Anti-Doping Tribunal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2021 List of Pharmacological Classes of Doping Agents and Doping Methods

BGBl. III - Ausgegeben am 8. Jänner 2021 - Nr. 1 1 von 23 The 2021 list of pharmacological classes of doping agents and doping methods www.ris.bka.gv.at BGBl. III - Ausgegeben am 8. Jänner 2021 - Nr. 1 2 von 23 www.ris.bka.gv.at BGBl. III - Ausgegeben am 8. Jänner 2021 - Nr. 1 3 von 23 THE 2021 PROHIBITED LIST WORLD ANTI-DOPING CODE DATE OF ENTRY INTO FORCE 1 January 2021 Introduction The Prohibited List is a mandatory International Standard as part of the World Anti-Doping Program. The List is updated annually following an extensive consultation process facilitated by WADA. The effective date of the List is 1 January 2021. The official text of the Prohibited List shall be maintained by WADA and shall be published in English and French. In the event of any conflict between the English and French versions, the English version shall prevail. Below are some terms used in this List of Prohibited Substances and Prohibited Methods. Prohibited In-Competition Subject to a different period having been approved by WADA for a given sport, the In- Competition period shall in principle be the period commencing just before midnight (at 11:59 p.m.) on the day before a Competition in which the Athlete is scheduled to participate until the end of the Competition and the Sample collection process. Prohibited at all times This means that the substance or method is prohibited In- and Out-of-Competition as defined in the Code. Specified and non-Specified As per Article 4.2.2 of the World Anti-Doping Code, “for purposes of the application of Article 10, all Prohibited Substances shall be Specified Substances except as identified on the Prohibited List. -

Drug Testing Program

DRUG TESTING PROGRAM Copyright © 2021 CrossFit, LLC. All Rights Reserved. CrossFit is a registered trademark ® of CrossFit, LLC. 2021 DRUG TESTING PROGRAM 2021 DRUG TESTING CONTENTS 1. DRUG-FREE COMPETITION 2. ATHLETE CONSENT 3. DRUG TESTING 4. IN-COMPETITION/OUT-OF-COMPETITION DRUG TESTING 5. REGISTERED ATHLETE TESTING POOL (OUT-OF-COMPETITION DRUG TESTING) 6. REMOVAL FROM TESTING POOL/RETIREMENT 6A. REMOVAL FROM TESTING POOL/WATCH LIST 7. TESTING POOL REQUIREMENTS FOLLOWING A SANCTION 8. DRUG TEST NOTIFICATION AND ADMINISTRATION 9. SPECIMEN ANALYSIS 10. REPORTING RESULTS 11. DRUG TESTING POLICY VIOLATIONS 12. ENFORCEMENT/SANCTIONS 13. APPEALS PROCESS 14. LEADERBOARD DISPLAY 15. EDUCATION 16. DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS 17. TRANSGENDER POLICY 18. THERAPEUTIC USE EXEMPTION APPENDIX A: 2020-2021 CROSSFIT BANNED SUBSTANCE CLASSES APPENDIX B: CROSSFIT URINE TESTING PROCEDURES - (IN-COMPETITION) APPENDIX C: TUE APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS Drug Testing Policy V4 Copyright © 2021 CrossFit, LLC. All Rights Reserved. CrossFit is a registered trademark ® of CrossFit, LLC. [ 2 ] 2021 DRUG TESTING PROGRAM 2021 DRUG TESTING 1. DRUG-FREE COMPETITION As the world’s definitive test of fitness, CrossFit Games competitions stand not only as testaments to the athletes who compete but to the training methodologies they use. In this arena, a true and honest comparison of training practices and athletic capacity is impossible without a level playing field. Therefore, the use of banned performance-enhancing substances is prohibited. Even the legal use of banned substances, such as physician-prescribed hormone replacement therapy or some over-the-counter performance-enhancing supplements, has the potential to compromise the integrity of the competition and must be disallowed. With the health, safety, and welfare of the athletes, and the integrity of our sport as top priorities, CrossFit, LLC has adopted the following Drug Testing Policy to ensure the validity of the results achieved in competition. -

