Assisting Media Democratization After Low-Intensity Conflict: the Case of Macedonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macedonia Competitiveness Activity Quarterly Report April 2006 – June 2006

Macedonia Competitiveness Activity Quarterly Report April 2006 – June 2006 ul. Bukureska 133b Skopje, Macedonia Tel: (389 2) 309-1711; Fax: (389 2) 307-9158 MACEDONIA COMPETITIVENESS ACTIVITY Quarterly Report: April – June 2006 Executive Summary NECC: The National Entrepreneurship & Competitiveness Council celebrated its three- year anniversary. The role of the Council was formally recognized by the government as a forum and means for dialogue between the public and the private sectors. Macedonia received higher credit rating from Fitch Credit of London and was described as a safer investment destination. PED: By conducting a one-month PR road show around the country MCA’s Public Education Department (PED) reinforced cluster messages and widely publicized the results achieved. Special printed materials on each cluster and the NECC, featuring the MCA final stage results, have supported the campaign. An event to celebrate the project’s outstanding results crowned the forward-set MCA PR strategy. PED staff managed to maintain good communication with the media/public despite the governmental elections' black out period. Lamb and Cheese: LTM (Lamb to Market) set up a functional sales structure to take advantage of opportunities to place Macedonian lamb in the Greek market year round. The LTM team plans to host a visit of the appointed sales agent and a potential client in order to demonstrate the capabilities of Macedonian lamb producers to satisfy the needs of Greek lamb buyers. Tourism: Members of the Tourism Cluster and the Tikves Wine Road Foundation worked together to initiate the development of wine tourism in the Tikves Region. With assistance from MCA Tourism Consultant, Susan Snelson, the group built a solid base for future development of tourism in the Tikves region. -

ANNUAL Report : 2005 / Foundation Open Society Institute - Macedonia ; (Editor Marijana Ivanova)

Publisher: Foundation Open Society Institute - Macedonia Bul. Jane Sandanski , POB 378 000 Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Tel.: ++3892 2444-488 Fax: ++3892 2444-499 E-mail: [email protected] www.soros.org.mk For the publisher: Vladimir Milcin Editor: Marijana Ivanova Proof Reading: Abakus, Skopje Design, Layout & Print: Koma lab., Skopje Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, 2006 Print run: 500 ISBN 9989-834-92-X CIP - Katalogizacija vo publikacija Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka “Sv. Kliment Ohridski”, Skopje 061.27(497.7)”2005”(047) ANNUAL report : 2005 / Foundation Open Society Institute - Macedonia ; (editor Marijana Ivanova). - Skopje : Foundation Open Society Institute Macedonia, 2006. - 179 str. ; 19 sm Sodr`i i : Annexes ISBN 9989-834-92-X a) Fondacija Institut otvoreno op{testvo Makedonija - 2005 - Izve{tai COBISS.MK-ID 66050058 Institute - Macedonia OpenSociety Foundation Annual Report 2 0 0 5 3 Contents 5 Foreword 7 Contacts and Organizational Set-up 9 Partners and Donors 13 106 Important Events Programs 16 Roma (Inter-program Initiatives) 18 Education Program 26 108 Financial Report Youth Program 34 Information Program 38 132 Annexes Public Health Program 46 133 Annex - Grant Lists Economic Reform Program 52 157 Annex 2 - Consolidated Arts and Culture Program 58 Financial Statements Media Program 64 Public Administration Reform Program 70 Law Program 78 Civil Society Program 84 East-East Program and 96 Other Regional Projects 6 FOREWORD 7 FOSIM IN 2005: LOBBYING, ADVOCATING AND INITIATING CHANGES The year subject of this report is a historic one for the Re- public of Macedonia. It was the year in which the Republic of Macedonia acquired the status of candidate-country for EU membership. -

