Memory and Narratives in Science Communication 3 Aquiles Negrete 4 5 6 ‘Every Man’S Memory Is His Private Literature’ 7 Aldous Huxley 8 9 Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Memory Techniques

20 Memory Techniques Experiment 1,viththese techniques to develop a.flexible, custom-made memm}" system that fits your stJ:fe qf learning the content <ifyour courses and the skills <~/'your,sport. 17w 20 techniques are divided intnfour categories, each 1-vhichrepresents a general principlefiJr improving mem.ory. Organize it 1. Be selective. To a large degree, the art of memory is the a,t of selecting what to remember in the first place. As you dig into your textbooks, playbooks. and notes, make choices about what is most important to learn. Imagine that you are going to create a test on the material and consider the questions you would ask. When reading, look for chapter previews, summaries, and review questions. Pay attention to anything printed in bold type. A !so notice visual elements, such as charts, graphs, and illustrations. All of these are clues pointing to what's important. During lectures, notice what the instructor emphasizes. During practice, focus on what your coach requires you to repeat. Anything that presented visually-on the board, on overheads, or with slides-is also key. 2. Make it meaningful. One way to create meaning is to learn from the general to the specific. Before tackling the details, get the big picture. Before you begin your next reading assignment, for example, skim it lo locate the main idea. If you're ever lost, step back and recall that idea. The details might make more sense. You can also organize any list of items-even random ones-in a meaningful way to make them easier to remember. -

Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement Or Self-Depletion?

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 05 April 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00469 Memory-Modulation: Self-Improvement or Self-Depletion? Andrea Lavazza* Neuroethics, Centro Universitario Internazionale, Arezzo, Italy Autobiographical memory is fundamental to the process of self-construction. Therefore, the possibility of modifying autobiographical memories, in particular with memory-modulation and memory-erasing, is a very important topic both from the theoretical and from the practical point of view. The aim of this paper is to illustrate the state of the art of some of the most promising areas of memory-modulation and memory-erasing, considering how they can affect the self and the overall balance of the “self and autobiographical memory” system. Indeed, different conceptualizations of the self and of personal identity in relation to autobiographical memory are what makes memory-modulation and memory-erasing more or less desirable. Because of the current limitations (both practical and ethical) to interventions on memory, I can Edited by: only sketch some hypotheses. However, it can be argued that the choice to mitigate Rossella Guerini, painful memories (or edit memories for other reasons) is somehow problematic, from an Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Italy ethical point of view, according to some of the theories of the self and personal identity Reviewed by: in relation to autobiographical memory, in particular for the so-called narrative theories Tillmann Vierkant, University of Edinburgh, of personal identity, chosen here as the main case of study. Other conceptualizations of United Kingdom the “self and autobiographical memory” system, namely the constructivist theories, do Antonella Marchetti, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, not have this sort of critical concerns. -

Elaborative Encoding, the Ancient Art of Memory, and the Hippocampus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2013) 36, 589–659 provided by RERO DOC Digital Library doi:10.1017/S0140525X12003135 Such stuff as dreams are made on? Elaborative encoding, the ancient art of memory, and the hippocampus Sue Llewellyn Faculty of Humanities, University of Manchester, Manchester M15 6PB, United Kingdom http://www.humanities.manchester.ac.uk [email protected] Abstract: This article argues that rapid eye movement (REM) dreaming is elaborative encoding for episodic memories. Elaborative encoding in REM can, at least partially, be understood through ancient art of memory (AAOM) principles: visualization, bizarre association, organization, narration, embodiment, and location. These principles render recent memories more distinctive through novel and meaningful association with emotionally salient, remote memories. The AAOM optimizes memory performance, suggesting that its principles may predict aspects of how episodic memory is configured in the brain. Integration and segregation are fundamental organizing principles in the cerebral cortex. Episodic memory networks interconnect profusely within the cortex, creating omnidirectional “landmark” junctions. Memories may be integrated at junctions but segregated along connecting network paths that meet at junctions. Episodic junctions may be instantiated during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep after hippocampal associational function during REM dreams. Hippocampal association involves relating, binding, and integrating episodic memories into a mnemonic compositional whole. This often bizarre, composite image has not been present to the senses; it is not “real” because it hyperassociates several memories. During REM sleep, on the phenomenological level, this composite image is experienced as a dream scene. -