Disposition of T Oxic Drugs and Chemicals

Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, Eleventh Edition Eleventh Edition in Man and Chemicals Drugs Toxic Disposition of The purpose of this work is to present in a single convenient source the current essential information on the disposition of the chemi- cals and drugs most frequently encountered in episodes of human poisoning. The data included relate to the body fluid concentrations of substances in normal or therapeutic situations, concentrations in fluids and tissues in instances of toxicity and the known metabolic fate of these substances in man. Brief mention is made of specific analytical procedures that are applicable to the determination of each substance and its active metabolites in biological specimens. It is expected that such information will be of particular interest and use to toxicologists, pharmacologists, clinical chemists and clinicians who have need either to conduct an analytical search for these materials in specimens of human origin or to interpret 30 Amberwood Parkway analytical data resulting from such a search. Ashland, OH 44805 by Randall C. Baselt, Ph.D. Former Director, Chemical Toxicology Institute Bookmasters Foster City, California HARD BOUND, 7” x 10”, 2500 pp., 2017 ISBN 978-0-692-77499-1 USA Reviewer Comments on the Tenth Edition “...equally useful for clinical scientists and poison information centers and others engaged in practice and research involving drugs.” Y. Caplan, J. Anal. Tox. “...continues to be an invaluable and essential resource for the forensic toxicologist and pathologist.” D. Fuller, SOFT ToxTalk “...has become an essential reference book in many laboratories that deal with clinical or forensic cases of poisoning.” M. -

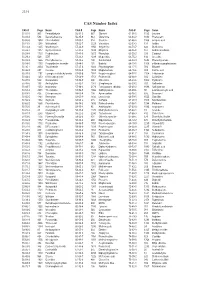

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

LIGANDROL Comprometimento Ósseo

Apresenta ação anabólica com poucos efeitos androgênicos e virilizantes Auxilia no tratamento de condições onde há perda de massa muscular e LIGANDROL comprometimento ósseo Promove a hipertrofia e aumenta a força muscular O QUE É? RA especialmente pelos ligantes exógenos, como os esteróides anabolizantes androgênicos (EAA), pode estar envolvida com o O ligandrol, também conhecido como anabolicum ou LGD- desenvolvimento de patologias na próstata, coração e fígado. Isto 4033, é caracterizado como um modulador seletivo do receptor porque, o receptor RA está expresso em diferentes tecidos, o que de androgênio (SARM) de estrutura não esteroidal que atua de de certa forma limita o uso terapêutico dos EAA em condições forma seletiva sobre os tecidos que expressam os receptores mais específicas como sarcopenia, caquexia associada à doenças androgênicos (RA). Por sua especificidade e alta afinidade ao como câncer, osteoporose e hipogonadismo. RA, tem sido demonstrado que o ligandrol apresenta atividade anabólica no músculo e anti – reabsortiva e anabólica no tecido Com o intuito de contornar possíveis limitações que resultam da ósseo, ao passo que apresenta efeitos androgênicos mínimos ativação global dos RA, os moduladores seletivos de receptores sobre próstata, couro cabeludo e pele. 1 androgênicos, também conhecidos como SARMs, do inglês Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators, tem sido objeto de Os SARMs como o ligandrol e ostarine, têm sido avaliados como estudo uma vez que parecem ativar os RA de maneira específica uma alternativa eficaz e segura para o tratamento de perda e seletiva em determinados tecidos, reduzindo também a de massa muscular associada ao envelhecimento e a outras ocorrência de efeitos colaterais indesejados. -