Kako Da Komunicirate So Mediumite.Pdf

Kako da KOMUNICIRATE SO MEDIUMITE Makedonski institut za mediumi za institut Makedonski SODR@INA I DA ZAPO^NEME 6 [1] Mediumska strategija 7 [2] Klu~ni lu|e i resursi 9 [3] Razvivawe na porakata 13 Studija na slu~aj: Vklu~uvawe na zaednicata 19 II ALATKI 24 [1] Soop{tenie za pe~at 25 [2] Konferencija za pe~at 30 [3] Brifing za novinari 35 [4] Poseta za novinari 37 Studija na slu~aj: Vidlivost na va{ata rabota 40 [5] Intervju 43 [6] Ubeduva~ko pismo 46 [7] Mediumski nastani 47 [8] Drugi formi (Bilten, pismo do urednikot) 51 III KOMUNIKACIJA VO USLOVI NA KRIZA 55 [1] Komunikacija vo uslovi na kriza 56 Studija na slu~aj: Komunicirawe za vreme na kriza 58 IV MONITORING I EVALUACIJA 61 [1] Monitoring i evaluacija 62 V DODATOCI: 66 [1] Kodeks na novinarite na Makedonija 67 [2] Poimnik 71 [3] Kontakt informacii za glavnite mediumi vo Makedonija 75 Priznanija i Bibliografija 79 Izdava~: Makedonski institut za mediumi Porta Buwakovec A2/1, 1000 Skopje - Republika Makedonija tel. +389 2 329 8466 faks. +389 2 329 0483 [email protected] www.mim.org.mk Prira~nikot go podgotvija: Marina Tuneva -Jovanovska i Jasmina Mironski Urednik: Sally Broughton Ureduva~ki odbor: • Frances Abouzeid • Biljana Bosiqanova • Vawa Mirkovski • Christa A. Skerry • @aneta Trajkoska Prevod od angliski: Zoran Poposki Lektura i korektura: Hatka Smailovi} Grafi~ki dizajn i pe~atewe: KOMA lab. CIP - Katalogizacija vo publikacija Narodna i univerzitetska biblioteka Sv. Kliment Ohridski, Skopje 316.776(035) TUNEVA-Jovanovska, Marina Kako da komunicirate so mediumite?/ (prira~nikot go podgotvija Marina Tuneva-Jovanovska i Jasmina Mironski; urednik Sally Broughton; prevod od angliski Zoran Poposki). -

Summary of the 9Th Session

Summary of the 9th session SKOPJE, 18 February 2014 – The Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services adopted the Draft – Report on the performance of the Broadcasting Council of the Republic of Macedonia for the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2013, the Draft – Form on data on the ownership structure, editors and economic operation of the broadcaster (Form CSE/1 , the Draft – Application Form for registration in the registry of providers of audiovisual media services on demand and the Draft-Registry of providers of audiovisual media services on demand. The Agency adopted the Proposal for initiating proceedings to revoke the broadcasting license to the trade broadcasting company TV ART Kanal LLC Struga. The Agency adopted the Information on the implemented control supervision in terms of compliance with the obligation to broadcast music. The supervision was implemented on the programmes of MRT1, MRT2, Kanal 5 TV, Sitel TV, Telma TV , Alsat M TV and Alfa TV in the period from 10 to 16 February 2014 and it was established that all media broadcasted even a larger volume of vocal and vocal and instrumental music in Macedonian language or the languages of the ethnic communities than the legal minimum. The Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services decided to issue the following certificates for the registered programme packages: -to TCB – cable network operator KTV PESNA Makedonski Brod, a Certificate no.3, whereby the registered programme package, as a whole, is supplemented with the following television programme services: Alfa TV, Nasa TV, Sport Klub 1 , Sport Klub 2 , Sport Klub 3, Golf Klub, Fishing and Hunting, Ultra, Cinemania, MINI Ultra, IQS Live, Planeta, HRT 1 , RTS Sat and RTCG; – to TCB – cable network operator – KABEL- L- NET, a Certificate no. -

