Iraq's Evolving Insurgency and the Risk of Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq

Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS POLICY FOCUS 137 Rebooting U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq MICHAEL KNIGHTS THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2015 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Design: 1000colors Photo: A Kurdish fighter keeps guard while overlooking positions of Islamic State mili- tants near Mosul, northern Iraq, August 2014. (REUTERS/Youssef Boudlal) CONTENTS Acknowledgments | v Acronyms | vi Executive Summary | viii 1 Introduction | 1 2 Federal Government Security Forces in Iraq | 6 3 Security Forces in Iraqi Kurdistan | 26 4 Optimizing U.S. Security Cooperation in Iraq | 39 5 Issues and Options for U.S. Policymakers | 48 About the Author | 74 TABLES 1 Effective Combat Manpower of Iraq Security Forces | 8 2 Assessment of ISF and Kurdish Forces as Security Cooperation Partners | 43 FIGURES 1 ISF Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 10 2 Kurdish Brigade Order of Battle, January 2015 | 28 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks to a range of colleagues for their encouragement and assistance in the writing of this study. -

Refugee Status Appeals Authority New Zealand

REFUGEE STATUS APPEALS AUTHORITY NEW ZEALAND REFUGEE APPEAL NO 76505 AT AUCKLAND Before: B L Burson (Chairperson) S A Aitchison (Member) Counsel for the Appellant: D Mansouri-Rad Appearing for the Department of Labour: No Appearance Date of Hearing: 3 & 4 May 2010 Date of Decision: 14 June 2010 DECISION [1] This is an appeal against the decision of a refugee status officer of the Refugee Status Branch (RSB) of the Department of Labour (DOL) declining refugee status to the appellant, a national of Iraq. INTRODUCTION [2] The appellant claims to have a well-founded fear of being persecuted in Iraq on account of his former Ba’ath Party membership in the rank of Naseer Mutakadim, and due to his father’s position as Branch Member of the al-Amed Organisation for the Ba’ath Party in City A. He fears persecution at the hands of members of the Mahdi Army – a Shi’a militia group in Iraq, the police who collaborate with them, and the Iraqi Government that is infiltrated by militias. [3] The principal issues to be determined in this appeal are the well- foundedness of the appellant’s fears and whether he can genuinely access meaningful domestic protection. 2 THE APPELLANT’S CASE [4] What follows is a summary of the appellant’s evidence in support of his claim. It will be assessed later in this decision. Background [5] The appellant is a single man in his early-30s. He was born in Suburb A in City A. He is one of three children, the youngest of two boys. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Train and Equip Authorities for Syria: in Brief

Train and Equip Authorities for Syria: In Brief Christopher M. Blanchard Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Amy Belasco Specialist in U.S. Defense Policy and Budget January 9, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43727 Train and Equip Authorities for Syria: In Brief Summary The FY2015 continuing appropriations resolution (P.L. 113-164, H.J.Res. 124, FY2015 CR), enacted on September 19, 2014, authorized the Department of Defense (DOD) through December 11, 2014, or until the passage of a FY2015 national defense authorization act (NDAA), to provide overt assistance, including training, equipment, supplies, and sustainment, to vetted members of the Syrian opposition and other vetted Syrians for select purposes. The FY2015 NDAA (P.L. 113- 291, H.R. 3979) and the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235, H.R. 83) provide further authority and funding for the program. Congress acted in response to President Obama’s request for authority to begin such a program as part of U.S. efforts to combat the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations in Syria and to set the conditions for a negotiated settlement to Syria’s civil war. The FY2015 measures authorize DOD to submit reprogramming requests to the four congressional defense committees to transfer available funds. DOD submitted the first such reprogramming request in November 2014 under authorities provided by P.L. 113-164, and, in December, Congress approved $220 million in requested funds to begin program activities. H.R. 83 states that up to $500 million of $1.3 billion made available by the act for a new Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (CTPF) may be used to support the Syria train and equip program. -