April 2020 Sanctions List Full

GLOBAL LIST OF INELIGIBLE PERSONS Period of Date of Discipline Date of Ineligibility Lifetime Infraction Name Nationality Role Sex Discipline 2 Sanction Disqualification ADRV Rules ADRV Notes Description Birth 1 Infraction until Ban? Type of results ABAKUMOVA, Maria 15/01/1986 RUS athlete F Javelin Throws 21/08/2008 4 years 17/05/2020 From 21.08.08 to No Doping Presence,Use Dehydrochlormethyltestost In competition test, XXIX Olympic ineligibility 20.08.12 erone games, Beijing, CHN ABDOSH, Ali 25/08/1987 ETH athlete M Long Distance 24/12/2017 4 years 04/02/2022 Since 24-12-2017 No Doping Presence,Use Salbutamol In competition test, 2017 Baoneng (3000m+) ineligibility Guangzhou Huangpu Marathon , Guangzhou, CHN ABDUL SHAHID (NASERA), Haidar 13/01/1981 IRQ athlete M Throws 08/03/2019 4 years 05/05/2023 Since 08.03.19 No Doping Presence,Use Metandienone In competition test, Iraqi ineligibility Championships, Baghdad, IRQ ACHERKI, Mounir 09/02/1981 FRA athlete M 1500m Middle Distance 01/01/2014 4 years 15/04/2021 Since 01-01-2014 No Doping Use,Possessio Use or Attempted Use by an IAAF Rule 32.2(b) Use of a prohibited (800m-1500m) ineligibility n Athlete of a Prohibited substance Substance or a Prohibited IAAF Rule 32.2(f) Possession of a Method, Possession of a prohibited substance Prohibited Substance or a Prohibited Method ADAMCHUK, Mariya 29/05/2000 UKR athlete F Long Jump Jumps 03/06/2018 4 years 16/08/2022 Since 03.06.18 No Doping Presence,Use Trenbolone, DMBA & ICT, Ukrainian club U20 ineligibility Methylhexaneamine Championships', Lutsk, UKR ADEKOYA, Kemi 16/01/1993 BRN athlete F 400m Sprints (400m or 24/08/2018 4 years 25/11/2022 Since 24.08.18 No Doping Presence,Use Stanozolol Out-of-competition test, Jakarta, IDN Hurdles less) ineligibility ADELOYE, Tosin 07/02/1996 NGR athlete F 400m Sprints (400m or 24/07/2015 8 years 23/07/2023 Since 24-07-2015 No Doping Presence,Use Exogenous Steroids In competition test, Warri Relays - less) ineligibility (2nd CAA Super Grand Prix , Warri, NGR ADRV) ADLI SAIFUL, Muh. -

Hsa Updates on Products Found Overseas That Contain Potent Ingredients (November – December 2019)

HSA UPDATES ON PRODUCTS FOUND OVERSEAS THAT CONTAIN POTENT INGREDIENTS (NOVEMBER – DECEMBER 2019) The Health Sciences Authority (HSA) would like to update the public on products that have been found and reported by overseas regulators between November and December 2019 to contain potent ingredients which are not allowed in these products and may cause side effects. This information is provided to increase awareness on safety issues of such products found overseas, which may impact the local population. Please refer to Annex A and Annex B for the list of products and the possible side effects of the potent ingredients. HSA’s Advisory 2 Members of the public are advised to: Consult a doctor if you have consumed any of the products and are feeling unwell. Avoid buying any of the products when abroad. Exercise caution when purchasing health products online or from sources (either local or overseas) which you may not be familiar with, even if well- meaning friends or relatives have recommended them. You cannot be certain where and how these products were made. They may be illegal, counterfeit or substandard, and may contain potent ingredients which can harm your health. If buying health products online, we encourage you to buy them from websites with an established retail presence in Singapore. Be wary of products that promise quick and miraculous results or carry exaggerated claims like “100% safe”, “no side effects” or “scientifically proven”. Consumers should also be cautious of products that produce unexpected quick recovery of medical conditions. Consult your doctor or pharmacist if you need help for the management of your acute and chronic medical symptoms and conditions (e.g. -

Resistance to Second Generation Antiandrogens in Prostate Cancer: Pathways and Mechanisms