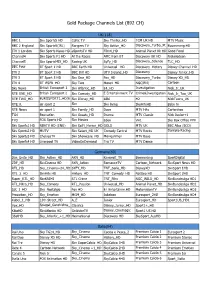

Channel Listล่าสุด2.Xlsx

Gold Package Channels List (892 CH) UK(118) BBC 1 Skv Sports5 HD Celtic TV Sky Thriller_HD TCM UK HD MTV Music BBC 2 England Skv Sports5(IRL) Rangers TV Sky Action_HD Discovery_Turbo_Xt Boomerang HD ITV 1 London Skv Sports News HD eSportsTV HD Film4_HD Animal Planet Uk HD Good Food Channel4 Skv Sports F1 HD At the Races AMC from BT Discovery UK HD Nickelodeon Channel5 Skv SportsMIX_HD Racing UK SyFy_HD Discovery_Science TLC_HD BBC Four BT Sport 1 HD BBC Earth HD Universal _HD Discovery_History Disney Channel_HD ITV 2 BT Sport 2 HD BBC Brit HD UTV Ireland_HD Discovery Disney Junior_HD ITV 3 BT Sport 3 HD Skv One_HD Fox_HD Discovery_Turbo Disney XD_HD ITV 4 BT_ESPN_HD Sky Two More4_HD NGC(EN) Cartoon Sky News British Eurosport 1 Skv Atlantic_HD E4_HD Investigation Nick_Jr_UK RTE ONE_HD British Eurosport 2 Skv Comedy_HD E Entertainment TV Crime&Investigation Nick_Jr_Too_UK RTE TWO_HD EUROSPORT1_HD(E Skv Disney_HD Alibi H2 NickToons_UK RTE jr. eir sport 2 Skv Skv living SkyArtsHD Baby tv RTE News eir sport 1 Skv Family_HD Dave MTV Hits Cartonitoo TG4 Boxnation Skv Greats_HD Drama MTV Classic Nick Junior+1 TV3 FOX Sports HD Skv Movies Eden VH1 Sky Box Office PPV Skv Sports1 HD NBATV HD (ENG) Skv SciFi_Horror_HD GOLD MTV UK BBC Alba (SCO) Skv Sports2 HD MUTV Skv Select_HD UK Comedy Central MTV Rocks Dantoto Racing Skv Sports3 HD ChelseaTV Skv Showcase_HD Movies4men MTV Base Skv Sports4 HD Liverpool TV VideoOnDemand Tru TV MTV Dance Germany(69) Das_Erste_HD Sky_Action_HD AXN_HD Kinowelt_TV Boomerang SportDigital ZDF_HD SkvCinema HD AXN_Action -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

Korica Angl PRINT

“The European Union is made up of 27 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintain- ing cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. The European Union is committed to sharing its achievements and its values with countries and peoples beyond its borders”. The European Commission is the EU’s executive body. ALTYO - Advocacy and Lobbying Training for Youth Organizations is a project imple- mented by Triagolnik with the partner organizations Forum MNE (Montenegro), PRONI Brcko (Bosnia and Herzegovina) and ERYICA (Luxemburg) to: -empower youth CSOs in F.Y.R. of Macedonia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina to effectively influence decision-making processes at national and regional level; -establish cross-cutting policies that will ease the access to the labor market of vulnerable groups of youth. This project is funded A project implemented by by the European Union Center for non-formal education The project is approved by the European Commission in the frame of the IPA 2009 – Triagolnik and partners: Civil Society Facility – Regional Programmes, under the "Support to Partnership Actions to Minorities/Vulnerable Groups Organisations.” How to plan and run advocacy and lobbying campaing Toolkit for civil society organizations Regional project: ALTYO - Advocacy and Lobbying Training for Youth Organizations, implemented by Triagolnik (F.Y.R of Macedonia) with the partner organizations Forum MNE (Montenegro), PRONI Brcko (Bosnia and Herzegovina), and ERYICA (Luxemburg) "This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. -

ME DI JI U VIŠEJE ZIČNIM DRUŠTVI MA Slo Bo Da I Od Go Vornost

ME DI JI U VIŠEJE ZIÈNIM DRUŠTVI MA Slo bo da i od go vornost OEBS-ov Predstav nik za slo bo du me di ja ME DI JI U VIŠEJE ZIÈNIM DRUŠTVI MA Slo bo da i od go vor nost Pri re di la Ana Karlsrajter Prevod: Freimut Duve Milo Dor Tanja Popoviæ Romain Kohn Natalia Angheli Nena Skopljanac Roger Mur Andrea Ochsner Beè, 2003. Izda vaè se za hva lju je Vla di Sa ve zne Repu bli ke Ne maèke na fi nan sij skoj podršci © 2003 Or ga ni za ci ja za evrop sku be zbe dnost i sa ra dnju (OS CE) Kan ce la ri ja Pred stav ni ka za slobo du me di ja Kärtner Ring 5-7, Top 14, 2. DG, A-1010 Vi en na Telefon: +43-1 512 21 450 Telefaks: +43-1 512 21 459 E-ma il: pm-fom@os ce.org Izvešta ji pred stav lja ju iskljuèivo gle dišta samih auto ra i ne od go va ra ju ne op ho dno zva niènim sta vo vi ma OS CE Pred stav ni ka za slo bo du me di ja Sadržaj Fraj mut Du ve Pred go vor.....................7 Mi lo Dor Po zdrav ni go vor.................15 Ta nja Po po viæ Bivša Ju go slo ven ska Repu bli ka Ma ke do ni ja....21 Pre po ru ke za Bivšu Ju go slo ven sku Repu bli ku Ma ke do niju....................45 Ro men Kon Luk sem burg ...................47 Pre po ru ke za Luk semburg ............66 Na ta li ja An ge li Mol da vi ja.....................69 Pre po ru ke za Mol da viju.............91 Ni na Sko plja nac Srbija (Serbija i Crna Go ra)...........93 Preporuke za Srbi ju (Srbiju i Crnu Goru) ....122 Rodžer Blum i Andrea Ošner Švaj car ska....................127 Pre po ru ke za Švaj car sku............156 Pro gram kon fe rencije.................157 Spi sak uè esnika ...................160 Autori ........................162 Fraj mut Duve Pred go vor Ova pu bli ka ci ja je re zul tat pro jek ta po kre nu tog u sep tem - bru 2002: Slo bo da i od go vor nost – Me di ji u više jeziènim dru štvi ma. -

