Mnemonic Influence 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Conditioning Without Awareness: an Electrophysiological Investigation

Classical conditioning without awareness: An electrophysiological investigation A Thesis Presented to The Division of Philosophy, Religion, Psychology, and Linguistics Reed College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts Jasmine Huang December 2016 Approved for the Division (Psychology) Timothy Hackenberg Michael Pitts Acknowledgements There is no way to express the amount of gratitude I feel towards every single person who has contributed to my growth as a student and as a human being, but I will try. My family, who has worked tirelessly to support me through life and years of school, I will never know how to repay that debt. My advisors, who have endlessly encouraged me and provided me with every opportunity I could have wished for. Tim who has believed in and supported me from my first year at Reed right up until the end. Enriqueta who was always willing to discuss experiments outside of class (even when I wasn’t in her class to begin with). Michael who inspired me every day with his unending enthusiasm and drive for research. The amazing psychology department staff who are always making sure that everything is running as smoothly as it can be. Joan, our silent hero who puts out the metaphorical fires every day. Greg, one the most lively presences in the animal colony, whose love for all of the critters is unparalleled. Chris, whose attention to detail and patience for dumb questions were invaluable to me during this process. Lavinia, whose realism and dark humor made for the best introduction into real labwork that I could have asked for. -

*For All Comprehensive Exam Sections, DO NOT Attempt Answering a Question Unless You Really Know the Answer

*For all comprehensive exam sections, DO NOT attempt answering a question unless you really know the answer. You will be much less likely to pass if you provide information that does not actually address a question (even if the information you provide is technically accurate, and could be used to answer another question). Also, most questions (except Statistics) will require you to cite original sources to support your arguments, but please do not cite a textbook. Cognition and Learning Section This exam is tied most directly to PSY 620 and 621. You are not allowed to attempt this exam until you have passed both of these courses. You will see questions covering such topics as (in no particular order of importance): perception, attention, working memory, episodic versus semantic versus procedural long- term memory, implicit versus explicit memory, automatic versus controlled processing, categorization, social cognition, metacognition, theories of learning and behavior, eyewitness memory, language, decision-making and problem-solving, expertise, and developmental/age issues concerning memory. By far the most important thing to study is an undergraduate textbook in cognitive psychology (e.g., Goldstein; Reisberg; Robinson-Riegler; Sternberg), as well as notes and materials from PSY 620. Below is an example question (no longer used) with a good student response. It will give you an idea of the level of detail needed for a good response, and how to cite original sources to support your statements. You are an eyewitness to a crime in which a man robs a liquor store. He does so in under 5 minutes while pointing a gun at the clerk, is not wearing a mask or anything else to hide his face, and he quickly runs away after the robbery. -

Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective

Review Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective 1, 2 3 William Hirst, * Jeremy K. Yamashiro, and Alin Coman Social scientists have studied collective memory for almost a century, but psy- Highlights chological analyses have only recently emerged. Although no singular approach Collective memories can involve small communities, such as couples, to the psychological study of collective memory exists, research has largely: (i) families, or neighborhood associa- exploredthe social representations of history, including generational differences; tions, or large communities, such as nations, the world-wide congregation (ii) probed for the underlying cognitive processes leading to the formation of of Catholics, or terrorist groups such collective memories, adopting either a top-down or bottom-up approach; and (iii) as ISIS. They bear on the collective explored how people live in history and transmit personal memories of historical identity of the community. importance acrossgenerations.Here,wediscussthesedifferent approaches and Many studies focus on either the repre- highlight commonalities and connections between them. sentation of extant collective memories or the formation and retention of either extant or new collective memories. Memories Held Across a Community Members of a community often share similar memories: Germans know that their country Those interested in the formation of participated in the mass murder of Jews; Catholics, that Jesus fasted for 40 days; and a family, collective memories can approach ’ that grandfather immigrated from Ireland. Such collective memories can shape a community s the topic in a top-down or bottom- up fashion. ’ identity and its actions. Germany s struggles to come to terms with its troublesome past, for fi instance, de ne to a great extent how Germans see themselves today as Germans [1]. -