Verma et al. Cancer Drug Resist 2020;3:742-61 Cancer DOI: 10.20517/cdr.2020.45 Drug Resistance Review Open Access Resistance to second generation antiandrogens in prostate cancer: pathways and mechanisms Shiv Verma1,2, Kumari Sunita Prajapati3, Prem Prakash Kushwaha3, Mohd Shuaib3, Atul Kumar Singh3, Shashank Kumar3, Sanjay Gupta1,2,4,5,6 1Department of Urology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA. 2The Urology Institute, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA. 3School of Basic and Applied Sciences, Department of Biochemistry and Microbial Sciences, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda 151001, India. 4Department of Nutrition, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA. 5Divison of General Medical Sciences, Case Comprehensive Cancer Center, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA. 6Department of Urology, Louis Stokes Cleveland Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA. Correspondence to: Prof. Sanjay Gupta, The James and Eilleen Dicke Laboratory, Department of Urology, Case Western Reserve University, 2109 Adelbert Road, Wood Research Tower-RTG01, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA. E-mail: [email protected] How to cite this article: Verma S, Prajapati KS, Kushwaha PP, Shuaib M, Singh AK, Kumar S, Gupta S. Resistance to second generation antiandrogens in prostate cancer: pathways and mechanisms. Cancer Drug Resist 2020;3:742-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cdr.2020.45 Received: 24 Jun 2020 First Decision: 31 Jul 2020 Revised: 3 Aug 2020 Accepted: 6 Aug 2020 Available online: 17 Sep 2020 Academic Editor: Vincent C. O. Njar Copy Editor: Cai-Hong Wang Production Editor: Jing Yu Abstract Androgen deprivation therapy targeting the androgens/androgen receptor (AR) signaling continues to be the mainstay treatment of advanced-stage prostate cancer. -

Banned Substances in Sports Supplements

Banned substances in sports supplements Consumer Information Sheet The Health Protection Service (HPS) is aware that sports supplements labelled as containing banned substances are being sold in the ACT primarily through retail supplement stores. Banned substances include selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs), stenabolic, ibutamoren, cardarine, tadalafil, oxedrine, melatonin, phenibut, clomifene, l-dopa and DHEA. Most of these substances are associated with significant health and safety concerns and their long-term effects on the human body are unknown. Some substances are prescription medicines that without appropriate medical management and monitoring, pose significant risks to the individuals who take them. Some substances are prohibited substances that are associated with high risk of harm to individuals who take them and have no therapeutic purpose. This information sheet provides further details on these substances. If you are taking a supplement which is labelled as containing a banned substance and that has not been prescribed by your doctor, you should stop taking it immediately and report the name of the product and place of purchase to the Pharmaceutical Services Section of the HPS on (02) 6205 0998. If you have concerns about your health, please see your General Practitioner. Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs) SARMs are a group of compounds which act in a similar way to anabolic steroids and cause tissue (bone and muscle) growth. Unlike anabolic steroids, SARMs are less likely to cause unfavourable side effects such as the development of male gender characteristics in females, and the development of baldness, breast tissue and testicular shrinkage in males. SARMs are associated with serious safety concerns including liver toxicity and the potential to increase the risk of heart attack and stroke.1 The long-term effects of SARMs on the human body are unknown. -

