Biodiversity Influences Plant Productivity Through Niche–Efficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coptis Trifolia Conservation Assessment

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT for Coptis trifolia (L.) Salisb. Originally issued as Management Recommendations December 1998 Marty Stein Reconfigured-January 2005 Tracy L. Fuentes USDA Forest Service Region 6 and USDI Bureau of Land Management, Oregon and Washington CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT FOR COPTIS TRIFOLIA Table of Contents Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 2 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 2 Summary........................................................................................................................................ 4 I. NATURAL HISTORY............................................................................................................. 6 A. Taxonomy and Nomenclature.......................................................................................... 6 B. Species Description ........................................................................................................... 6 1. Morphology ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Reproductive Biology.................................................................................................... 7 3. Ecological Roles ............................................................................................................. 7 C. Range and Sites -

Economic and Ethnic Uses of Bryophytes

Economic and Ethnic Uses of Bryophytes Janice M. Glime Introduction Several attempts have been made to persuade geologists to use bryophytes for mineral prospecting. A general lack of commercial value, small size, and R. R. Brooks (1972) recommended bryophytes as guides inconspicuous place in the ecosystem have made the to mineralization, and D. C. Smith (1976) subsequently bryophytes appear to be of no use to most people. found good correlation between metal distribution in However, Stone Age people living in what is now mosses and that of stream sediments. Smith felt that Germany once collected the moss Neckera crispa bryophytes could solve three difficulties that are often (G. Grosse-Brauckmann 1979). Other scattered bits of associated with stream sediment sampling: shortage of evidence suggest a variety of uses by various cultures sediments, shortage of water for wet sieving, and shortage around the world (J. M. Glime and D. Saxena 1991). of time for adequate sampling of areas with difficult Now, contemporary plant scientists are considering access. By using bryophytes as mineral concentrators, bryophytes as sources of genes for modifying crop plants samples from numerous small streams in an area could to withstand the physiological stresses of the modern be pooled to provide sufficient material for analysis. world. This is ironic since numerous secondary compounds Subsequently, H. T. Shacklette (1984) suggested using make bryophytes unpalatable to most discriminating tastes, bryophytes for aquatic prospecting. With the exception and their nutritional value is questionable. of copper mosses (K. G. Limpricht [1885–]1890–1903, vol. 3), there is little evidence of there being good species to serve as indicators for specific minerals. -

Vermont Natural Community Types

Synonymy of Vermont Natural Community Types with National Vegetation Classification Associations Eric Sorenson and Bob Zaino Natural Heritage Inventory Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department October 17, 2019 Vermont Natural Community Type Patch State National and International Vegetation Classification. NatureServe. 2019. Size Rank NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Spruce-Fir-Northern Hardwood Forest Formation Subalpine Krummholz S S1 Picea mariana - Abies balsamea / Sibbaldiopsis tridentata Shrubland (CEGL006038); (Picea mariana, Abies balsamea) / Kalmia angustifolia - Ledum groenlandicum Dwarf-shrubland Montane Spruce-Fir Forest L-M S3 Picea rubens - Abies balsamea - Sorbus americana Forest (CEGL006128) Variant: Montane Fir Forest L-M S3 Abies balsamea - (Betula papyrifera var. cordifolia) Forest (CEGL006112) Variant: Montane Spruce Forest Lowland Spruce-Fir Forest L-M S3 Picea mariana - Picea rubens / Pleurozium schreberi Forest (CEGL006361) Variant: Well-Drained Lowland Spruce- L S2 Picea rubens - Abies balsamea - Betula papyrifera Forest (CEGL006273); Fir Forest Picea mariana - Picea rubens / Rhododendron canadense / Cladina spp. Woodland (CEGL006421) Montane Yellow Birch-Red Spruce Forest M S3 Betula alleghaniensis - Picea rubens / Dryopteris campyloptera Forest (CEGL006267) Variant: Montane Yellow Birch-Sugar L S3 Maple-Red Spruce Forest Red Spruce-Northern Hardwood Forest M S5 Betula alleghaniensis - Picea rubens / Dryopteris campyloptera Forest (CEGL006267) Red Spruce-Heath -

