not need an internet connection to use these facilities. 2 Contents How to read this pack 2 PROCESS 15 THEMES 40 When to read this pack 2 Process timeline 16 Running & Running (away from perfection) 41 Contents 3 From Nothing to Something: Bob & his