Catalogue 2009/10 ECM Paul Griffiths Bread and Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 10-6-1982 The aC rroll News- Vol. 67, No. 3 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 67, No. 3" (1982). The Carroll News. 670. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/670 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vol. OINo. 3 October 6. 1982 tlrbe <!Carroll _jf}etus John Carroll University University Heights, Ohio 44118 Student Union proposes renewal of Stunt Night Will Stunt Night return? This Stunt Night was considered recent. Student Union meeting. tion. laborating data of the past is one of the more popular ques· one of the best sources of class JCU alumni have suggested Student Union President stunt nights, and devising tions pervading the halls of unity, and received significant that Stunt Night be brought Chris Miller says that he is wiU· ground rules which will im· Carroll as of late. yearbook coverage. back, according to senior class ing to lli1ten to any ideas prove future stunt nights. "What is Stunt Night?" you Unfortunately, some of the representative Jim Garvey. students have regarding the Stunt Night was once a main might ask. Actually, it was one material in the skits, which was Presently, the newly-formed return of this much-missed at· event on campus to bring of the bigger events here until intended for the coUege·level Investigative Committee, com· traction. -

Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World

1 Chapter Seven Cold Commodities: Discourses of Decay and Purity in a Globalised Jazz World Haftor Medbøe Since gaining prominence in public consciousness as a distinct genre in early 20th Century USA, jazz has become a music of global reach (Atkins, 2003). Coinciding with emerging mass dissemination technologies of the period, jazz spread throughout Europe and beyond via gramophone recordings, radio broadcasts and the Hollywood film industry. America’s involvement in the two World Wars, and the subsequent $13 billion Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe as a unified, and US friendly, trading zone further reinforced the proliferation of the new genre (McGregor, 2016; Paterson et al., 2013). The imposition of US trade and cultural products posed formidable challenges to the European identities, rooted as they were in 18th-Century national romanticism. Commercialised cultural representations of the ‘American dream’ captured the imaginations of Europe’s youth and represented a welcome antidote to post-war austerity. This chapter seeks to problematise the historiography and contemporary representations of jazz in the Nordic region, with particular focus on the production and reception of jazz from Norway. Accepted histories of jazz in Europe point to a period of adulatory imitation of American masters, leading to one of cultural awakening in which jazz was reimagined through a localised lens, and given a ‘national voice’. Evidence of this process of acculturation and reimagining is arguably nowhere more evident than in the canon of what has come to be received as the Nordic tone. In the early 1970s, a group of Norwegian musicians, including saxophonist Jan Garbarek (b.1947), guitarist Terje Rypdal (b.1947), bassist Arild Andersen (b.1945), drummer Jon Christensen (b.1943) and others, abstracted more literal jazz inflected reinterpretations of Scandinavian folk songs by Nordic forebears including pianist Jan Johansson (1931-1968), saxophonist Lars Gullin (1928-1976) bassist Georg Riedel (b.1934) (McEachrane 2014, pp. -

The Art of Making Mistakes

The Art of Making Mistakes Misha Alperin Edited by Inna Novosad-Maehlum Music is a creation of the Universe Just like a human being, it reflects God. Real music can be recognized by its soul -- again, like a person. At first sight, music sounds like a language, with its own grammatical and stylistic shades. However, beneath the surface, music is neither style nor grammar. There is a mystery hidden in music -- a mystery that is not immediately obvious. Its mystery and unpredictability are what I am seeking. Misha Alperin Contents Preface (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Introduction Nothing but Improvising Levels of Art Sound Sensitivity Fairytales and Fantasy Music vs Mystery Influential Masters The Paradox: an Improvisation on the 100th Birthday of the genius Richter Keith Jarrett Some thoughts on Garbarek (with the backdrop of jazz) The Master on the Pedagogy of Jazz Improvisation as a Way to Oneself Main Principles of Misha's Teachings through the Eyes of His Students Words from the Teacher to his Students Questions & Answers Creativity: an Interview (with Inna Novosad-Maehlum) About Infant-Prodigies: an Interview (with Marina?) One can Become Music: an Interview (with Carina Prange) Biography (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Upbringing The musician’s search Alperin and Composing Artists vs. Critics Current Years Reflections on the Meaning of Life Our Search for Answers An Explanation About Formality Golden Scorpion Ego Discography Conclusion: The Creative Process (by Inna Novosad-Maehlum) Preface According to Misha Alperin, human life demands both contemplation and active involvement. In this book, the artist addresses the issues of human identity and belonging, as well as those of the relationship between music and musician. -

