Tourism and Heritage in the Little Karoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Details Charges Charges

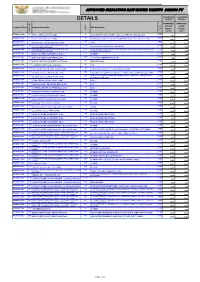

APPROVED IRRIGATION RAW WATER TARIFFS 2020/21 FY CONSUMPTIVE CONSUMPTIVE DETAILS CHARGES CHARGES APPROVED APPROVED 2019/20 2020/21 Regional Office Scheme Description SMP Description Charges Charges Sector SMP SMP ID Scheme IDScheme (c/m³) (c/m³) Western Cape 6 4 IRR BERG RIVER (VOELVLEI DAM) FROM TWENTY-FOUR RIVERS CANAL TO THE IRRIGATION BOARD 1,52 1,52 Western Cape 6 127 IRR BERG RIVER (VOELVLEI DAM) IRRIGATION FROM BERG RIVER DOWNSTREAM OF THE VOELVLEI DAM 13,22 13,22 Western Cape 9 48 IRR BRAND RIVER (MIERTJIESKRAAL DAM) DAM 11,75 11,75 10 BREEDE RIVER (GREATER BRANDVLEI AND 116 IRR Western Cape BREEDE RIVER CONSERVATION BOARD KWAGGASKLOOF DAMS) 3,46 3,46 Western Cape 10 BREEDE RIVER (GREATER BRANDVLEI AND 417 PURCHASED WATER RIGHTS & OTHER BOARDS (EXCLUDING BREEDE RIVER IRR KWAGGASKLOOF DAMS) CONSERVATION BOARD) 6,24 6,33 Western Cape 12 51 IRR BUFFALO RIVER (FLORISKRAAL-DAM) SCHEME 7,44 7,64 Western Cape 12 420 IRR BUFFALO RIVER (FLORISKRAAL-DAM) C VAN WYK PREFERENTIAL RIGHT 7,44 7,64 Western Cape 13 52 IRR BUFFELJAGTS RIVER (BUFFELJAGTS DAM) FROM THE DAM 7,37 7,60 Western Cape 17 55 IRR CORDIERS RIVER (OUKLOOF DAM) DAM 11,12 11,12 Western Cape 25 62 IRR DUIVENHOKS RIVER (DUIVENHOKS DAM) FROM DUIVENHOKS RIVER (DUIVENHOKS DAM) 7,51 7,72 Western Cape 26 605 IRR ELANDS RIVER (ELANDS-KLOOF DAM) EXISTING DEVELOPMENT FROM THE ELANDS RIVER (ELANDS-KLOOF DAM) 0,76 0,88 26 606 NEW DEVELOPMENT (DAM COSTS INCLUDED) FROM THE ELANDS RIVER IRR Western Cape ELANDS RIVER (ELANDS-KLOOF DAM) (ELANDS-KLOOF DAM) 9,05 9,29 Western Cape 31 68 IRR GAMKA -

History of the Oudtshoorn Research Farm 50 Years

Oudtshoorn Research Farm: Oudtshoorn Research Oudtshoorn Research Farm: Celebrating 50 years of the world’s firstOstrich Research Farm (1964 – 2014) Celebrating 50 years (1964 – 2014) ISBN: 978-0-9922409-2-9 PRINT | DIGITAL | MOBILE | RADIO | EVENTS | BRANDED CONTENT Your communications partner in the agricultural industry Oudtshoorn Research Farm: Celebrating 50 years of the world’s first Ostrich Research Farm (1964 – 2014) Editors: Schalk Cloete, Anel Engelbrecht, Pavarni Jorgensen List of contributors: Minnie Abrahams Ters Brand Zanell Brand Willem Burger Schalk Cloete Anel Engelbrecht Derick Engelbrecht Attie Erasmus Ernst Guder Samuel Jelander Pavarni Jorgensen Kobus Nel Phyllis Pienaar Andre Roux Piet Roux Ansie Scholtz Jan Smit Charnine Sobey Derick Swart Jan Theron Johan van der Merwe Koot van Schalkwyk Bennie Visser Toni Xaba Oudtshoorn Research Farm: Celebrating 50 years of the world’s first Ostrich Research Farm (1964 – 2014) Limited print run of 250 copies. Copyright © 2014 – Western Cape Department of Agriculture [email protected] www.elsenburg.com Private Bag X1 Elsenburg 7607 Oudtshoorn Research Farm Old Kammanassie Road Rooiheuwel Oudtshoorn 6620 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any other information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission from the author. Reproduction: Agri Connect (Pty) Ltd PO Box 1284 Pretoria, 0001 South Africa www.agriconnect.co.za Publisher Leza Putter Executive editor Pavarni Jorgensen Copy editor Milton Webber Creative design Michélle van der Walt ISBN: 978-0-9922409-2-9 Printed and bound by Fishwicks Printers, Durban, South Africa. -