Memory in Mind and Culture

This page intentionally left blank Memory in Mind and Culture This text introduces students, scholars, and interested educated readers to the issues of human memory broadly considered, encompassing individual mem- ory, collective remembering by societies, and the construction of history. The book is organized around several major questions: How do memories construct our past? How do we build shared collective memories? How does memory shape history? This volume presents a special perspective, emphasizing the role of memory processes in the construction of self-identity, of shared cultural norms and concepts, and of historical awareness. Although the results are fairly new and the techniques suitably modern, the vision itself is of course related to the work of such precursors as Frederic Bartlett and Aleksandr Luria, who in very different ways represent the starting point of a serious psychology of human culture. Pascal Boyer is Henry Luce Professor of Individual and Collective Memory, departments of psychology and anthropology, at Washington University in St. Louis. He studied philosophy and anthropology at the universities of Paris and Cambridge, where he did his graduate work with Professor Jack Goody, on memory constraints on the transmission of oral literature. He has done anthro- pological fieldwork in Cameroon on the transmission of the Fang oral epics and on Fang traditional religion. Since then, he has worked mostly on the experi- mental study of cognitive capacities underlying cultural transmission. After teaching in Cambridge, San Diego, Lyon, and Santa Barbara, Boyer moved to his present position at the departments of anthropology and psychology at Washington University, St. Louis. James V. -

VIVEKANANDA and the ART of MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1

VIVEKANANDA AND THE ART OF MEMORY June 26, 1994 M. Ram Murty, FRSC1 1. Episodes from Vivekananda’s life 2. Episodes from Ramakrishna’s life 3. Their memory power compared by Swami Saradananda 4. Other srutidharas from the past 5. The ancient art of memory 6. The laws of memory 7. The role of memory in daily life Episodes from Vivekananda’s life The human problem is one of memory. We have forgotten our divine nature. All the great teachers of the past have declared that the revival of the memory of our divinity is the paramount goal. Memory is a faculty and as such, it is neither good nor bad. Every action that we do, every thought that we think, leaves an indelible trail of memory. Whether we remember or not, the contents are recorded and affect our daily life. Therefore, an awareness of this faculty and its method of operation is vital for healthy existence. Properly employed, it leads us to enlightenment; abused or misused, it can torment us. So we must learn to use it properly, to strengthen it for our own improvement. In studying the life of Vivekananda, we come across many phenomenal examples of his amazing faculty of memory. In ‘Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda,’ Haripada Mitra relates the following story: One day, in the course of a talk, Swamiji quoted verbatim some two or three pages from Pickwick Papers. I wondered at this, not understanding how a sanyasin could get by heart so much from a secular book. I thought that he must have read it quite a number of times before he took orders. -

The Pulpit & the Memory Palace

Copyright by Ryan Tinetti 2019 !iii THESIS ABSTRACT The following thesis considers the benefits of classical rhetoric for contemporary preaching, with special reference to the classical memorization technique known as the method of loci (or Memory Palace). The goal for this research is to discern how the method of loci can help pastors to “preach by heart,” that is, to internalize the sermon such that they can preach it without notes as though it were an extemporaneous Spirit- prompted utterance. To this end, the thesis is structured around two parts. Following an Introduction that sets out the practical challenges to preaching by heart that attend many pastors, Part 1 provides a survey of classical rhetoric, especially the so-called “modes of persuasion” and “canons of rhetoric,” before then turning specifically to the canon of Memoria (“memory”) and its concomitant practice of the Memory Palace. Part 2 applies the insights of the first part to the process of sermon preparation more broadly, and then walks through the practice of the Memory Palace for preaching in particular. A Conclusion recapitulates the argument and demonstrates the method of loci in practice. !iv To Anne, who knows me by heart !v TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Acknowledgements vii Introduction: Preaching by Heart 1 Part 1: Classical Rhetoric and the Method of Loci 22 Chapter 1: An Overview of Classical Rhetoric 23 Chapter 2: Memoria and the Method of Loci 43 Part 2: Contemporary Preaching and the Memory Palace 64 Chapter 3: Applying Classical Rhetoric to Sermon Preparation 65 Chapter 4: Constructing the Memory Palace 79 Conclusion: At Home in the Word 104 Bibliography 122 Biography 127 !vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To complete a project such as this thesis is to create a profound sense of indebtedness and gratitude to the many people who made it possible. -