Student-Athlete Expectations and Responsibilities

2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Mission and Philosophy Virginia Wesleyan University Mission NCAA Philosophy VWU Intercollegiate Athletics Mission Athletics Staff Directory Academic Support Program, Requirements and Eligibility Scheduling Guidelines for Academics and Athletics Conflicts Academic Support Services Faculty Team Advisors Program Student-Athlete Academic Requirements Athletic Eligibility Student Athlete Expectations and Responsibilities Campus Citizenship Hosting Prospective Students Social Media and Hazing Celebrating Our Successes Student Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC) President’s List and Dean’s List Award Recognition Events Chi Alpha Sigma Honor Society Athletic Training/Sports Medicine Drug and Alcohol Policies Alcohol Policy Statement Drug Policy Statement 2021-22 NCAA Banned Substances 3 MISSION AND PHILOSOPHY Virginia Wesleyan University Mission An inclusive community dedicated to scholarship and service grounded in the liberal arts and sciences, Virginia Wesleyan University inspires students to build meaningful lives through engagement in Coastal Virginia's dynamic metropolitan region, the nation, and the world. NCAA Philosophy Colleges and universities in Division III place the highest priority on the overall quality of the educational experience and on the successful completion of all students’ academic programs. They seek to establish and maintain an environment in which a student athlete’s athletics activities are conducted as an integral part of the student-athlete’s educational experience, and an environment that values -

2019-20 NCAA Banned Substances It Is the Student-Athlete's

2019-20 NCAA Banned Substances It is the student-athlete’s responsibility to check with the appropriate or designated athletics staff before using any substance. The NCAA bans the following drug classes. a. Stimulants b. Anabolic agents c. Alcohol and beta blockers (banned for rifle only) d. Diuretics and masking agents e. Narcotics f. Cannabinoids g. Peptide hormones, growth factors, related substances and mimetics h. Hormone and metabolic modulators (anti-estrogens) i. Beta-2 agonists Note: Any substance chemically/pharmacologically related to all classes listed above and with no current approval by any governmental regulatory health authority for human therapeutic use (e.g., drugs under pre-clinical or clinical development or discontinued, designer drugs, substances approved only for veterinary use) is also banned. The institution and the student-athlete shall be held accountable for all drugs within the banned-drug class regardless of whether they have been specifically identified. Examples of substances under each class can be found at www.ncaa.org/drugtesting. There is no complete list of banned substances. Substances and Methods Subject to Restrictions: • Blood and gene doping. • Local anesthetics (permitted under some conditions). • Manipulation of urine samples. • Beta-2 agonists (permitted only by inhalation with prescription). • Tampering of urine samples. NCAA Nutritional/Dietary Supplements: Warning: Before consuming any nutritional/dietary supplement product, review the product and its label with your athletics department staff! • Nutritional/Dietary supplements, including vitamins and minerals, are not well regulated and may cause a positive drug test. • Student-athletes have tested positive and lost their eligibility using nutritional/dietary supplements. • Many nutritional/dietary supplements are contaminated with banned substances not listed on the label. -

Veterinary Technical Bulletin April 20, 2020

1 Veterinary Technical Bulletin April 20, 2020 1. Medroxyprogesterone (MPA) The administration of medroxyprogesterone (once available as Depo-Provera) to horses has been associated with adverse events including anaphylactic reactions and sudden death. The United States Equestrian Federation established MPA as a prohibited substance as of December 1, 2019 (https://www.usef.org/media/press-releases/usef-board-of-directors- prohibits-use-of ). In 2019, the American Association of Equine Practitioners issued the following statement in regarding the use of MPA in competition horses: Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) is a synthetic progestin hormone administered to mares off-label in an attempt to suppress behavioral estrus. However, a controlled research study found that MPA was not effective at suppression of behavioral estrus. (1) Many veterinarians believe MPA modifies behavior by producing a calming effect in the horse and does not have a therapeutic benefit that goes beyond this behavior modification. Therefore, the AAEP recommends that MPA should not be administered to horses in competition. Gee EK, C DeLuca, JL Stylski, PM McCue. Efficacy of medroxyprogesterone acetate in suppression of estrus in cycling mares. J Equine Vet Sci 2009;29:140-145. In consideration of the following: 1) Altrenogest (Regumate) has FDA-approval for use in the suppression of estrus and its use is permitted in fillies and mares in training and racing, 2) there is no evidence for efficacy of MPA in suppressing estrus, 3) there is no indication for the administration of MPA as a therapeutic medication, 4) there is evidence for risk to horses in the administration of MPA. The RMTC recommends that MPA not be used.