South Africa Motorcycle Tour

+49 (0)40 468 992 48 Mo-Fr. 10:00h to 19.00h Good Hope: South Africa Motorcycle Tour (M-ID: 2658) https://www.motourismo.com/en/listings/2658-good-hope-south-africa-motorcycle-tour from €4,890.00 Dates and duration (days) On request 16 days 01/28/2022 - 02/11/2022 15 days Pure Cape region - a pure South Africa tour to enjoy: 2,500 kilometres with fantastic passes between coastal, nature and wine-growing landscapes. Starting with the world famous "Chapmans Peak" it takes as a start or end point on our other South Africa tours. It is us past the "Cape of Good Hope" along the beautiful bays situated directly on Beach Road in Sea Point. Today it is and beaches around Cape Town. Afterwards the tour runs time to relax and discover Cape Town. We have dinner through the heart of the wine growing areas via together in an interesting restaurant in the city centre. Franschhoek to Paarl. Via picturesque Wellington and Tulbagh we pass through the fruit growing areas of Ceres Day 3: to the Cape of Good Hope (Winchester Mansions to the enchanted Cederberg Mountains. The vastness of Hotel) the Klein Karoo offers simply fantastic views on various Today's stage, which we start right after the handover and passes towards Montagu and Oudtshoorn. Over the briefing on GPS and motorcycles, takes us once around the famous Swartberg Pass we continue to the dreamy Prince entire Cape Peninsula. Although the round is only about Albert, which was also the home of singer Brian Finch 140 km long, there are already some highlights today. -

Department of English And

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE Spring 2015 Newsletter Cindy Baer: An Outstanding Nurturer of Table of Contents Success By Aaron Thein and Giselle Tran Cindy Baer: An Outstanding Nurturer of Success 1 he average preschooler will begin to use their motor skills and learn to have fun by running Robert Cullen: Leaving a Lasting around, jumping on one foot, or skipping. Dr. Impression in SJSU History 2 T Cindy Baer, how- ever, was not an av- Spotlight on Visiting Professor Andrew Lam 4 erage preschooler. “I’ve known since Celebrating a Career: Dr. Bonnie Cox is Retiring 5 I was five years old that I wanted to be Dr. Katherine Harris Publishes New Book on a teacher,” she says, the British Literary Annual 6 having developed a hobby of writing Student Success Funds Awarded to Professional quizzes for her and Technical Writing Program 7 imaginary students at that age. She re- alized her dream of Spartans’ Steinbeck 8 becoming a teacher when she received The English Department Goes to Ireland 10 her MA in 1983 and her PhD in 1994 from the University of Washington National Adjunct Walkout Day 11 in Seattle. And now, in March 2015, she has been given the Outstanding Lecturer Award of 2015—an award Now Hiring: Writing Specialists 12 that considers eligible lecturers from all departments of SJSU—as well as hired in the tenure-track position of Welcoming Doctor Ryan Skinnell 14 Assistant Writing Programs Administrator. Upon receiving all the good news, Dr. Baer admits Reading Harry Potterin Academia 15 it felt surreal. -

Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport (DCAS) Annual Report 2018/19

Annual Report 2018/2019 Department of Cultural Affairs and Sport Western Cape Government Vote 13 Annual Report 2018/2019 ISBN: 978-0-621-47425-1 1 Contents Part A ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Departmental General Information ............................................................................................. 5 2. List of abbreviations/acronyms ..................................................................................................... 6 3. Foreword ........................................................................................................................................... 9 4. Report of the Accounting Officer .............................................................................................. 10 5. Statement of Responsibility and Confirmation of Accuracy of the Annual Report ......... 15 6. Strategic overview ........................................................................................................................ 16 6.1. Vision ................................................................................................................................................ 16 6.2. Mission .............................................................................................................................................. 16 6.3. Values ............................................................................................................................................. -