Moonwalking with Einstein

Moonwalking With Einstein jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj Let’s Connect! jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjj jjjjjjjjjjjjjj Moonwalking With Einstein, Joshua Foer My Rating (From 0-5) Complexity (From 0-10) 5 Summary What makes an expert? Is it the amount of years they have under their belt? Or a specific certification? In this book, Joshua Foer will challenge our preconceived notions of expertise. He’ll show us how the tops in each field aren’t just better because they’ve been there long enough, or have the certifications, but instead because they’ve trained their memory to hold enough valuable memories so that when a situation presents they rely on intuition rather than analysis. My Takeaway In the coming future algorithms will fundamentally transform the world we see today. From analysis based fields like accounting to finance, to creative fields like journalism, nursing, you name it and algorithms will have more value than humans in each job role. But it’s not all doom and gloom. What the algorithms can’t do, and will never do (we think), is replace the inherent intuition each of us has. These are the big ideas, the solutions that seem out of nowhere and come about in split seconds. The author points to stories of experts in SWAT, and how they can sense danger ten seconds before any of the entry or mid-level officers. He also supports this with the best chess players. No matter the niche, each expert pulls from intuition, from long term memory, NOT analysis – what the computer can do. -

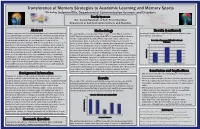

Transference of Memory Strategies to Academic Learning and Memory

Transference of Memory Strategies to Academic Learning and Memory Sports Nicholas Solomon Ellis, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders Faculty Sponsors Drs. Crystal Randolph, & Ruth Renee Hannibal Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders Abstract Methodology Results (continued) Memory is the process of recalling what has been learned and retained The participant is a college student who began to learn MTs in September memory techniques were higher for the memory games than especially through associative mechanisms. Anatomically, this includes 2015. The participant initially learned the MTs to learn Spanish vocabulary the academic assessment. electrical impulses fired in our brains to relay information. When we and then subsequently used the MTs to help learn course content. The learn new information, we use our memories to help recall the participant was given 2 tasks, one academic learning assessment and 2 Percentage of Responses Attributable to Memory information stored in our brains. Without memory, there is no access to Techniques memory sports games. The academic learning assessment was created by a 120 using stored information. Mnemonics are techniques used to improve professor in the participant’s major department and included 12 questions and enhance memory. Other memory techniques include but are not from content learned in courses taken Fall 2015. The questions were 100 s e s limited to, the method of loci, peg systems, and phonetic systems. n 80 developed based on Bloom’s taxonomy and were related to language o p s E From these systems spawned competitions, memory sports, which R development, phonetics, and general knowledge of CSD. Each section f o 60 e g have created remarkable feats of memorization. -

A Brief History of Memory and Aging

7 A Brief History of Memory and Aging AIMÉE M. SURPRENANT, TAMRA J. BIRETA, and LISA A. FARLEY n addition to his empirical work, Roddy Roediger has written tutorials, commentaries, encyclopedia articles, summaries of entire areas, textbooks, I practical guides to research, career guides, and guides to professional devel- opment. Throughout all of his work there is a clear sensitivity to history. He has written and given talks on the works of Ebbinghaus, Bartlett, Ballard, Deese, Nipher, and others, and, through his many editorships, he has supported the efforts of others in this direction. Even though he is no longer the editor, Psycho- nomic Bulletin and Review, a journal Roddy reinvented, is known to welcome submissions exploring the history of experimental psychology. If that were not enough, in recent years Roddy’s research program has added a new facet, exploring age-related differences in memory, particularly as it concerns false memory. Thus, it seemed appropriate to combine those interests and delve into the history of memory and aging at the conference in his honor. The purpose of this chapter, therefore, is to summarize the history of beliefs and research that serves as the foundation of current work on memory and aging. Although there have been in-depth articles on the history of life-span develop- mental psychology (Baltes, 1983), histories and surveys of the psychology of aging (Birren, 1961a, 1961b; Birren & Schroots, 2001; Granick, 1950; Pressey, Janney, & Kuhlen, 1939), and comprehensive considerations of the history of memory (e.g., Burnham, 1888; Murray, 1976; Yates, 1966), there is no published look into the history of aging and memory specifically. -