Bad Practices, Bad Faith: Soft Censorship in Macedonia

Bad Practices, Bad Faith: Soft Censorship in Macedonia www.wan-ifra.org Bad Practices, Bad Faith: Soft Censorship in Macedonia PUBLISHER: SEEMO EDITOR: XXXPLEASE MAKE THIS A SMALL TABLE Overview of funds spent in public information campaigns WAN-IFRA Oliver Vujovic 2012 - 6,615,609 EUR World Association of Newspapers 2013 - 7,244,950 EUR and News Publishers OTHER RESEARCH PARTNERS: 2014 – (to 20 June) 3,985,500 EUR 96 bis, Rue Beaubourg International Press Institute (IPI), Vienna Source: Association of Journalists of Macedonia (2015) “Assessment of Media System in Macedonia” 75003 Paris, France International Academy - International Media www.wan-ifra.org Center (IA-IMC), Vienna International Academy (IA), Belgrade WAN-IFRA CEO: Vincent Peyrègne PROJECT PARTNERS: Center for International Media Assistance Soft Censorship in Macedonia: Bad PROJECT MANAGER: National Endowment for Democracy Practices, Bad Faith, is one of a series in the Mariona Sanz Cortell 1025 F Street, N.W., 8th Floor ongoing project on soft censorship around the Washington, DC 20004, USA world. Country reports on Hungary, Malaysia, EDITOR: www.cima.ned.org Mexico, Montenegro and Serbia were issued in Thomas R. Lansner 2013-15, as well as a global overview, Soft Open Society Justice Initiative Censorship, Hard Impact, written by Thomas R PRINCIPAL RESEARCHER: 224 West 57th Street Lansner, who also edited this report and is South East Europe Media Organisation New York, New York 10019, USA general editor for the series. (SEEMO), Vienna www.opensocietyfoundations.org www.seemo.org -

USAID Municipal Climate Change Strategies Project (MCCSP) Implemented By: Milieukontakt Macedonia Final Program Performance Repo

USAID Municipal Climate Change Strategies Project (MCCSP) Implemented by: Milieukontakt Macedonia Final Program Performance Report Cooperative Agreement #: AID-165-A-1 2-00008 Submitted to: Jennifer Connolly, Agreement Officer’s Representative, (DEC) Development experience clearinghouse Bureau for management/Office of chief information officer/Knowledge Management Divisions (M/CIO/KM) USAID agency for International Development 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W Washington D.C. 20523 Skopje, Macedonia May 25, 2017 Submitted by: Igor Slavkoski, MCCSP Chief of Party Milieukontakt Macedonia 1 COMPENDIUM THE USAID MUNICIPAL CLIMATE CHANGE STRATEGIES PROJECT Project Report Prepared by: Milieukontakt Macedonia Authors: Maja Markovska; Igor Slavkoski; Blagica Andreeva; Stole Georgiev; Denis Zernovski; Radmila Slavkova 2 Contents I. List of Abbreviations ..................................... 6 II. Executive Summary ...................................... 7 Green Agenda ........................................................................................................ 9 Three international Green Agenda Conferences ............................................................ 9 Capacity Building ..................................................................................................... 9 Visibility .................................................................................................................. 11 III. Introduction ............................................... 12 IV. About Milieukontakt Macedonia .................... 12 -