Jazzecho 2 04 RZ Rawa1

Ausgabe 2 Jahrgang 7 Sommer 2004 „Die Jugend wird an die Jungen verschwendet.“ Kenny Barron (60) im Gespräch mit Steve Kuhn (66) Call & Response, Seite 9 Aktuelle News, Tourdaten und Neuerscheinungen jeden Freitag neu unter http://www.jazzecho.de world’s best-sounding newspaper Intro Classics Feedback Details Call & Response Porträt Planet Jazz Mix Die wichtigsten Die schönsten Swingende Das kleinste Zukunft mit Vertraut Naturellement Seite 12 gut, Neuerscheinungen Reissues Milchbärte Gedruckte Vergangenheit fremdartig Helena alles gut Was gibt’s Legendäre LPs, die oft noch nie Die Presseschau im JazzEcho Jazzfans sind anders als andere Diesmal im Seit fast 35 Jahren geht der Diesmal auf der Seite, die die Zum Schluss Neues? Und auf CD erschienen sind oder – diesmal mit Beiträgen zu Diana Menschen: Sie haben einen JazzEcho- brasilianische Superstar und Welt des Jazz aus aller Welt von wird unser Jazz- was ist davon lange vergriffen waren, bringt Krall, Frank Chastenier, Torun besseren Geschmack, nicht nur Doppel- Volksheld Caetano Veloso mit dem allen Seiten beleuchtet: Neue verständnis gut? Unter die Serie LPR nach und nach Eriksen und Jamie Cullum, den was Musik angeht, und sie haben interview: Die Gedanken schwanger, ein Album Aufnahmen, unter anderem von noch einmal anderem neue heraus, und das in besonders die „New York Times“ einen einen ausgeprägten Sinn für Pianisten Kenny nicht auf Portugiesisch, sondern João Gilberto und der ebenso extrabreit. Da Aufnahmen von liebevoller Ausstattung: Im Papp- „ungezogenen Post-Punk-Rocker“ Details. Darum widmen wir ihnen Barron und auf Englisch aufzunehmen – ein belgisch-portugiesischen wie passen dann John Scofield Digipak sieht die CD fast aus wie nannte, „verblüfft von den Heft für Heft drei volle Seiten mit Steve Kuhn Experiment, das geringere Musiker schönen Helena sowie eine auch Masters und Al Jarreau. -

«Solo Duo Trio» – Christian Zehnder Di 22.05

«Solo Duo Trio» – Christian Zehnder Di 22.05. / Mi 23.05. / Do 24.05.2018 Mitte Februar 2017 feierte Christian Zehnders Solo «songs from new space mountain» im Gare du Nord seine Uraufführung. Alle drei Premieren-Vorstellungen waren ausverkauft. Die Resonanz auf die Performance war so gross, dass eine Wiederaufnahme schon nach der Premiere im Raum stand. Im Mai 2018 bietet sich nun dem Publikum die Möglichkeit, das Solo «songs from new space mountain» nochmals (oder erstmals) zu sehen – darüber hinaus tritt er auch in zwei Formationen auf, die hier noch kaum bekannt sind: im Duo mit dem Drehorgelspieler Matthias Loibner und im Trio mit dem Hornisten Arkady Shilkloper und dem Pianisten John Wolf Brennan. Di 22.05.18 20:00 «songs from new space mountain» – Christian Zehnder Solo Eine Werkschau und Reise durch den unvergleichlichen Klangkosmos von Christian Zehnder – ein ausserirdischer Heimatabend (Wiederaufnahme) Mit neuen Kompositionen und Werken aus den letzten 20 Jahren führt uns der Stimmenkünstler Christian Zehnder in eine ganz eigenständige, archaische und geradezu ausserirdische Welt der Laute, die völlig ohne Worte auskommt. Der eigenwillige Schweizer Musiker, welcher schon mit dem Duo Stimmhorn die alpine Musik neu aufmischte und Kultstatus geniesst, lässt sich in seiner Vielfalt nicht einordnen. Auch muss man ihn live gesehen haben. Erst dann erschliesst sich sein zwischen Musik, Performance und visueller Ausdruckskraft angelegtes Werk in seiner ganzen Kraft und Faszination. Seit 25 Jahren stehen meine meisten künstlerischen Arbeiten im alpinen Kontext und einer Vision einer neuen klanglichen Utopie der Heimat. Daraus ist bis heute ein sehr persönliches und dennoch breitgefächertes Werk entstanden, welches die menschliche Stimme zwischen alpinem und urbanem Lebensraum zu befragen versucht und in den verschiedensten Disziplinen seine jeweilige Form findet. -