The Arts of Memory Comparative Perspectives on a Mental Artifact

2012 | HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2 (2): 451–85 |Translation| The arts of memory Comparative perspectives on a mental artifact Carlo SEVERI, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Revised and updated by the author Translated from the French by Matthew Carey For linguists, anthropologists and archaeologists, the emblematic image always and everywhere preceded the appearance of the sign. This myth of a figurative language composed by icons—that form the opposite figure of writing—has deeply influenced Western tradition. In this article, I show that the logic of Native American Indian mnemonics (pictographs, khipus) cannot be understood from the ethnocentric question of the comparison with writing, but requires a truly comparative anthropology. Rather than trying to know if Native American techniques of memory are true scripts or mere mnemonics, we can explore the formal aspect both have in common, compare the mental processes they call for. We can ask if both systems belong to the same conceptual universe, to a mental language—to use Giambattista Vico’s phrase—that would characterize the Native American arts of memory. In this perspective, techniques of memory stop being hybrids or imprecise, and we will better understand their nature and functions as mental artifacts. Keywords: art, memory, pictographs, khipu, tradition, iconography There must in the nature of human things be a mental language common to all nations. This axiom is the principle of the hieroglyphs by which all nations spoke in the time of their first barbarism. Giambattista Vico, La scienza nuova, [1744] 1990 Social memory necessarily involves the remembrance of origins. -

Visualizing Words and Knowledge: Arts of Memory from the Agora to the Computer

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2015 Visualizing Words and Knowledge: Arts of Memory from the Agora to the Computer Seth D. Long Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Long, Seth D., "Visualizing Words and Knowledge: Arts of Memory from the Agora to the Computer" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 222. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/222 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines rhetoric’s fourth canon—the art of memory—tracing its development through the classical, medieval, and early modern periods. It argues that for most of its history, the fourth canon was an art by which words and knowledge were remediated into visual, spatial forms, either in the mind or on the page. And it was this technique of visualization, I argue, that linked the canons of memory and invention throughout history. In contemporary rhetorical theory, however, memory palaces and mnemonic imagery have been replaced with a conception of memory grounded in psychology and critique. I argue that this move away from memory as an artificial practice has obscured the classical art’s visual precepts, consequently severing the ancient link between memory and invention. I suggest that contemporary rhetorical theorists should return to visualization to revitalize the fourth canon in the twenty-first century. Today, digital tools that visualize words and knowledge are ubiquitous. -

Effects of Eye-Closure & Schematic Information on Memory Accuracy

Page 1 of 19 Effects of Eye-Closure & Schematic Information on Memory Accuracy & Confidence in a Witness Testimony Situation Manal Almugathwi Supervised by: Andrew Parker April 2016 Page 2 of 19 Effects of Eye-Closure & Schematic Information on Memory Accuracy & Confidence in a Witness Testimony Situation ABSTRACT The aim of the current study is to investigate the effects of eye-closure on true and false memory for schematic and non-schematic information. Sixty-four participants were presented with a narrative concerning a bank robbery; within this, information was provided that was highly prototypical (schematic) or non- prototypical (non-schematic) of a robbery. After a delay, memory was assessed with eyes open or eyes closed. The memory test consisted of an item recognition task for events followed by a confidence scale. The items on the test consisted of either studied or non-studied information, which was either schematic or non- schematic. It is hypothesised that (i) eye-closure will reduce false memory and increase true memory accuracy, and (ii) the eye condition will interact with the prototypically of the information. In addition, it is predicted that confidence ratings will mirror the effects of memory accuracy. The findings do not support the hypothesis that predicted that true memory accuracy and confidence would be enhanced and false memory would be reduced following eye-closure. However, the hypothesis that true and false memory would be related to schema relevance was supported. Greater memory recall was reported for studied schema-relevant items (irrespective of eye condition). However, higher false alarms was reported for non-studied schema-relevant items (greater false memory).