Appendix 2: Plant Lists

Appendix 2: Plant Lists Master List and Section Lists Mahlon Dickerson Reservation Botanical Survey and Stewardship Assessment Wild Ridge Plants, LLC 2015 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Acalypha rhomboidea Native 1 Forb 9 Acer palmatum Invasive 0 Tree 1 Acer pensylvanicum Native 7 Tree 2 Acer platanoides Invasive 0 Tree 4 Acer rubrum Native 3 Tree 27 Acer saccharum Native 5 Tree 24 Achillea millefolium Native 0 Forb 18 Acorus calamus Alien 0 Forb 1 Actaea pachypoda Native 5 Forb 10 Adiantum pedatum Native 7 Fern 7 Ageratina altissima v. altissima Native 3 Forb 23 Agrimonia gryposepala Native 4 Forb 4 Agrostis canina Alien 0 Graminoid 2 Agrostis gigantea Alien 0 Graminoid 8 Agrostis hyemalis Native 2 Graminoid 3 Agrostis perennans Native 5 Graminoid 18 Agrostis stolonifera Invasive 0 Graminoid 3 Ailanthus altissima Invasive 0 Tree 8 Ajuga reptans Invasive 0 Forb 3 Alisma subcordatum Native 3 Forb 3 Alliaria petiolata Invasive 0 Forb 17 Allium tricoccum Native 8 Forb 3 Allium vineale Alien 0 Forb 2 Alnus incana ssp rugosa Native 6 Shrub 5 Alnus serrulata Native 4 Shrub 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia Native 0 Forb 14 Amelanchier arborea Native 7 Tree 26 Amphicarpaea bracteata Native 4 Vine, herbaceous 18 2015 MASTER PLANT LIST MAHLON DICKERSON RESERVATION SCIENTIFIC NAME NATIVENESS S-RANK CC PLANT HABIT # OF SECTIONS Anagallis arvensis Alien 0 Forb 4 Anaphalis margaritacea Native 2 Forb 3 Andropogon gerardii Native 4 Graminoid 1 Andropogon virginicus Native 2 Graminoid 1 Anemone americana Native 9 Forb 6 Anemone quinquefolia Native 7 Forb 13 Anemone virginiana Native 4 Forb 5 Antennaria neglecta Native 2 Forb 2 Antennaria neodioica ssp. -

Summary Data

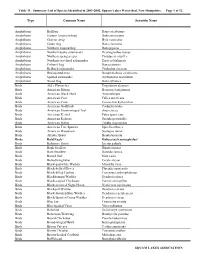

Table 11. Summary List of Species Identified in 2001-2002, Squam Lakes Watershed, New Hampshire. Page 1 of 12 Type Common Name Scientific Name Amphibians Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana Amphibians Eastern American toad Bufo americanus Amphibians Gray treefrog Hyla versicolor Amphibians Green frog Rana clamitans Amphibians Northern leopard frog Rana pipiens Amphibians Northern dusky salamander Desmognathus fuscus Amphibians Northern spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer Amphibians Northern two-lined salamander Eurycea bislineata Amphibians Pickerel frog Rana palustris Amphibians Redback salamander Plethodon cinereus Amphibians Red-spotted newt Notophthalmus viridescens Amphibians Spotted salamander Ambystoma maculatum Amphibians Wood frog Rana sylvatica Birds Alder Flycatcher Empidonax alnorum Birds American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Birds American Black Duck Anas rubripes Birds American Coot Fulica americana Birds American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Birds American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis Birds American Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Birds American Kestrel Falco sparverius Birds American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Birds American Robin Turdus migratorius Birds American Tree Sparrow Spizella arborea Birds American Woodcock Scolopax minor Birds Atlantic Brant Branta bernicla Birds Bald Eagle* Haliaeetus leucocephalus* Birds Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula Birds Bank Swallow Riparia riparia Birds Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica Birds Barred Owl Strix varia Birds Belted Kingfisher Ceryle alcyon Birds Black-and-white Warbler Mniotilta varia Birds -