Looking Into Iraq

Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch cc79-cover.qxp 28/07/2005 15:27 Page 2 Chaillot Paper Chaillot n° 79 In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) beca- Looking into Iraq me an autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/ESDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of the European security and defence policy. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between European experts and decision-makers at all levels. Chaillot Papers are monographs on topical questions written either by a member of the ISS research team or by outside authors chosen and commissioned by the Institute. Early drafts are normally discussed at a semi- nar or study group of experts convened by the Institute and publication indicates that the paper is considered Edited by Walter Posch Edited by Walter by the ISS as a useful and authoritative contribution to the debate on CFSP/ESDP. Responsibility for the views expressed in them lies exclusively with authors. Chaillot Papers are also accessible via the Institute’s Website: www.iss-eu.org cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 1 Chaillot Paper July 2005 n°79 Looking into Iraq Martin van Bruinessen, Jean-François Daguzan, Andrzej Kapiszewski, Walter Posch and Álvaro de Vasconcelos Edited by Walter Posch Institute for Security Studies European Union Paris cc79-Text.qxp 28/07/2005 15:36 Page 2 Institute for Security Studies European Union 43 avenue du Président Wilson 75775 Paris cedex 16 tel.: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 30 fax: +33 (0)1 56 89 19 31 e-mail: [email protected] www.iss-eu.org Director: Nicole Gnesotto © EU Institute for Security Studies 2005. -

The New Iraq: 2015/2016 Discovering Business

2015|2016 Discovering Business Iraq N NIC n a o t i io s n is al m In om in association with vestment C USINESS B Contents ISCOVERING Introduction Iraq continues as a major investment opportunity 5 Messages - 2015|2016 D - 2015|2016 Dr. Sami Al-Araji: Chairman of the National Investment Commission 8 RAQ HMA Frank Baker: British Ambassador to Iraq 10 I Baroness Nicholson of Winterbourne: Executive Chairman, Iraq Britain Business Council 12 EW N Business Matters HE Doing business in Iraq from a taxation perspective - PricewaterhouseCoopers 14 T Doing business in Iraq - Sanad Law Group in association with Eversheds LLP 20 Banking & Finance Citi has confidence in Iraq’s investment prospects - Citi 24 Common ground for all your banking needs - National Bank of Iraq 28 Iraq: Facing very challenging times - Rabee Securities 30 2005-2015, ten years stirring the sound of lending silence in Iraq - IMMDF 37 Almaseer - Building on success - Almaseer Insurance 40 Emerging insurance markets in Iraq - AKE Insurance Brokers 42 Facilitating|Trading Organisations Events & Training - Supporting Iraq’s economy - CWC Group 46 Not just knowledge, but know how - Harlow International 48 HWH shows how smaller firms can succeed in Iraq - HWH Associates 51 The AMAR International Charitable Foundation - AMAR 56 Oil & Gas Hans Nijkamp: Shell Vice President & Country Chairman, Iraq 60 Energising Iraq’s future - Shell 62 Oil production strategy remains firmly on course 66 Projects are launched to harness Iraq’s vast gas potential 70 Major investment in oilfield infrastructure -

Reimagining US Strategy in the Middle East

REIMAGININGR I A I I G U.S.S STRATEGYT A E Y IIN THET E MMIDDLED L EEASTS Sustainable Partnerships, Strategic Investments Dalia Dassa Kaye, Linda Robinson, Jeffrey Martini, Nathan Vest, Ashley L. Rhoades C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA958-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0662-0 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover composite design: Jessica Arana Image: wael alreweie / Getty Images Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface U.S. -