20 Memory Techniques

20 Memory Techniques Experiment 1,viththese techniques to develop a.flexible, custom-made memm}" system that fits your stJ:fe qf learning the content <ifyour courses and the skills <~/'your,sport. 17w 20 techniques are divided intnfour categories, each 1-vhichrepresents a general principlefiJr improving mem.ory. Organize it 1. Be selective. To a large degree, the art of memory is the a,t of selecting what to remember in the first place. As you dig into your textbooks, playbooks. and notes, make choices about what is most important to learn. Imagine that you are going to create a test on the material and consider the questions you would ask. When reading, look for chapter previews, summaries, and review questions. Pay attention to anything printed in bold type. A !so notice visual elements, such as charts, graphs, and illustrations. All of these are clues pointing to what's important. During lectures, notice what the instructor emphasizes. During practice, focus on what your coach requires you to repeat. Anything that presented visually-on the board, on overheads, or with slides-is also key. 2. Make it meaningful. One way to create meaning is to learn from the general to the specific. Before tackling the details, get the big picture. Before you begin your next reading assignment, for example, skim it lo locate the main idea. If you're ever lost, step back and recall that idea. The details might make more sense. You can also organize any list of items-even random ones-in a meaningful way to make them easier to remember. -

Reducing False Memories Chad S

MacLeod and MacDonald – The Stroop effect and attention Review 17 Dunbar, K.N. and MacLeod, C.M. (1984) A horse race of a different 28 Carter, C.S. et al. (2000) Parsing executive processes: strategic versus color: Stroop interference patterns with transformed words. J. Exp. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 10, 622–639 Sci. U. S. A. 97, 1944–1948 18 Fraisse, P. (1969) Why is naming longer than reading? Acta Psychol. 29 Derbyshire, S.W.G. et al. (1998) Pain and Stroop interference activate 30, 96–103 separate processing modules in anterior cingulate. Exp. Brain Res. 19 Kolers, P.A. (1975) Memorial consequences of automatized encoding. 118, 52–60 J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 1, 689–701 30 Bush, G. et al. (2000) Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior 20 Tzelgov, J. et al. (1992) Controlling Stroop effects by manipulating cingulate cortex. Trends Cognit. Sci. 4, 215–222 expectations for color words. Mem. Cognit. 20, 727–735 31 Corbetta, M. et al. (1991) Selective and divided attention during visual 21 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. (1981) P300 latency: a new metric of discriminations of shape, color, and speed: functional anatomy by information processing. Psychophysiology 18, 207–215 positron emission tomography. J. Neurosci. 11, 2383–2402 22 Duncan-Johnson, C.C. and Kopell, B.S. (1981) The Stroop effect: brain 32 Petersen, S.E. et al. (1988) Positron emission tomographic studies potentials localize the source of interference. Science 214, 938–940 of the cortical anatomy of single-word processing. Nature 23 Bench, C.J. -

What Is It Like to Be Confabulating?

What is it like to be Confabulating? Sahba Besharati, Aikaterini Fotopoulou and Michael D. Kopelman Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London UK Different kinds of confabulations may arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. This chapter first offers conceptual distinctions between spontaneous and momentary (“provoked”) confabulations, as well as between these types of confabulation and other kinds of false memories. The chapter then reviews current explanatory theories, emphasizing that both neurocognitive and motivational factors account for the content of confabulations. We place particular emphasis on a general model of confabulation that considers cognitive dysfunctions in memory and executive functioning in parallel with social and emotional factors. It is argued that all these dimensions need to be taken into account for a phenomenologically rich description of confabulation. The role of the motivated content of confabulation and the subjective experience of the patient are particularly relevant in effective management and rehabilitation strategies. Finally, we discuss a case example in order to illustrate how seemingly meaningless false memories are actually meaningful if placed in the context of the patient’s own perspective and autobiographical memory. Key words: Confabulation; False memory; Motivation; Self; Rehabilitation. 1 Memory is often subject to errors of omission and commission such that recollection includes instances of forgetting, or distorting past experience. The study of pathological forms of exaggerated memory distortion has provided useful insights into the mechanisms of normal reconstructive remembering (Johnson, 1991; Kopelman, 1999; Schacter, Norman & Kotstall, 1998). An extreme form of pathological memory distortion is confabulation. Different variants of confabulation are found to arise in neurological and psychiatric disorders. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

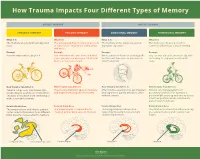

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: the Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories

Psychology and Aging Copyright 2002 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2002, Vol. 17, No. 4, 636–652 0882-7974/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.4.636 Emotionally Charged Autobiographical Memories Across the Life Span: The Recall of Happy, Sad, Traumatic, and Involuntary Memories Dorthe Berntsen David C. Rubin University of Aarhus Duke University A sample of 1,241 respondents between 20 and 93 years old were asked their age in their happiest, saddest, most traumatic, most important memory, and most recent involuntary memory. For older respondents, there was a clear bump in the 20s for the most important and happiest memories. In contrast, saddest and most traumatic memories showed a monotonically decreasing retention function. Happy involuntary memories were over twice as common as unhappy ones, and only happy involuntary memories showed a bump in the 20s. Life scripts favoring positive events in young adulthood can account for the findings. Standard accounts of the bump need to be modified, for example, by repression or reduced rehearsal of negative events due to life change or social censure. Many studies have examined the distribution of autobiographi- (1885/1964) drew attention to conscious memories that arise un- cal memories across the life span. No studies have examined intendedly and treated them as one of three distinct classes of whether this distribution is different for different classes of emo- memory, but did not study them himself. In his well-known tional memories. Here, we compare the event ages of people’s textbook, Miller (1962/1974) opened his chapter on memory by most important, happiest, saddest, and most traumatic memories quoting Marcel Proust’s description of how the taste of a Made- and most recent involuntary memory to explore whether different leine cookie unintendedly brought to his mind a long-forgotten kinds of emotional memories follow similar patterns of retention. -