Species List For: Labarque Creek CA 750 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location 4/19/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey

Species List for: LaBarque Creek CA 750 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location 4/19/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey 5/15/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey 5/16/2006 Nels Holmberg, George Yatskievych, and Rex Plant Survey Hill 5/22/2006 Nels Holmberg and WGNSS Botany Group Plant Survey 5/6/2006 Nels Holmberg Plant Survey Multiple Visits Nels Holmberg, John Atwood and Others LaBarque Creek Watershed - Bryophytes Bryophte List compiled by Nels Holmberg Multiple Visits Nels Holmberg and Many WGNSS and MONPS LaBarque Creek Watershed - Vascular Plants visits from 2005 to 2016 Vascular Plant List compiled by Nels Holmberg Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha monococca (A. gracilescens var. monococca) one-seeded mercury Euphorbiaceae 3 5 Acalypha rhomboidea rhombic copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 1 3 Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer negundo var. undetermined box elder Sapindaceae 1 0 Acer rubrum var. undetermined red maple Sapindaceae 5 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple Sapindaceae 2 -3 Acer saccharum var. undetermined sugar maple Sapindaceae 5 3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Ranunculaceae 8 5 Adiantum pedatum var. pedatum northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Fern/Ally 6 1 Agalinis gattingeri (Gerardia) rough-stemmed gerardia Orobanchaceae 7 5 Agalinis tenuifolia (Gerardia, A. tenuifolia var. common gerardia Orobanchaceae 4 -3 macrophylla) Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia parviflora swamp agrimony Rosaceae 5 -1 Agrimonia pubescens downy agrimony Rosaceae 4 5 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Agrostis elliottiana awned bent grass Poaceae/Aveneae 3 5 * Agrostis gigantea redtop Poaceae/Aveneae 0 -3 Agrostis perennans upland bent Poaceae/Aveneae 3 1 Allium canadense var. -

<I>Sphagnum</I> Peat Mosses

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12547 Evolution of niche preference in Sphagnum peat mosses Matthew G. Johnson,1,2,3 Gustaf Granath,4,5,6 Teemu Tahvanainen, 7 Remy Pouliot,8 Hans K. Stenøien,9 Line Rochefort,8 Hakan˚ Rydin,4 and A. Jonathan Shaw1 1Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 2Current Address: Chicago Botanic Garden, 1000 Lake Cook Road Glencoe, Illinois 60022 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Plant Ecology and Evolution, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyvagen¨ 18D, SE-752 36, Uppsala, Sweden 5School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 6Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-750 07, Uppsala, Sweden 7Department of Biology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, 80101, Joensuu, Finland 8Department of Plant Sciences and Northern Research Center (CEN), Laval University Quebec, Canada 9Department of Natural History, Norwegian University of Science and Technology University Museum, Trondheim, Norway Received March 26, 2014 Accepted September 23, 2014 Peat mosses (Sphagnum)areecosystemengineers—speciesinborealpeatlandssimultaneouslycreateandinhabitnarrowhabitat preferences along two microhabitat gradients: an ionic gradient and a hydrological hummock–hollow gradient. In this article, we demonstrate the connections between microhabitat preference and phylogeny in Sphagnum.Usingadatasetof39speciesof Sphagnum,withan18-locusDNAalignmentandanecologicaldatasetencompassingthreelargepublishedstudies,wetested -