Introduction the Quest the Process and Resources

Name: Period: Date: Of Mice and Men WebQuest Introduction You are about to embark on a WebQuest to discover what life was like in the 1930s. Of Mice and Men is set in California during the Great Depression. It follows two migrant workers, George and Lennie, as they struggle to fulfill their dreams. In order to better understand their plight, you will be exploring several websites to increase your background knowledge before getting into the book. Check out the websites listed below to help you answer the following questions. The Quest What are the background issues that led to Steinbeck's writing of this novella about profound friendship and social issues? First complete the Great Depression simulation on your own to gather some background knowledge. Then begin the research with your group. The Process and Resources In this WebQuest you will be working and exploring web pages to answer questions in your designated section. Each member in your group is assigned a role. You are responsible for answering the questions for your role and sharing that information with your group. Together you will create a presentation that includes information from each group member’s research. Group Members: ____________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ My Role: __________________________________________ Name: Period: Date: Geographers: The geography of Of Mice and Men Setting in Of Mice and Men Salinas farm country John Steinbeck and Salinas, California Steinbeck Country Geographers' Questions: 1. What are the geographical features of California’s Salinas River Valley? 2. What is the Salinas Valley known as? 3. What kinds of jobs are available there? 4. -

Draft Review: Integrated Development Plan 2013/2014

DRAFT REVIEW: INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2013/2014 1 | P a g e CONTACT DETAILS: Head Office: 32 Church Street Ladismith 6655 Tel number: 028 55 11 023 Fax 028 55 11 766 Email [email protected] Website www.kannaland.gov.za 2 | P a g e COUNCIL: Position Party EXECUTVE MAYOR Aldermen Jeffrey Donson Ward Councillor ICOSA SPEAKER Councillor Hyrin Ruiters Ward Councillor ICOSA DEPUTY MAYOR Councillor: Phillipus Antonie PR Councillor ANC Ward Councillor Councillor Albie Rossouw DA 3 | P a g e CHIEF WHIP Councillor Werner Meshoa Ward Councillor ICOSA Councillor Lorraine Claassen PR Councillor ANC Councillor Leona Willemse PR Councillor DA 4 | P a g e MANAGEMENT: 5 | P a g e CONTENTS: Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Foreword by Mayor 9 1.2 Foreword by Municipal Manager 10 1.3 Overview of the Integrated Development Plan 11-19 Section 2: Kannaland Profile 2.1 Demographic Data 21-22 2.2 Population 23 2.2.1 Population Demographics 23 2.2.2 Household Data 24 2.2.3 Education 24 2.2.4 Crime 25 2.2.5 Health 28 2.3 Analyses Phase 2.4 Basic Services 31 2.5 Good Governance 34-47 2.6 Transformation 2.7 Local Economic Development 48-68 2.8 Financial Viability 2.9 Projects Register 68-69 Section 3: Strategic Thrust 3.1 Strategic Thrust 3.2 Vision 70 3.3 Mission 70 3.4 Objectives 71-79 3.5 Key Performance Areas 79 3.6 Key Performance Indicators 79 3.7 Cross Sectorial Alignment 80-95 Section 4: Projects 97-102 Section 5: Integrated Programmes 5.1 Operation and Maintenance 5.2 Spatial Development Framework 5.3 Performance Management System 5.4 Monitoring and Evaluation -