14 Dana U Medijima“ Uređuju Marin I Goran Cetinić Koje Možete Kontaktirati Putem Mail Adrese [email protected]

Broj 35 4‐17. avgust 2012. Sadržaj Kablovska TV sve gledanija – RRA ne reaguje na zahteve regionalnih stanica – Apelacioni sud doneo odluku korisnu za medijski sektor – Niovinarska udruženja: Najava novog zakona o informisanju simboličan gest – Adrijana Mirković: „Đilas kao Berluskoni“ – ASMEDI poziva Dačića i Petkovića na dijalog – Gordana Predić, kandidat za državnog sekretara za medije – Kurir: Tijanić ostaje na čelu RTS-a – Evropska radiodifuzna unija operativno pomaže RTS – Milanović nakon 10 godina izlazi iz zatvora – Miloš Vasić oslobođen optužbe – 70 novinara ubijeno u prvih 6 meseci ove godine – Lasla Šaša na izlasku iz zatvora dočekale kolege – Pomilovanje Šaša podržale medijske institucije – Nikolić primio Šaša . Novo upozorenje UNS, NUNS-a, Poverenika za informacije i Ombudsmana na nekorektan tretman maloletnih žrtava krivičnih dela u pojedinim medijima – Blic ponovo prekršio etičke norme, tvrdi NUNS – Vujanov: Neprofesionalni sportski reporteri RTS-a – Otašević: Kablovska TV „Ju” ima kvalitetan filmski program – Međunarodni medijski samit za mlade u Beogradu - Mandica Knežević, novinarka Radija Novi Sad, dobila nagradu „Ana Njemogova Kolarova“ – U Mavrovu BIRN škola istraživačkog novinarstva – Seminar „Upravljanje projektnim ciklusom“ – NED poziva kandidate za stipendije – Šaš posetio UNS – Prema podacima ABC oditora po štampanom i prodatom tiražu Večernje novosti su na prvom mestu – TV Apolo traži glavnog urednika - Preminuo poznati šahista i novinar Svetozar Gligorić . Kurir: Tompson vlasnik Narodnog radija – Novinari u TV Mozaik nastavljaju štrajk – Samo 18% korisnika Interneta kupuje elektronski – Očekuje se dolazak PayPal-a u Srbiju – Nova vrsta virtuelnog oglašavanja – Tri emitera ilegalno u Pčinjskom okrugu – Sindikat traži ispitivanje zakonitosti stečaja TV Čačak – Potpisnici Kragujevačke inicijative traže sprovođenje medijske strategije – Još se nije javio novi suvlasnik Politike – Zbog snimanja Žikine šarenice bez struje deo Kuršumlije . -

Broadcasting Council of the Republic of Macedonia

Broadcasting Council of the Republic of Macedonia ANALYSIS OF THE MARKET OF BROADCASTING ACTIVITY for 2008 Drafted by the Sector for research and long-term development of the Broadcasting Council of RM Skopje, November 2009 1 C o n t e n t s PREFACE 3 1. SUMMARY OF THE ANALYSIS 5 2. TELEVISION MARKET 11 2.1. Key changes on the television market 11 2.2. Television industry 17 2.2.1. Types of receiving the TV signal and participants on the market 2.2.2. Income in the television industry 2.2.3. Structure of the expenses 2.2.4. Investment 2.2.5. Liabilities/Debts 2.2.6. Working results 2.2.7. Employees 3. RADIO MARKET 47 3.1. Key changes on the radio market 47 3.2. Radio industry 50 3.2.1. Types of receiving the radio signal and participants on the market 3.2.2. Income in the radio industry 3.2.3. Structure of the expenses 3.2.4. Investment 3.2.5. Liabilities/Debts 3.2.6. Working results 3.2.7 Employees 4. ADVERTISING MARKET 75 4.1. Gross and net income from advertising 75 4.2. Comparative indicators for the advertising markets in other countries 4.3. Main advertising industries and companies in the TV sector 4.4. Share in the net income from advertising and share in the TV and radio ratings 5. OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE 86 5.1. Types of capital integration in the broadcasting sector 5.2. Changes in the ownership structure in 2007 5.3. Ownership structure of the broadcasters 2 3 Preface For the purpose of obtaining full-scale information on the current situation of the broadcasting industry, the Broadcasting Council conducts an annual analysis of the market of broadcasting activity.