Liverworts Mosses

LIVERWORTS LIVERWORTS MOSSES Heller’s Notchwort (Anastrophyllum hellerianum) Hatcher’s Paw-wort (Barbilophozia hatcheri) Key features for identifying Key features for identifying liverworts Mosses Growth form. There are two sorts of liverworts; leafy Growth form. Leaving aside the very distinctive bog- liverworts have a stem and leaves and resemble a mosses (Sphagnum), mosses can be split into two moss, whereas thallose or thalloid liverworts have a groups, acrocarpous and pleurocarpous. There is a simple strap of tissue with no stem or leaves. Leafy technical difference between these two forms but in liverworts can form erect cushions and turfs while some practical terms, acrocarps usually have erect stems are creeping and closely apressed to rock or tree. The and grow in cushions or turfs while pleurocarps tend size of the plant is also important; a number of oceanic Michael Lüth to grow with main stems parallel to the ground (or rock Leafy liverwort NS; size: very small and forming thin patches Leafy liverwort; size: small to medium-sized forming tight liverworts are very, very small. Above - Left: acrocarpous Scott’s Fork moss (Dicranum Above - Left: a thallose liverwort, Overleaf Pellia (Pellia or tree trunk) and form wefts. The often dense growth of upright stems; colour: yellow or yellow green with shoot patches of erect stems; colour: mid or yellow green, often with Leaf shape. This is all-important in leafy liverworts and scottianum) ; right: pleurocarpous Larger Mouse-tail epiphylla) with fruits; right: a leafy liverwort with round form of acrocarps means that their sparse branches tips red with gemmae; leaves: tiny with two lobes but hardly some shoot tips red with gemmae; leaves: rounded-rectangular leaves, Autumn Flapwort (Jamesoniella autumnalis). -

Dimensions of Biodiversity

Dimensions of Biodiversity NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION CO-FUNDED BY 2010–2015 PROJECTS Introduction 4 Project Abstracts 2015 8 Project Updates 2014 30 Project Updates 2013 42 Project Updates 2012 56 Project Updates 2011 72 Project Updates 2010 88 FRONT COVER IMAGES A B f g h i k j C l m o n q p r D E IMAGE CREDIT THIS PAGE FRONT COVER a MBARI & d Steven Haddock f Steven Haddock k Steven Haddock o Carolyn Wessinger Peter Girguis e Carolyn g Erin Tripp l Lauren Schiebelhut p Steven Litaker b James Lendemer Wessinger h Marty Condon m Lawrence Smart q Sahand Pirbadian & c Matthew L. Lewis i Marty Condon n Verity Salmon Moh El-Naggar j Niklaus Grünwald r Marty Condon FIELD SITES Argentina France Singapore Australia French Guiana South Africa Bahamas French Polynesia Suriname Belize Germany Spain Bermuda Iceland Sweden Bolivia Japan Switzerland Brazil Madagascar Tahiti Canada Malaysia Taiwan China Mexico Thailand Colombia Norway Trinidad Costa Rica Palau United States Czech Republic Panama United Kingdom Dominican Peru Venezuela Republic Philippines Labrador Sea Ecuador Poland North Atlantic Finland Puerto Rico Ocean Russia North Pacific Ocean Saudi Arabia COLLABORATORS Argentina Finland Palau Australia France Panama Brazil Germany Peru Canada Guam Russia INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS Chile India South Africa China Brazil China Indonesia Sri Lanka (NSFC) (FAPESP) Colombia Japan Sweden Costa Rica Kenya United Denmark Malaysia Kingdom Ecuador Mexico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many NSF staff members, too numerous to We thank Mina Ta and Matthew Pepper for mention individually, assisted in the development their graphic design contribution to the abstract and implementation of the Dimensions of booklet. -

Patterns of Bryophyte Succession in a 160-Year Chronosequence in Deciduous and Coniferous Forests of Boreal Alaska Mélanie Jean, Heather D