Regional Development Profile: Eden District 2010 Working Paper

Provincial Government Western Cape Provincial Treasury Regional Development Profile: Eden District 2010 Working paper To obtain additional information of this document, please contact: Western Cape Provincial Treasury Directorate Budget Management: Local Government Private Bag X9165 7 Wale Street Cape Town Tel: (021) 483-3386 Fax: (021) 483-4680 This publication is available online at http://www.capegateway.gov.za Contents Chapter 1: Eden District Municipality Introduction 3 1. Demographics 4 2. Socio-economic Development 8 3. Labour 18 4. Economy 23 5. Built Environment 26 6. Finance and Resource Mobilisation 37 7. Political Composition 41 8. Environmental Management 41 Cautionary Note 47 Chapter 2: Kannaland Local Municipality Introduction 51 1. Demographics 52 2. Socio-economic Development 55 3. Labour 63 4. Economy 68 5. Built Environment 70 6. Finance and Resource Mobilisation 74 7. Governance and Institutional Development 77 Cautionary Note 78 Chapter 3: Hessequa Local Municipality Introduction 83 1. Demographics 84 2. Socio-development 87 3. Labour 95 4. Economy 100 5. Built Environment 102 6. Finance and Resource Mobilisation 107 7. Political Composition 110 Cautionary Note 111 i REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROFILE 2010 Chapter 4: Mossel Bay Local Municipality Introduction 115 1. Demographics 116 2. Socio-development 120 3. Labour 130 4. Economy 135 5. Built Environment 137 6. Finance and Resource Mobilisation 141 7. Political Composition 145 8. Environmental Management 145 Cautionary Note 149 Chapter 5: George Local Municipality Introduction 153 1. Demographics 154 2. Socio-economic Development 158 3. Labour 167 4. Economy 172 5. Built environment 174 6. Finance and Resource Mobilisation 179 7. Political Composition 182 Cautionary Note 183 Chapter 6: Oudtshoorn Local Municipality Introduction 187 1. -

Cape Librarian May/June 2015 | Volume 59 | No

Cape Librarian May/June 2015 | Volume 59 | No. 3 Kaapse Bibliotekaris MJ15 Cover Outside Inside.indd 2 2015/06/29 01:36:53 PM contents | inhoud FEATURES | ARTIKELS Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming 13 Neil Gaiman COLUMNS | RUBRIEKE BOOK WORLD | BOEKWÊRELD Uit die joernalistiek gebore: ‘n skrywer vir méér as vermaak 18 Francois Verster Twee onblusbare geeste 20 Francois Verster Out and about 23 Sabrina Gosling Book Reviews | Boekresensies 32 Compiled by Book Selectors / Saamgestel deur Boekkeurders SPOTLIGHT ON SN | KOLLIG OP SN For health’s sake … 36 Dalena le Roux CRITICAL ISSUES | EZIDL’ UBHEDU: IILWIMI ZABANTSUNDU Amakhamandela oncwadi lwabantsundu 38 nguXolisa Tshongolo THE LAST WORD | DIE LAASTE WOORD Die essensie van ’n resensie 39 Francois Bloemhof NEWS | NUUS between the lines / tussen die lyne 2 people / mense 4 libraries / biblioteke 4 books and authors / skrywers en boeke 8 literary awards / literêre toekennings 8 miscellany / allerlei 9 40 years … 12 COVER | VOORBLAD Sindiwe Magona, a writer, poet, dramatist, storyteller, actress and motivational speaker, whose Beauty’s gift was shortlisted for the 2009 Commonwealth Writer’s Prize (Africa). Sindiwe Magona is ’n skrywer, digter, dramaturg, storieverteller, aktrise, en motiveringspreker. Haar boek, Beauty’s gift, was op die kortlys vir die 2009 Commonwealth Writer’s Prize (Africa). MJ15 Cover Outside Inside.indd 3 2015/06/29 01:36:55 PM editorial this month. Enjoy and don’t forget to snuggle up with a book at the first opportunity! it is alweer sulke tyd. Dis nat, winderig en ysig koud en al waarvan mens droom is om onder daardie lekker warm Ddonserige kombers in te kruip met een van die ‘boeke wat ’n mens nog moet lees voordat jy doodgaan’ en ’n stomende koppie tee. -

Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study For

Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study for South Africa Using Systematic, Historical and Palaeoflood Data Pilot Study – Catchment Management Area 15 by D van Bladeren, P K Zawada and D Mahlangu SRK Consulting & Council for Geoscience Report to the Water Research Commission on the project “Statistical Based Regional Flood Frequency Estimation Study for South Africa using Systematic, Historical and Palaeoflood Data” WRC Report No 1260/1/07 ISBN 078-1-77005-537-7 March 2007 DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION During the past 10 years South Africa has experienced several devastating flood events that highlighted the need for more accurate and reasonable flood estimation. The most notable events were those of 1995/96 in KwaZulu-Natal and north eastern areas, the November 1996 floods in the Southern Cape Region, the floods of February to March 2000 in the Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Eastern Cape provinces and the recent floods in March 2003 in Montagu in the Western Cape. These events emphasized the need for a standard approach to estimate flood probabilities before developments are initiated or existing developments evaluated for flood hazards. The flood peak magnitudes and probabilities of occurrence or return period required for flood lines are often overlooked, ignored or dealt with in a casual way with devastating effects. The National Disaster and new Water Act and the rapid rate at which developments are being planned will require the near mass production of flood peak probabilities across the country that should be consistent, realistic and reliable. -