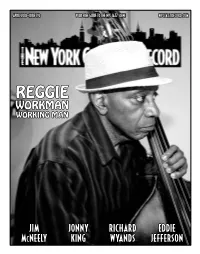

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Jack Dejohnette's Drum Solo On

NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

June 2020 Volume 87 / Number 6

JUNE 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 6 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

MMDG Pepperland Program Insert.Indd

The Company MICA BERNAS, originally from Manila, Philippines, received performing Skylight, a classic work by choreographer Laura Dean. He debuted her training at the Cultural Center of the Philippines Dance with MMDG in 2007 and became a company member in 2009. Estrada would School. She later joined Ballet Philippines as member of the like to thank God, his family, and all who support his passion. corps de ballet, performing as a soloist from 2001-2006. Since moving to New York in 2006, Bernas has worked with Marta COLIN FOWLER (music director, organ/harpsichord) began Renzi Dance, Armitage Gone Dance, Gallim Dance, Barkin/ his musical study at the age of 5 in Kansas City and went on to Selissen Project, and Carolyn Dorfman Dance (2007-2013). She study at the prestigious Interlochen Arts Academy. He contin- was a guest artist with the Limón Dance Company, performing ued his education at The Juilliard School, where he received his at the 2013 Bienal Internacional de Danza de Cali in Bogotá, Colombia; Lincoln Bachelor of Music in 2003 and his Master of Music in 2005. Center’s David H. Koch Theater; and at The Joyce Theater for the company’s 70th While at Juilliard, he studied piano with Abbey Simon, organ Anniversary in 2015. Bernas also teaches at the Limón Institute and has been with Gerre Hancock and Paul Jacobs, harpsichord with Lionel on the faculty for BIMA at Brandeis University since 2011. She joined MMDG Party, and conducting with James dePriest and Judith Clurman. as an apprentice in January 2017 and became a full time company member in A versatile musician and conductor, Fowler works in many areas of the music August 2017. -

Norway's Jazz Identity by © 2019 Ashley Hirt MA

Mountain Sound: Norway’s Jazz Identity By © 2019 Ashley Hirt M.A., University of Idaho, 2011 B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Musicology. __________________________ Chair: Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz __________________________ Dr. Bryan Haaheim __________________________ Dr. Paul Laird __________________________ Dr. Sherrie Tucker __________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong-Cruz The dissertation committee for Ashley Hirt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: _____________________________ Chair: Date approved: ii Abstract Jazz musicians in Norway have cultivated a distinctive sound, driven by timbral markers and visual album aesthetics that are associated with the cold mountain valleys and fjords of their home country. This jazz dialect was developed in the decade following the Nazi occupation of Norway, when Norwegians utilized jazz as a subtle tool of resistance to Nazi cultural policies. This dialect was further enriched through the Scandinavian residencies of African American free jazz pioneers Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and George Russell, who tutored Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. Garbarek is credited with codifying the “Nordic sound” in the 1960s and ‘70s through his improvisations on numerous albums released on the ECM label. Throughout this document I will define, describe, and contextualize this sound concept. Today, the Nordic sound is embraced by Norwegian musicians and cultural institutions alike, and has come to form a significant component of modern Norwegian artistic identity. This document explores these dynamics and how they all contribute to a Norwegian jazz scene that continues to grow and flourish, expressing this jazz identity in a world marked by increasing globalization. -