1021 ARTICLE Patterns of bryophyte succession in a 160-year chronosequence in deciduous and coniferous forests of boreal Alaska Mélanie Jean, Heather D. Alexander, Michelle C. Mack, and Jill F. Johnstone Abstract: Bryophytes are dominant components of boreal forest understories and play a large role in regulating soil microcli- mate and nutrient cycling. Therefore, shifts in bryophyte communities have the potential to affect boreal forests’ ecosystem processes. We investigated how bryophyte communities varied in 83 forest stands in interior Alaska that ranged in age (since fire) from 8 to 163 years and had canopies dominated by deciduous broadleaf (Populus tremuloides Michx. or Betula neoalaskana Sarg.) or coniferous trees (Picea mariana Mill B.S.P.). In each stand, we measured bryophyte community composition, along with environ- mental variables (e.g., organic layer depth, leaf litter cover, moisture). Bryophyte communities were initially similar in deciduous vs. coniferous forests but diverged in older stands in association with changes in organic layer depth and leaf litter cover. Our data suggest two tipping points in bryophyte succession: one at the disappearance of early colonizing taxa 20 years after fire and another at 40 years after fire, which corresponds to canopy closure and differential leaf litter inputs in mature deciduous and coniferous canopies. Our results enhance understanding of the processes that shape compositional patterns and ecosystem services of bryophytes in relation to stand age, canopy composition, and changing disturbances such as fire that may trigger changes in canopy composition. Key words: boreal forest, succession, moss, chronosequence, leaf litter, canopy effects, fire, bryophyte. Résumé : Les bryophytes sont des éléments dominants du sous-bois de la forêt boréale et jouent un grand rôle dans la régulation du recyclage des nutriments et du microclimat dans le sol. -

Effects of Forest Fires

Ecological Effects of Forest Fires s 21 .A72 no.1133 letin No. 1133 MARC: 1956 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout the course of the investigations reported here, R. R. Robinson, Area Forester, Bureau of Land Management, U. S. Department of the Interior, was very cooperative. He and his staff assisted greatly in the successful completion of the studies, Officials of the Fish and Wildlife Service, U. S. Department of the Interior, also were very helpful. The University of Alaska generously furnished office space and living quarters during the time the author was completing the report. Various specialists identified . the plants collected in Alaska. Special recognition is given to their assistance, as follows: William A. Dayton, U. S. Forest Service-in charge of identification of the higher plants; Elbert L. Little-trees; Doris W. Hayd-most of the herbaceous plants except grasses; Carleton R. Ball (retired), U. S. Department of Agriculture-willows; Jason R. Swallen, Head Curator, U. S. National Herbarium-grasses; William C. Steere, Professor of. Botany, Stanford University-bryophytes; Alexander W. Evans, Emeritus Professor of Botany, Yale Uni versity-Cladoniae; John W. Thomson, Jr., Associate Professor of Bot~ny, University of Wisconsin-various groups of lichens; and I. MacKenzie Lamb, National Museum ~f Canada-Stereocaula. I CONTENTS Page Page Introduction____________________ 1 Effect of fire on soils-Continued Interior of Alaska_______________ 3 Sqil productivity______________ 78 Geography___________________ 3 Effect -

(Black Spruce)- Pleurozium Forests of South-Eastern Labrador, Canada Author(S): David R

Vegetation Development Following Fire in Picea Mariana (Black Spruce)- Pleurozium Forests of South-Eastern Labrador, Canada Author(s): David R. Foster Source: Journal of Ecology, Vol. 73, No. 2 (Jul., 1985), pp. 517-534 Published by: British Ecological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2260491 . Accessed: 05/08/2011 12:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. British Ecological Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Ecology. http://www.jstor.org Journal of Ecology (1985), 73, 5 17-534 VEGETATION DEVELOPMENT FOLLOWING FIRE IN PICEA MARIANA (BLACK SPRUCE)-PLEUR OZIUM FORESTS OF SOUTH-EASTERN LABRADOR, CANADA DAVID R. FOSTER Harvard University,Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts 01366, U.S.A. SUMMARY (1) The pattern of post-fire vegetation development in Picea mariana (black spruce)- Pleurozium forests in south-eastern Labrador,Canada, is evaluated using palaeoecological methods and vegetation analysis of extant stands. (2) Macrofossil analysis of mor humus profiles in mature stands yields the following stratigraphy: mineral soil-charcoal-Polytrichum juniperinum-Cladonia lichens- Pleurozium schreberi-feather mosses and Sphagnum girgensohnii. The stratigraphic record of the post-fire dynamics of the vegetation at individual sites strengthens the conclusions obtained from the detailed analysis of a chronosequence of stands.