Albertinia Gouritsmond Heidelberg Jongensfontein Riversdale Stilbaai

Albertinia Gouritsmond Witsand/Port Beaufort Jongensfontein Adventure & Nature Adventure & Nature Adventure & Nature Adventure & Nature Albertinia Golf Club 028 735 1654 Blue Flag Beach Blue Flag Beach Blue Flag Beach Garden Route Game Lodge 028 735 1200 Deepsea Fishing - George 082 253 8033 Pili Pili Adventure Centre 028 537 1783 Gourits River Guest Farm 082 782 0771 Deepsea Fishing - Marx 072 518 7245 Witsand Charters 028 5371248 Indalu Game Reserve 082 990 3831 Hiking (4 trails on commonage) 082 439 9089 Wine & Cuisine River Boat Cruises 073 208 2496 Drie Pikkewyne 028 755 8110 Wine & Cuisine Wine & Cuisine Wine & Cuisine Culture & Heritage Albertinia Hotel 028 735 1030 Kiewiet Restaurant 081 570 6003 Koffie & Klets Coffee Shop 084 463 2779 Fonteinhuisie Aloe Restaurant 028 735 1123 Koffie Stories 082 453 6332 Nella se Winkel 082 630 0230 Jakkalsvlei Private Cellar 028 735 2061 Oppi Map Restaurant 073 208 2496 Pili Pili Witsand Restaurant 028 537 1783 Roosterkoekhoek 028 735 1123 River Breeze Restaurant 083 233 8571 Tuinroete Wyn Boutique 028 735 1123 The Anchorage Beach Restaurant 028 537 1330 Culture & Heritage Culture & Heritage Culture & Heritage Melkhoutfontein Albertinia Museum 072 249 1244 Dutch Reformed Church 083 464 7783 Barry Memorial Church Gourits Memorial Malgas Pontoon Wine & Cuisine Lifestyle Lifestyle Lifestyle Dreamcatcher Foundation Cook-ups 028 754 3469 Alcare Aloe 028 735 1454 Gourits General Dealer 083 463 1366 WJ Crafts 084 463 2779 Culture & Heritage Aloe Ferox 028 735 2504 Isabel Boetiek 082 375 3050 St Augustine’s -

South Africa

CONTENTS 4 The First Class Difference 6 It’s all about you 7 Concierge 8 South Africa Map 10 Introducing South Africa 12 Tour Types 14 GUIDED TOURS 26 SELF DRIVE TOURS 40 RAIL TOURS 42 Blue Train 44 Rovos Rail SOUTH 46 HOTELS & SIGHTSEEING 48 Cape Town 52 Winelands & Overberg AFRICA 56 The Garden Route 60 Eastern Cape 61 Samara Game Reserve 62 Amakhala Game Reserve 63 Shamwari Game Reserve 64 KwaZulu-Natal 70 Gauteng 74 Mpumalanga 75 MalaMala Game Reserve 76 Thornybush Game Reserve 77 Sabi Sabi Game Reserve 78 Pungwe Safari Camp 80 STOPOVERS 82 Victoria Falls 86 Mauritius 90 Seychelles 92 TRANSPORT 94 AVIS Car Rental 96 Airlines 97 Important Information 98 Terms & Conditions 2 3 THE FIRST CLASS DIFFERENCE Making your holiday dreams a reality starts with understanding what really matters to you. Whether you’re a beach lover or adventurer, a lover of history and culture or the great outdoors, at one with nature or the big city; prefer luxury or authentic, being independent or part of a group. Our travel specialists will get to know what your heart most desires and then create a holiday to match. You’ll experience superb service all along the way and we’ll use our wealth of experience to create your holiday as if we were creating our own. You can be sure that before you go, whilst you are away and even when you come home, we’ll be with you every step of the way. AWARD WINNING SERVICE We were founded in 1996 with a desire to provide outstanding levels of service and customer satisfaction and this is still the case today.