Comparison Between Two Methodological Paradigms of Conditioned Place Preference with Methlyphenidate

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 12-2013 Comparison between Two Methodological Paradigms of Conditioned Place Preference with Methlyphenidate. Bryce D. Watson East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Bryce D., "Comparison between Two Methodological Paradigms of Conditioned Place Preference with Methlyphenidate." (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 89. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/89 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Watson 1 Comparison between Two Methodological Paradigms of Conditioned Place Preference with Methlyphenidate By Bryce Watson The Honors College Honors in Discipline Program East Tennessee State University Department of Psychology December 9, 2013 Russell Brown, Faculty Mentor David Harker, Faculty Reader Eric Sellers, Faculty Reader Watson 2 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to examine the mechanisms of Methylphenidate (MPH) on Conditioned Place Preference (CPP), a behavioral test of reward. The psychostimulant MPH is therapeutically used in the treatment of ADHD, but has been implicated in many pharmacological actions related to drug addiction and is considered to have abuse potential. Past work in our lab and others have shown substantial sex-differences in the neuropharmacological profile of MPH. Here a discussion of the relevant mechanisms of action of MPH and its relationship to neurotrophins and CPP are reviewed. -

Webinar Lecture #5

5/20/20 Foundations for Integrating Hypnosis into Your Therapies for Treating Anxiety, Depression, and Pain with Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. Webinar Section 5 of 12 Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 1 • Direct regression to a specific time, context • Imagery of special vehicles • Metaphorical and indirect approaches Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 2 • Orient to hypnosis • Induction • Response set regarding memory • Regression strategy; emphasize positive memory • Interaction (remember to ask neutrally) • PHS (integrate a positive learning from the experience) • Closure and disengagement Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 3 1 5/20/20 •Encoding •Storage •Retrieval Distortions can occur at any stage Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 4 “Memory is reconstructive, not reproductive” Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 5 “I have the feeling…but I don’t have the memory” Stage hypnosis: “What’s so funny about your movie?” Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 6 2 5/20/20 That’s why hypnotically obtained testimony is generally excluded from court proceedings In Search of Memory by Eric Kandel Searching for Memory by Daniel Schacter The Seven Sins of Memory by Daniel Schacter The Memory Illusion by Julia Shaw Memory by Bennett Schwartz Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 8 And a whole new generation of therapists is starting to make some of the same mistakes all over again… Michael D. Yapko, Ph.D. www.yapko.com 9 3 5/20/20 See “Divided Memories,” a PBS 4-hour documentary on the subject you’ll find on YouTube Also watch the demonstration of implanting a false memory on YouTube by Dr. -

Serial Position Effects and Forgetting Curves: Implications in Word

Studies in English Language Teaching ISSN 2372-9740 (Print) ISSN 2329-311X (Online) Vol. 2, No. 3, 2014 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/selt Original Paper Serial Position Effects and Forgetting Curves: Implications in Word Memorization Guijun Zhang1* 1 Department of Foreign Languages, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China * Guijun Zhang, E-mail:[email protected] Abstract Word memorization is important in English learning and teaching. The theory and implications of serial position effects and forgetting curves are discussed in this paper. It is held that they help students understand the psychological mechanisms underlying word memorization. The serial position effects make them to consider the application the chunking theory in word memorization; the forgetting curve reminds them to repeat the words in long-term memory in proper time. Meanwhile the spacing effect and elaborative rehearsal effect are also discussed as they are related to the forgetting curve. Keywords serial position effects, forgetting curves, word memorization 1. Introduction English words are extraordinarily significant for English foreign language (EFL) learners because they are the essential basis of all language skills. As Wilkins said, “...while without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” (Wilkins, 1972). Effective word memorization plays a significant role in the process of vocabulary learning. Researchers have and are still pursuing and summarizing the effective memory methods. Schmitt, for example, classified vocabulary memory strategies into more than twenty kinds (Schmitt, 1997, p. 34). However, it is hard to improve the efficiency of the vocabulary memory in that different students remember the huge amount of words with some certain method or methods that may not suit them.