Paul Bley / NHØP Mp3, Flac, Wma

Paul Bley Paul Bley / NHØP mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Paul Bley / NHØP Country: Netherlands Released: 1979 Style: Free Jazz, Avantgarde MP3 version RAR size: 1268 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1533 mb WMA version RAR size: 1487 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 814 Other Formats: VOC MP1 ADX AC3 APE VQF MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Meeting A1 6:03 Composed By – Paul Bley Mating Of Urgency A2 3:51 Composed By – Paul Bley Carla A3 4:21 Composed By – Paul Bley Olhos De Gato A4 5:33 Composed By – Carla Bley Paradise Island B1 2:20 Composed By – Paul Bley Upstairs B2 3:07 Composed By – Paul Bley Later B3 5:23 Composed By – Paul Bley Summer B4 4:06 Composed By – Paul Bley Gesture Without Plot B5 5:33 Composed By – Annette Peacock Credits Acoustic Bass – Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen Design – Václav Blažek Photography By – Ib Skovgaard Piano – Paul Bley Producer – Nils Winther Notes A1 to A3, B3 to B5 recorded in Copenhagen June 24, 1973 and A4, B1, B2 recorded in Copenhagen July 1, 1973. Made in Holland on labels. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Paul Bley, NHØP* - Paul Bley, SCS 1005 Paul Bley / NHØP (LP, SteepleChase SCS 1005 Denmark 1973 NHØP* Album) Paul Bley / NHØP* - Paul Bley / Inner City IC 2005 Paul Bley . NHØP (LP, IC 2005 US 1976 NHØP* Records Album) Paul Bley, NHØP* - Paul Bley, UPS-2158-S Paul Bley / NHØP (LP, SteepleChase UPS-2158-S Japan 1982 NHØP* Album, RE) Paul Bley, NHØP* - Paul Bley, SCS 1005 Paul Bley / NHØP (LP, SteepleChase SCS 1005 Denmark Unknown NHØP* Album) Paul Bley, NHØP* - Paul Bley, 15PJ-2006 Paul Bley / NHØP (LP, SteepleChase 15PJ-2006 Japan 1973 NHØP* Album) Related Music albums to Paul Bley / NHØP by Paul Bley Paul Bley - Synth Thesis Paul Bley - Alone, Again Paul Bley - Footloose Carla Bley - The Best Of Big Band Paul Bley & Scorpio - Paul Bley & Scorpio Paul Bley - Turns Paul Bley Trio - The Nearness Of You Jimmy Giuffre Trio With Paul Bley & Steve Swallow - Carla Paul Bley - Paul Bley Paul Bley - Open, To Love. -

Publicacion7135.Pdf

BIBLIOTECA PÚBLICA DE ALICANTE BIOGRAFÍA Roy Haynes nació el 13 de marzo de 1925 en Boston, Massachusetts. A finales de los años cuarenta y principios de los cincuenta, Roy Haynes tuvo la clase de aprendizaje que constituiría el sueño de cualquier músico actual: sentarse en el puesto de baterista y acompañar al gran Charlie Parker. Ahora, cincuenta años después, y tras haber tocado con todos los grandes del jazz: Thelonius Monk, Miles Davis, o Bud Powell, todavía coloca sus grabaciones en la cima de las listas de las revistas especializadas en jazz. Este veterano baterista, comenzó su andadura profesional en las bigbands de Frankie Newton y Louis Russell (1945-1947) y el siguiente paso fue tocar entre 1947 y 1949 con el maestro el saxo tenor, Lester Young. Entre 1949 y 1952, formo parte del quinteto de Charlie Parker y desde ese privilegiado taburete vio pasar a las grandes figuras del bebop y aprender de ellas. Acompañó a la cantante Sarah Vaughan, por los circuitos del jazz en los Estados Unidos entre 1953 y 1958 y cuando finalizó su trabajo grabo con Thelonious Monk, George Shearing y Lennie Tristano entre otros y ocasionalmente sustituía a Elvin Jones en el cuarteto de John Coltrane. Participó en la dirección de la Banda Sonora Original de la película "Bird" dirigida por Clint Eastwood en 1988 y todavía hoy en activo, Roy Haynes, es una autentica bomba dentro de un escenario como pudimos personalmente comprobar en uno de sus últimos conciertos celebrados en España y mas concretamente en Sevilla en el año 2000. En 1994, Roy Haynes recibió el premio Danish Jazzpar, que se concede en Dinamarca.