Towards a Policy Framework for Iraq's Petroleum Industry and An

Towards a Policy Framework for Iraq’s Petroleum Industry and an Integrated Federal Energy Strategy Submitted by Luay Jawad al-Khatteeb To the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Politics In January 2017 The thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature ......................................................... i Abstract: The “Policy Framework for Iraq’s Petroleum Industry” is a logical structure that establishes the rules to guide decisions and manage processes to achieve economically efficient outcomes within the energy sector. It divides policy applications between regulatory and regulated practices, and defines the governance of the public sector across the petroleum industry and relevant energy portfolios. In many “Rentier States” where countries depend on a single source of income such as oil revenues, overlapping powers of authority within the public sector between policy makers and operators has led to significant conflicts of interest that have resulted in the mismanagement of resources and revenues, corruption, failed strategies and the ultimate failure of the system. Some countries have succeeded in identifying areas for progressive reform, whilst others failed due to various reasons discussed in this thesis. Iraq fits into the category of a country that has failed to implement reform and has become a classic case of a rentier state. -

Interview #25

United States Institute of Peace Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Iraq PRT Experience Project INTERVIEW #25 Interviewed by: Barbara Nielsen Initial Interview May 1, 2008 Copyright 2008 USIP & ADST Executive Summary The interviewee was the PRT team leader in Diyala province from February, 2007 until March, 2008. Diyala province is ethnically mixed, comprised of roughly 20% Shia, 40% Sunni, 9% Kurd, and the remainder other groups. Although intermarriage was frequent (e.g. the governor’s paramount wife was a Shia, but his young wife was a Sunni) and coexistence among the groups had been traditional, after the fall of Saddam Hussein, the sectarian divide was accentuated, along with the manifestation of a complex mosaic of conflicting loyalties and historical grievances. The interviewee’s principal mandate was to develop the capacity of the provincial government to function. However, with the constant combat and frequent ambushes he describes, lasting from February through the late fall of 2007, the PRT’s ability to travel was severely limited. The interviewee describes how, initially, they had to pick up the provincial governor in his own village 20 miles away and bring him to the government center so he could sit in his office. After about three months, the PRT renovated and fortified his office so that he could remain there overnight three to four nights per week. That example led to the assistant governor, deputy governor and other directors resorting to the same governing technique. The interviewee describes how Al-Qaeda was initially invited into the province to protect the Sunni inhabitants from the Shia militia operating at the behest of the Shia police chief. -

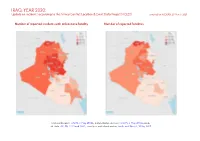

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

IRAQ, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018b; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018a; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Protests 1795 13 36 Conflict incidents by category 2 Explosions / Remote 1761 308 824 Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 2 violence Battles 869 502 1461 Methodology 3 Strategic developments 580 7 11 Conflict incidents per province 4 Riots 441 40 68 Violence against civilians 408 239 315 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5854 1109 2715 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Written Testimony for HB 437 – Marine Sergeant David R Christoff Memorial Highway David Volunteered for Duty the Day After

Written Testimony for HB 437 – Marine Sergeant David R Christoff Memorial Highway David volunteered for duty the day after the September 11, 2001 (9/11) attack on the World Trade Centers in New York City; he was motivated by the desire to protect the freedom and safety of those he loved. On February 22, 2002 he graduated from the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island as a Private First Class. He attended the School of Infantry at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina and was then assigned with the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, Bravo Company at Marine Corps Base Hawaii. David was promoted to Sergeant on October 1, 2004 and on his first deployment he served as Squad Leader in the second Battle of Fallujah code name “Operation Phantom Fury” which is considered to be the bloodiest battle of the Iraq war. After David returned from this deployment in March of 2005, he volunteered to transfer to the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, Kilo Company because he felt there was still much work to be done in Iraq and he wanted to teach the younger Marines the hard lessons he had learned during his previous deployment. He served as Platoon Sergeant starting September 12, 2005 and was deployed to Haqlaniyah, Iraq on March 11, 2006. Upon returning from a foot patrol on May 22, 2006 David was killed by an improvised explosive device. He was laid to rest along with many other fallen heroes at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. During his 5 years he had the opportunity to serve, he made a lifetime of impressions on those he served with, many of whom have relayed stories of his courage, compassion and leadership, attributes he displayed on a daily basis.